Use of Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Swedenborgian Church

2017 Journal of the Swedenborgian Church No. 195 THE SWEDENBORGIAN CHURCH UNITED STATES AND CANADA INCORPORATED 1861 THE GENERAL CONVENTION OF THE NEW JERUSALEM IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ANNUAL SESSION “ROOTED IN OUR HISTORY, GROWING IN THE WORD” JULY 8 - JULY 12, 2017 WEST CHESTER UNIVERSITY, WEST CHESTER, PA ANNUAL THEME THE YEAR OF THE NEW JERUSALEM JULY 1, 2017-JUNE 30, 2018 RECORDING SECRETARY KAREN CONGER 314 APOLLO CIRCLE BISHOP, CA 93514-7051 P: (760) 872-3392 E: [email protected] CENTRAL OFFICE SAMANTHA JOHANSON, OPERATIONS MANAGER 50 QUINCY STREET CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138-3013 P/F: (617) 969-4240 E: [email protected] W: www.swedenborg.org C The Faith and Aims of Our Church .......................................... 1 The Offi cers of The Swedenborgian Church............................ 3 General Council ....................................................................... 3 Council of Ministers .............................................................. 13 Roll of Ministers .................................................................... 16 Auxiliary and Associated Bodies ........................................... 28 Minutes From the One Hundred Ninety-Third Session .........30 Convention Preachers Since 1959 ......................................... 42 Memorial ................................................................................ 44 Reports of Offi cers, Boards, Committees, Support Units and Associated Bodies .......................................................... 48 Church Statistics ................................................................... -

The New Buddhism: the Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition

The New Buddhism: The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS the new buddhism This page intentionally left blank the new buddhism The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman 1 1 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and an associated company in Berlin Copyright © 2001 by James William Coleman First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, 10016 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2002 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coleman, James William 1947– The new Buddhism : the western transformation of an ancient tradition / James William Coleman. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-19-513162-2 (Cloth) ISBN 0-19-515241-7 (Pbk.) 1. Buddhism—United States—History—20th century. 2. Religious life—Buddhism. 3. Monastic and religious life (Buddhism)—United States. I.Title. BQ734.C65 2000 294.3'0973—dc21 00-024981 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America Contents one What -

12Pm Dharma Bum Temple 541 2Nd Ave, San Diego, 92101 Limited to 12 People – Sign up at DBT

A Request for Financial Support As presented in the following report, The Dharma Bum Temple has been serving our local community by offering free meditation, homeless outreach, prison outreach, animal outreach, recovery programs, meditation for kids, college programs and more since 2006. We have been operating for ten years in a small loft and now have an opportunity to strengthen our community by acquiring a new property. This new facility will allow us to expand our current operations and develop additional programs while providing a comfortable location to gather. Our intention is to foster an accepting and safe space where people from all races, genders, sexual orientations, religions and abilities come together to build community. To share the daily practice of loving-kindness, compassion, joy and equanimity while helping people live a gentle life. We are requesting financial support for our capital campaign, which will allow us to purchase the 6,300 square foot Swedenborgian Church in the University Heights neighborhood of San Diego. The building was built in 1927 and designed by renowned California architect Louis J. Gill. This is an opportunity not only to grow our community, but also to retain the beauty and care of this historical building and ensure it is not torn down. In just 71 days from October 29th to January 8th, the community believed in this endeavor enough to raise a total of $326,154 from 924 donors. We are in escrow yet we still need to raise $163,846 by February 14, 2017 for the remainder of the down payment. Auspiciously enough, our fundraising time turns out to be 108 days. -

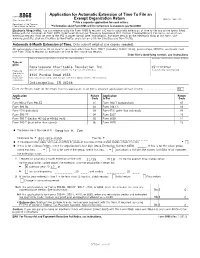

RCF-990-2017.Pdf

Application for Automatic Extension of Time To File an Form 8868 Exempt Organization Return OMB No. 1545-1709 (Rev. January 2017) GFile a separate application for each return. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service GInformation about Form 8868 and its instructions is at www.irs.gov/form8868. Electronic filing (e-file). You can electronically file Form 8868 to request a 6-month automatic extension of time to file any of the forms listed below with the exception of Form 8870, Information Return for Transfers Associated With Certain Personal Benefit Contracts, for which an extension request must be sent to the IRS in paper format (see instructions). For more details on the electronic filing of this form, visit www.irs.gov/efile, click on Charities & Non-Profits, and click on e-file for Charities and Non-Profits. Automatic 6-Month Extension of Time. Only submit original (no copies needed). All corporations required to file an income tax return other than Form 990-T (including 1120-C filers), partnerships, REMICs, and trusts must use Form 7004 to request an extension of time to file income tax returns. Enter filer's identifying number, see instructions Name of exempt organization or other filer, see instructions. Employer identification number (EIN) or Type or print Renaissance Charitable Foundation Inc. 35-2129262 Number, street, and room or suite number. If a P.O. box, see instructions. Social security number (SSN) File by the due date for filing your 8910 Purdue Road #555 return. See City, town or post office, state, and ZIP code. For a foreign address, see instructions. -

Thiền Tập Trong Đời Thường

THIỀN TẬP TRONG ĐỜI THƯỜNG NGUYÊN GIÁC Nhà xuất bản Ananda Viet Foundation Copyright © 2017 Nguyên Giác All rights reserved. ISBN-10: 1546358137 ISBN-13: 978-1546358138 LỜI THƯA Thiền Tập Trong Đời Thường là một tuyển tập gồm nhiều bài viết, hy vọng giúp độc giả nhìn thấy từng khoảnh khắc hiện tiền với cảm thọ hạnh phúc hơn, yêu thương hơn, và tự chữa trị nhiều bệnh về thân- tâm. Tuyển tập cũng ghi lại một số cuộc nghiên cứu thực dụng về các Thiền pháp chữa trị bệnh tự kỷ và bệnh chậm trí, giữ gìn làn da đẹp cho nhan sắc, tăng trí tuệ nhạy bén, ngăn ngừa trầm cảm… Và, cũng có một số bài với chủ đề khác. Hiển lộ chung quanh chúng ta đều là các hiện tướng không khác, như thành quách phố thị, như những gì được thấy nghe hay biết… nhưng có người hạnh phúc được bất kể mọi gian nan gặp phải, và có người đi khắp cùng trời cuối đất cũng không thấy được chút nào bình an. Tuyển tập này là một mời gọi tỉnh thức nhìn về các khoảnh khắc trong đời, để chúng ta sống an vui, hiểu nhau hơn, thương nhau hơn để kiến lập một xã hội xa lìa bạo động. Nguyên Giác, 2017 . MỤC LỤC LỜI THƯA i LỜI GIỚI THIỆU CỦA CƯ SĨ TÂM DIỆU 1 THIỀN TẬP VÀ NHAN SẮC 1 2 THIỀN TẬP CHO CẢNH SÁT 9 3 THIỀN TẬP CHỮA BỆNH CHẬM TRÍ 17 4 THIỀN NHƯ PHÁP GIẢM ĐAU 25 5 CÀ PHÊ VÀ THIỀN 35 6 ĂN CHAY ĐỂ CỨU ĐỊA CẦU 43 7 ĐÁ BANH VÌ QUÊ NHÀ 50 8 HỘI SINH VIÊN PHẬT TỬ DELTA BETA TAU 56 9 THIỀN TÔNG TẠI CUBA 63 10 MỘT GÓC VẮNG LẶNG 70 11 TẬP THIỀN CHẠY BỘ 76 12 THIỀN TÔNG VÀ THI CA 83 13 NÓI GÌ VỚI GIỚI TRẺ VỀ PHẬT GIÁO? 106 NGUYÊN GIÁC 14 THIỀN TẬP VÀ BẠO LỰC 124 15 THẾ VẬN và THIỀN TẬP 132 16 -

The Generation Dharma Teachers

THE GENERATION X 2019 DHARMA TEACHERS CONFERENCE June 12-16, 2019 Great Vow Zen Monastery TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Message from the Planning Committee 2 GenX 2019 Schedule 3 Conference Schedule Day-by-Day 4 Program Details: The Ethical Transformation, Panel on Integrity 7 and Enlightenment About Great Vow Zen Monastery 8 Great Vow Zen Monastery Map 9 Participants List 10 Notes 13 Thank You 17 1 GENX2019 WELCOME Welcome to the 5th Gen X Teachers gathering. What an amazing achievement. We have been meeting as an inter-lineage community, convening different teachers from all different forms of Buddhism, every 2 years since 2011. This community is unique in that it changes every time we meet, it’s never the exact group of teachers coming together. Every one of you helps to create a space for practice on and off the cushions, reflection, dialogue, and networking at these gatherings. It’s an opportunity to drop our teacher roles and relate to each other as peers, friends and fellow dharma practitioners. We encourage people to intentionally reach out and connect with people from different lineages and take the opportunity to sit down for lunch or go for a walk with someone you don’t know. This is your gathering, if you just need time to be in the beautiful landscape that Great Vow is situated in, then please take that time. We hope that the gathering will nourish and inspire you. Thank you all for taking the time out of your busy lives to join us. Blessings from the 2019 Planning committee. -

Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism

Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism Volume I Literature and Languages Preview Editor-in-Chief: Jonathan A. Silk Consulting Editors: Oskar von Hinüber Vincent Eltschinger preview_BEB_v3.indd 1 31-07-14 10:57 Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism (6 vols.) Editor-in-Chief: Jonathan A. Silk, Leiden University Consulting Editors: Oskar von Hinüber, Albert-Ludwigs University of Freiburg, and Vincent Eltschinger, Austrian Academy of Sciences Set (6 vols.) • brill.com/enbu • ISBN 978 90 04 28469 2 • Hardback (6 vols. of approx. 750 pp. each) • List price EUR 1245.- / US$ 1944.- • Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 2 South Asia, 29/1-6 Volume 1: Buddhist Literatures • brill.com/ho2-ho2-29 • Forthcoming 2015 • ISBN 978 90 04 28343 5 • Hardback (approx. 750 pp.) • List price EUR 249.- / US$ 346.- • Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 2 South Asia, 29/1 It has been evident for many years that no authoritative, reliable, and up-to-date reference work on Buddhism yet exists in any language. Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism aims to fill that gap with a comprehensive work, presented in two phases: a series of six thematic volumes including an index volume, addressing issues of global and regional importance, to be followed by an ever-expanding online resource providing access both to synthetic and comprehensive treatments and to more individuated details on persons, places, texts, doctrinal matters, and so on. Illustrated with maps and photographs, and supplemented with extensive online resources, the print version of the thematic encyclopedia will present the latest research on the main aspects of the Buddhist traditions in original essays written by the world’s foremost scholars. -

Vol.102 #01 Jan 03 1986.Pdf

•• •• aCl lC Cl lZCll National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens league Newsstand: 25¢ (60e Postpaid) ISSN: 003)-8579/Whole No. 2,371 I Vol. 102 No.1 941 E. 3rd St. #200, Los Angeles, CA 90013 (213) 626-6936 Friday, January 3-1 0, 1986 Nikkei senators, reps to be honorees at LEG dinner LOS ANGELES-Pacific South they will attend, according to din Tickets are $100 per person or west DistrictJACL will hold ''Re ner chair Toy Kanegai $1,<XX> per table. Cocktail hour dress-An American Promise," a Mistress of ceremonies will be begins at 6 p.m, followed by din national kick-off dinner to raise KCBS-TV news anchor Tritia ner at 7. A special silent auction funds for JACL Legislative Edu Toyota. will be held during the program. cation Committee (LEC) Jan. 17 Proceeds from the dinner will JACL chapters are encouraged at the Bonaventure Hotel. be used by LEC to finance and to support the event as table Sens. Daniel Inouye and Spark cany out the lobbying needed to sponsors. Matsunaga (both D-Hawaii) and secure passage of legislation, For reservations OJ: infonna Reps. Nonnan Mineta and Rob now pending in both houses of tion, contact Toy Kanegai at (213) ert Matsui (both D-Calif) will be Congress, which would provide 820-5250 or Leslie Furukawa at honored for their leadership in monetary compensation for J a (213) fJ2':l-71Zl. Special room rates and contributions to the redress panese Americans interned dur are available for attendees from effort. All four have confirmed ingWW2. -

Parergonality in Zen Buddhism and Non-Idiomatic Improvisation

DHARMA NOISE: PARERGONALITY IN ZEN BUDDHISM AND NON-IDIOMATIC IMPROVISATION DANIEL PAUL SCHNEE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MARCH2013 © Daniel Paul Schnee, 2013 ABSTRACT 11 The objective of this dissertation is to explore philosophical and practical approaches to the study of improvisation in relation to Japanese Zen Buddhist doctrine and aesthetics. It specifically asks whether free form (non-idiomatic) improvisation can be practiced, and Zen Buddhism's efficacy in establishing a structured regimen for technical study on a musical instrument. In order to complete this research objective, the historical development of Zen Buddhist doctrine and aesthetics is investigated and shown to be a non-unified rubric. Using the concept of the parergon, it is then demonstrated that practicing is an appropriate activity for improvisation when supplemented by the kata forms of Zen-influenced Japanese arts. The result of such supplementation in .this case takes the form of a series of original chromatic exercises developed as a paradigm that itself acts as a supplement to improvisation. The establishment of such a regimen also suggests further research into the topic of pedagogy and Shintoism as an aesthetic or theological supplement, as well as gender issues in creative perfonnance. 11l TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 11 Table of Contents 111 1. Chapter One: Introduction Dharma Noise 1 Statement of the Central Problem 3 Literature Review 5 A Brief Introduction to Buddhism and Zen 18 2. Chapter Two: Improvisation 30 Introduction 30 Defining Improvisation 30 Improvisation in Western Musical Culture 31 Free Jazz 37 Free Improvisation 41 Non-Idiomatic Improvisation 45 Improvisation in Traditional Music of the Far East 50 Noh Theater Music and Improvisation 53 The Hana Concept 63 I-guse as Stillness/Silence 66 Conclusion 68 3. -

Buddhists Bring Meditation to the Streets and Subways of NYC

Get the latest in Buddhism, delivered to your inbox × Enter your email address here... SIGN UP Buddhism Life & Culture How to Meditate Teachers News Our Magazines About Us Store Subscribe Buddhists bring meditation to the streets and subways of NYC BY SAM LITTLEFAIR| NOVEMBER 16, 2016 More A new organization called Buddhist Insights is helping New Yorkers meditate in all manner of surprising places — and to make friends with their surroundings. And they’re garnering attention, too. Meditating in a New York subway station. Photos courtesy of Buddhist Insights. New Yorkers may not think of the city’s gritty streets as a place to find inner peace, but a new group called Buddhist Insights is aiming to change that. “There’s this idea that you have to escape New York to find peace and quiet,” explains Buddhist Insights co-founder Giovanna Maselli. To challenge that idea, she and her co- founder, Buddhist monk Bhante Suddhaso, hold meditation classes in unconventional locations around the city. They call them “street retreats.” “The street retreats started as a fun thing to do,” explains Maselli. “But they got a lot of positive feedback. People realized that they could meditate anywhere.” A Buddhist Insights class in a building lobby. Buddhist Insight’s mission is to connect New Yorkers to Buddhist monastics. Maselli explains that when she was trying to find a monastic teacher in 2015, she came up empty. So she collaborated with Suddhaso, a monk in the Thai Forest Tradition of Theravada Buddhism, to start the organization. He and Maselli, who has a background in creative consulting, almost accidentally invented their concept of hosting meditation classes in the street. -

Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism: Myōshinji, a Living Religion

Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd i 12/20/2007 6:19:39 PM Numen Book Series Studies in the History of Religions Series Editors Steven Engler (Mount Royal College, Canada) Richard King (Vanderbilt University, U.S.A.) Kocku von Stuckrad (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Gerard Wiegers (Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands) VOLUME 119 BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd ii 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism Myōshinji, a living religion By Jørn Borup LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd iii 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM On the cover: Myōshinji honzan in Kyoto. Photograph by Jørn Borup. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISSN 0169-8834 ISBN 978 90 04 16557 1 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd iv 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM For Marianne, Mads, and Sara BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd v 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd vi 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................... -

A Shin Buddhist-Catholic Dialogue! by Kenneth Paul Kramer, San Jose State University, San Jose

Through Each Other's Eyes: A Shin Buddhist-Catholic Dialogue! by Kenneth Paul Kramer, San Jose State University, San Jose Since we have been a dialogue And can hear each olber. (H<llderiin) f I could introduce you to a practice that Jodo ToldwlI About tha~ also, I am very vague. I I Shin Priest SMjun Bando calls "etemally respond to your questions with the name Tokiwa enlightening:~ and Catholic Professor of Japanese That is my responsibility in this world. Religions (at Sophia University) Ernest Piryns calls "the way to greater salvation,'" would you be BEING A DIALOGUE at all interested? This presentation will address what I take 10 be the future presence of the Shin I began the series of dialogues with two Buddhist-Catholic dialogue by focusing on a spe assumptions, the fIrSt of which needed immediate cific method to facilitate tbat encounter, the inter correction, namely that Buddhists are not as inter view-dialogue, and then by reporting instances of ested in the dialogue as Christians are. Michio such exchanges which occurred during a recent Shinozaki (Dean of the RissbO KOsei-Kai Semi trip to Japan (1991). My purpose in the conducted nary in Tokyo) lold me in an interview that when dialogues was to travel beyond the usual discus he was senllo America by President Niwano, he sion of epistemological, leleological and meta was told first to see Christiartity from the point of physical categories of comparison (not thaI these view of The Lotus Sutni, and then 10 see The Lotus are unimportant), in order to inquire inlO a more Sutra from the point of view of Christianity.