I THAT BRIGHT & BEAUTIFUL DAY by Martin Wiley a Thesis Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Guitar Songbook Series

feature guitar songbook series 1465 Alfred Easy Guitar Play-Along 1484 Beginning Solo Guitar 1504 The Book Series 1480 Boss E-Band Guitar Play-Along 1494 The Decade Series 1464 Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series 1483 Easy Rhythm Guitar Series 1480 Fender G-Dec 3 Play-Along 1497 Giant Guitar Tab Collections 1510 Gig Guides 1495 Guitar Bible Series 1493 Guitar Cheat Sheets 1485 Guitar Chord Songbooks 1494 Guitar Decade Series 1478 Guitar Play-Along DVDs 1511 Guitar Songbooks By Notation 1498 Guitar Tab White Pages 1499 Legendary Guitar Series 1501 Little Black Books 1466 Hal Leonard Guitar Play-Along® 1502 Multiformat Collection 1481 Play Guitar with… 1484 Popular Guitar Hits 1497 Sheet Music 1503 Solo Guitar Library 1500 Tab+: Tab. Tone. Technique 1506 Transcribed Scores 1482 Ultimate Guitar Play-Along Please see the Mixed Folios section of this catalog for more2015 guitar collections. 1464 EASY GUITAR PLAY-ALONG® SERIES The Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series features 9. ROCK streamlined transcriptions of your favorite SONGS FOR songs. Just follow the tab, listen to the CD or BEGINNERS Beautiful Day • Buddy Holly online audio to hear how the guitar should • Everybody Hurts • In sound, and then play along using the back- Bloom • Otherside • The ing tracks. The CD is playable on any CD Rock Show • Use Somebody. player, and is also enhanced to include the Amazing Slowdowner technology so MAC and PC users can adjust the recording to ______00103255 Book/CD Pack .................$14.99 any tempo without changing the pitch! 10. GREEN DAY Basket Case • Boulevard of Broken Dreams • Good 1. -

SINGALONG SONG LIST 5 Pm PST / 8 Pm EST

Thursday, April 22 SINGALONG SONG LIST 5 pm PST / 8 pm EST Email [email protected] to reserve your song and your spot on the lineup! Beatles - Come Together, Something, Yesterday, Nowhere Man, I'm Elvis Presley - Suspicious Minds Looking Through You, In My Life, A Day in the Life, Hey Jude, I Will Eve 6 - Inside Out Billy Joel - Piano Man, Only the Good Die Young, just the way you are Everclear - Santa Monica The Black Crowes - She Talks To AngelsBlind Melon- No Rain Fleetwood Mac - Dreams, Gold Dust, Woman, Silver Springs Blur - Song #2 Foo Fighters - Everlong, Times Like These Brandi Carlile - the eye, Joesphine The Foundations - Butter cup Bryan Adams - Summer of '69 Fountains of Wayne - Stacy's Mom The Cars - Just What I Needed, You're All I've Got Tonight Freedy Johnston - Bad Reputation Cheap Trick - Surrender, I Want You To Want Me Green Day - Basketcase, Time of Your Life, Longview, Blvd of Broken The Church - Under the Milky Way Tonight Dreams Coldplay - Yellow, The Scientist, Guns and Roses - Patience, Don't Cry Counting Crowes - Mr. Jones, Long December Jane's Addiction - Jane Says Cracker - Low Jason Mraz - I'm Yours Crosby Stills and Nash - Teach Your Children Well Jeff Buckley - Hallellujah Dave Matthews Band - Crash Into Me, John Mayer - Who says i can’t get stoned, Say, Heartbreak Warfare David Bowie - Ziggy Stardust, Space Oddity, man who sold the world Johnny Cash - Folsom Prison Blues, Ring of Fire Death Cab for Cutie - I Will Follow You Into the Dark Kelly Clarkson - Since U Been Gone Elliot Smith - say yes The Killers - All These Things I've Done, Mr. -

Whitesnake (From the 1989 Album SLIP of the TONGUE) Transcribed by Californiahamer Words and Music by David Coverdale

FOOL FOR YOUR LOVING As recorded by Whitesnake (From the 1989 Album SLIP OF THE TONGUE) Transcribed by CaliforniaHamer Words and Music by David Coverdale Am11 G5 Am7 C5 D5 Dm7 Em7 F5 Em E5 Cmaj7/E A5 x 3 fr. xxxx 3 fr. xx 5 fr. x xxx 3 fr. x xxx 5 fr. x x 5 fr. x x 7 fr. xxx xxx 7 fr. x x 5 fr. x xx A Intro Moderate Rock = 120 Am11 P G5 Am7 C5 D5 G5 V V 1 U U U V V V I 4 Gtr I let ring T 8 (8) (8) (8) 8 15 13 A B sl. c 4 j k c V V V V V V V V c I 4 V V V V V V V V V V V V u V V Gtr II P.M. P.M. T 5 7 5 5 5 7 A 5 7 5 5 5 7 B 5 7 0 0 5 3 5 3 sl. sl. Am7 C5 G5 Am7 C5 D5 G5 5 U V V V U I V V V V V tr [[[ T 14 14 12 A 12 14 (14) 12 10 9 (10) 7 B sl. sl. sl. c c V V V V V V k c c V V V V V V V V c I V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V u V V V V V u V V P.M. -

Thanks for Coming out Tonight. Look Over the List and Let Me Know What You’D Like to Hear

Thanks for coming out tonight. Look over the list and let me know what you’d like to hear. Above all else . Have a good time! I also write a lot of music. My songs are listed first on the list and are in red. CD’s are $10. Enjoy. --- Domenick Domenick Swentosky Times they are A-Changin’ --(My Original Songs)-- All Along the Watchtower Dire Staits The Great Divide Shelter from the Storm Romeo and Juliet Liar Bob Marley Dispatch Walking Bob Dylan Redemption Song The General Goodbye Goldie Bobby McFerrin Don Maclean Afterlife Don’t Worry, Be Happy American Pie Grandfather Bob Seger The Doors Louisiana Poor Turn the Page Love Me Two Times Never Leave Against the Wind The Eagles Here Bon Jovi Take It Easy Haunted Dead or Alive Elton John Downtown Bowling For Soup Daniel Ever Be Come Back to Texas Tiny Dancer Saturday Brian Adams Rocketman Joyride Summer of ‘69 Levon Runnin’ Free Bright Eyes Elvis Presley Good Enough First Day of My Life Return to Sender Discover Bruce Hornsby Eric Clapton Six Strings The Way It Is San Francisco Bay Blues Come On Around Buffalo Springfield Layla The Last Time For What It’s Worth Everlast Storm Inside the Calm Bush What It’s Like Hideaway Machinehead Fall Out Boy The Postage Glycerine Sugar We’re Going Down The Simple Life Cat Stevens Five For Fighting Aerosmith Wild World America Town FINE First Cut is the Deepest Fleetwood Mac Alan Jackson CCR Landslide 5:00 Somewhere Have You Ever Seen the Rain Foo Fighters Alien Ant Farm Bad Moon Rising Learn To Fly Smooth Criminal The Clarks Everlong Allman Brothers Born -

October 19Th 1994

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Coyote Chronicle (1984-) Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 10-19-1994 October 19th 1994 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle Recommended Citation CSUSB, "October 19th 1994" (1994). Coyote Chronicle (1984-). 364. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle/364 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coyote Chronicle (1984-) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural CSUSB Development Update: awareness Expansion progresses rapidly heightened at Jeremy Heckler along with a self-instructional video mons. and gymnasium for earth and offices. CSUSB Columnist and photographic studio. It will also quake retrofitting. Vice President Funding fcM* these projects comes Construction crews have been include a self-instructional computer of Finance, David DeMauro said from two types of bwd measures. General obligation bonds, such as Kathy Carey busy this year as three projects are graphic studio, with a two-story ad that due to lack of funding, new buildings may be required to do Proposition IC, are approved by Chronicle Staff Writer currently underway. The Health & ministration wing. Physical Education Complex, the Development of new buildings double-duty serving other depart the voters and are paid back by the at CSUSB have been put into mo ments. DeMauro also stated that state. Other funding comes from The multicultural center was Visual Arts building and the Ex tion, using the Five-Year Capital current projects are not to meet the revenue bonds that are approved by introduced to CSUSB last year and tended Education complex are in different phases of construction, Improvement Program. -

The Hal Leonard Guitar Play-Along® Series Will Assist Players in Learning

1. Rock 6. ’90s Rock Day Tripper • Message in a Are You Gonna Go My Way • Bottle • Refugee • Shattered Come Out and Play • I’ll Stick • Sunshine of Your Love • Around • Know Your Enemy • Takin’ Care of Business • Man in the Box • Outshined • Tush • Walk This Way. Smells like Teen Spirit • Un- 00699570 �������������� $16.99 der the Bridge. 00699572 �������������� $16.99 2. Acoustic 7. Blues Angie • Behind Blue Eyes • All Your Love (I Miss Loving) Best of My Love • Blackbird • Born Under a Bad Sign • • Dust in the Wind • Layla • Crosscut Saw • I’m Tore Night Moves • Yesterday. Down • Pride and Joy • The 00699569 �������������� $16.95 Sky Is Crying • Sweet Home Chicago • The Thrill Is Gone. The Hal Leonard Guitar Play-Along® 00699575 �������������� $16.95 Series will assist players in learning to play their favorite songs quickly and 3. Hard Rock 8. Rock easily. Just follow the tab, listen to Crazy Train • Iron Man • Liv- All Right Now • Black Magic the CD to hear how the guitar should ing After Midnight • Rock You Woman • Get Back • Hey Joe sound, and then play along using the like a Hurricane • Round and • Layla • Love Me Two Times Round • Smoke on the Water • Won’t Get Fooled Again • separate backing tracks. Mac and PC • Sweet Child O’ Mine • You You Really Got Me. users can also slow down the tempo Really Got Me. 00699585 �������������� $12.95 – without changing pitch! – by using 00699573 �������������� $16.95 the CD in their computer. The melody and lyrics are also included in the book 4. Pop/Rock 9. -

The Piano Man's Keyboard Man

" (https://www.facebook.com/musicplayersofficial/?ref=search) # (https://twitter.com/musicplayersnow) $ (https://www.instagram.com/musicplayersofficial/) (https://musicplayers.com) (https://servedbyadbutler.com/redirect.spark? MID=149702&plid=520994&setID=89485&channelID=0&CID=0&banID=519383934&PID=0&textadID=0&tc=1&mt=1581972831381656&sw=1440&sh=900&spr=2&hc=bc56a74695c43437f5f7556e370cd5ba58593a61&location=) (https://servedbyadbutler.com/redirect.spark? MID=149702&plid=520997&setID=89485&channelID=0&CID=0&banID=519383938&PID=0&textadID=0&tc=1&mt=1581972809883731&sw=1440&sh=900&spr=2&hc=fe20a6f92afa98349142bd6b15c09a8bb4e68c65&location=) % & ! Home (https://musicplayers.com/) › Feature Stories (https://musicplayers.com/category/feature-stories- 2/) › David Rosenthal: The Piano Man's Keyboard Man DAVID ROSENTHAL: THE PIANO MAN'S KEYBOARD MAN FEATURE STORIES (HTTPS://MUSICPLAYERS.COM/CATEGORY/FEATURE-STORIES-2/), KEYBOARD PLAYER FS (HTTPS://MUSICPLAYERS.COM/CATEGORY/FEATURE-STORIES-2/KEYBOARD-PLAYERS/) / NOVEMBER 6, 2017 / BY SCOTT KAHN (HTTPS://MUSICPLAYERS.COM/AUTHOR/SCOTTK/) JASON BUCHWALD (HTTPS://MUSICPLAYERS.COM/AUTHOR/JASONB/) Grammy-nominated keyboard player, David Rosenthal, is no ordinary musician. He’s an unsung hero' of the keyboard world, currently serving as musical director for Billy Joel’s band, which he has been a part of since 1993. This role is just one small part of his exciting history, though. Yes, he backs up the piano man nightly and is in fact one of only three other people to ever play a recorded piano part on a Billy Joel record (the others being Ray Charles and Richard Tee). But Rosenthal already had a pretty impressive resume by the time Billy Joel came calling. Rosenthal attended Berklee College of Music, where he became a then-bandmate and lifelong friend of fellow classmate, Steve Vai. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

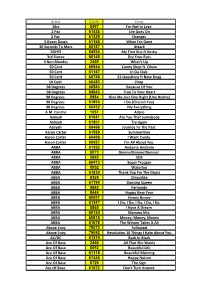

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam -

|||GET||| the White Snake a Play 1St Edition

THE WHITE SNAKE A PLAY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Mary Zimmerman | 9780810129276 | | | | | Whitesnake Starkers in Tokyo Live Open Preview See a Problem? The weekend before she's supposed to start school at the recently integrated Mason High in Bakersfield, Alabama, a fatal car accident threatens the fragile peace her town has experienced To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. It is also told through a "branching" narrative that attempts to present a composite of several versions of the same myth. MiddlesbroughClevelandEngland. Add to Wishlist. In Septemberthe band announced that their next album was set for a tentative spring release. Which is it? Javascript is not enabled in your browser. In her latest theatrical production inspired by a classic story, Mary Zimmerman reimagines The White Snake, an ancient Chinese legend in which a snake spirit transforms herself into a beautiful woman in order to experience the human world. The band's self-titled album was their most commercially successful worldwide, and contained two major US hits, " Here I Go Again " and " Is This Love ", reaching number one and two on the Billboard Hot We must shift for ourselves, and yet we cannot fly! Du Bois and other remarkable Judith Bridges rated it it was amazing Jan 01, Inheritors of the Spirit Premier in American civil rights history stands the National Association for Maggie rated it liked it Apr 10, Learn how to enable JavaScript The White Snake A Play 1st edition your browser. Welcome back. Snakebite Long Way from Home Versions. Chad rated it The White Snake A Play 1st edition it Jun 02, Classic Rock That stupid horse, with his heavy hoofs, has been treading down my people without mercy! Learn about this Leonard family with maps, news clippings, census records, But when the proud princess perceived that he was not her equal in birth, she scorned him, and required him first to perform another task. -

The U */ Latest and T Greatest on Your Favorite the Addictions PAGES 10 -12 UWM

MaKXabicMMWHMMM Sequels to Lego Star Wars and Post Editorial weighs in on Kgep cozy and save Guitar Hero, plus Nintendo Wii midterm election results money doing it preview - PAGES 20,21 PAGE 8 Post A&E has the U */ latest and t greatest on your favorite The addictions PAGES 10 -12 UWM November 13,2006 The student-run independent newsweekiy • Since 1956 Volume 511 Issue 11 58 ballots left Senate uncounted at searches for Sandburg Hall common voting location ground Some voters find Separation of Powers 'Green Room' Act voted down misleading By Ryan Cardarella Campus Government Editor By Stephanie Brien City Editor The Student Association Senate meeting was decidedly less cha After running out of ballots in otic Sunday night, with healthy the University of Wisconsin-Mil debate taking the place of the waukee Sandburg Hall Ward 40 bitter division within the Senate voting location, 58 ballot copies that concluded with a walkout have not been counted for the two weeks ago. Nov. 7 election results, election officials said. When the ballots ran out, the "We can choose to get poll workers had to make copies bogged down with internal of the original for the last voters. But the ballots were unable to go issues or we can come through the machine and were and do the jobs we were not counted in the machine's to tal, which was reported to the elected to do." Election Commission. - Samantha Prahl, Student Ward 40, which includes streets west of campus to the Association president river from Kenwood to Edge- wood, reported 1,132 cast votes "We can choose to get bogged to the Election Commission. -

![Wilfrid Barbrooke Grubb [1865-1930], a Church in the Wilds. the Remarkable Story of the Establishment](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6051/wilfrid-barbrooke-grubb-1865-1930-a-church-in-the-wilds-the-remarkable-story-of-the-establishment-5966051.webp)

Wilfrid Barbrooke Grubb [1865-1930], a Church in the Wilds. the Remarkable Story of the Establishment

TYPICAL MASCOY WOMAN AND CHILD They belong to a clau living north of the Rio Verde. The palm-log hut is one of the improved Ind ian b uildings. The tablecloth ~nd jug indicate the social advance. A CHURCH IN THE WILDS THE REMARKABLE STORY OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN MISSION AMONGST THE HITHERTO SAVAGE AND INTRACTABLE NATIVES OF THE PARAGUAYAN CHACO BY W. BARBROOKE GRUBB "COMISARIO GltNl:RAL DEL CHACO Y- PACIFICADOR DE LOS INDIOS tt PIONEER fE! EXPLORER OF THE CHACO AUTHOR OJ' "AN UNKNOWN PEOPLE. IN AN UNICNOWN LAND'' EDITED BY H. T. MORREY JONES, M.A. (OxoN} WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS Is 2 MAPS LONDON SEELEY, SERVICE & CO. LIMITED 196 SHAFTESBURY AVENUE 1925 Printed in Great Britain. TO MY MOTHER THIS BOOK IS Al<'FECTIONATELY DEDICATED THE DARK PART SHOWS THE Al1EA OF THE CHACO COMPARED WITH THll: CONTINENT OF SOUTH AMERICA. op<1i So,hi/r 511 J<ISAPANG Na Atl,/a,ranca/r 0 ....__ --· 23 23 Yitliwase-Yamliiyit < 24 SCALE-about 60 Miles to an Inch 59 58 EL GRAN CHACO. CONTENTS PART I CHAPTER I A UNIQUE FIELD P.A.Gl!lB Difficult problems-An unexplored country-A unique situation -The Chaco and its people-Decline of population-Work- ing under difficulties-Languages of the tribes - 19-24 CHAPTER II A RIVER BASE Ignorance of m1ss10n work-The first settlement-Death of a pioneer-A rapacious chief-A perilous undertaking-Well- nigh hopeless - - - - - - 25-29 CHAPTER III "BURNING MY BOATS" A bold step-Tracking the thieves-Native criticism-Taking a high hand-Deserted---;-Reconciliation-Narrow escapes- Privations-A visitor-Solitude-Pioneering