Aviation Safety World, November 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business & Commercial Aviation

BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION LEONARDO AW609 PERFORMANCE PLATEAUS OCEANIC APRIL 2020 $10.00 AviationWeek.com/BCA Business & Commercial Aviation AIRCRAFT UPDATE Leonardo AW609 Bringing tiltrotor technology to civil aviation FUEL PLANNING ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Part 91 Department Inspections Is It Airworthy? Oceanic Fuel Planning Who Says It’s Ready? APRIL 2020 VOL. 116 NO. 4 Performance Plateaus Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's) Derek Saunders

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 51 | Issue 1 Article 5 1985 The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's) Derek Saunders Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Derek Saunders, The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's), 51 J. Air L. & Com. 157 (1985) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol51/iss1/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE ANTITRUST IMPLICATIONS OF COMPUTER RESERVATIONS SYSTEMS (CRS's) DEREK SAUNDERS THE PASSAGE of the Airline Deregulation Act' dramat- ically altered the airline industry. Market forces, rather than government agencies, 2 began to regulate the indus- try. The transition, however, has not been an easy one. Procedures and relationships well suited to a regulated in- dustry are now viewed as outdated, onerous, and even anticompetitive. The current conflict over carrier-owned computer res- ervation systems (CRS's) represents one instance of these problems.3 The air transportation distribution system re- lies heavily on the use of CRS's, particularly since deregu- lation and the resulting increase in airline activity. 4 One I Pub. L. No. 95-504, 92 Stat. 1705 (codified at 49 U.S.C.A. § 1401 (Supp. 1984)). 2 Competitive Market Investigation, CAB Docket 36,595 (Dec. 16, 1982) at 3. For a discussion of deregulation in general and antitrust problems specifically, see Beane, The Antitrust Implications of Airline Deregulation, 45 J. -

Credit Travel Rewards Catalog Available, You Will Be Advised to Make an Alternate Selection Or May Return Your Points to Your Account

ScoreCard® Bonus Point Program Rules 4) Reservations shall also be subject to airline availability for advance gift shop purchases, gambling, beauty salon/barber shop/spa services, 1. As provided in these rules (“Rules”), account holders (“You” or “you”) earn (1) Point in the ScoreCard® fare category seating , non-refundable type tickets for the travel dates laundry, photographs, email, internet and fax, etc.) are the responsibility Program (“Program”) for every dollar in qualifying purchases that you: (i) charge to an eligible credit card specified. 5) ScoreCard travel services reserves the right to choose the of the Cardholder. 4) Cruises are non-refundable, non-cancelable and non- account covered by the Program (“Account”); and (ii) that appears on your statement during the Program Period. Purchases that are returned do not qualify for Points. No Points are earned for finance charges, fees, airline and routing on which to reserve and ticket Cardholders. transferable. Once redeemed, Bonus Points may not be added back to your cash advances, convenience checks, ATM withdrawals, foreign transaction currency conversion charges or ScoreCard account. 5) Please check with ScoreCard travel representatives Universal First Class/Business Class Ticket insurance charges posted to your account. Contact your financial institution (“Sponsor”) for full details on the Item Points Item # Item Points Item # for any documentation requirements or other restrictions associated Program Period dates during which you are eligible to earn Points. Cardholder is responsible for any overages above the maximum ticket with cruises. It is the guest’s responsibility to obtain appropriate 2. Points can be used to order the merchandise/travel awards (“Award(s)”) available in the current Program. -

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA Developer Administration Guide August 2014 W Q2 © 2012-2014, Sabre Inc. All rights reserved. This documentation is the confidential and proprietary intellectual property of Sabre. Any unauthorized use, reproduction, preparation of derivative works, performance, or display of this document, or software represented by this document, without the express written permission of Sabre Inc. is strictly prohibited. Sabre and the Sabre logo design and Sabre Travel Network and the Sabre Travel Network logo design are trademarks and/or service marks of an affiliate of Sabre. All other trademarks, service marks, and trade names are owned by their respective companies. DOCUMENT REVISION INFORMATION The following information is to be included with all versions of the document. Project Project Name Number Prepared by Date Prepared Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. • • • Table of Contents 1 Getting Started 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Summary of Changes .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 About This Guide ........................................................................................................................................... 1-2 2 -

Economic Feasibility Study for a 19 PAX Hybrid-Electric Commuter Aircraft

Air s.Pace ELectric Innovative Commuter Aircraft D2.1 Economic Feasibility Study for a 19 PAX Hybrid-Electric Commuter Aircraft Name Function Date Author: Maximilian Spangenberg (ASP) WP2 Co-Lead 31.03.2020 Approved by: Markus Wellensiek (ASP) WP2 Lead 31.03.2020 Approved by: Dr. Qinyin Zhang (RRD) Project Lead 31.03.2020 D2.1 Economic Feasibility Study page 1 of 81 Clean Sky 2 Grant Agreement No. 864551 © ELICA Consortium No export-controlled data Non-Confidential Air s.Pace Table of contents 1 Executive summary .........................................................................................................................3 2 References ........................................................................................................................................4 2.1 Abbreviations ...............................................................................................................................4 2.2 List of figures ................................................................................................................................5 2.3 List of tables .................................................................................................................................6 3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................8 4 ELICA market study ...................................................................................................................... 12 4.1 Turboprop and piston engine -

Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit Into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 61 | Issue 4 Article 2 1996 Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne, Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization, 61 J. Air L. & Com. 793 (1996) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol61/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. WOULD COMPETITION IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION EVER FIT INTO THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION? RUWANTISSA I.R. ABEYRATNE* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. 794 II. THE GENESIS OF AIR TRAFFIC RIGHTS ......... 795 A. TiH CHICAGO CONFERENCE ...................... 795 B. THE CHICAGO CONVENTION ..................... 800 C. POST-CHICAGO CONVENTION TRENDS ............ 802 D. THiE BERMUDA AGREEMENT ...................... 805 E. Ti ROLE OF ICAO ............................. 808 III. RECENT TRENDS .................................. 809 A. THE AI TRANSPORT COLLOQUIUM .............. 809 B. POST-COLLOQUIuM TRENDS ...................... 811 C. THE WORLD-WIDE AIR TRANSPORT CONFERENCE. 814 D. SOME INTERIM GLOBAL ISSUES ................... 816 E. OBJECTWES OF THE CONFERENCE ................ 819 F. EXAMINATION OF ISSUES -

SA227-AC Aircraft Registration: N175SW

Aircraft Data and Inspection Report Operator: Berry Aviation Date: 5.20.20 Location: Springfield Missouri Aircraft Type: Fairchild Merlin III C Serial #: AC621 Aircraft Model: SA227-AC Aircraft Registration: N175SW Date of Manufacture: Aug/1985 Current Total A/C Time: 34089.1 Current Total Airframe Cycle: 54373 Hours since Major Inspection/Overhaul: 61 Maintenance Program: FAR Part 91; Manufacturer's Recommended Inspection Type and Interval:Phase Last Inspection: Date: 10/11/2018 Operator's Representative: Title: Inspection Completed By: Laurie Stilwell Date of Completion: Inspection Type: Off-lease Work Order Reference: Notes: LH Engine Data Aircraft Registration No.: N175SW Serial #: AC621 TAT: 34089.1 Effective Date: TAC: 54373 Limits Left Hand Engine: TPE331-11U-611G Serial #: P-44414C Oprtrs Mfrs Engine H@I TSN: 24816.7 TCSN: 33347 24816 TSCAM: 5539.8 TCSCAM: 7939 7000 7000 FH ENG C@I 33346 TSO CSO Remaining ENG Time Since CAM Inspection: 5539.8 7939 1460.2 7000 7000 FH ENG Time Since Hot Section Inspection: 659.0 2841.0 3500 3500 FH ENG Time Since Gearbox Inspection: 5539.8 NA 1460.2 NA 7000 FH CYC/Time at PN SN install CSN/TSN Remaining Limit 1st Stage Turbine Wheel 3101520-4 1818244926610 0 212 19788 20000 CYC 2nd Stage Turbine Wheel 3102106-10 50134508846 761 2266 12734 15000 CYC 3rd Stage Turbine Wheel 3102655-2 10-156101-13373 0 1505 4495 6000 CYC Seal Plate 3102483-1 5-18040-2320 16713 18212 1788 20000 CYC Compressor Bearing 3103708-1 95-06049-265 5926.5 7545.2 1454.8 9000 FH 1st Stg Compressor Impeller 3108182-2 350100114 -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958-2019

Airbus A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958-2019 Contents Scope and definitions 02 1.0 2020 & beyond 05 Accidents in 2019 07 2020 & beyond 08 Forecast increase in number of aircraft 2019-2038 09 2.0 Commercial aviation accidents since the advent of the jet age 10 Evolution of the number of flights & accidents 12 Evolution of the yearly accident rate 13 Impact of technology on aviation safety 14 Technology has improved aviation safety 16 Evolution of accident rates by aircraft generation 17 3.0 Commercial aviation accidents over the last 20 years 18 Evolution of the yearly accident rate 20 Ten year moving average of accident rate 21 Accidents by flight phase 22 Distribution of accidents by accident category 24 Evolution of the main accident categories 25 Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident rates 26 Loss Of Control In-flight (LOC-I) accident rates 27 Runway Excursion (RE) accident rates 28 List of tables & graphs 29 A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958 / 2019 02 Scope and definitions This publication provides Airbus’ a flight in a commercial aircraft annual analysis of aviation accidents, is a low risk activity. with commentary on the year 2019, Since the goal of any review of aviation as well as a review of the history of accidents is to help the industry Commercial Aviation’s safety record. further enhance safety, an analysis This analysis clearly demonstrates of forecasted aviation macro-trends that our industry has achieved huge is also provided. These highlight key improvements in safety over the factors influencing the industry’s last decades. -

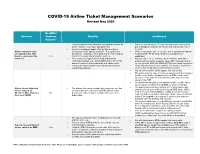

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020 Do ARC’s Scenario Systems Benefits Challenges Support? • Ticket number is easily identified, stored and retrieved by • Tracking unused tickets: To track unused tickets, agents may airline, agency, corporation and passenger. pay a third party, maintain an internal tool or manually retrieve • Agency exchanges happen often so this scenario is the data. Airline maintains value already part of the agency workflow. The agency can • Airlines may not be able to extend e-ticket expiration (being able on original ticket. (The perform the exchange in their GDS and the ticketing data to maintain the ET for longer than their standard ticket ticket is considered the Yes is fed to their mid- and back-office systems. expiration). voucher.) • ARC’s systems support this method and allow for • Agency may need to exchange ticket manually. GDS auto- refunds/exchanges (e.g., ticket validity) up to 39 months pricing tool may not be available. Note: ARC understands that based on carrier e-ticket expiration and validity rules. as of early June 2020, the GDSs/ATPCO have made updates to • Tracing the end-to-end life of the transaction is simple allow auto-pricing tools to be utilized. This ability is dependent (old and new tickets). on the airline being able to extend ticket expiration. • Not all airlines and/or GDSs support this functionality. • The airline may not have a consistent way to notify the customer that the value has been transferred to an EMD, as the travel agency’s e-mail address (instead of the passenger’s) may be stored in the PNR • The airline-issued EMD is not reported to ARC, so ARC does not recognize the airline-issued EMD for future exchanges. -

Commercial Aviation Safety Team and Joint Safety Analysis Teams

Commercial Aviation Safety Team and Joint Safety Analysis Teams Raymond E. King, Psy.D. Major, USAF, BSC Chief, Research Branch HQ Air Force Safety Center Policy, Research, and Technology Division ABSTRACT Commission and the NCARC both The number of commercial airplanes in service recommended that, to find a way to reduce will nearly double by the year 2015, going from aviation accidents, the FAA work with the airline about 12,000 airplanes today to over 23,000 in industry to establish some form of strategic 2015. On a worldwide basis, the data suggest safety plan. nearly a hull loss accident per week by the year 2015 at the current accident rate, which has In 1997, at an NCARC hearing, FAA and airline plateaued over the last decade. Many ideas for industry representatives testified about how they enhancing safety focus on technology were investigating the root causes of aviation improvements to airplanes. While such accidents. The FAA Deputy Director of Aircraft improvements are important, it should be noted Certification Service, Beth Erickson, testified for that their impact would not be significant unless the agency: "We had learned from past efforts they can be implemented on the existing airplane that safety improvements were better fleet. A large portion of the airplanes that will be accomplished when we worked with competent operating in 2007 have already been built, and aviation authorities--pilot unions, airlines, most of the rest have already been designed. The aircraft and aerospace manufacturers, and so data show there are significant factors outside of forth--all pooling our expertise to come up with the airplane design itself that influence the the best way to deal with safety issues. -

WASHINGTON AVIATION SUMMARY March 2018 EDITION

WASHINGTON AVIATION SUMMARY March 2018 EDITION CONTENTS I. REGULATORY NEWS .............................................................................................. 1 II. AIRPORTS ................................................................................................................ 3 III. SECURITY AND DATA PRIVACY ............................................................................ 6 IV. E-COMMERCE AND TECHNOLOGY ....................................................................... 7 V. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT ................................................................................ 9 VI. U.S. CONGRESS .................................................................................................... 11 VII. BILATERAL AND STATE DEPARTMENT NEWS ................................................... 13 VIII. EUROPE/AFRICA ................................................................................................... 14 IX. ASIA/PACIFIC/MIDDLE EAST ................................................................................ 17 X. AMERICAS ............................................................................................................. 19 For further information, including documents referenced, contact: Joanne W. Young Kirstein & Young PLLC 1750 K Street NW Suite 200 Washington, D.C. 20006 Telephone: (202) 331-3348 Fax: (202) 331-3933 Email: [email protected] http://www.yklaw.com The Kirstein & Young law firm specializes in representing U.S. and foreign airlines, airports, leasing companies,