Burden of Injury During the Complex Political Emergency in Northern Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buikwe District Economic Profile

BUIKWE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT P.O.BOX 3, LUGAZI District LED Profile A. Map of Buikwe District Showing LLGs N 1 B. Background 1.1 Location and Size Buikwe District lies in the Central region of Uganda, sharing borders with the District of Jinja in the East, Kayunga along river Sezibwa in the North, Mukono in the West, and Buvuma in Lake Victoria. The District Headquarters is in BUIKWE Town, situated along Kampala - Jinja road (11kms off Lugazi). Buikwe Town serves as an Administrative and commercial centre. Other urban centers include Lugazi, Njeru and Nkokonjeru Town Councils. Buikwe District has a total area of about 1209 Square Kilometres of which land area is 1209 square km. 1.2 Historical Background Buikwe District is one of the 28 districts of Uganda that were created under the local Government Act 1 of 1997. By the act of parliament, the district was inniatially one of the Counties of Mukono district but later declared an independent district in July 2009. The current Buikwe district consists of One County which is divided into three constituencies namely Buikwe North, Buikwe South and Buikwe West. It conatins 8 sub counties and 4 Town councils. 1.3 Geographical Features Topography The northern part of the district is flat but the southern region consists of sloping land with great many undulations; 75% of the land is less than 60o in slope. Most of Buikwe District lies on a high plateau (1000-1300) above sea level with some areas along Sezibwa River below 760m above sea level, Southern Buikwe is a raised plateau (1220-2440m) drained by River Sezibwa and River Musamya. -

Priority Service Provision Under Decentralization: a Case Study of Maternal and Child Health Care in Uganda

Small Applied Research No. 10 Priority Service Provision under Decentralization: A Case Study of Maternal and Child Health Care in Uganda December 1999 Prepared by: Frederick Mwesigye, M.A Makerere University Abt Associates Inc. n 4800 Montgomery Lane, Suite 600 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 n Tel: 301/913-0500 n Fax: 301/652-3916 In collaboration with: Development Associates, Inc. n Harvard School of Public Health n Howard University International Affairs Center n University Research Co., LLC Funded by: U.S. Agency for International Development Mission The Partnerships for Health Reform (PHR) Project seeks to improve people’s health in low- and middle-income countries by supporting health sector reforms that ensure equitable access to efficient, sustainable, quality health care services. In partnership with local stakeholders, PHR promotes an integrated approach to health reform and builds capacity in the following key areas: > Better informed and more participatory policy processes in health sector reform; > More equitable and sustainable health financing systems; > Improved incentives within health systems to encourage agents to use and deliver efficient and quality health services; and > Enhanced organization and management of health care systems and institutions to support specific health sector reforms. PHR advances knowledge and methodologies to develop, implement, and monitor health reforms and their impact, and promotes the exchange of information on critical health reform issues. December 1999 Recommended Citation Mwesigye, Frederick. 1999. Priority Service Provision Under Decentralization: A Case Study of Maternal and Child Health Care in Uganda. Small Applied Research Paper No. 10. Bethesda, MD: Partnerships for Health Reform Project, Abt Associates Inc. For additional copies of this report, contact the PHR Resource Center at [email protected] or visit our website at www.phrproject.com. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

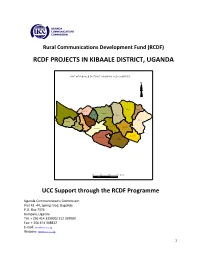

Rcdf Projects in Kibaale District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN KIBAALE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F KIBAAL E DISTRIC T SHO WIN G SUB CO UNTIES N N alwe yo Kisiita R uga sha ri M pee fu Kiry a ng a M aba al e Kakin do Nko ok o Bw ika ra Ky an aiso ke Kag ad i M uho ro Kyeb an do Kasa m by a M uga ra m a Kib aa le TC Bwan s wa Bw am iram ira M atale 10 0 10 20 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..………....……3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….….…..……4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….….………..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Kibaale district………….………..….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Kibaale district………..………………….………...……..….14 10- Map of Kibaale district showing sub counties………..…………………………..….15 11- Table showing the population of Kibaale district by sub counties…………..15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Kibaale district…………………………………….…….……..16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. -

National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures | I

AUGUST 2013 This publication was made possible through the support of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Agency for International Development under contract number GHH-I-00-07-00059-00, AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources (AIDSTAR-One) Project, Sector I, Task Order 1. Uganda National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures | i Acronyms ACP AIDS Control Programme HCW health care waste HCWM health care waste management IP implementing partner MoH Ministry of Health NDA National Drug Authority NEMA National Environmental Management Authority PEPFAR U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief PHC primary health center PMTCT prevention of mother-to-child transmission POP persistent organic pollutants SMC safe male circumcision STI sexually transmitted infections UAC Uganda AIDS Commission UNBOS Uganda National Bureau of Standards USG U.S. Government WHO World Health Organization ii | Uganda National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures Table of Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ............................................................................................................................................................. v 1.0 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................... -

Mobility and Crisis in Gulu Drivers, Dynamics and Challenges of Rural to Urban Mobility

Mobility and crisis in Gulu Drivers, dynamics and challenges of rural to urban mobility SUBMITTED TO THE RESEARCH AND EVIDENCE FACILITY FEBRUARY 2018 Contents Map of Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda 3 Summary 4 1. Introduction 6 Project context and aims of research 6 Significance of the site of investigation 6 Methodology 8 Constraints and limitations 8 2. Research setting and context 9 Socio-cultural context 9 Economic context 10 Rural to urban mobility in historical perspective 13 Impact on urban development 16 3. Migrant experiences 19 Drivers of migration 19 Role of social networks 24 Opportunities and challenges 26 Financial practices of migrants 30 Impact on sites of origin 32 Onward migration 34 4. Conclusion 35 Bibliography 37 This report was written by Ronald Kalyango with contributions from Isabella Amony and Kindi Fred Immanuel. This report was edited by Kate McGuinnes. Cover image: Gulu bus stop, Gulu, Uganda © Ronald Kalyango. This report was commissioned by the Research and Evidence Facility (REF), a research consortium led by the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London and funded by the EU Trust Fund. The Rift Valley Institute works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018. This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Map of Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda FROM CRISIS TO STABILITY? RURAL TO URBAN MOBILITY TO GULU 3 Summary Gulu Municipality is among the fastest growing urban centres in Uganda. In 1991, it was the fourth largest with a population of 38,297. -

Ake ·To ·A Is E I S Ssessme

Lake Victoria fisheries catch assessment survey (CAS) information, Uganda 2005-2007 Item Type monograph Publisher National Fisheries Resources Research Institute Download date 28/09/2021 15:21:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35562 ake · to ·a is e i s ssessme 7 I - . ,_~ ~.. r ~~/.--.J .' . Introduction Management of fisheries resources requires information on the fish stocks; the magnitude, distribution and trends of fishing effort and the trends of fish catches. Catch Assessment SUNeys (CAS) in Lake Victoria are one of the ways through which the partner states sharing the lake are generating the key information required. The EU-funded Project, Implementation of a Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) for Lake Victoria through the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation (LVFO) is supporting the implementation of regionally harmonized CAS in the lake, In the Uganda part of the lake, CAS activities are carried out at 54 fish landing sites in the 11 riparian districts. The National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI), the Department of Fisheries Resources (DFR), and the Districts of Busla, Bugiri, Mayuge, Jinja, Mukono, Wakiso, Kampala, Mpigi, Masaka, Kalangala and Rakai jointly conduct the sUNeys, The CAS enumerators are recruited from the fishing communities and work under direct supeNision of sub-county fisheries officers. I CAS enumerators collecting data Wh"l Catch ASS€SSTn€T\t Surv€"IS? The CAS data are used to estimate Catch per Unit of Effort (CPUE) or Fish catch rates, which, are used together with Fishing Effort information obtained from Frame sUNeys to estimate: 1, The quantities of fish landed in the riparian districts along Lake Victoria; 2, The monetary value of the fish catches; and 3. -

Local Government Councils' Perfomance and Public

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 Lillian Muyomba-Tamale Godber W. Tumushabe Ivan Amanigaruhanga Viola Bwanika-Semyalo Emma Jones 1 ACODE Policy Research Series No. 45, 2011 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFORMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/10 Lillian Muyomba-Tamale Godber W. Tumushabe Ivan Amanigaruhanga Viola Bwanika-Semyalo Emma Jones i LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Muyomba-Tamale, L., (2011). Local Government Councils’ Performance and public Service Delivery in Uganda: Mukono District Council Score-Card Report 2009/10. ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 45, 2011. Kampala. © ACODE 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this general exemption. -

Chapter 10 Natural and Social Environmental Studies

CHAPTER 10 NATURAL AND SOCIAL ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES The Feasibility Study on the Construction of JICA / MOWT / UNRA A New Bridge across River Nile at Jinja Oriental Consultants Co., Ltd. Final Report Eight - Japan Engineering Consultants INC. 10. NATURAL AND SOCIAL ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES 10.1 Natural Environmental Study 10.1.1 General This Chapter summarizes the initial environmental examination (IEE) for the engineering options (i.e., three route alternatives, named Routes A, B and C, respectively), regarding the study on natural environment, and potential environmental issues associated with the implementation of each alternative option. Firstly, the current baseline of the environmental condition surrounding the study site is described. The study area is located between Lake Victoria and the on-going construction site in Bujagali Dam, so that the current local environmental topics, linking both sites, were also studied. Technical site inspections were carried out in November and December 2008 and February and March 2009. Based on the major findings obtained from the technical site inspections and the review of available reports, the baseline environmental information, regarding the natural environment surrounding the study area, was collected. Based on the baseline environmental information and the engineering features of each alternatives, prepared by the study, the IEE was carried out. Basically, the IEE was carried out in two steps. In the first step, a preliminary IEE for two scenarios was carried out: (i) Do - Nothing scenario, and (ii) Do – Project scenario for all prepared route alternatives (i.e., Routes A, B and C); for which preliminary scenarios analysis was conducted. In the second step, a more detailed, route-specific IEE was carried out using more specific engineering information prepared in March 2009, and possible adverse environmental impacts that may occur during and/after the construction of works for each alternative alignment option was summarized. -

Rcdf Projects in Buikwe District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN BUIKWE DISTRICT, UGANDA MA P O F BU IK W E D ISTR IC T S H O W IN G S U B C O U NTIE S N Wakisi Njeru TC Najjem be Lugazi TC N yenga Kawolo Buikw e Najja N kokonjeru TC Ngogwe Ssi-B uk unja 4 0 4 8 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....……3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..……4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…………..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Buikwe district………….……...…….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Buikwe district………..………………….………...…………..14 10- Map of Buikwe district showing sub counties………..………………………………..15 11- Table showing the population of Buikwe district by sub counties…………....15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Buikwe district…………………………………….…………..…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. -

1. Full Title of the Project Feasibility Study on the Construction of a New Bridge Across River Nile at Jinja

1. Full title of the Project Feasibility Study on the Construction of a New Bridge Across River Nile at Jinja 2. Type of the study Preparatory Study 3. Categorization and its reason Category: A Reason: Every proposed new bridge construction route has a resettlement as a result of this preparatory study. Some proposed route has a slightly large-scale resettlement. And the influence on the existing social infrastructures (e.g. power generation and substation facilities, resort hotel, resort center) is also considered. Therefore, category should be set to A. 4. Agency or institution responsible for the implementation of the project The Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) has been inaugurated on July 1, 2008. The competent authority of the government level is MOWT. However, UNRA serves as a counterpart in actual. Organization chart of UNRA is shown in Figure 4-1. Figure 4-1 Organization Chart of UNRA 5. Outline of the Project (1) Objectives The Republic of Uganda is roughly divided into eastern and western part in the country by the Nile River which flows out from the Lake Victoria. Northern corridor, which borders Kenya on the east side of Uganda, passes Kampala the capital of Uganda and is connected with Tanzania and Rwanda in southwest of Uganda. The Northern corridor is a main artery of the traffic in the East Africa whole region and crosses the Nile River near the Jinja district which located about 80km east from the capital Kampala. For Uganda which is a landlocked country, impassable of the Northern corridor is serious problem on transportation of life substances and traffics etc. -

Uganda: Selected Fish Landing Sites and Fishing Communities

Uganda: Selected Fish Landing Sites and Fishing Communities Survey Undertaken by Fisheries Training Institute for the DFID Project Impacts of globalisation on fish utilisation and marketing systems in Uganda Contents Survey Information Landing Sites on Lake Victoria 1. Kasensero, Rakai District 3 2. Kasenyi, Wakiso District 7 3. Katosi, Mukono District 15 4. Kigungu, Wakiso District 20 5. Kyabasimba Rakai District 27 6. Masese, Jinja District 30 7. Ssenyi, Mukono District 34 8. Wairaka, Jinja District 38 Landing Sites on Lake Kyoga 9. Kayago, Lira District 42 10. Kikaraganya, Nakasongola District 45 11. Kikarangenye, Nakasongola District 58 12. Lwampanga, Nakasongola District 61 13. Namasale, Lira District 74 Landing Sites on Lake Albert 14. Abok, Nebbi District 78 15. Dei, Nebbi District 80 16. Kabolwa, Masindi District 84 17. Wanseko, Masindi District 88 Landing Sites on Lakes Edward and George 18. Kasaka, Bushenyi District 93 19. Katunguru, Bushenyi District 98 20. Katwe, Kasese District 99 21. Kayanja, Kasese District 105 The fieldwork was undertaken by former students at the Fisheries Training Institute in July and August 2002. They recorded their observations on the landing sites and conducted a semi-structured discussion with a group of women at each. The topics covered in the discussion are outlined on the next page. Report edited June 2004. FISHERIES GOBALISATION SURVEY PART III: FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION (to be used for case study) Group: To identify women leader and those women specifically dealing in fisheries business at landing sites. 1. Can you narrate the development of fisheries over time (before export boom, when exports had just started and now) in terms of the following.