Battle Name: Auldearn Council Area: Highland Date: 9Th May 1645 UKFOC Number: 343 NGR: NH 916 554

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karen Helm (March 4, 2006) Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar June Hanley (March 29, 2008)

Tunes Played at Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania Meetings The Battle of Auldearn (Setting #1) Karen Helm (March 4, 2006) Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar June Hanley (March 29, 2008) The Battle of the Pass of Crieff Dan Lyden (April 14, 2018) Beloved Scotland Adam Green (June 18, 2006) Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) – Urlar The Big Spree Thompson McConnell (January 13, 2018) Cabar Feidh Gu Brath Michael Philbin (March 29, 2008) Thompson McConnell (April 14, 2018) Catherine’s Lament Rory McConnell (December 2, 2018) The Cave of Gold Thompson McConnell (November 3, 2007) Thompson McConnell (March 29, 2008) Thompson McConnell (November 30, 2008) Thompson McConnell (March 6, 2010) Thompson McConnell (February 24, 2018) Chisholm’s Salute Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar Ceol Na Mara (Song of the Sea) Laura Neville (March 4, 2018) Clan Campbell’s Gathering Daniel Emery (December 2, 2006) Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) Karen Helm (December 1, 2007) Karen Helm (February 23, 2008) Ken Campbell (March 4, 2018) Daniel Emery (April 8, 2018) The Clan MacNab’s Salute David Bailiff (December 1, 2007) Colin MacRae of Invereenat’s Lament Ken Campbell (January 21, 2006) – Urlar & Variations I & II Marty McKeon (November 3, 2007) Tom Miller (November 30, 2008) Gustav Person (January 13, 2018) Gustav Person (March 4, 2018) The Company’s Lament Patrick Regan (December 2, 2006) Corrienessan’s Salute Tom Miller (January 3, 2009) – Urlar Matt Davis (April 14, 2018) Rory McConnell (December 2, 2018) Cronan Corrievrechan -

Download History of the Mackenzies

History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie [This book was digitized by William James Mackenzie, III, of Montgomery County, Maryland, USA in 1999 - 2000. I would appreciate notice of any corrections needed. This is the edited version that should have most of the typos fixed. May 2003. [email protected]] The book author writes about himself in the SLIOCHD ALASTAIR CHAIM section. I have tried to keep everything intact. I have made some small changes to apparent typographical errors. I have left out the occasional accent that is used on some Scottish names. For instance, "Mor" has an accent over the "o." A capital L preceding a number, denotes the British monetary pound sign. [Footnotes are in square brackets, book titles and italized words in quotes.] Edited and reformatted by Brett Fishburne [email protected] page 1 / 876 HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. NEW, REVISED, AND EXTENDED EDITION. BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, M.J.I., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CHISOLMS;" "THE PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER;" "THE HISTORICAL "TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" "THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE;" ETC., ETC. LUCEO NON URO INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCXCIV. PREFACE. page 2 / 876 -:0:- THE ORIGINAL EDITION of this work appeared in 1879, fifteen years ago. It was well received by the press, by the clan, and by all interested in the history of the Highlands. -

Gazetteer of Selected Scottish Battlefields

Scotland’s Historic Fields of Conflict Gazetteer: page 1 GAZETTEER OF SELECTED SCOTTISH BATTLEFIELDS LIST OF CONTENTS ABERDEEN II ............................................................................................................. 4 ALFORD ...................................................................................................................... 9 ANCRUM MOOR...................................................................................................... 19 AULDEARN .............................................................................................................. 26 BANNOCKBURN ..................................................................................................... 34 BOTHWELL BRIDGE .............................................................................................. 59 BRUNANBURH ........................................................................................................ 64 DRUMCLOG ............................................................................................................. 66 DUNBAR II................................................................................................................ 71 DUPPLIN MOOR ...................................................................................................... 79 FALKIRK I ................................................................................................................ 87 FALKIRK II .............................................................................................................. -

9.4 What Is the Contribution of Hobbyist Metal Detecting To

Ferguson, Natasha (2013) An assessment of the positive contribution and negative impact of hobbyist metal detecting to sites of conflict in the UK. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4370/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] An assessment of the positive contribution and negative impact of hobbyist metal detecting to sites of conflict in the UK Natasha Ferguson, MA (Hons), MA, FSA Scot Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow 2 Abstract In the UK sites of conflict, in particular battlefields, are becoming more frequently associated with the label ‘heritage at risk’. As the concept of battlefield and conflict archaeology has evolved, so too has the recognition that battlefields are dynamic, yet fragile, archaeological landscapes in need of protection. The tangible evidence of battle is primarily identified by distributions of artefacts held within the topsoil, such as lead projectiles, weapon fragments or buttons torn from clothing; debris strewn in the heat of battle. -

Battle of Auldearn Designation Record and Full Report Contents

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Auldearn The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and Potential -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Auldearn Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Auldearn The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record Contents Name Date of Addition to Inventory Alternative Name(s) Date of Last Update Date of Battle Overview and Statement of Local Authority Significance NGR Centred Inventory Boundary Inventory of Historic Battlefields ALFORD Alternative Names: None 2 July 1645 Local Authority: Aberdeenshire NGR centred: NJ 567 162 Date of Addition to Inventory: 21 March 2011 Date of last update: 14 December 2012 Overview and Statement of Significance The Battle of Alford is significant as one of Montrose’s most notable victories in his campaign within Scotland on behalf of Charles I. -

A History of the Scottish Highlands

UViaryAnn & tiriecke (Decorati]/ecArt QoCleEtioru STIRLING AND FRAN CINE CLARJC ART INSTITUTE LIBRART 70H1I EE.SEIHE, EAEL OF MJLRR. :. ,v Edinburgh. GRANT. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library http://archive.org/details/historyofscottis002kelt ! mm i IB I i ;!! i !! ill lljii !! - n h amn III! III! 1 11 111 iiil j.j j III! iiiii i iiiii ROBERTSON. WILLIAM DITKK 0? CUMBERLAJTD :; '' A.t -u.il art m .v C° Londnn - - MENZIES, MOVEMENTS OF MONTEOSE AND BAILLIE. 209 as to prevent him from again taking the field. Montrose had advanced as far as Loch Kat- He therefore left Perth during the night of the rine, when a messenger brought him intelli- 7th of April, with his whole army, consisting gence that General Hurry was hi the Enzie of 2,000 foot and 500 horse, with the inten- with a considerable force, that he had been tion of falling upon Montrose by break of day, joined by some of the Moray-men, and, after before he should be aware of his presence ; but plundering and laying waste the country, was Montrose's experience had taught him the ne- preparing to attack Lord Gordon, who had not cessity of being always upon his guard when a sufficient force to oppose him. On receiving so near an enemy's camp, and, accordingly, he this information, Montrose resolved to proceed had drawn up his army, in anticipation of immediately to the north to save the Gordons Baillie's advance, in such order as would en- from the destruction which appeared to hang able hini either to give battle or retreat. -

The Covenanters in Moray and Ross

LIBRARY OF PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY BX9081 .M31 1875 Covenanters in Moray and Ross Murdoch Macdonald. Srom i^t feifirarg of (pxofcBBox n5?ifftant ^enrg (B>reen 5$equeaf^eb fij? ^im fo t^e fei6rari? of (princefon C^eofogtcaf ^eminarg THE COVENANTERS MORAY AND ROSS: BY REV. MURDOCH MACDONALD, NAIRN. NAIRN: J . T . M E L V E N . EDINBURGH: MACLAREN & MACNIVEN. ELGIN : J. S. FERRIER. FORRES I R. STEWART & SON. : A. &: R. MILNE. INVERNESS : JAMES MELVEN. ABERDEEN 1875. THE PATRON, JOHN ARCHIBALD DUNBAR DUNBAR, Esq., TOUNGER OF SEAPARK, THE DIRECTORS, AND MEMBERS FORRES MECHANICS' INSTITUTE AND LIBRARY, THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. PREFACE The following chapters originated in a series of popular Lectures prepared at the request of the Mechanics' Institute of Forres, and delivered in that town, and in Nairn, Inverness, Invergordon, and Elgin. There was no intention of giving them, either a wider pub- licity, or a more permanent form; but the audiences in the several places having expressed a wish to see my manuscript in print—probably because they felt that the ear required the aid of the eye in following the details of the narrative, — it is now published. The sketch has grown somewhat in the reproduction, but the demands of a laborious pastorate have for- bidden any attempt to recast it in a more strictly his- toric form, or to bestow upon it a treatment worthier of the subject. Whatever its imperfections, I trust that, at the least, the men of Moray and Eoss Avill recognise it as a well-meaning, if feeble, attempt to keep alive the memory of men and of deeds that ought not to be forgotten by us. -

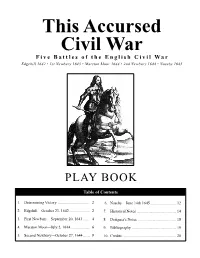

TACW Playbook-3

This Accursed Civil War 1 This Accursed Civil War Five Battles of the English Civil War Edgehill 1642 • 1st Newbury 1643 • Marston Moor 1644 • 2nd Newbury 1644 • Naseby 1645 PLAY BOOK Table of Contents 1. Determining Victory ................................. 2 6. Naseby—June 14th 1645 .......................... 12 2. Edgehill—October 23, 1642 ..................... 2 7. Historical Notes ........................................ 14 3. First Newbury—September 20, 1643 ....... 4 8. Designer's Notes ....................................... 18 4. Marston Moor—July 2, 1644.................... 6 9. Bibliography ............................................. 19 5. Second Newbury—October 27, 1644 ....... 8 10. Credits ....................................................... 20 © 2002 GMT Games 2 This Accursed Civil War Determining Victory Parliament. The King had a clear advantage in numbers and quality of horse. The reverse was the case for Parliament. This Royalists earn VPs for Parliament losses and vice versa. Vic- pattern would continue for some time. tory is determined by subtracting the Royalist VP total from the Parliament VP total. The Victory Points (VPs) are calculated Prelude for the following items: Charles I had raised his standard in Nottingham on August 22nd. Victory The King found his support in the North, Wales and Cornwall; Event Points the Parliament in the South and East. The army of Parliament Eliminated Cavalry Unit ............................................. 10 was at Northampton. The King struck out towards Shrewsbury to gain needed support. Essex moved on Worcester, trying to Per Cavalry Casualty Point place his army between the King and London, as the King's on Map at End ............................................................. 2 army grew at Shrewsbury. By the 12th of October the King felt Eliminated Two-Hex Infantry Unit ............................. 10 he was sufficiently strong to move on London and crush the Eliminated One-Hex Heavy Infantry Unit ................. -

Clan History from Scotweb

Robertson Clan Donnachaidh, sometimes known as Clan Robertson, is a Scottish clan. William Forbes Skene (1809-92), Historiographer Royal of Scotland, wrote in 1837 that: “the Robertsons of Struan are unquestionably the oldest family in Scotland, being the sole remaining branch of that Royal House of Atholl which occupied the throne of Scotland during the 11th and 12th centuries.” Gaelic forms of the name Mac Dhònnchaidh (’son of Duncan’). Mac Raibeirt (’son of Robert’). Origins of the clan The Gaelic Clann Dhònnchaidh claims descent from Duncan I (ruled 1034–1040), King of Scots. He ruled Scotland from 1034, having succeeded his maternal grandfather, Máel Coluim II (1005-43), until killed by Macbeth, Mórmáer of Moray (ruled 1040-57). Duncan may have married Sybil, a daughter (or sister) of Siward, Earl of Northumbria (d. 1055). His consort is also recorded as Suthen, a Gaelic name. Whatever her origins, she had three known children by Duncan. These three sons were Máel Coluim (later Máel Coluim III Ceann Mór, ‘Great Chief’; usually anglicised Malcolm Canmore), Domnall Bán (’Fair-Haired’), later Domnall III), and perhaps Máel Muire of Atholl. Máel Muire means ’servant of Mary’ in Old Irish. Clan Donnachaidh is descended from this Máel Muire through the Mórmáers of Atholl. Mórmáer, ‘great steward’, was the Scottish Gaelic equivalent of English ‘earl’. Wars of Scottish Independence The clan’s first recognized chief Dònnchadh Reamhar, “Stout Duncan”, (’Stout’, ie. ‘dependable, resolute’, not ‘fat’!) son of Andrew de Atholia, Latin ‘of Atholl‘, was a minor land-owner and leader of a kin-group in Highland Perthshire, and (it is said) an enthusiastic and faithful supporter of Robert I (1306-29) during the Wars of Scottish Independence. -

History of the Clan Mackenzie. With

National Library of Scotland *B00007817r Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/historyofclanmac1879mack HISTORY OF THE CLAN MACKENZIE; WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES. BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, Editor of the " Celtic Magazine" " The Prophecies of the Brahan Seer" "Historical Tales and Legends of tlie Highlands" &c, &c. LUCEO NON URO. (J INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCLXXIX. INVERNESS : rRINTED AT THE ADVERTISER OFFICE. ; To SIR KENNETH S. MACKENZIE OF GAIRLOCH, BARONET AS A SLIGHT BUT GENUINE ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF HIS EXCELLENT QUALITIES AS A REPRESENTATIVE HIGHLAND CHIEF, AND AS A GENEROUS AND BENEVOLENT LANDLORD, THIS HISTORY OF HIS CLAN IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. WHILE submitting to the Subscribers the HISTORY AND Genealogies of the Mackenzies, I feel fully alive to its literary demerits, but I am, at the same time, sensible of having done some little service to my Clan and to the Literature of the Highlands ; and it is no small pleasure to find that this has been already acknowledged in the most tangible and gratifying form—evidenced by the large and high-class List of Subscribers printed herewith. The amount of labour and research involved in the pro- duction of such a work is at once obvious. For generous and effectual aid to increase the number of my patrons, and for valuable genealogical notes, I am specially indebted to Major Thomas Mackenzie of the 78th Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs). For Mackenzie family MSS., and other valuable documents and information, I have to express my obligations to James F.