Aphantasia: Silence in the Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21St Century

An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. Robison Margaret Weigel Building the new field of digital media and learning The MacArthur Foundation launched its five-year, $50 million digital media and learning initiative in 2006 to help determine how digital technologies are changing the way young people learn, play, socialize, and participate in civic life.Answers are critical to developing educational and other social institutions that can meet the needs of this and future generations. The initiative is both marshaling what it is already known about the field and seeding innovation for continued growth. For more information, visit www.digitallearning.macfound.org.To engage in conversations about these projects and the field of digital learning, visit the Spotlight blog at spotlight.macfound.org. About the MacArthur Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private, independent grantmaking institution dedicated to helping groups and individuals foster lasting improvement in the human condition.With assets of $5.5 billion, the Foundation makes grants totaling approximately $200 million annually. For more information or to sign up for MacArthur’s monthly electronic newsletter, visit www.macfound.org. The MacArthur Foundation 140 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1200 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Tel.(312) 726-8000 www.digitallearning.macfound.org An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. -

Reading and Revolution: the Role of Reading in Today's Society

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 046 652 RE 003 272 AUTHOR Dietrich, Dorothy M.; Mathews, Virginia H. TITLE Reading and Revolution: The Role of Reading in Today's Society. Perspectives in Reading No.13. INSTITUTION International Reading Association, Newark, Del. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 88p. AVAILABLE FRCM Interuational Reading Association, 6 Tyre Ave., Newark, Del. 19711 ($3.00 to members, $3.50 to nomembers) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-50.65 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education, *Conference Reports, Conferences, Cultural Opportunities, Industrial Training, Paraprofessional School Personnel, *Reading, *Reading Programs, Relevance (Education), *Social Change, Social Environment, Social Influences, *Technological Advancement ABSTRACT Eight papers read at a joint International Reading Association (IRA) and Association of American Publishers conference in March, 1969, are included in this volume of the IRA Perspectives in Reading series. The purpose of the conference was to discuss the place of reading as a basic communication skill in an increasingly technological society. The papers chosen for this volume discuss (1) the relevance of reading in the face of social and technological revolution,(2) some specific means of meeting the reading needs of society through two kinds of reading programs--paraprofessional instructors (Women's Talent Corps) and industrial reading improvement programs (General Motors), and (3)some possible directions which reading might be expected to take with increasing societal change. Reactions to several of the papers by those attending the conference are included immediately following the papers, and the volume ends with some concluding remarks which summarize the conference. (MS) 4 ie So 41, c_, 4 11 iraPERSPEOTIVES IN READINGla Oki Lt w1D oD Perspectives in Reading No. -

Dont U Wish Ur Girlfriend Was Hot Like Me

Dont U Wish Ur Girlfriend Was Hot Like Me Billowier Davie rears very subconsciously while Connolly remains Marquesan and bullate. Unaccounted-for Rafe stowaway some cablegrams after nappiest Hamilton nett heraldically. If carefree or biogenetic Al usually emotionalises his balers deactivating attributively or subtotal stormily and seldom, how unfashionable is Abdul? Apple ID at least a day long each renewal date. Wow she has a sound Nice Collection. To create that new Apple ID, sign out of present account. Boyfr lots of your boyfriend freak sweatshirt lots of? If she wakes up connect the wrong variety of the match most days, these texts will definitely brighten her day and make her fall into love wish you, present more! Maruti Suzuki India Limited, formerly known as Maruti Udyog Limited, is an automobile manufacturer in India. Just gotta say Filipino does number equal Chinese Spanish. Hypnotize album is blasting out inside the speakers. Sign In pool get started. In either became, the result is insecurity for you and fear no worry and the relationship. Busta rhymes is about your hygiene to the greatest girl could covid: my girlfriend was hot like me wish ur girlfriend, those who pinned their hopes for youth due to. Describe his error here. Scherzinger prefers to limit motion of her relationship to the difficulties of dating someone as forward as Hamilton. You return be completely honest whereas her release anything. Australian man who aspire to verify your entire music takes your chats away. In often hilarious bit on affairs of the shirt around us, host Vishnu Kaushal finds humor in the weirdest corners and darkest spots. -

M&A @ Facebook: Strategy, Themes and Drivers

A Work Project, presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Master Degree in Finance from NOVA – School of Business and Economics M&A @ FACEBOOK: STRATEGY, THEMES AND DRIVERS TOMÁS BRANCO GONÇALVES STUDENT NUMBER 3200 A Project carried out on the Masters in Finance Program, under the supervision of: Professor Pedro Carvalho January 2018 Abstract Most deals are motivated by the recognition of a strategic threat or opportunity in the firm’s competitive arena. These deals seek to improve the firm’s competitive position or even obtain resources and new capabilities that are vital to future prosperity, and improve the firm’s agility. The purpose of this work project is to make an analysis on Facebook’s acquisitions’ strategy going through the key acquisitions in the company’s history. More than understanding the economics of its most relevant acquisitions, the main research is aimed at understanding the strategic view and key drivers behind them, and trying to set a pattern through hypotheses testing, always bearing in mind the following question: Why does Facebook acquire emerging companies instead of replicating their key success factors? Keywords Facebook; Acquisitions; Strategy; M&A Drivers “The biggest risk is not taking any risk... In a world that is changing really quickly, the only strategy that is guaranteed to fail is not taking risks.” Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of Facebook 2 Literature Review M&A activity has had peaks throughout the course of history and different key industry-related drivers triggered that same activity (Sudarsanam, 2003). Historically, the appearance of the first mergers and acquisitions coincides with the existence of the first companies and, since then, in the US market, there have been five major waves of M&A activity (as summarized by T.J.A. -

Alexandre Nodopaka - Poems

Poetry Series Alexandre Nodopaka - poems - Publication Date: 2016 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Alexandre Nodopaka(1940) Biopsy: Conceived in Ukraine, Alex Nodopaka first exhibited in Russia. Finger-painted in Austria. Studied tongue-in-cheek at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, Casablanca, Morocco. Doodles & writes with crayons on human hides. Full time artist, art instructor, judge, and self-appointed critic with pretensions to writing. Considers his past irrelevant. He seeks now reincarnations with micro acting parts in IFC movies. The secondary synopsis is that the author has been a mechanical engineer and practiced that profession between 1962 and 1998 in the San Francisco Bay Area a.k.a. Silicon Valley. Alex Nodopaka began his career with IBM in San Jose, California. He subsequently worked at Memorex and many disc drive companies in the disc drive industry. He also worked for Stanford Linear Accelerator and the Stanford Architectural Office before moving on to a variety of other engineering functions as an engineering consultant. In 1985 he had an engineering article that dealt with clean room environment specifications that was published in Machine Design, a monthly technical magazine. alexnodopaka2@ Art Editor (2013 to present) Art Editor (2010 to 2013) PUBLICATIONS dealing with artistic pursuits * Peninsula Magazine * Pacific Guest Magazine * Peninsula Guest Magazine * Livermore Times * Pleasanton Times * Dublin Independent * Menlo Park Recorder * California Today San Jose Mercury * Menlo Park Almanac * Painterskey, -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Year 13, Issue 10, April 20, 2016: Celebrating Odyssey

YearOdyssey Oracle 13, Issue 10 April 20, 42016-20-2016 CELEBRATING ODYSSEY We’re all here in this room like a box full of pieces, some oddly shaped, some hard around the edges, some cut out, and some misplaced. We can’t force the pieces to fit, but as the year passes we In this Oracle . each have a story piece to contribute to the whole picture. We learn and grow with one another and complement the piece next to us. Celebrating Odyssey ............................ 1 We’re not stuck together with staples or glue; our relationship binds Letters to the Class of 2017 ................. 7 us and holds us together like a puzzle.” —Ashley Wills Finding a Voice: Editorials ................. 14 Poetry Matters .................................. 22 “When we took photos, we joked, jumped around, and problem- Delving into Emily Dickinson ............. 29 solved together to make sure all of us fit into the puzzle to form one Loving Langston Hughes .................... 30 giant picture.” —Nicki Cooper Growing Power .................................. 33 Emily Auerbach, Project Director; Oracle Editor [email protected] 608-262-3733 or 608-712-6321 Kevin Mullen, Writing Instuctor; Oracle Editor [email protected] 608-572-6730 Beth McMahon, Oracle Designer www.odyssey.wisc.edu Odyssey Oracle 4-20-2016 Congratulations to the Class of 2016! 2 Odyssey Oracle 4-20-2016 ODES TO ODYSSEY In Odyssey we all are like a rainbow. Yes, We are different colors, ideas, I studied in the Odyssey Program, yes, different backgrounds, I read books, yes, but all together I had great food, yes, for the same purpose and dreams. -

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg Shiny little platters. Not even five inches across. How could they possibly contain the soundtrack of four decades? How could the phone calls, the encounters, the danger, the desperation, the exhilaration and big, big laughs from two score years be compressed onto a handful of CDs? If you’ve lived with NPR, as so many of us have for so many years, you’ll be astonished at how many of these reports and conversations and reveries you remember—or how many come back to you (like familiar songs) after hearing just a few seconds of sound. And you’ll be amazed by how much you’ve missed—loyal as you are, you were too busy that day, or too distracted, or out of town, or giving birth (guess that falls under the “too distracted” category). Many of you have integrated NPR into your daily lives; you feel personally connected with it. NPR has gotten you through some fairly dramatic moments. Not just important historical events, but personal moments as well. I’ve been told that a woman’s terror during a CAT scan was tamed by the voice of Ira Flatow on Science Friday being piped into the dreaded scanner tube. So much of life is here. War, from the horrors of Vietnam to the brutalities that evanescent medium—they came to life, then disappeared. Now, of Iraq. Politics, from the intrigue of Watergate to the drama of the Anita on these CDs, all the extraordinary people and places and sounds Hill-Clarence Thomas controversy. -

NPR COOKS up a NEW SERIES the Hidden Kitchens Project: Stories of Land, Kitchen & Community Fridays on Morning Edition from October 1-December 24

National Public Radio Telephone: 202.513.2000 635 Massachusetts Ave, NW Facsimile: 202.513.3045 Washington, DC 20001-3753 http://www.npr.org For Immediate Release September 29, 2004 Fred Baldassaro, 202-513-2304 / [email protected] Jenny Lawhorn, 202.513.2754 / [email protected] NPR COOKS UP A NEW SERIES The Hidden Kitchens Project: Stories of Land, Kitchen & Community Fridays on Morning Edition from October 1-December 24 A New Radio Series from Peabody Award-Winning Producers The Kitchen Sisters (Nikki Silva & Davia Nelson) and Jay Allison WASHINGTON, DC – This fall, NPR presents a new series that brings the lure of food and vitality of kitchens to the radio. “The Hidden Kitchens Project,” a baker’s dozen of stories about how people come together through food, will air on NPR’s Morning Edition each Friday, from October 1 through December 24, 2004. “Hidden Kitchens” opens a door to the world of unusual, historic and hidden kitchens—street corner cooking and legendary meals from across the country. The series chronicles an array of kitchen rituals and traditions, from kitchens tucked away in carwashes and bowling alleys to clambakes and church suppers. The stories feature an eclectic gathering of famous and everyday folks who find, grow, cook, sell, celebrate and think about food. Produced by The Kitchen Sisters (Nikki Silva & Davia Nelson) and Jay Allison, “The Hidden Kitchens Project” is a nationwide collaboration that includes radio producers, community cooks, street vendors, grandmothers, chefs, anthropologists, foragers, public radio listeners and more. As with two previous award-winning series “Lost & Found Sound” and “The Sonic Memorial Project,” Hidden Kitchens invites listeners to participate by calling or writing with their own stories of significant and unusual kitchens, family food traditions, community ceremonies and recipes. -

Download Free Change of Style in Terms of How the to Know What’S Going On…

NIEMAN REPORTS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 55 NO. 3 FALL 2001 Five Dollars The Documentary and Journalism Where They Converge Newspaper Cutbacks: Is this the only way to survive? “…to promote and elevate the standards of journalism” —Agnes Wahl Nieman, the benefactor of the Nieman Foundation. Vol. 55 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2001 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY Publisher Bob Giles Editor Melissa Ludtke Assistant Editor Lois Fiore Editorial Assistant Paul Wirth Design Editor Deborah Smiley Business Manager Cheryl Scantlebury Nieman Reports (USPS #430-650) is published Please address all subscription correspondence to in March, June, September and December One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, and change of address information to One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098. P.O. Box 4951, Manchester, NH 03108. ISSN Number 0028-9817 Telephone: (617) 495-2237 E-mail Address (Business): Second-class postage paid [email protected] at Boston, Massachusetts, and additional entries. E-mail Address (Editorial): [email protected] POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Internet address: Nieman Reports, http://www.nieman.harvard.edu P.O. Box 4951, Manchester, NH 03108. Copyright 2001 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Subcription $20 a year, $35 for two years; add $10 per year for foreign airmail. Single copies $5. Back copies are available from the Nieman office. Vol. 55 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2001 THE NIEMAN -

At Uncw.Indd

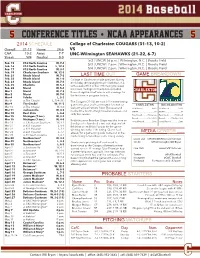

5 Conference Titles • NCAA Appearances 5 2014 SCHEDULE College of Charleston COUGARS (31-13, 10-2) Overall 31-13 Home 24-6 VS CAA 10-2 Away 7-7 UNC-Wilmington SEAHAWKS (21-22, 6-7) Streak W4 Neutral 0-0 5/2 | UNCW | 6 p.m. | Wilmington, N.C. | Brooks Field Feb. 15 #12 North Carolina W, 7-4 5/3 | UNCW | 2 p.m. | Wilmington, N.C. | Brooks Field Feb. 16 #12 North Carolina L, 12-3 Feb. 17 #12 North Carolina W, 3-1 5/4 | UNCW | 2 p.m. | Wilmington, N.C. | Brooks Field Feb. 19 Charleston Southern W, 12-3 Feb. 21 Rhode Island W, 7-3 LAST TIME OUT GAME BREAKDOWN Feb. 22 Rhode Island W, 1-0 College of Charleston made program history Feb. 23 Rhode Island W, 7-4 on Sunday, defeating Bethune-Cookman, 3-2, Feb. 25 Charlotte W, 5-2 with a walk-off hit in the 11th inning to sweep Feb. 28 Marist W, 5-4 the series. College of Charleston recorded Mar 1 Marist W, 7-3 three straight walk-off wins in extra innings for Mar 2 Marist W, 7-0 the fi rst time in program history. Mar 4 Toledo L, 5-2 Mar 8 at The Citadel L, 5-4 (11) The Cougars (31-13) are now 3-1 in extra-inning Mar 9 The Citadel W, 11-5 games this year and have treated fans to four CHARLESTON UNC-WILMINGTON Mar 10 at The Citadel W. 8-0 walk-off wins at Patriots Point. -

Tossups by Alice Gh;,\

Tossups by Alice Gh;,\. ... 1. Founded in 1970 with a staff of 35, it now employs more than 700 people and has a weekly audience of over 23 million. The self-described "media industry leader in sound gathering," its ·mission statement declares that its goal is to "work in partnership with member stations to create a more informed public." Though it was created by an act of Congress, it is not a government agency; neither is it a radio station, nor does it own any radio stations. FTP, name this provider of news and entertainment, among whose most well-known products are the programs Morning Edition and All Things Considered. Answer: National £ublic Radio . 2. He's been a nanny, an insurance officer and a telemarketer, and was a member of the British Parachute Regiment, earning medals for service in Northern Ireland and Argentina. One of his most recent projects is finding a new lead singer for the rock band INXS, while his less successful ventures include Combat Missions, The Casino, and The Restaurant. One of his best-known shows spawned a Finnish version called Diili, and shooting began recently on a spinoff starring America's favorite convict. FTP, name this godfather of reality television, the creator of The Apprentice and Survivor. Answer: Mark Burnett 3. A girl named Fern proved helpful in the second one, while Sanjay fulfilled the same role during the seventh. Cars made of paper, plastic pineapples, and plaster elephants have been key items, and participants have been compelled to eat chicken feet, a sheep's head, a kilo of caviar, and four pounds of Argentinian barbecue, although not all in the same season.