Chenjerai-Kumanyika-Review.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

Spellberg, Denise CV

DENISE A. SPELLBERG CURRICULUM VITAE 128 Inner Campus Drive, B7000 [email protected] Department of History, University of Texas office: GAR 3.208 Austin, Texas EDUCATION • Columbia University, Ph.D. in History, May 1989 • Columbia University, M. Phil in History, October 1984 • Columbia University, M.A. in History, May 1983 • Smith College, B.A. in History, May 1980, Phi Beta Kappa ACADEMIC POSITIONS •Professor, Department of History and Middle Eastern Studies, September 2014-present Fellow of John E. Green Regents Professorship in History, 2015-2016 •Associate Professor, Department of History and Middle Eastern Studies, 1996-2014 • Assistant Professor, Department of History and Middle Eastern Studies, 1990-1995 • Faculty Affiliate, Department and Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Islamic Studies, American Studies, Religious Studies, Medieval Studies, the Center for Gender and Women’s Studies, and the Center for European Studies, 1990- present •Research Associate and Visiting Lecturer in the Women’s Studies and World Religions Program, Harvard Divinity School, Harvard University, 1989-90 •Lecturer in European History, Department of History, University of Massachusetts, Lowell, 1988-89 ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS • Director, History Department Honors Program, 2014-2021 • Associate Director, Medieval Studies Program, 2007-2008 • Director, Religious Studies Program, 1995-1996 • Designer and core faculty for Tracking Cultures, an intensive undergraduate study abroad program, dedicated to the analysis of Islamic and Spanish cultural precedents surviving in Mexico, Texas, and the American Southwest, 1995-2003 1 PUBLICATIONS Authored Books Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders. Alfred A. Knopf, October, 2013. 392 pages. Paperback, Vintage Press, July 2014. Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past: The Legacy of ‘A’isha bint Abi Bakr, Columbia University Press, 1994. -

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg Shiny little platters. Not even five inches across. How could they possibly contain the soundtrack of four decades? How could the phone calls, the encounters, the danger, the desperation, the exhilaration and big, big laughs from two score years be compressed onto a handful of CDs? If you’ve lived with NPR, as so many of us have for so many years, you’ll be astonished at how many of these reports and conversations and reveries you remember—or how many come back to you (like familiar songs) after hearing just a few seconds of sound. And you’ll be amazed by how much you’ve missed—loyal as you are, you were too busy that day, or too distracted, or out of town, or giving birth (guess that falls under the “too distracted” category). Many of you have integrated NPR into your daily lives; you feel personally connected with it. NPR has gotten you through some fairly dramatic moments. Not just important historical events, but personal moments as well. I’ve been told that a woman’s terror during a CAT scan was tamed by the voice of Ira Flatow on Science Friday being piped into the dreaded scanner tube. So much of life is here. War, from the horrors of Vietnam to the brutalities that evanescent medium—they came to life, then disappeared. Now, of Iraq. Politics, from the intrigue of Watergate to the drama of the Anita on these CDs, all the extraordinary people and places and sounds Hill-Clarence Thomas controversy. -

PBS Newshour Coverage Of

Prehistoric Road Trip | 13 American Masters/Terrence McNally | 18 WCRB’s Updated Mobile App | 27 wgbh.org ON AIR, ONLINE, ON THE GO MEMBER GUIDE | JUNE 2020 Summer is a critical time to keep kids engaged in learning, and we’re here to help. This past spring, students everywhere used our distance learning tools to keep growing and exploring the world around them. In partnership with PBS, our special blocks of commercial-free public media programs provided critical at-home learning for 6th through 12th graders across the country. As always, PBS LearningMedia gave teachers and students alike access to thousands of free, standards-based lesson plans and activities so they didn’t have to skip a beat. Your support made this momentum possible, and we won’t stop here. Our efforts will continue through the summer, giving kids the resources they need to keep moving forward. Whether it’s learning about the summer solstice or Freedom Summer, we’re here for kids and it’s all because of you. wgbh.org/distancelearning PBSLearningMedia.org Where to Tune in From the President TV Voices of Diversity f we’ve learned anything over the past few months, I it’s how our own worlds can be compressed into a Digital broadcast FiOS RCN Cox Charter TV YouTube Comcast few small rooms. Public media programs have always brought the world to WGBH 2 2.3 2 2 2 2 2 * us, and this month we’re pleased to continue that mission, sharing cultures WGBH 2 HD 2.1 802 502 602 1002 782 n/a from across the globe and close to home. -

WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2009

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData WGLT Program Guides Arts and Sciences Fall 9-1-2009 WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2009 Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg Recommended Citation Illinois State University, "WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2009" (2009). WGLT Program Guides. 226. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg/226 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in WGLT Program Guides by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLT Radio Faces 2009 GLT presents An evening with NPR's All Things Considered® This year's GLT Radio Faces guest is reporter and All Things Considered®co-host Melissa Block. She is part of the NPR team that won both George Foster RADIO Peabody and Edward R. Murrow Awards for the with sr.2ecial quest Brendan Banaszak coverage of the earthquake in China last year. GLT I FACES Assistant News Director Charlie Schlenker talked with Melissa about part of that experience. Friday, November 6, 2009 Charlie Schlenker: During one story in Chengdu you followed a family through 5:00 - 6:30 pm - Cocktail hour ($100 level only) a long, heart-wrenching day as they searched for relatives. In part of that coverage 6:45 - 9:30 pm - Dinner and presentation your voice carried emotion and distress. C learly, you had the necessary detachment (both ticket levels) to report the story and to find the absolute best way to tell it, but you were recogniz ing and acknowledging the human qualities of what was going on. -

Commencement

ONE HUNDRED AND THIRD COMMENCEMENT MONDAY, MAY 15, 2017 The Program PROCESSIONAL* INTRODUCTORY REMARKS John R. Kroger, President WELCOME Roger M. Perlmutter ’73, Chairman, Board of Trustees ALUMNI WELCOME Richard Roher ’79 REED COLLEGIUM MUSICUM “As Torrents in Summer” from Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf, Op. 30 Music by Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Text by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882) “You are the New Day” Music and text by John David (b. 1946), arr. Bob Chilcott COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS INTRODUCTION John R. Kroger, President ADDRESS Arun Rath ’92 CONFERRING OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS John R. Kroger, President CONFERRING OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES John R. Kroger, President RECESSIONAL* MARSHALS Commencement Marshal Jeffrey Parker, George Hay Professor of Economics Student Marshals Arthur Glasfeld, Amgen-Perlmutter Professor of Chemistry Virginia Hancock ’62, Professor of Music, Emerita Faculty Marshals Margot Minardi, Associate Professor of History & Humanities Sonia Sabnis, Associate Professor of Classics and Humanities * The audience is requested to rise for the processional and recessional. Please remain in place during the recessional until the faculty and class of 2017 have left the tent. Sign language interpretation is provided by Access Services Northwest. Our bagpiper is Ogden Kimberly. Graduates and guests are invited to a reception after the ceremony in the Gray Campus Center Quad. Arun Rath ’92 Arun Rath has distinguished himself in public media as a reporter, producer, and editor. In his current role as a shared correspondent for NPR and Boston-based public station WGBH, he covers a variety of beats, from neuroscience and the arts to the war court in Guantanamo Bay. -

NPR Ends Production of Tell Me More

NPR Ends Production of Tell Me More We are sad to announce that Tell Me They have eliminated 28 positions but More, the NPR news-talk program are keeping Martin on staff to continue currently heard at 10:00 weekday producing coverage of these subjects mornings on KIOS, will end which will be aired on NPR’s other production in August. Since 2007, the newsmagazines like Morning Edition show has become a well-loved part of and All Things Considered. The show’s midday programming for many KIOS executive producer, Carline Watson, listeners. Hosted by award-winning will also remain on staff. In discussing journalist Michel Martin, the show the cancelation of the show, Watson covers a broad range of issues, using an has said that NPR continues to be interview-style format to feature diverse strongly committed to serving diverse M2007 NPR By Stephen Voss voices. Martin is not afraid to ask audiences and feels optimistic about its celebration of National Poetry Month important questions even if it means ability to do so going forward. “We’re which invites listeners to share their engaging in difficult conversations. in a different era than we were, even short poems on Twitter, some of which Tell Me More has been commended for five or six years ago,” she says. “There are selected and read on air. Also sure covering issues which are otherwise is in fact an opportunity to reach a to be remembered fondly are Barber underrepresented in news including larger audience across platforms ... not Shop and Beauty Shop: candid weekly race, gender, family and faith. -

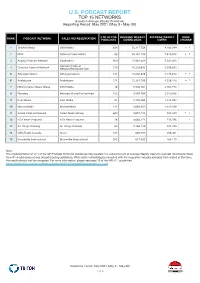

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30)

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30) # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 Stitcher Media SXM Media 459 35,317,758 9,163,399 1 2 NPR National Public Media 55 35,162,199 7,425,526 1 3 Audacy Podcast Network Cadence13 500 17,982,442 5,542,005 Cumulus Podcast 4 Cumulus Podcast Network Network/Westwood One 270 15,225,592 3,556,832 5 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 134 13,050,876 4,173,613 1 6 Audioboom Audioboom 274 12,281,759 4,326,418 1 7 NBCUniversal News Group SXM Media 46 9,926,761 2,764,770 8 Wondery Wondery Brand Partnerships 102 9,589,764 2,910,636 9 Kast Media Kast Media 93 3,795,469 1,514,087 10 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 114 3,698,251 1,437,168 11 Salem Podcast Network Salem Media Group 662 2,691,743 534,539 1 12 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 48 2,665,171 735,796 1 13 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 52 2,166,142 944,325 14 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 333 685,707 236,461 15 Bonneville International Bonneville International 252 647,352 184,170 Note: The implementation of v2.1 of the IAB Podcast Technical Guidelines has resulted in a reduced count of Average Weekly Users for podcast downloads made from IP v6 addresses across all participating publishers. While both methodologies complied with the respective industry standard that existed at that time, the results should not be compared. -

Firstchoice Wusf

firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • maY 2010 A Place in the Sun St. Petersburg: New Place in the Sun celebrates downtown St. Petersburg’s renaissance. This 30-minute documentary, produced by WUSF, was written, directed and narrated by Tampa filmmaker Larry Elliston and underwritten by the Florida Humanities Council. Why St. Petersburg? “It’s a perfect example of the new urbanism that’s blossoming around the country,” says Elliston. “As baby boomers and younger people turn to urban living, St. Petersburg, with its waterfront and historic charm, walkability, and vibrant arts and performance scene, is an ideal destination.” Elliston’s ode to St. Pete “covers a lot of ground,” including a look back at its history, and interviews with the city’s movers and shakers. Airs on WUSF TV, Saturday, May 15, at 8 p.m., and repeats Sunday, May 16, at 9 p.m. from the wusf gm Buy Online and May Support WUSF Greetings! Did you know that every time you buy something s we look forward to the summer online at season, it’s the perfect time to look back Amazon.com, at the busy months behind us. We have A you have the so much good news to share. opportunity to First, we thank you, our dedicated members, help WUSF Public who showed your support during our March radio Broadcasting? and TV membership campaigns. Thanks to you, we If you click the link greeted nearly 1,600 new members and received to Amazon.com pledges of support totaling $550,000. The tough on our website, economic times are starting to take their toll at WUSF Public Broadcasting, and we saw evidence wusf.org, of that during our membership campaigns. -

2020 CPB Report

Local Content and Service 2020 GBH exists to engage, illuminate and inspire. Our vision is to be a pioneering leader in media that strengthens, includes and serves our diverse community, fostering growth and empowering individuals. INTRODUCTION 2020 In Service to the Community in a Year Like No Other 2020 was a year unlike any other, requiring all of us to recalibrate. The COVID-19 lockdown prompted a rapid pivot across all of GBH’s programs, events and services in order to continue to provide engaging and inspiring resources for our community. GBH worked to engage in new ways during this challenging time by: • Creating a new daily call-in radio program that focused on the impact of COVID-19 in our neighborhoods and fielded questions from listeners across the state • Airing and streaming musical performances when concert halls were closed • Providing broadcast and online resources for remote learning across the Commonwealth • Producing a virtual graduation ceremony for our high school seniors • Partnering with local community organizations and institutions to create dozens of new virtual events and forums including our first community book club and our monthly multiplatform community dialogue on The State of Race The State of Race panel © GBH Throughout the year we partnered with local organizations and community groups including the NAACP, Handel and Haydn Society, Boston Public Library, the Museum of Fine Arts, the cross-cultural professional organization Get Konnected, the Martin Luther King, Jr., legacy nonprofit King Boston, the Huntington Theatre Company and more to help amplify and support their efforts. Our nation’s reckoning with racism prompted us to deeply reflect and commit to making meaningful changes in how we operate and to offer new programming. -

FY2013 Annual Report Mission Arizona Public Media Informs, Inspires, and Connects Our Community by Bringing People and Ideas Together

FY2013 annual report Mission Arizona Public Media informs, inspires, and connects our community by bringing people and ideas together. Vision We connect you to the community and the world through the intellectual and creative resources of the University of Arizona. We are leaders within the community and industry, embracing new technologies, ideas, and partnerships. Our efforts in service to the community are sustained by the investment of individual supporters in partnership with the University of Arizona, the business community, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Values Accountability. AZPM staff, volunteers, and students are committed to meeting the needs and exceeding the expectations of our audiences and colleagues with honesty and integrity. We are dedicated to uncompromising journalistic values, high-quality production, and the best use of technology. Growth. We believe that meaningful long-term impact comes through innovation and through mutually beneficial relationships with production partners. We accept reasonable risk in our strategic investments and reward performance, in order to foster sustained growth. Ideas. Through our work we promote an open exchange of knowledge, ideas, and experiences. We value individual contributions and respect the differences of our staff and partners. Diversity of opinion and constructive, open debate are encouraged and appreciated. As we are an operating unit of the University of Arizona, continual learning and education are at the core of our culture. Results. We set challenging goals and achieve measurable results working together as members of a unified team striving daily to improve performance in service to our community. Our decisions will be guided by what best serves audiences.