Sporting Multiculturalism: Toronto's Postwar European Immigrants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Newman, with Contributions by Graeme Burk and a Foreword by Ted Kotcheff

ECW PRESS Fall 2017 ecwpress.com 665 Gerrard Street East General enquiries: [email protected] Toronto, ON M4M 1Y2 Publicity: [email protected] T 416-694-3348 CANADA TABLE OF CONTENTS *HUHKPHU4HUKH.YV\W/LHK6ɉJL FANTASY 664 Annette Street, Toronto, ON M6S 2C8 MUSIC mandagroup.com 1 Bon: The Last Highway 14 Beforelife by Jesse Fink by Randal Graham National Accounts & Ontario Representatives: Joanne Adams, David Farag, TELEVISION YA FANTASY Tim Gain, Jessey Glibbery, Chris Hickey, Peter 2 Head of Drama 15 Scion of the Fox Hill-Field, Anthony Iantorno, Kristina Koski, by Sydney Newman by S.M. Beiko Carey Low, Ryan Muscat, Dave Nadalin, Emily Patry, Nikki Turner, Ellen Warwick 3 A Dream Given Form T 416-516-0911 I`,UZSL`-.\ќL`HUK FICTION [email protected] K. Dale Koontz 16 Malagash by Joey Comeau Quebec & Atlantic Provinces Representative: Jacques Filippi VIDEO GAMES 17 Rose & Poe T 855-626-3222 ext. 244 4 Ain’t No Place for a Hero by Jack Todd QÄSPWWP'THUKHNYV\WJVT by Kaitlin Tremblay 18 Pockets by Stuart Ross Alberta, Saskatchewan & Manitoba Representative: Jean Cichon HUMOUR 5 A Brief History of Oversharing T 403-202-0922 ext. 245 THRILLER by Shawn Hitchins [email protected] 19 The Appraisal by Anna Porter British Columbia NATURE Representatives: 6 The Rights of Nature MYSTERY Iolanda Millar | T 604-662-3511 ext. 246 by David R. Boyd [email protected] 20 Ragged Lake Tracey Bhangu | T 604-662-3511 ext. 247 by Ron Corbett [email protected] BUSINESS 7 Resilience CRIME FICTION Warehouse and Customer Service by Lisa Lisson Jaguar Book Group 21 Zero Avenue 8300 Lawson Road by Dietrich Kalteis SPORTS Milton, ON L9T 0A5 22 Whipped T 905-877-4411 8 Best Canadian by William Deverell Sports Writing Stacey May Fowles 23 April Fool UNITED STATES and Pasha Malla, eds. -

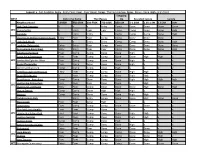

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Fixer Upper, Comp

Legend: x - Not Available, Entry - Entry Point, Fixer - Fixer Upper, Comp - The Compromise, Done - Done + Done, High - High Point Stepping WEST Get in the Game The Masses Up So-called Luxury Luxury Neighbourhood <$550K 550-650K 650-750K 750-850K 850-1M 1-1.25M 1.25-1.5M 1.5-2M 2M+ High Park-Swansea x x x Entry Comp Done Done Done Done W1 Roncesvalles x Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High Parkdale x Entry Entry x Comp Comp Comp Done High Dovercourt Wallace Junction South Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done x High Park North x x Entry Entry Comp Comp Done Done High W2 Lambton-Baby point Entry Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done Done Runnymede-Bloor West Entry Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Caledonia-Fairbank Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Corso Italia-Davenport Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High High x W3 Keelesdale-Eglinton West Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Rockcliffe-Smythe Fixer Comp Done Done Done High x x x Weston-Pellam Park Comp Comp Comp Done High x x x x Beechborough-Greenbrook Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x BriarHill-Belgravia x Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x Brookhaven--Amesbury Comp Comp Done Done Done High High High high Humberlea-Pelmo Park Fixer Fixer Fixer Done Done x High x x W4 Maple Leaf and Rustic Entry Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Done High Mount Dennis Comp Comp Done High High High x x x Weston Comp Comp Done Done Done High High x x Yorkdale-Glen Park x Entry Entry Comp Done Done High Done Done Black Creek Fixer Fixer Done High x x x x x Downsview Fixer Comp -

2014 Program

Kingston’s Readers and Writers Festival Program September 24–28, 2014 Holiday Inn Kingston Waterfront kingstonwritersfest.ca OUR MANDATE Kingston WritersFest, a charitable cultural organization, brings the best Welcome of contemporary writers to Kingston to interact with audiences and other artists for mutual inspiration, education, and the exchange of ideas that his has been an exciting year in the life of the Festival, as well literature provokes. Tas in the book world. Such a feast of great books and talented OUR MISSION Through readings, performance, onstage discussion, and master writers—programming the Festival has been a treat! Our mission is to promote classes, Kingston WritersFest fosters intellectual and emotional growth We continue many Festival traditions: we are thrilled to welcome awareness and appreciation of the on a personal and community level and raises the profile of reading and bestselling American author Wally Lamb to the International Marquee literary arts in all their forms and literary expression in our community. stage and Wayson Choy to deliver the second Robertson Davies lecture; to nurture literary expression. Ben McNally is back for the Book Lovers’ Lunch; and the Saturday Night BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2014 FESTIVAL COORDINators SpeakEasy continues, in the larger Bellevue Ballroom. Chair | Jan Walter Archivist | Aara Macauley We’ve added new events to whet your appetite: the Kingston Vice-Chairs | Michael Robinson, Authors@School, TeensWrite! | Dinner Club with a specially designed menu; a beer-sampling Jeanie Sawyer Ann-Maureen Owens event; and with kids events moved offsite, more events for adults on T Secretary Box Office Services T | Michèle Langlois | IO Sunday. -

Redress Movements in Canada

Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures -

Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective Bangarth, Stephanie D

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 19:58 International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective Bangarth, Stephanie D. Voices Raised in Protest: Defending Citizens of Japanese Ancestry in North America, 1942–49. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008 Caccia, Ivana. Managing the Canadian Mosaic in Wartime: Shaping Citizenship Policy, 1939–1945. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010 Champion, C.P. The Strange Demise of British Canada: The Liberals and Canadian Nationalism, 1964–68. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010 Iacovetta, Franca. Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006 Kaprielian-Churchill, Isabel. Like Our Mountains: A History of Armenians in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005 Lambertson, Ross. Repression and Resistance: Canadian Human Rights Activists, 1930–1960. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005 MacLennan, Christopher. Toward the Charter: Canadians and the Demand for a National Bill of Rights, 1929–1960. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004 Roy, Patricia E. The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941–67. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008 Christopher G. Anderson Miscellaneous: International Perspectives on Canada En vrac : perspectives internationales sur le Canada Numéro 43, 2011 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1009461ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1009461ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Conseil international d’études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (imprimé) 1923-5291 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Anderson, C. G. (2011). Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective / Bangarth, Stephanie D. -

African and Caribbean Philanthropy in Ontario

AT A GLANCE 1 000 000 000+Total population of Africa 40 000 000+Total population of the Caribbean 1 000 000+ Population of Canadians who identify as Black 85 Percentage of the Caribbean population who are Christian African 45 Percentage of Africans who identify as Muslim and Caribbean 40 Percentage of Africans who identify as Christian Philanthropy 85 Percentage of Jamaican-Canadians living in Ontario in Ontario In October 2013, the Association of Fundraising Professionals Foundation for Philanthropy – Canada hosted a conference that brought together charity leaders, donors and volunteers to explore TERMINOLOGY the philanthropy of the African and Caribbean CASE STUDY communities in Ontario. Here is a collection of Ubuntu: A pan-African philosophy or In 1982, the Black Business and insights from the conference and beyond. belief in a universal bond of sharing Professional Association (BBPA) wanted that connects all humans. to recognize the achievements of the six Black Canadian athletes who excelled at the Commonwealth Games that year. Organizers of the dinner invited Harry Jerome, Canada’s premiere track and field WISE WORDS athlete of the 1960s, to be the keynote “Ontario’s African and Caribbean communities are very distinct – both with respect to their speaker. Harry Jerome tragically died just histories and their relationship with Canada. The mistake the philanthropic sector could prior to the event and it was decided to turn the occasion into a tribute to him. The first easily make is treating these groups as a single, homogeneous community. What is most Harry Jerome Awards event took place on remarkable is the concept of ubuntu – or “human kindness” – and that faith in both of these March 5, 1983 and is now an annual national communities is very strong and discussed openly. -

Trailside Esterbrooke Kingslake Harringay

MILLIKEN COMMUNITY TRAIL CONTINUES TRAIL CONTINUES CENTRE INTO VAUGHAN INTO MARKHAM Roxanne Enchanted Hills Codlin Anthia Scoville P Codlin Minglehaze THACKERAY PARK Cabana English Song Meadoway Glencoyne Frank Rivers Captains Way Goldhawk Wilderness MILLIKEN PARK - CEDARBRAE Murray Ross Festival Tanjoe Ashcott Cascaden Cathy Jean Flax Gardenway Gossamer Grove Kelvin Covewood Flatwoods Holmbush Redlea Duxbury Nipigon Holmbush Provence Nipigon Forest New GOLF & COUNTRY Anthia Huntsmill New Forest Shockley Carnival Greenwin Village Ivyway Inniscross Raynes Enchanted Hills CONCESSION Goodmark Alabast Beulah Alness Inniscross Hullmar Townsend Goldenwood Saddletree Franca Rockland Janus Hollyberry Manilow Port Royal Green Bush Aspenwood Chapel Park Founders Magnetic Sandyhook Irondale Klondike Roxanne Harrington Edgar Woods Fisherville Abitibi Goldwood Mintwood Hollyberry Canongate CLUB Cabernet Turbine 400 Crispin MILLIKENMILLIKEN Breanna Eagleview Pennmarric BLACK CREEK Carpenter Grove River BLACK CREEK West North Albany Tarbert Select Lillian Signal Hill Hill Signal Highbridge Arran Markbrook Barmac Wheelwright Cherrystone Birchway Yellow Strawberry Hills Strawberry Select Steinway Rossdean Bestview Freshmeadow Belinda Eagledance BordeauxBrunello Primula Garyray G. ROSS Fontainbleau Cherrystone Ockwell Manor Chianti Cabernet Laureleaf Shenstone Torresdale Athabaska Limestone Regis Robinter Lambeth Wintermute WOODLANDS PIONEER Russfax Creekside Michigan . Husband EAST Reesor Plowshare Ian MacDonald Nevada Grenbeck ROWNTREE MILLS PARK Blacksmith -

10, 1969 32 PAGES 10T3NTS ^ [••••III1IMI1IIII1III W but Col

Ocean Oil Line Plan Alarms Howard SEE STORY Cloudy, Warm Clouding up this afternoon,- chance tf showers tonight. Red Bank, Freehold Sunny, hot tomorrow. Long Branch EDITION (Be* StUUi, Put 3); I Monmouth County*s Home Newspaper for 92 Years VOt, 93, NO. 9 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JULY 10, 1969 32 PAGES 10T3NTS ^ [••••III1IMI1IIII1III W But Col. Danowitz Would Rather Stay , Area Man's Unit Moving Out of Vietnam QUANG •fl'BI, Vietnam - His unit is being withdrawn March 8, 1965, at Da Nang. ath-'Marines leaving today S.C, who arrived in Vietnam . the 1st Battalion will leave.in "" cans, and from Jhe, weekly 'Col. Edward PrDanowitz of ' as part of the 25,00(Mnan- re- Their • withdrawal*- follows* consisted of Wcombat troops" three-months>agOv ^'r,m:4ust-->a-|ew~day«j<-spokesmen said,^•w-average»»-of—M3-^AmeriGan Red Bank,- N.J., commander duction in U.S: forces ordered by two days the departure and the rest communications, -„--,, «h.t «.,-,.,,k^j.. „,«>* K« u s headquarters, mean- dead in the first- 26 weeks of the»9th Marine Regiment, by President Nixon. of>the first elements of the administrative and other per- going." while, said 53 Americans this year. whose first units left Viet- The advance element of 120 U.S. Army's 9th Infantry Di- sonnel who will prepare the "I would just as soon stay," were^ killed Th action last Another 1,548 Americans nam today for Okinawa, was men, selected from all units vision from the Mekong Del- Okinawa base for the arrival said Maj. -

SFU Library Thesis Template

Linguistic variation and ethnicity in a super-diverse community: The case of Vancouver English by Irina Presnyakova M.A. (English), Marshall University, 2011 MA (Linguistics), Northern International University, 2004 BA (Education), Northern International University, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Irina Presnyakova 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Irina Presnyakova Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Thesis title: Linguistic variation and ethnicity in a super- diverse community: The case of Vancouver English Committee: Chair: Dean Mellow Associate Professor, Linguistics Panayiotis Pappas Supervisor Professor, Linguistics Murray Munro Committee Member Professor, Linguistics Cecile Vigouroux Examiner Associate Professor, French Alicia Wassink External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics University of Washington ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract Today, people with British/European heritage comprise about half (49.3%) of the total population of Metro Vancouver, while the other half is represented by visual minorities, with Chinese (20.6%) and South Asians (11.9%) being the largest ones (Statistics Canada 2017). However, non-White population are largely unrepresented in sociolinguistic research on the variety of English spoken locally. The objective of this study is to determine whether and to what extent young people with non-White ethnic backgrounds participate in some of the on-going sound changes in Vancouver English. Data from 45 participants with British/Mixed European, Chinese and South Asian heritage, native speakers of English, were analyzed instrumentally to get the formant measurements of the vowels of each speaker. -

CIC Diversity Colume 6:2 Spring 2008

VOLUME 6:2 SPRING 2008 Guest Editor The Experiences of Audrey Kobayashi, Second Generation Queen’s University Canadians Support was also provided by the Multiculturalism and Human Rights Program at Canadian Heritage. Spring / printemps 2008 Vol. 6, No. 2 3 INTRODUCTION 69 Perceived Discrimination by Children of A Research and Policy Agenda for Immigrant Parents: Responses and Resiliency Second Generation Canadians N. Arthur, A. Chaves, D. Este, J. Frideres and N. Hrycak Audrey Kobayashi 75 Imagining Canada, Negotiating Belonging: 7 Who Is the Second Generation? Understanding the Experiences of Racism of A Description of their Ethnic Origins Second Generation Canadians of Colour and Visible Minority Composition by Age Meghan Brooks Lorna Jantzen 79 Parents and Teens in Immigrant Families: 13 Divergent Pathways to Mobility and Assimilation Cultural Influences and Material Pressures in the New Second Generation Vappu Tyyskä Min Zhou and Jennifer Lee 84 Visualizing Canada, Identity and Belonging 17 The Second Generation in Europe among Second Generation Youth in Winnipeg Maurice Crul Lori Wilkinson 20 Variations in Socioeconomic Outcomes of Second Generation Young Adults 87 Second Generation Youth in Toronto Are Monica Boyd We All Multicultural? Mehrunnisa Ali 25 The Rise of the Unmeltable Canadians? Ethnic and National Belonging in Canada’s 90 On the Edges of the Mosaic Second Generation Michele Byers and Evangelia Tastsoglou Jack Jedwab 94 Friendship as Respect among Second 35 Bridging the Common Divide: The Importance Generation Youth of Both “Cohesion” and “Inclusion” Yvonne Hébert and Ernie Alama Mark McDonald and Carsten Quell 99 The Experience of the Second Generation of 39 Defining the “Best” Analytical Framework Haitian Origin in Quebec for Immigrant Families in Canada Maryse Potvin Anupriya Sethi 104 Creating a Genuine Islam: Second Generation 42 Who Lives at Home? Ethnic Variations among Muslims Growing Up in Canada Second Generation Young Adults Rubina Ramji Monica Boyd and Stella Y. -

HISTORICAL WALKING TOUR of Deer Park Joan C

HISTORICAL WALKING TOUR OF Deer Park Joan C. Kinsella Ye Merrie Circle, at Reservoir Park, c.1875 T~ Toronto Public Library Published with the assistance of Marathon Realty Company Limited, Building Group. ~THON --- © Copyright 1996 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Toronto Public Library Board Kinsella. Joan c. (Joan Claire) 281 Front Street East, Historical walking tour of Deer Park Toronto, Ontario Includes bibliographical references. M5A412 ISBN 0-920601-26-X Designed by: Derek Chung Tiam Fook 1. Deer Park (Toronto, OnL) - Guidebooks. 2. Walking - Ontario - Toronto - Guidebooks Printed and bound in Canada by: 3. Historic Buildings - Ontario - Toronto - Guidebooks Hignell Printing Limited, Winnipeg, Manitoba 4. Toronto (Ont.) - Buildings, structures, etc - Guidebooks. 5. Toronto (OnL) - Guidebooks. Cover Illustrations I. Toronto Public Ubrary Board. II. TItle. Rosehill Reservoir Park, 189-? FC3097.52.K56 1996 917.13'541 C96-9317476 Stereo by Underwood & Underwood, FI059.5.T68D45 1996 Published by Strohmeyer & Wyman MTL Tll753 St.Clair Avenue, looking east to Inglewood Drive, showing the new bridge under construction and the 1890 iron bridge, November 3, 1924 CTA Salmon 1924 Pictures - Codes AGO Art Gallery of Ontario AO Archives of Ontario CTA City of Toronto Archives DPSA Deer Park School Archives JCK Joan C. Kinsella MTL Metropolitan Toronto Library NAC National Archives of Canada TPLA Toronto Public Library Archives TTCA Toronto Transit Commission Archives ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Woodlawn. Brother Michael O'Reilly, ES.C. and Brother Donald Morgan ES.C. of De La This is the fifth booklet in the Toronto Public Salle College "Oaklands" were most helpful library Board's series of historical walking in providing information.