Analysis of Some Copper-Alloy Items from HMAV Bounty Wrecked at Pitcairn Island in 1790

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Pitcairn's Island and American Constitutional Theory

William & Mary Law Review Volume 38 (1996-1997) Issue 2 Article 6 January 1997 Of Pitcairn's Island and American Constitutional Theory Dan T. Coenen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Dan T. Coenen, Of Pitcairn's Island and American Constitutional Theory, 38 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 649 (1997), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol38/iss2/6 Copyright c 1997 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr ESSAY OF PITCAIRN'S ISLAND AND AMERICAN CONSTITU- TIONAL THEORY DAN T. COENEN* Few tales from human experience are more compelling than that of the mutiny on the Bounty and its extraordinary after- math. On April 28, 1789, crew members of the Bounty, led by Fletcher Christian, seized the ship and its commanding officer, William Bligh.' After being set adrift with eighteen sympathiz- ers in the Bounty's launch, Bligh navigated to landfall across 3600 miles of ocean in "the greatest open-boat voyage in the his- tory of the sea."2 Christian, in the meantime, recognized that only the gallows awaited him in England and so laid plans to start a new and hidden life in the South Pacific.' After briefly returning to Tahiti, Christian set sail for the most untraceable of destinations: the uncharted and uninhabited Pitcairn's Is- * Professor, University of Georgia Law School. B.S., 1974, University of Wiscon- sin; J.D., 1978, Cornell Law School. The author thanks Philip and Madeline VanDyck for introducing him to the tale of Pitcairn's Island. -

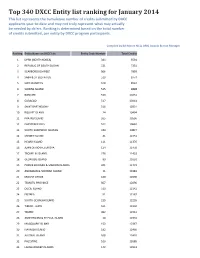

Top 340 DXCC Entity List Ranking for January 2014

Top 340 DXCC Entity list ranking for January 2014 This list represents the cumulative number of credits submitted by DXCC applicants year‐to‐date and may not truly represent what may actually be needed by dx'ers. Ranking is determined based on the total number of credits submitted, per entity by DXCC program participants. Compiled by Bill Moore NC1L ARRL Awards Branch Manager Ranking Entity Name on DXCC List Entity Code Number Total Credits 1DPRK (NORTH KOREA) 344 5591 2REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN 521 7231 3SCARBOROUGH REEF 506 7893 4SABA & ST EUSTATIUS 519 8774 5SINT MAARTEN 518 8967 6SWAINS ISLAND 515 9898 7 BONAIRE 520 10251 8 CURACAO 517 10314 9SAINT BARTHELEMY 516 10354 10 BOUVET ISLAND 24 10494 11 PRATAS ISLAND 505 10596 12 CHESTERFIELD IS. 512 10663 13 SOUTH SANDWICH ISLANDS 240 10827 14 CROZET ISLAND 41 11351 15 HEARD ISLAND 111 11376 16 JUAN DE NOVA, EUROPA 124 11450 17 TROMELIN ISLAND 276 11453 18 GLORIOSO ISLAND 99 11691 19 PRINCE EDWARD & MARION ISLANDS 201 11772 20 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLAND 11 11981 21 MOUNT ATHOS 180 12090 22 TEMOTU PROVINCE 507 12096 23 DUCIE ISLAND 513 12142 24 ERITREA 51 12167 25 SOUTH GEORGIA ISLAND 235 12220 26 TIMOR ‐ LESTE 511 12250 27 YEMEN 492 12314 28 AMSTERDAM & ST PAUL ISLAND 10 12342 29 MACQUARIE ISLAND 153 12367 30 NAVASSA ISLAND 182 12460 31 AUSTRAL ISLAND 508 12493 32 PALESTINE 510 12685 33 LAKSHADWEEP ISLANDS 142 12913 Ranking Entity Name on DXCC List Entity Code Number Total Credits 34 MARQUESAS ISLAND 509 12944 35 KINGMAN REEF 134 12990 36 ANNOBON 195 13391 37 PETER 1 ISLAND 199 13701 38 SAINT -

In Memory of the Officers and Men from Rye Who Gave Their Lives in the Great War Mcmxiv – Mcmxix (1914-1919)

IN MEMORY OF THE OFFICERS AND MEN FROM RYE WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THE GREAT WAR MCMXIV – MCMXIX (1914-1919) ADAMS, JOSEPH. Rank: Second Lieutenant. Date of Death: 23/07/1916. Age: 32. Regiment/Service: Royal Sussex Regiment. 3rd Bn. attd. 2nd Bn. Panel Reference: Pier and Face 7 C. Memorial: THIEPVAL MEMORIAL Additional Information: Son of the late Mr. J. and Mrs. K. Adams. The CWGC Additional Information implies that by then his father had died (Kate died in 1907, prior to his father becoming Mayor). Name: Joseph Adams. Death Date: 23 Jul 1916. Rank: 2/Lieutenant. Regiment: Royal Sussex Regiment. Battalion: 3rd Battalion. Type of Casualty: Killed in action. Comments: Attached to 2nd Battalion. Name: Joseph Adams. Birth Date: 21 Feb 1882. Christening Date: 7 May 1882. Christening Place: Rye, Sussex. Father: Joseph Adams. Mother: Kate 1881 Census: Name: Kate Adams. Age: 24. Birth Year: abt 1857. Spouse: Joseph Adams. Born: Rye, Sussex. Family at Market Street, and corner of Lion Street. Joseph Adams, 21 printers manager; Kate Adams, 24; Percival Bray, 3, son in law (stepson?) born Winchelsea. 1891 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 9. Birth Year: abt 1882. Father's Name: Joseph Adams. Mother's Name: Kate Adams. Where born: Rye. Joseph Adams, aged 31 born Hastings, printer and stationer at 6, High Street, Rye. Kate Adams, aged 33, born Rye (Kate Bray). Percival A. Adams, aged 9, stepson, born Winchelsea (born Percival A Bray?). Arthur Adams, aged 6, born Rye; Caroline Tillman, aged 19, servant. 1901 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 19. Birth Year: abt 1882. -

H.M.S. Bounty on April 27, 1789, She Was an Unrated, Unassuming Little

On April 27, 1789, she was an unrated, unassuming little ship halfway through a low-priority agricultural mission for the Royal Navy. A day later, she was launched into immortality as the H.M.S. Bounty site of history’s most famous mutiny. THE MISSION THE SHIP THE MUTINY Needless to say, it was never supposed to be Yes, it had sails and masts, Originally constructed For reasons having to do with the weather and this much trouble. but Bounty didn’t carry as the bulk cargo hauler the life cycle of breadfruit Royal Navy Lt. enough guns to be rated Bethia, the vessel was trees, the Bounty’s stay William Bligh was as a warship and therefore renamed and her masts in the tropical paradise commissioned to take could not officially be called and rigging completely of Tahiti stretched to the newly outfitted a “ship” — only an armed redesigned to Lt. Bligh’s five months. 24 days Bounty to the island transport. own specifications. after weighing anchor of Tahiti to pick up By any reckoning, Bounty to begin the arduous some breadfruit trees. was very small for the voyage home, Christian These were then to be mission it was asked — brandishing a bayonet carefully transported to perform and the and screaming “I am in to the West Indies, dangerous waters it hell!” — led 18 mutineers into Bligh’s cabin and where it was hoped would have to sail. Breadfruit. that their starchy, packed him off the ship. William Bligh, in melon-like fruit Bligh responded by cementing his place in naval a picture from his would make cheap history with a 4,000-mile journey, in an memoir of the mutiny. -

Captain Bligh

www.goglobetrotting.com THE MAGAZINE FOR WORLD TRAVELLERS - SPRING/SUMMER 2014 CANADIAN EDITION - No. 20 CONTENTS Iceland-Awesome Destination. 3 New Faces of Goway. 4 Taiwan: Foodie's Paradise. 5 Historic Henan. 5 Why Southeast Asia? . 6 The mutineers turning Bligh and his crew from the 'Bounty', 29th April 1789. The revolt came as a shock to Captain Bligh. Bligh and his followers were cast adrift without charts and with only meagre rations. They were given cutlasses but no guns. Yet Bligh and all but one of the men reached Timor safely on 14 June 1789. The journey took 47 days. Captain Bligh: History's Most Philippines. 6 Misunderstood Globetrotter? Australia on Sale. 7 by Christian Baines What transpired on the Bounty Captain’s Servant on the HMS contact with the Hawaiian Islands, Downunder Self Drive. 8 Those who owe everything they is just one chapter of Bligh’s story, Monmouth. The industrious where a dispute with the natives Spirit of Queensland. 9 know about Captain William Bligh one that for the most-part tells of young recruit served on several would end in the deaths of Cook Exploring Egypt. 9 to Hollywood could be forgiven for an illustrious naval career and of ships before catching the attention and four Marines. This tragedy Ecuador's Tren Crucero. 10 thinking the man was a sociopath. a leader noted for his fairness and of Captain James Cook, the first however, led to Bligh proving him- South America . 10 In many versions of the tale, the (for the era) clemency. Bligh’s tem- European to set foot on the east self one of the British Navy’s most man whose leadership drove the per however, frequently proved his coast of Australia. -

Hms Bounty and Pitcairn: Mutiny, Sovereignty & Scandal

HMS BOUNTY AND PITCAIRN: MUTINY, SOVEREIGNTY & SCANDAL LEW TOULMIN 2007 WE WILL COVER FIVE TOPICS: THE MUTINY SETTLING PITCAIRN THE DEMAGOGUE ISLAND LIFE SOVEREIGNTY & THE SEX SCANDAL THE MUTINY A MAJOR BOUNTY MOVIE APPEARS ABOUT EVERY 20 YEARS… Date Movie/Play Key Actors 1916 Mutiny on the Bounty (M) George Cross 1933 In the Wake of the Bounty (M) Errol Flynn (rumored to be descendant of mutineers John Adams & Edward Young) 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty (M) Clark Gable Charles Laughton 1956 The Women of Pitcairn Island (M) 1962 Mutiny on the Bounty (M) Marlon Brando Trevor Howard 1984 The Bounty (M) Mel Gibson Anthony Hopkins 1985 Mutiny (P) Frank Finlay …AND THERE ARE 5000 ARTICLES & BOOKS A CONSTELLATION OF STARS HAS PLAYED THESE IMMORTAL CHARACTERS THE TWO REAL MEN WERE FRIENDS AND SHIPMATES WHO CAME TO HATE EACH OTHER LIEUTENANT, LATER ADMIRAL FLETCHER CHRISTIAN WILLIAM “BREADFRUIT” BLIGH MASTER’S MATE MUTINEER ROYAL DESCENT of FLETCHER CHRISTIAN • Edward III • William Fleming • John of Gaunt • Eleanor Fleming • Joan Beaufort • Agnes Lowther • Richard Neville • William Kirby • Richard Neville • Eleanor Kirby • Margaret Neville • Bridget Senhouse • Joan Huddleston • Charles Christian • Anthony Fleming • Fletcher Christian WM. BLIGH CAN BE TRACED ONLY TO JOHN BLIGH, WHO DIED c. 1597 ALL THE FICTION IS BASED ON TRUTH TIMOR TAHITI BOUNTY PITCAIRN April 28, 1789: ‘Just before Sunrise Mr. Christian and the Master at Arms . came into my cabin while I was fast asleep, and seizing me tyed my hands with a Cord & threatened instant death if I made the least noise. I however called sufficiently loud to alarm the Officers, who found themselves equally secured by centinels at their doors . -

History of New South Wales from the Records

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

SINKING of HMS SIRIUS – 225Th ANNIVERSARY

1788 AD Magazine of the Fellowship of First Fleeters Inc. ACN 003 223 425 PATRON: Professor The Honourable Dame Marie Bashir AD CVO Volume 46, Issue 3 47th Year of Publication June/July 2015 To live on in the hearts and minds of descendants is never to die SINKING OF HMS SIRIUS – 225th ANNIVERSARY A Report from Robyn Stanford, Tour Organiser. on the Monday evening as some of the group had arrived on Saturday and others even on the Monday afternoon. Graeme Forty-five descendants of Norfolk Island First Fleeters and Henderson & Myra Stanbury, members of the team who had friends flew to Norfolk Island to celebrate the 225th anniver- helped in raising the relics from the Sirius, were the guest sary of the 19th March 1790 midday sinking of HMS Sirius. As speakers at this function and we all enjoyed a wonderful fish well as descendants of Peter Hibbs, in whose name the trip fry, salads & desserts and tea or coffee. was organised as a reunion, members of our travel group were descended from James Bryan Cullen, Matthew Everingham, A special request had been to have a tour with the historian, Anne Forbes, James Morrisby, Edward Risby & James Wil- Arthur Evans who has a massive knowledge about the is- lams. land. Taking in the waterfront of Kingston, Point Hunter, where he pointed out examples of volcanic rock & the solitary The Progres- Lone Pine noted by Captain Cook on his second voyage Arthur sive Dinner on also gave a comprehensive talk on the workings of the Lime the night of Kilns, and the Salt House with its nearby rock-hewn water tub. -

In the Privy Council on Appeal from the Court of Appeal of Pitcairn Islands

IN THE PRIVY COUNCIL ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF PITCAIRN ISLANDS No. of 2004 BETWEEN STEVENS RAYMOND CHRISTIAN First Appellant LEN CALVIN DAVIS BROWN Second Appellant LEN CARLISLE BROWN Third Appellant DENNIS RAY CHRISTIAN Fourth Appellant CARLISLE TERRY YOUNG Fifth Appellant RANDALL KAY CHRISTIAN Sixth Appellant A N D THE QUEEN Respondent CASE FOR STEVENS RAYMOND CHRISTIAN AND LEN CARLISLE BROWN PETITIONERS' SOLICITORS: Alan Taylor & Co Solicitors - Privy Council Agents Mynott House, 14 Bowling Green Lane Clerkenwell, LONDON EC1R 0BD ATTENTION: Mr D J Moloney FACSIMILE NO: 020 7251 6222 TELEPHONE NO: 020 7251 3222 6 PART I - INTRODUCTION CHARGES The Appellants have been convicted in the Pitcairn Islands Supreme Court of the following: (a) Stevens Raymond Christian Charges (i) Rape contrary to s7 of the Judicature Ordinance 1961 and s1 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 (x4); (ii) Rape contrary to s14 of the Judicature Ordinance 1970 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956. Sentence 4 years imprisonment (b) Len Carlisle Brown Charges Rape contrary to s7 of the Judicature Ordinance 1961, the Judicature Ordinance 1970, and s1 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 (x2). Sentence 2 years imprisonment with leave to apply for home detention The sentences have been suspended and the Appellants remain on bail pending the determination of this appeal. HUMAN RIGHTS In relation to human rights issues, contrary to an earlier apparent concession by the Public Prosecutor that the Human Rights Act 1978 applied to the Pitcairn Islands, it would appear not to have been extended to them, at least in so far as the necessary protocols to the Convention have not been signed to enable Pitcairners to appear before the European Court: R (Quark Fisheries Ltd) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2005] 3 WLR 7 837 (Tab ). -

Mutiny on the Bounty: a Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia

4 Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty: A Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia Introduction Various Bounty narratives emerged as early as 1790. Today, prominent among them are one 20th-century novel and three Hollywood movies. The novel,Mutiny on the Bounty (1932), was written by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, two American writers who had ‘crossed the beach’1 and settled in Tahiti. Mutiny on the Bounty2 is the first volume of their Bounty Trilogy (1936) – which also includes Men against the Sea (1934), the narrative of Bligh’s open-boat voyage, and Pitcairn’s Island (1934), the tale of the mutineers’ final Pacific settlement. The novel was first serialised in the Saturday Evening Post before going on to sell 25 million copies3 and being translated into 35 languages. It was so successful that it inspired the scripts of three Hollywood hits; Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny strongly contributed to substantiating the enduring 1 Greg Dening, ‘Writing, Rewriting the Beach: An Essay’, in Alun Munslow & Robert A Rosenstone (eds), Experiments in Rethinking History, New York & London, Routledge, 2004, p 54. 2 Henceforth referred to in this chapter as Mutiny. 3 The number of copies sold during the Depression suggests something about the appeal of the story. My thanks to Nancy St Clair for allowing me to publish this personal observation. 125 THE BOUNTY FROM THE BEACH myth that Bligh was a tyrant and Christian a romantic soul – a myth that the movies either corroborated (1935), qualified -

HMS Bounty Replica Rests in Peace Hampton Dunn

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Publications 1-1-1960 HMS Bounty replica rests in peace Hampton Dunn Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/flstud_pub Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Community-based Research Commons Scholar Commons Citation Dunn, Hampton, "HMS Bounty replica rests in peace" (1960). Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Publications. Paper 2700. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/flstud_pub/2700 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HMS BOUNTY REPLICA RESTS IN PEACE ST. PETERSBURG --- The original HMS Bounty had a stormy and infamous career. But a replica of the historic vessel rests peacefully amid a Tahitian setting at the Vinoy Park Basin here and basks in the compliments tourists pay her. Bounty II was reconstructed from original drawings in the files of the British Admiralty by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer movie studio. After starring in the epic "Mutiny on the Bounty" the ship was brought here for permanent exhibit a 60,000 mile journey to the South Seas for the filming and promotional cruises. The original Bounty was a coastal trader named Bethia. The Navy of King George III selected her for Lt. William Bligh's mission to the South Seas in 1789. Her mission: To collect young transplants of the breadfruit tree and carry them to Jamaica for cultivation as a cheap food for slaves. -

1872: Survivors of the Texas Revolution

(from the 1872 Texas Almanac) SURVIVORS OF THE TEXAS REVOLUTION. The following brief sketches of some of the present survivors of the Texas revolution have been received from time to time during the past year. We shall be glad to have the list extended from year to year, so that, by reference to our Almanac, our readers may know who among those sketches, it will be seen, give many interesting incidents of the war of the revolution. We give the sketches, as far as possible, in the language of the writers themselves. By reference to our Almanac of last year, (1871) it will be seen that we then published a list of 101 names of revolutionary veterans who received the pension provided for by the law of the previous session of our Legislature. What has now become of the Pension law? MR. J. H. SHEPPERD’S ACCOUNT OF SOME OF THE SURVIVORS OF THE TEXAS REVOLUTION. Editors Texas Almanac: Gentlemen—Having seen, in a late number of the News, that you wish to procure the names of the “veteran soldiers of the war that separated Texas from Mexico,” and were granted “pensions” by the last Legislature, for publication in your next year’s Almanac, I herewith take the liberty of sending you a few of those, with whom I am most intimately acquainted, and now living in Walker and adjoining counties. I would remark, however, at the outset, that I can give you but little information as to the companies, regiments, &c., in which these old soldiers served, or as to the dates, &c., of their discharges.