US Funds to Two Micronesian Nations Had Little Impact on Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mangroves Occurring on the Many Islands in the South Pacific Are Only a Small Component When Compared to the Worldwide Inventory of Mangroves

TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT AND SUPPORT FOR MANGROVE AND LITTORAL FOREST MANAGEMENT, PLANNING AND TRAINING FOR SMALL ISLANDS IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC Jan. 25, 2004 by James Denny Ward USDA Forest Service i FOREWORD Mangroves occurring on the many islands in the South Pacific are only a small component when compared to the worldwide inventory of mangroves. Although the mangroves found on the smaller islands may not seem as important on the global scale, they are extremely important to the small individual countries. Some of their benefits include shoreline protection, biodiversity, fisheries and a source for traditional products like building material, fuelwood and various cultural uses. These benefits are even more important to small island countries with limited resources and contributed to the survival of the indigenous people in earlier times. Realizing the importance of the mangrove resource the Forest & Trees Support Programme of SPC and the Heads of Forestry in the Pacific in cooperation with the USDA Forest Service conducted several missions during the last 10 years to assist the smaller island countries with preserving, protecting and managing their mangroves . The USDA Forest Service’s Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry based in Hawaii has been providing assistance to the Federated States of Micronesia and other islands with close ties to the United States for several years. Research conducted by this group has contributed greatly to the information base needed to manage mangroves throughout the South Pacific. This report is not all-inclusive but it is hoped that it will contain sufficient information to assist small islands in developing a management strategy for their individual countries. -

View Annual Report

2017 ANNUAL REPORT NAVIGATING TOMORROW CONTENTS 1 Chairman’s Message 3 2017 Financial Summary 4 Year in Review 8 Our Community 12 Our Employees 14 Client Profiles 22 2017 Financial Report 24 Relative Stock Prices 25 Bank of Hawaii Locations 26 Managing Committee 28 Board of Directors 29 Shareholder Information NaVIGATING TOMORROW The story of Bank of Hawaii began on Dec. 27, 1897, when Bank of Hawaii became the first chartered and incorporated bank to do business in the Republic of Hawaii. For more than 120 years, we have been helping generations of families, individuals, community organizations and businesses achieve their dreams. The cover image was taken at Bank of Hawaii’s Main Branch grand re-opening in August 2017, when a new Branch of Tomorrow concept was unveiled for its flagship location in downtown Honolulu. Designed with modern technology, digital conveniences and private spaces for personal interactions, the branch features elements of the Hawaiian voyaging canoe, which has always had special meaning for Bank of Hawaii. The Bank of Hawaii canoe, Ulu o ka lā, was commissioned in 2015 and continues to serve as a symbol for the bank. The unique circular overlay pays tribute to the original iron gate at Main Branch. Bank of Hawaii marked 120 years of doing business in 2017, and continues to help its customers explore new possibilities and navigate toward their financial and life goals. View Bank of Hawaii’s 2017 digital summary annual report, featuring videos of our ©2017, Bank of Hawaii Corporation. Bank of Hawaii®, Bankoh® and the Bank of Hawaii logo are Chairman, clients, registered trademarks of Bank of Hawaii. -

Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008 OCHA Presence in the Pacific Northern Papua New Guinea Fiji Mariana Humanitarian Affairs Unit (HAU), PNG Regional Disaster Response Islands (U.S.) UN House , Level 14, DeloitteTower, Advisor (RDRA), Fiji Douglas Street, PO Box 1041, 360 Victoria Parade, 3rd Floor Fiji +10 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Development Bank Building, Suva, FIJI Tel: +675 321 2877 Tel: +679 331 6760, +679 331 6761 International Date Line Fax: +675 321 1224 Fax: +679 330 9762 Saipan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Head: Vini Talai Head: Peter Muller Agana +12 Guam (U.S.) Pacific Ocean +10 MARSHALL ISLANDS Legend Depth (m) OCHA Presence Below 5,000 1,001 to 2,000 MICRONESIA (FSO) Koror Majuro Country capital Palikir 4,001 to 5,000 501 to 1,000 Territory capital PALAU +11 Illustrative boundary 3,001 to 4,000 101 to 500 +9 +10 Time difference with UTC 2,001 to 3,000 o to 100 Tarawa (New York: UTC -5 Equator NAURU Geneva: UTC +1) IMPORTANT NOTE: The boundaries on this map are for illustrative purposes only Yaren Naming Convention and were derived from the map ’The +12 +12 KIRIBATI UN MEMBER STATE Pacific Islands’ published in 2004 by the Territory or Associated State Secretariat of the Pacific Community. INDONESIA TUVALU -11 -10 PAPUA NEW GUINEA United Nations Office for the Coordination +10 +12 of Humanitarian affairs (OCHA) Funafuti Toke lau (N.Z.) Regional Office for Asia Pacific (ROAP) Honiara Executive Suite, 2nd Floor, -10 UNCC Building, -

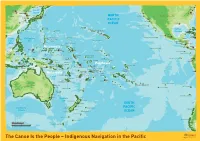

Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific

Hokkaido Vladivostok New York Philadelphia Beijing North Korea Sea of Tianjin Japan P'yongyang Sacramento Washington Seoul Japan Honshu NORTH San Francisco United States of America China South Tokyo Nagoya Korea Pusan Osaka Los Angeles PACIFIC Cheju-Do Shikoku San Diego Shanghai Kyushu OCEAN New Orleans Guadalupe Island (Mex.) Midway Baja Ryukyu Ogasawara- Islands (US) California Trench Okinawa-Jima (Jap.) Gunto (Jap.) Gulf of Miami Minami-Tori- Hawaiian Islands (US) Shima (Jap.) Mexico Havana Taiwan Kauai Cuba Oahu Mexico Hainan Dao Honolulu Guadalajara Jamaica Mariana Mexico Northern Wake Island (US) Hawaii Revillagigedo Island (Mex.) Kingston Philippine Ridge Belize South Luzon Mariana Islands Johnston Atoll (US) China Sea (US) Guatemala Honduras Manila Saipan Sea Guam (US) Marshall Islands El Salvador Nicaragua Philippines Enewetak Managua Costa Rica Panama Yap Islands Micronesia San José Palawan Ratak Clipperton Island (Fr.) Mindanao Pohnpei Chain Davao Melekeok Satawai Panama Chuuk Palikir Majuro Palmyra Atoll (US) Ralik Cocos Islands (CR) Brunei Palau Kosrae Chain Malaysia Line Malpelo Island (Col.) Federated States of Micronesia Gilbert Islands Howland Island (US) Islands Colombia Halmahera Kalimantan Tarawa Baker Island (US) Bismarck Archipelago Quito Jarvis Island (US) Galapagos Islands (Ec.) Sulawesi New Ireland Nauru Guayaquil Phoenix Islands Kiribati Malden Rabaul Ecuador Seram New Guinea Papua Bougainville Solomon Nanumea Vaiaku Indonesia New Guinea New Britain Santa Isabel Islands Polynesia Surabaya Funafuti Marquesas Islands -

Kōkua Creating Good

CONNECTED THROUGH KŌKUA CREATING GOOD. BUILDING STRONGER COMMUNITIES. BANK OF HAWAII COMMUNITY REPORT 2018 workplace where all of our employees feel With nearly half of Hawaii’s people they belong and are able to reach their struggling to get by, the problems full potential to authentically connect outlined in the ALICE report are complex. to the community we serve. Bank of But they’re not insurmountable if we Hawaii has outwardly demonstrated its combine forces to address the issues. support for our LGBTQ community as a One of the most important things for us sponsor of the Honolulu Rainbow Film to do is to realize that the well-being of Festival, and for the first time in 2018, ALICE community members is, in fact, the Honolulu Pride Parade & Festival. our own well-being. We are all connected. I was so proud to march in solidarity Whether we participate from the business, with more than 300 of our employees legislative or philanthropic sectors, we Aloha, and their friends and family alongside each have a vested interest in finding our Bank of Hawaii float in the solutions and ensuring the continued Helping people access a better life Honolulu Pride Parade in October. health of our community. is what Bank of Hawaii does both in a A number of natural disasters in Bank of Hawaii has been helping the professional capacity, and as a caring 2018—volcanic eruptions, typhoons community for over 120 years, and collaborative partner in the community. and tropical storms—brought increased we invite others to partner with our We invest in the innovative vision of challenges to our community, and an efforts. -

Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia

FRAME B 155°E 160°E Rorovana ! ! ! Torokina Panguna Karakun Koiaris ! ! Papua New Guin! ea Taki ! ! Jaba Sininai ! Pupuku PACIFIC OCEAN Aitara ! ! ! Kaekui Mission ! Birambira ! Tokuaka Susuka !Kombokisa !! Kutakana Lukuvaru Shortland Island PACIFIC OCEAN ! ! Ghaomai Choiseul Zambanarungga Shortland I ! ! Vure ! Trevanion Noka ! ! Mono I Matamotu ! ! ! Masoko Java Malemgeulu ! ! Paraso ! Zuzuao Santa Cruz Islands Apakhö ! ! ! Point Lunga ! Eleoteve Arambu Filuo Vana!! ! ! Litoghahira Sambora Santa Isabel Island FRAME D Kolomb!angara! Ganongga ! New Georgia Islands ! Tapurai Tuarugu ! Biluro ! ! Mburuku Loalonga ! Lokiha ! ! ! Sepi ! Ageraba Harai Mbareho ! Fokinkorra ! S o l o m o n I s l a n d s Auki Kunura ! ! Kwaimbaambaala ! Vura Nggaulai'ato'o ! ! ! Siota !! Manikiriu Tulagi Paunairo Vatupilei ! ! Palikir Abungari !. Koror !. Marshall Islands Malaita Palau Guranja Honiara Micronesia Hularu ! ! .! !Gembua ! Guadalcanal Rere ! Kiribati ! ! PACIFIC OCEAN Solomon Sea Mbaole ! Sitaronda Ahenawai Anoni'usu Nauru Ralavu Raurembo ! Mwarada ! ! ! Ione ! Lakatana ! Ahia I n d o n e s i a Makina 10°S Papua New 10°S Guinea Solomon Sea Honiara Heuru !. Port Moresby !. ! Etamarorai Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia !.Port-Vila ! San Cristobal Australia Vinegau ! New Caledonia Na Wosi ! Funakumwa ! ! !. Hauraha Nouméa FRAME A Napasiwai FRAME C 155°E 160°E Date Created: 04- JUL - 2011 Map Num: LogCluster_SLB_LCA_004 Kilometers .! National Capital Road Network National Boundary Coord.System/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 S O L O M O N GLIDE Num: ! Village (selection) Secondary Surface Waterbody The boundaries and names and the designations 0 50 100 150 200 used on this map do not imply official endorsement I S L A N D S FRAME A Nominal Scale 1:62,420,000 at A4 Tertiary or acceptance by the United Nations. -

The Value of Service SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT 2005 BANK of HAWAII CORPORATION and SUBSIDIARIES

the value of service SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT 2005 BANK OF HAWAII CORPORATION AND SUBSIDIARIES FINANCIAL SUMMARY (DOLLARS IN THOUSANDS EXCEPT PER SHARE AMOUNTS) FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31 2005 2004 EARNINGS HIGHLIGHTS AND PERFORMANCE RATIOS Net Income $ 181,561 $ 173,339 Basic Earnings Per Share 3.50 3.26 Diluted Earnings Per Share 3.41 3.08 Dividends Declared Per Share 1.36 1.23 Net Income to Average Total Assets (ROA) 1.81% 1.78% Net Income to Average Shareholders’ Equity (ROE) 24.83% 22.78% Net Interest Margin1 4.37% 4.32% Efficiency Ratio2 53.15% 56.14% AS OF DECEMBER 31 STATEMENT OF CONDITION HIGHLIGHTS AND PERFORMANCE RATIOS Total Assets $ 10,187,038 $ 9,766,191 Net Loans 6,077,446 5,880,134 Total Deposits 7,907,468 7,564,667 Total Shareholders’ Equity 693,352 814,834 Book Value Per Common Share $ 13.52 $ 14.83 Allowance / Loans and Leases Outstanding 1.48% 1.78% Employees (FTE) 2,585 2,623 Branches and Offices 85 87 Market Price Per Share of Common Stock for the Year Ended December 31: Closing $ 51.54 $ 50.74 High $ 54.44 $ 51.10 Low $ 43.82 $ 40.97 FOR THE QUARTER ENDED DECEMBER 31 EARNINGS HIGHLIGHTS AND PERFORMANCE RATIOS Net Income $ 44,781 $ 46,241 Basic Earnings Per Share 0.88 0.86 Diluted Earnings Per Share 0.86 0.82 Net Income to Average Total Assets (ROA) 1.76% 1.89% Net Income to Average Shareholders’ Equity (ROE) 25.19% 23.63% Net Interest Margin1 4.42% 4.40% Efficiency Ratio2 53.92% 55.37% 1 The net interest margin is defined as net interest income, on a fully-taxable equivalent basis, as a percentage of average earning assets. -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): September 4, 2020 FIRST HAWAIIAN, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation) 001-14585 99-0156159 (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) 999 Bishop St., 29th Floor Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) (808) 525-7000 (Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code) Not Applicable (Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last Report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class: Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered: Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share FHB NASDAQ Global Select Market Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

Bank of Hawaii RSSD # 795968

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE August 8, 2016 COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION Bank of Hawaii RSSD # 795968 130 Merchant Street Honolulu, Hawaii, 96813 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 101 Market Street San Francisco, California 94105 NOTE: This document is an evaluation of this institution’s record of meeting the credit needs of its entire community, including low‐ and moderate‐income neighborhoods, consistent with the safe and sound operation of the institution. This evaluation is not, nor should it be construed as, an assessment of the financial condition of this institution. The rating assigned to this institution does not represent an analysis, conclusion or opinion of the federal financial supervisory agency concerning the safety and soundness of this financial institution. Bank of Hawaii CRA Public Evaluation Honolulu, Hawaii August 8, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTITUTION RATING ................................................................................................ 1 Institution’s CRA Rating ....................................................................................................... 1 INSTITUTION ........................................................................................................... 2 Description of Institution ..................................................................................................... 2 Scope of Examination .......................................................................................................... 3 CONCLUSIONS WITH RESPECT TO PERFORMANCE TESTS -

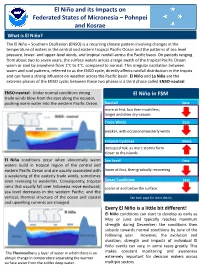

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

A Failed Relationship: Micronesia and the United States of America Eddie Iosinto Yeichy*

A Failed Relationship: Micronesia and the United States of America Eddie Iosinto Yeichy* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 172 II. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MIRCORONESIA AND THE UNITED STATES .............................................................................................. 175 A. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands ........................................ 175 B. Compact of Free Association.................................................... 177 III. UNITED STATES FAILURE TO FULFILL ITS LEGAL DUTIES .................. 178 A. Historical Failures ................................................................... 178 B. Modern Failures ....................................................................... 184 C. Proposed Truths for United States Failure ............................... 186 IV. PROPOSED SOLUTION: SOCIAL HEALING THROUGH JUSTICE FRAMEWORK .................................................................................... 186 A. Earlier Efforts of Reparation: Courts Tort Law Monetary Model ........................................................................................ 187 B. Professor Yamamoto’s Social Healing Through Justice Framework ............................................................................... 188 C. Application: Social Healing Through Justice Framework ....... 191 D. Clarifying COFA Legal Status .................................................. 193 V. CONCLUSION ................................................................................... -

Jesuitvolunteers.Org CHUUK, MICRONESIA Volunteer

CHUUK, MICRONESIA MAU PIAILUG HOUSE JV Presence in Microneisa since 1985 Mailing Address Jesuit Volunteers [JV’s Name] Xavier High School PO Box 220 Chuuk, FSM 96942 Ph: 011-691-330-4266 Volunteer Accompaniment JVC Coordinator Emily Ferron (FJV Chuuk, 2010-12) [email protected] Local Formation Team Fr. Tom Benz, SJ Fr. Dennis Baker, SJ In-Country Coordinator Support Person [email protected] [email protected] Overview The term Micronesia is short for the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), and refers more accurately to geographic/cultural region (not dissimilar to terms such as Central America or the Caribbean). Micronesia contains four main countries (and a few little ones but we’ll focus on the main four): Republic of the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of Palau, and Republic of Kiribati. Within Micronesia, there are many different cultural groups. For instance in FSM, there are four states, each uniquely different (culturally). Within one of those states, one can find different cultural groups as well (outer islands vs lagoon or main island). In some placements JVs have the opportunity to interact with many of these different culture groups from outside of the host island. For example, Xavier High School (in Chuuk), the student and staff/teacher population is truly international and representative of many of these cultural groups. The FSM consists of some 600 islands grouped into four states: Kosrae, Pohnpei, Chuuk (Truk) and Yap. Occupying a very small total land mass, it is scattered over an ocean expanse five times the size of France. With a population of 110,000, each cultural group has its own language, with English as the common language.