Just When You Thought It Was Safe to Go Back Into the Bluebook: Notes on the Fifteenth Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lovend Over Vaardigheden, Kritisch Op De Roosters

Lieve Ingrid Prof. Heeren Hero Less workload Psychische6 problemen? Psycholoog “Het8-9 is de hoogste tijd voor een bèta- Jenny4 Slatman about Franҫoise Fasos:5 Reduce work pressure, imple- geeft antwoord in nieuwe serie faculteit in Maastricht” Dastur’s beautiful voice ment repair plans and a healthy budget 5 www.observantonline.nl Onafhankelijk weekblad van de Universiteit Maastricht | Redactieadres: Postbus 616 6200 MD Maastricht | Jaargang 35 | 25 september 2014 Genootschap Phylla van studentenvereniging Koko hoopt dit jaar nog een officieel dispuut te worden. Zie pagina 7 Foto: Joey Roberts Free Dutch courses very popular Keuzegids-presentatie over de Maastrichtse studentenoordelen In the past year, 93 per cent of all foreign first- was 18.5 per cent. year bachelors – 1,200 were expected – partici- First-year foreign bachelors again have the oppor- pated in one of the two free Basic Dutch courses. tunity to take one or two free Basic Dutch courses Lovend over vaardigheden, Two thirds of them passed the exam. this year. What is new this year, is the fact that the courses are now also available for master’s kritisch op de roosters It was the first time that Maastricht University had students. The cost for the master’s students will De faculteiten rechten en Humanities & Sciences kleine dingen”, zegt Steenkamp. “Studenten zijn granted the long-desired wish of various student be paid from the UM Innovation Fund for 2014- hebben een bewonderenswaardige inhaalslag nauwelijks in staat om de inhoud en vorm van groups: free Dutch courses for foreign students. 2016. gemaakt, terwijl Health, Medicine and Life een toets tegen het licht te houden. -

Kate Bush the Whole Story Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kate Bush The Whole Story mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: The Whole Story Country: France Released: 1986 Style: Art Rock, Downtempo, Synth-pop, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1822 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1324 mb WMA version RAR size: 1584 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 737 Other Formats: MP4 WMA MP3 TTA VQF AA ADX Tracklist Hide Credits Wuthering Heights (New Vocal) A1 4:57 Producer [Originally] – Andrew Powell Cloudbusting A2 5:09 Producer – Kate Bush The Man With The Child In His Eyes A3 2:38 Producer – Andrew Powell Breathing A4 5:28 Producer – Jon Kelly, Kate Bush Wow A5 3:46 Producer – Andrew Powell Hounds Of Love A6 3:02 Producer – Kate Bush Running Up That Hill B1 5:00 Producer – Kate Bush Army Dreamers B2 3:13 Producer – Jon Kelly, Kate Bush Sat In Your Lap B3 3:29 Producer – Kate Bush Experiment IV B4 4:21 Producer – Kate Bush The Dreaming B5 4:14 Producer – Kate Bush Babooshka B6 3:29 Producer – Jon Kelly, Kate Bush Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI Records Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Novercia Ltd. Copyright (c) – Novercia Ltd. Licensed To – EMI Records Ltd. Published By – Kate Bush Music Ltd. Published By – EMI Music Publishing Ltd. Manufactured By – EMI-Valentim De Carvalho, Música Lda. Distributed By – EMI-Valentim De Carvalho, Música Lda. Credits Design – Bill Smith Studio Mastered By [Cut By] – Ian Cooper Other [Hair] – Anthony Yacomine Other [Make-up] – Sue Adams Photography By [Cover] – John Carder Bush Written-By – Kate Bush Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix -

Song Name Artist

Sheet1 Song Name Artist Somethin' Hot The Afghan Whigs Crazy The Afghan Whigs Uptown Again The Afghan Whigs Sweet Son Of A Bitch The Afghan Whigs 66 The Afghan Whigs Cito Soleil The Afghan Whigs John The Baptist The Afghan Whigs The Slide Song The Afghan Whigs Neglekted The Afghan Whigs Omerta The Afghan Whigs The Vampire Lanois The Afghan Whigs Saor/Free/News from Nowhere Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 1 Afro Celt Sound System Inion/Daughter Afro Celt Sound System Sure-As-Not/Sure-As-Knot Afro Celt Sound System Nu Cead Againn Dul Abhaile/We Cannot Go... Afro Celt Sound System Dark Moon, High Tide Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 2 Afro Celt Sound System House Of The Ancestors Afro Celt Sound System Eistigh Liomsa Sealad/Listen To Me/Saor Reprise Afro Celt Sound System Amor Verdadero Afro-Cuban All Stars Alto Songo Afro-Cuban All Stars Habana del Este Afro-Cuban All Stars A Toda Cuba le Gusta Afro-Cuban All Stars Fiesta de la Rumba Afro-Cuban All Stars Los Sitio' Asere Afro-Cuban All Stars Pío Mentiroso Afro-Cuban All Stars Maria Caracoles Afro-Cuban All Stars Clasiqueando con Rubén Afro-Cuban All Stars Elube Chango Afro-Cuban All Stars Two of Us Aimee Mann & Michael Penn Tired of Being Alone Al Green Call Me (Come Back Home) Al Green I'm Still in Love With You Al Green Here I Am (Come and Take Me) Al Green Love and Happiness Al Green Let's Stay Together Al Green I Can't Get Next to You Al Green You Ought to Be With Me Al Green Look What You Done for Me Al Green Let's Get Married Al Green Livin' for You [*] Al Green Sha-La-La -

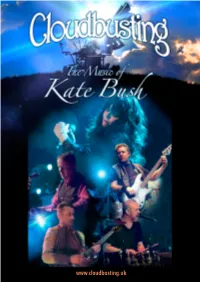

Cloudbusting - an Introduction to the Band: Page 3

Page 1 Contents: Cloudbusting - an introduction to the band: Page 3 Kate Bush - an enduring talent Page 4 Cloudbusting in Performance Page 5 The Tours Page 6 Live Stream events Page 7 The Band - Profiles Page 8-9 Social Media: Page 10 Marketing & Promotions: Page 11 Cloudbusting - The Music of Kate Bush The Show - tech spec, sound & lighting Page 12 Formed back in 2012, well before any suggestion that Kate Bush was ever going to perform live Box Office - useful info/Press release Page 13 again, Cloudbusting’s mission has always been to Agent: Page 14 bring Kate Bush’s music to the stage and perform the songs as faithfully to the original recordings as possible. The aim, to create an authentic live experience with all of the hits, as well as some of the less well known of Kate’s songs - some of which have never actually been heard played live before. ‘Running Up That Hill’, ‘Wuthering Heights’, ‘Hounds of Love,’ ‘Babooshka’, ‘This Woman’s Work’, ‘Wow’… Cloudbusting perform all the chart hits you’d expect to hear - so those who missed out on her live shows in 1979 and indeed 2014, will love the UK’s longest running and most universally applauded tribute act to Kate. Arguably, the band isn’t a ‘tribute’ in conventional terms, as no one is pretending to be Kate or impersonate her, instead the focus is on the authenticity of the music. Testament to this is that many of Kate’s original collaborators from both stage and the studio have been inspired to join the band for performances. -

Kate Bush, Un Destin "Aérien"…

KATE BUSH L’AERIENNE… "I'm a songwriter, not a personality and I find it difficult to talk about my songs sometimes. In a way, they speak for themselves and the subjects or inspirations can be so personal or just seem ridiculous when spoken about." (Kate Bush, KBC magazine, 1987) Auteur-compositeur-interprète de talent, Kate Bush est surtout connue pour sa voix fort expressive (qui couvre largement 4 octaves !), ses paroles de portée littéraire et/ou imaginaire ainsi que par son style musical aventureux et ses productions méticuleuses. Depuis ses débuts discographiques en 1978 (avec le hit "wuthering heights", qui resta numéro 1 dans les charts britanniques durant 4 semaines), elle compte un nombre considérable de fans fidèles de part le monde. Tout le monde (ou presque…) a déjà entendu au moins une fois "babooshka" ou "running up that hill", deux singles qui ont littéralement cassés la baraque à leur sortie. A l’occasion de son grand retour après douze ans d’absence (son dernier opus "The red shoes" date tout de même de 1993 !) et avec un double album de surcroît ("Aerial"), la rédaction du Koid’9 a pensé qu’il serait bon de vous faire réviser le "petit K.T. illustré" (Kate cache ce sigle – qui signifie littéralement en anglais Cathy - sur tous ses albums depuis le premier, le saviez-vous ?) et pourquoi pas, pour les plus chanceux d’entre vous, faire découvrir l’univers unique et magique de la belle Cathy. Vous découvrirez ainsi, outre une biographie la plus complète possible, sa discographie et vidéographie commentée, ses diverses collaborations musicales, les sites Internet majeurs la concernant et une intéressante monographie sur son univers de "femme étoile"… Permettez-moi donc de vous souhaiter chaleureusement la bienvenue dans un monde sensuel, féerique et envoûtant à la limite de l’étrange et du merveilleux… Un dossier amoureusement préparé par Renaud Oualid avec les aimables participations de Thierry de Fages, Cyrille Delanlssays, Marc Moingeon et Cousin Hub. -

The Kate Bush Mysteries: Fact Or Fiction?

Paper No. 1 THE KATE BUSH MYSTERIES: FACT OR FICTION? ©Robert Moore, 2009. http:// www.deltapro.co.uk/katebushm.pdf 3rd November 2009. (V3.3141) The author welcomes any commentary, further information or clarifications in relation to this article or related matters. Please note that Kate Bush greatly cherishes her privacy. Therefore the writer kindly asks readers to please respect this and not to use this article as a pretext to pester her! Please note this is an unofficial and independent article NOT endorsed or authorised by Kate Bush, her management or any agency associated with her. Nonetheless, every possible care has been taken in its research. Please send ANY questions re this item to me I will try and answer them as best I can. This article is not-for-profit and is circulated for research purposes only. Contact details: email: [email protected] 0 INTRODUCTION: Since her appearance on the popular music scene in 1978, the English singer-songwriter Kate Bush has been associated in the publicIntroduction. consciousness with a cornucopia of “new age” ideals. But where does media hype, fiction and wishful thinking end and the truth begin? This article examines these various claims, statements and interpretations in an attempt to determine whether these rumours and populist legends have any valid justification … Meet the Music Muse….. To begin at the beginning, this distinctive musical artist - actual name Catherine Bush - was born on the 30 th July 1958; her father being a General Practitioner, her mother a nurse originating from Ireland (who was reputedly psychic) (1) . Kate Bush was raised within a close, musical and artistic middle-class family, several members of which - most notably her two brothers Patrick and John - reportedly had an interest in various “countercultural” concepts (1). -

Youtube Nightstick

Iron Claw - Skullcrusher - 1970 - YouTube Damon -[1]- Song Of A Gypsy - YouTube Chromakey Dreamcoat - YouTube Nightstick - Dream of the Witches' Sabbath/Massacre of Innocence (Air Attack) - YouTube Nightstick - Four More Years - YouTube Orange Goblin - The Astral Project - YouTube Orange Goblin - Nuclear Guru - YouTube Skepticism - Sign of the Storm - YouTube Cavity - Chase - YouTube Supercollider - YouTube Satin Black - YouTube Today Is The Day - Willpower - 2 - My First Knife - YouTube Alex G - Gnaw - YouTube Stereo Total - Baby Revolution - YouTube Add N To (X) Metal Fingers In My Body - YouTube 'Samurai' by X priest X (Official) - YouTube Bachelorette - I Want to be Your Girlfriend (Bored to Death ending credits) - YouTube Bachelorette - Her Rotating Head (Official) - YouTube The Bug - 'Fuck a Bitch' ft. Death Grips - YouTube Stumble On Tapes - Girlpool - YouTube Joanna Gruesome - Talking To Yr Dick - YouTube Joanna Gruesome - Lemonade Grrl - YouTube BLACK DIRT OAK "Demon Directive" - YouTube Black Dirt Oak - From The Jaguar Priest - YouTube alternative tv how much longer - YouTube Earthless - Lost in the Cold Sun - YouTube Electric Moon - The Doomsday Machine (2011) [Full Album] - YouTube CWC Music Video Holding Out For a Hero - YouTube La Femme - Psycho Tropical Berlin (Full Album) - YouTube Reverend Alicia - YouTube The Phi Mu Washboard Band - Love Hurts - YouTube BJ SNOWDEN IN CANADA - YouTube j-walk - plastic face (prod. cat soup) - YouTube BABY KAELY "SNEAKERHEAD" AMAZING 9 YEAR OLD RAPPER - YouTube Bernard + Edith - Heartache -

WLIR Playlist

I believe this complete list of WLIR/WDRE songs originally appeared on this site, but the full playlist is no longer available. https://wlir.fm/ It now only has the list of “Screamers and Shrieks” of the week—these were songs voted on by listeners as the best new song of the week. I’ve included the chronological list of Screamers and Shrieks after the full alphabetical playlist by artist. 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Can't Ignore The Train 10,000 Maniacs Eat For Two 10,000 Maniacs Headstrong 10,000 Maniacs Hey Jack Kerouac 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Non-Live version) 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Live) 10,000 Maniacs Peace Train 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs What's The Matter Here 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 12 Drummers Drumming We'll Be The First Ones 2 NU This Is Ponderous 3D Nearer 4 Of Us Drag My Bad Name Down 9 Ways To Win Close To You 999 High Energy Plan 999 Homicide A Bigger Splash I Don’t Believe A Word (Innocent Bystanders) A Certain Ratio Life's A Scream A Flock Of Seagulls Heartbeat Like A Drum A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls It's Not Me Talking A Flock Of Seagulls Living In Heaven A Flock Of Seagulls Never Again (The Dancer) A Flock Of Seagulls Nightmares A Flock Of Seagulls Space Age Love Song A Flock Of Seagulls Telecommunication A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls What Am I Supposed To Do A Flock Of Seagulls Who's That Girl A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing A Popular History Of Signs The Ladderjack -

1984 Ladyslipper Cat and Resource Guide Ecords & Tapes by Women a Few Words About Ladyslipper

1984 Ladyslipper Cat and Resource Guide ecords & Tapes by Women A Few Words About Ladyslipper Ladyslipper is a North Carolina non-profit, tax- Culver, Alive!), Even Keel (Kay Gardner), Old Lady awards. Any conductor of a symphony or chamber exempt organization which has been involved in Blue Jeans (Linda Shear), Philo (Ferron), Biscuit orchestra interested in performing this piece many facets of women's music since 1976. Our City (Rosy's Bar & Grill), Origami (Betsy Rose & should contact Ladyslipper. basic purpose has consistently been to heighten Cathy Winter), Sweater (Jasmine), Mary Records Our name comes from an exquisite flower public awareness of the achievements of women (Mary Lou Williams), Whyscrack (Kate Clinton), which is one of the few wild orchids native to North artists and musicians and to expand the scope and Freedom's Music (Debbie Fier), Wild Patience America and is currently an endangered species. availability of musical and literary recordings by (Judy Reagan), Rebecca (anthology), Coyote Donations are tax-deductible, and we do need women. (Connie Kaldor), Mother of Pearl (Heather Bishop), the help of friends to continue to grow. We also are The most unique aspect of our work has been One Sky (Judy Gorman-Jacobs) and others. In seeking loans of at least $ 1000 for at least a year; if the annual publication of the world's most com most of these cases, all of the records at each you have some extra money and would like to prehensive Resource Guide and Catalog of Re pressing are shipped from the pressing plant to be invest it in a worthy endeavor, please write for more cords and Tapes by Women—the one you now warehoused at and shipped from Ladyslipper, and information. -

Record-Business-1981

4 INSIDE Singles chart 6-7; Album chart, 17; New Singles,19; New Albums, 16; Airplay guide, 14- 15; Small Labels,18; The Royal Wedding Discs, 5-8. JULY13,1981VOLUME THREE Number 16 '60p CBS dominates Deram scraps 'Or LP RB second after Southall riot quotes survey DECCA'SDERAM label has deletedmember of the National Front 'Leader IN THE wake of its massive hits with and withdrawn an 'Oi' music compila-Guard', although Deram has been un- Adam and the Ants and Star Sound, tion -a special co -promotion deal withable to confirm this. CBS predictably takes the top position consumer rock weekly Sounds - in the Said the label's marketing manager in every category, with the exception of wake of last weekend's riot in Southall.John Preston: "We utterly deplore and Indie Labels, in RB's survey of sales The album entitled Strength Throughcondemn the events of Friday night at activity through its panel shops in the Oi, featured material by skinhead groupSouthall. In order that there should be second quarter of the year. the 4 Skins, who were headlining theno confusion as to our attitude, it has Adam and the Ants top the lists of the Southall pub gig at the centre of lastbeen decided to delete the LP Strength top 30 best-selling singles and albums, Friday's racial violence. Through Oi. TEARDROP EXPLODES have beenwith Star Sound in third place on singles The LP was released earlier this year. "While we do not feel that the albumso busy on the road of late that it wasand runner-up on albums, as well as It was compiled by Sounds journalists,is a major part of the overall problem, itonly last week that singer Julian Copetopping the disco/soul top sellers. -

21/8/14 Slagg Brothers Rhythm & Blues, Soul

21/8/14 Slagg Brothers Rhythm & Blues, Soul & Grooves Show Early Morning Blues 2:04 Boogie Jake Jacobs 1959. Backslop 2:33 Baby Earl & The Trinidads 1960 (Kiss me a lot). Written in 1940 by Mexican songwriter Consuelo Velázquez, Besame Mucho (Part 1) 2:19 The Coasters recognized as the most sung and recorded Mexican song in the world. Do It Again 2:20 The Beach Boys 1968, written by Brian Wilson and Mike Love, who also share lead vocals. Originally released in the US on the Veep label in 1966. Gained popularity on the Better Use Your Head 2:52 Little Anthony & The Imperials Northern soul scene in the UK. It made number 42 in the UK charts in 1976. 1987, from Bring the Family, his eighth album. It features Ry Cooder on guitar, Nick Memphis In The Meantime 4:00 John Hiatt Lowe on bass guitar and Jim Keltner on drums. He sang preaching type songs under the name of "Luke the Drifter," - an idealized Ramblin' Man (Luke The 3:00 Hank Williams character who went across the country preaching the gospel, and doing good deeds Drifter) while Hank Williams, the drunkard who cheated on women He has been called the Nat King Cole of Jamaica. He wrote both "Keep On Running" I Feel So Bad 2:03 Jackie Edwards and "Somebody Help Me", that became no1 singles in the UK for The Spencer Davis Group Bouncing Woman 2:34 Laurel Aitken 1961 on Blue Beat. 1974, from their album Band on the Run. The song peaked at number 7. -

Music 334 2011

WOMEN, MUSIC AND GENDER — MUSIC 334 Conrad Grebel College, University of Waterloo Dr. Carol Ann Weaver, Professor Monday Evenings, 7-10 PM, Room 1302, CGC, Fall, 2011 WEEK AREAS OF STUDY Soundfiles Readings* (*note: required readings are shown by asterick* and by bold font; other readings are optional but recommended, either on reserve in the Conrad Grebel Library (top floor of Grebel academic building) or on ACE site as reading files. Sound files must be accessed via UW ACE for the course Music 334) Playlists Readings 1, Sept. 12 Introduction. Overview of women’s roles in music throughout 1 *Pendle Ch.1 history and within several specific non-Western, traditional Drinker, societies. Readings in Western philosophies dealing Ch. 1-9; with expected roles of women in society will be included. Stone, “Gifts Roles of women in the musical & religious areas of ancient from Reclaiming” and traditional societies — social contexts will be dealt with in Zweig: To Be historically, emphasizing cultural settings in which women are a Woman, pp. 203-216 most likely to make musical contributions. The earlier, more "traditional" societies are more likely for women to be prominent leaders within ritual/religious realms. Music in Ancient Societies l. Middle East, 25,000 B.C. 7. China, 500 B.C. 2. Near East, 9,000-7,000 B.C. 8. India, 500 B.C 3. Egypt, 4,000 B.C. 9. Israel, l,800-00 B.C. 4. Babylon, 4,000 B.C. 10. traditional African--ancient to 20th C. 5. Crete, 4,000-2,000 B.C. 11. traditional North American Native 6.