ˇ Lea Wierød Borcak the Sound of Nonsense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fragile, Emergent, and Absent Tonics in Pop and Rock Songs *

Fragile, Emergent, and Absent Tonics in Pop and Rock Songs * Mark Spicer NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: h'p://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.17.23..(mto.17.23.2.spicer.php 0E1WORDS: tonality, popular song, rock harmony, ragile tonics, emergent tonics, absent tonics, soul dominant, Sisyphus e3ect A4STRACT: This article explores the sometimes tricky 6uestion o tonality in pop and rock songs by positing three tonal scenarios: 1) songs with a fragile tonic, in which the tonic chord is present but its hierarchical status is weakened, either by relegating the tonic to a more unstable chord in 7rst or second inversion or by positioning the tonic mid-phrase rather than at structural points o departure or arrival8 .) songs with an emergent tonic, in which the tonic chord is initially absent yet deliberately saved or a triumphant arrival later in the song, usually at the onset o the chorus8 and 3) songs with an absent tonic, an extreme case in which the promised tonic chord never actually materiali9es. In each o these scenarios, the composer’s toying with tonality and listeners’ expectations may be considered hermeneutically as a means o enriching the song’s overall message. Close analyses o songs with ragile, emergent, and absent tonics are o3ered, drawing representative examples rom a wide range o styles and genres across the past 7 ty years o popular music, including 1960s Motown, 1970s soul, 1980s synthpop, 1990s alternative rock, and recent A.S. and A.0. B1 hits. Received November 2016 Colume 23, Number 2, Dune 2017 Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory F,G Skilled nineteenth-century song composers such as Robert Schumann and Dohannes 4rahms o ten exploited tonality and its expectations or symbolic or expressive purposes. -

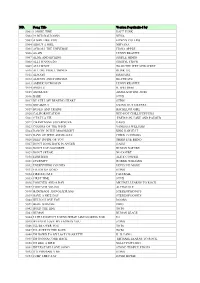

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Uptownlive.Song List Copy.Pages

Uptown Live Sample - Song List Top 40/ Pop 24k Gold - Bruno Mars Adventure of A Lifetime - Coldplay Aint My Fault - Zara Larsson All of Me (John Legend) Another You - Armin Van Buren Bad Romance -Lady Gaga Better Together -Jack Johnson Blame - Calvin Harris Blurred Lines -Robin Thicke Body Moves - DNCE Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Cake By The Ocean - DNCE California Girls - Katy Perry Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen Can’t Feel My Face - The Weeknd Can’t Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Cheap Thrills - Sia Cheerleader - OMI Clarity - Zedd feat. Foxes Closer - Chainsmokers Closer – Ne-Yo Cold Water - Major Lazer feat. Beiber Crazy - Cee Lo Crazy In Love - Beyoncé Despacito - Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee and Beiber DJ Got Us Falling In Love Again - Usher Don’t Know Why - Norah Jones Don’t Let Me Down - Chainsmokers Don’t Wanna Know - Maroon 5 Don’t You Worry Child - Sweedish House Mafia Dynamite - Taio Cruz Edge of Glory - Lady Gaga ET - Katy Perry Everything - Michael Bublé Feel So Close - Calvin Harris Firework - Katy Perry Forget You - Cee Lo FUN- Pitbull/Chris Brown Get Lucky - Daft Punk Girlfriend – Justin Bieber Grow Old With You - Adam Sandler Happy – Pharrel Hey Soul Sister – Train Hideaway - Kiesza Home - Michael Bublé Hot In Here- Nelly Hot n Cold - Katy Perry How Deep Is Your Love - Calvin Harris I Feel It Coming - The Weeknd I Gotta Feelin’ - Black Eyed Peas I Kissed A Girl - Katy Perry I Knew You Were Trouble - Taylor Swift I Want You To Know - Zedd feat. Selena Gomez I’ll Be - Edwin McCain I’m Yours - Jason Mraz In The Name of Love - Martin Garrix Into You - Ariana Grande It Aint Me - Kygo and Selena Gomez Jealous - Nick Jonas Just Dance - Lady Gaga Kids - OneRepublic Last Friday Night - Katy Perry Lean On - Major Lazer feat. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

10 Cc 10000 Maniacs 2 Unlimited 3 Doors Down

10 CC ALL SAINTS I'm not in love 6127 I know where it's at 2797 10000 MANIACS never ever 2794 more than this 2898 ALL-4-ONE 2 UNLIMITED I swear 2888 No limit 6067 ALPHAVILLE 3 DOORS DOWN Forever young 6076 when i'm gone 2849 AMERICA 4 NON BLONDES a horse with no name 2595 What's going on 6121 Razorlight 3506 5 Seconds of Summer AMY GRANT Yougblood 4525 take a little time 2900 98 DEGREES AMY WINEHOUSE give me just one night 2825 Rehab 6402 AALIYAH ANDREAS JOHNSON are you that somebody 2925 Glorious 3508 ABBA ANDREW SISTERS dancing queen 2138 boogie woogie bugle boy 2321 does your mother know 2144 ANDY WILLIAMS fernando 2141 moon river 2562 gimme ! gimme ! gimme ! 2143 Anna Kendrick I do, i do, i do, i do, i do 2142 Cups (Pich Perfect "When I'm gone") 4412 I have dream 2145 Anne Marie knowing me, knowing you 2133 2002 4527 s.o.s 2136 Perfect to me 4528 take a chance on me 2140 AQUA thank you for the music 2137 barbie girl 2681 the winner take it all 2132 ARETHA FRANKLIN waterloo 2139 respect 2583 ABBA TRIBUTE Say a little prayer 6074 Thank ABBA for the music 3640 Ariana Grande ACDC 7 rings 4530 Highway to hell 6059 Almost Is Never Enough 4070 ACE OF BASE Bad idea 4531 living in danger 2508 Better off 4532 Adele Break Free 4071 Hello 4320 Break up with your girlfriend 4533 Hello 4200 Breathin 4534 Make you feel my love 3708 Everytime 4535 Rolling in Deep 3504 God is a woman 4536 Set the fire to the rain 3706 Imagine 4537 Someone like you 3707 Just A Little Bit Of Your Heart 4072 When we were young 4201 Love Me Harder 4073 AGNES Monopoly 4541 Release me 6401 NASA 4538 A-HA Needy 4529 take on me 2299 No tears left to cry 4539 Alan Walker Positions 4741 Faded 4203 Problem (feat. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

The Revels Repertoire

THE REVELS REPERTOIRE POP Ain’t It Fun – Paramore Don’t StoP the Music – Rihanna All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Dynamite – Taio Cruz American Boy – Estelle Everybody – Backstreet Boys Animal – Neon Trees Everybody Talks – Neon Trees Baby I Love Your Way – Big Mountain, Tom Exs and Ohs – Elle King Lord-Alge Firework – Katy Perry Back to Black – Amy Winehouse Forever – Chris Brown Bad Guy – Billie Eilish Forget You – CeeLo Green Bad Romance – Lady Gaga Feels – Calvin Harris, Pharrell Williams, Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Katy Perry Minaj Feel It Coming – The Weeknd Believe – Cher Feel It Still – Portugal. The Man Best Day of My Life – American Authors Get Lucky – Daft Punk Born This Way – Lady Gaga Get the Party Started – P!nk Bye Bye Bye – *NSYNC Give Me Everything – Ne-yo and Pitbull Cake by the Ocean – DNCE Good as Hell – Lizzo California Gurls – Katy Perry HaPPy – Pharrel Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae JePsen Havana – Camila Cabello Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Heaven – Los Lonely Boys Can’t StoP the Feeling – Justin Timberlake Hey Soul Sister – Train Candyman – Christina Aguilera High Horse – Kacey Musgraves Chandelier – Sia Ho Hey – The Lumineers CheaP Thrills – Sia Hold My Hand – Jess Glynne Cheerleader – OMI Holiday – Madonna Closer – The Chainsmokers I Don’t Like It, I Love It – Flo Rida and Robin Counting Stars – OneRePublic Thicke Crazy – Gnarls Barkley I Kissed a Girl – Katy Perry CreeP – TLC I Love It – Icona PoP Cruel Summer – Bananarama I Love You Always Forever – Donna Lewis Dancing on My Own – Robyn Into You – Ariana Grande Dear Future Husband – Meghan Trainor I Will Wait – Mumford & Sons Déjà Vu – Beyonce Ice Ice Baby – Vanilla Ice Domino – Jessie J Juice – Lizzo 1 Just Dance – Lady Gaga ShaPe of You – Ed Sheeran Just Fine – Mary J. -

POP Vol 1 Song List

NO. Song Title Version Popularized by 5001 1 MORE TIME DAFT FUNK 5002 99 RED BALLOONS NENA 5003 A GIRL LIKE YOU EDWYN COLLINS 5004 ABOUT A GIRL NIRVANA 5005 ACROSS THE UNIVERSE FIONA APPLE 5006 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ 5007 ALIVE AND KICKING SIMPLE MINDS 5008 ALL I WANNA DO SHERYL CROW 5009 ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET 5010 ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 5011 ALWAYS ERASURE 5012 ALWAYS AND FOREVER HEATWAVE 5013 AMERICAN WOMAN LENNY KRAVITZ 5014 ANGELS R. WILLIMAS 5015 ANTMUSIC ADAM AND THE ANTS 5016 BABE STYX 5017 BE STILL MY BEATING HEART STING 5018 BREAKOUT SWING OUT SISTERS 5019 BUSES AND TRAINS BACHELOR GIRL 5020 CALIFORNICATION RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS 5021 C’EST LA VIE EMERSON, LAKE AND PALMER 5022 CHAMPAGNE SUPERNOVA OASIS 5023 COLORS OF THE WIND VANESSA WILLIAMS 5024 DANCIN’ IN THE MOONLIGHT KING HARVEST 5025 DAYS OF WINE AND ROSES CHRIS CONNORS 5026 DEEP INSIDE OF YOU THIRD EYE BLIND 5027 DON’T LOOK BACK IN ANGER OASIS 5028 DON’T SAY GOODBYE HUMAN NATURE 5029 DON’T SPEAK NO DOUBT 5030 EIGHTEEN ALICE COOPER 5031 ETERNITY ROBBIE WILLIAMS 5032 EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE 5033 FIELDS OF GOLD STING 5034 FIRE ESCAPE FASTBALL 5035 FIRST TIME STYX 5036 FOREVER AND A DAY MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK 5037 FOREVER YOUNG ALPHAVILLE 5038 HANDBAGS AND GLADRAGS STEREOPHONICS 5039 HAVE A NICE DAY STEREOPHONICS 5040 HELLO I LOVE YOU DOORS 5041 HERE WITH ME DIDO 5042 HOLD THE LINE TOTO 5043 HUMAN HUMAN LEAGE 5044 I STILL HAVEN’T FOUND WHAT I AM LOOKING FOR U2 5045 IF I EVER LOSE MY FAITH IN YOU STING 5046 I’LL BE OVER YOU TOTO 5047 I’LL SUPPLY THE LOVE TOTO 5048 I’M DOWN TO MY LAST CIGARETTE K.