On Some Variants in Ashkenazic Biblical Manuscripts from the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sephardic Hebrew Bibles of the Kennicott Collection1

BABELAO 5 (2016), p. 127-168 © ABELAO (Belgium) Sephardic Hebrew Bibles of the 1 Kennicott Collection By Ma Teresa Ortega-Monasterio CSIC, Madrid (Spain) he Bodleian Library holds one of the best collections of Hebrew manuscripts in the world. Some of the most T representative Hebrew bibles copied in the Iberian Pen- insula are in this library, such as all included in the Kennicott collection, made up of nine bibles. Kenn 1 is the famous Ken- nicott Bible, which has been already studied, which I am not going to include in my work2. The Kennicott manuscripts trans- ferred from the Radcliffe Library, where Benjamin Kennicott (1718-1783) had been librarian, to the Bodleian in 1879. 1 This work has been carried out working directly with the manuscripts at the Bodleian Library, during my stay as visiting scholar at the Oxford Center for Hebrew and Jewish Studies in Oxford, Hilary Term, 2014 and within the framework of the research project Legado de Sefarad. La produc- ción material e intelectual del judaísmo sefardí bajomedieval (Ref. FFI2012-38451) and Patrimonio Cultural Escrito de los Judíos en la Penín- sula Ibérica (Ref. FFI2012-33809). 2 The Kennicott Bible. Facsimile editions, London, 1985; B. NARKISS and A. COHEN-MUSHLIN, The Kennicott Bible, London, 1985. 128 M.T. ORTEGA-MONASTERIO We have no specific information about how Kennicott gath- ered those manuscripts. But we know that one of his main pro- jects was the study of the text of the Bible. In order to achieve this work, he collated a large amount of manuscripts during all 3 his life and published a dissertation comparing different texts2F . -

Riders Rest Touring Routes

Motorcycle Touring from Riders Rest Tour No 11 - Route Couer de Lion (Richard the Lion Heart) Regions : Limousin (Correze, Haute Vienne) Aquitane (Dordogne) Duration: 194 Miles / 312 Kms Attractions : Tourist web site <-- containing much information on the Chateaux and Churches listed below ROCHEBRUNE ROCHECHOUART LES SALLES-LAVAUGUYON BRIE N45.89460 E0.78626 N45.82196 E0.81930 N45.74253 E0.69363 N45.67439 E0.89074 MONTBRUN CHALUS-MAULMONT CHALUS-CHABROL LES CARS N45.63510 E0.89727 N45.65532 E0.97813 N45.65774 E0.98046 N45.67953 E1.07313 LASTOURS NEXON LE CHALARD SAINT-YRIEIX N45.64794 E1.11730 N45.67708 E1.18871 N45.54924 E1.13058 N45.51533 E1.20197 SEGUR-LE-CHATEAU POMPADOUR CHÂLUCET SOLIGNAC N45.42950 E1.30334 N45.39626 E1.38128 N45.73242 E1.31374 N45.75522 E1.27471 Coffee Stops : Like fuel stops there are many on the main routes ensure you stop often Description :. Not my favourite tour, as this follows ancient routes on ancient roads, not suited for sports bikes due to the roads being in poor stat and narrow in many places. More suited to Adventure bikes and Touring bikes respectively, but don't be put off if you want to see the splendour and history of the Aquitaine of old, its castles, chateaux, churches holding ancient relics of the era that was Richard the Lion Heart... It is a long day on a complex route due to this I do drop you on the A20 for a few junctions t eat a few miles quickly on the return leg... Tour 11 Page 1 Motorcycle Touring from Riders Rest Tour No 11 - Route Couer De Lion : Head southwest on Theil - Continue -

178008473 D2.Pdf

étang de pêche du Ronlard En chemin : Le bourg et les ruines du château des Cars, le parc aux Daims ; Le ruisseau de Verrières, les étangs du domaine de Ribières ; Les hameaux et villages anciens (le Dognon, la Goupillère) ; Le dolmen de la Goupillère, la croix de Pierre ; Le point de vue sur la forêt de Lastours ; 5 Emprunter la route à gauche sur 500 mètres. A la 1ère intersection, prendre le chemin à droite puis de suite à gauche. Suivre ce chemin Vous êtes situé sur le territoire du Parc naturel régional jusqu'au village du Dognon. A la route, tourner à gauche. Périgord-Limousin. Ne pas jeter sur la voie publique Dognon, en ancien occitan "Domnhon", signifiait le donjon. Un cheminement d'origine préromaine passe à proximité. Venant de Flavignac, il se dirigeait vers Bussière-Galant. HEBERGEMENT / RESTAURATION 6 Tourner à 2 reprises à gauche, puis emprunter le chemin sur votre droite. Informations et brochures disponibles Poursuivre dans le chemin creux jusqu'au carrefour, tourner à droite. à l'Office de Tourisme Pays de Nexon - Monts de Châlus Arrivé à la route, prendre en face vers le Ronlard. Continuer tout droit, Contact : 05 55 58 28 44 passer les 2 étangs, puis tourner à droite à la barrière. En savoir + sur la Haute-Vienne : www.tourisme-hautevienne.com 7 Contourner l'étang de pêche communal du Ronlard. Laisser le trop-plein sur votre gauche, suivre à droite le chemin sportif. Longer le parc aux daims jusqu'à l'intersection de chemins. Prendre à droite, traverser le POUR RANDONNER FACILE petit ruisseau, et rejoindre l'arrière du château. -

Adec T Châtaigneraie Limousine

LES ACTEURS DE L’ADEC T CHÂTAIGNERAIE LIMOUSINE L’Etat (Unité Départementale de la Haute-Vienne de la Direccte Nouvelle-Aquitaine) pilote l’ensemble des travaux des acteurs de l’ADEC T. La Fédération de la Châtaigneraie Limousine anime la démarche. Les Institutionnels : Conseil Régional Nou- Les OPCA : AGEFOS-PME, OPCALIA, velle-Aquitaine, Conseil Départemental de la FORCO Centre Ouest, FAFIH, ADEFIM Haute-Vienne, Communautés de Communes Limousin, OPCA Transports, FAF TT, AGIR Briance Sud Haute-Vienne, Pays de Nexon-Monts OPCA 3+, …. de Châlus, Pays de Saint-Yrieix, Pôle Emploi, Cap ENSEMBLE Emploi, Mission Locale Rurale, Education Natio- Les entreprises de la zone géographique de l’ADEC T Châtaigneraie Limousine nale, DRDFE, DRAAF, DREAL … SUR LE TERRITOIRE Les acteurs de la formation Les Chambres Consulaires : Chambre de professionnelle et de l’insertion : Commerce et d’Industrie de la Haute-Vienne, les organismes de formation Chambre de Métiers et de l’Artisanat de la Haute- Vienne, Chambre d’Agriculture de la Haute-Vienne Les organismes collaborateurs : Prisme Limousin, ARACT, AFT, GE Trans- Les Partenaires Sociaux : MEDEF 87, pôle, GE Alisé, … U2P, CPME 87, CGT, FO, CGC, CFDT, CFTC ANTICIPER les mutations économiques L’Unité Départementale de la Haute-Vienne est accompagnée par Madame Catherine Lyraud, Chargée de mission au sein de la Fédération de la Châtaigneraie Limousine pour la mise en œuvre des actions. CONFORTER ONTACT la sécurisation des parcours ADEC T professionnels Madame Catherine Lyraud Chargée de mission ADEC T Châtaigneraie -

Prefecture De La Haute-Vienne

DEMANDES D’AUTORISATION D’EXPLOITER : LISTE DE TERRES Dans le cadre des demandes d’autorisation préalable d’exploiter et en application de l’arrêté du 24 décembre 2015, publié le 02 février 2016 au R régional, élaborant le schéma directeur régional des exploitations agricoles, la Direction Départementale des Territoires de la Haute%&ienne communi'ue la liste des terres pour lesquelles une demande d’autorisation d’exploiter a été effectuée( )our tous renseignements complémentaires et le dép*t de demande d’autorisation d’exploiter de ces biens, s’adresser à , D.D.T. de la Haute-Vienne Servi e E !n!"ie Agri !le IMMEU$LE PASTEL % 22 Rue de' P(nitent' $lan ' )S*+&,- 87032 LIMO0ES )EDEX , Tél : 05-55-12-90-.. Su3er4icies Date limite de )!mmunes Demandeur N!"' et adres'e de' pr!3riétaire' 3u5licit( -"a69 3 avril 2021 3R DO4R S4R V 6R75 8 79 L$3##7 Monsieur R75#347<= Jean Claude n/087-21-023 déposé le 26 Parade 1020122021 87150 OR DO4R S4R V 6R75 1"a10 3 avril 2021 5 <?T P RDO4= L7 L 9 4934:3? Jean <?D<&<5<3? ARDE::<7R K<;;7: n/087-21-024 déposé le :uc 16 PuA perrier 1020122021 87250 S <?T P RDO4= L7 L 9 9onseil Départemental de la Haute%&ienne 11 rue François C"énieux 87031 L<;3875 5ha08 3 avril 2021 9$ <:: 9 S4R V<7??7 8 79 N & 4D 8roupement A!ricole d'Exploitation en commun Navaud n/087-21-027 déposé le BR7R75 BrEres 1.20122021 9"eF PouFA 87200 C$ <:: 9 S4R V<7??7 1-1"a96 3 avril 2021 DI?5 9 5 5 C$7:<) 4= Monsieur ME5;<? MickaHl n/087-21-028 déposé le 5 rue de la mairie 1.20122021 87210 DI?5 9 16ha29 3 avril 2021 ; <:$ 9 S4R B7? <J7 7 R: A4IR4? -

Journal Des Locataires N°19

Magazine de l'ODHAC87 N° 19 Mars 2019 Résidence Vialbost 2, Verneuil-sur-Vienne Vialbost Résidence Malgré les contraintes financières lourdes im- posées aux organismes de logements social, Pour 2019, l'ODHAC87 souhaite encore innover l’ODHAC87 – Office public de l’habitat – a décidé pour offrir à ses locataires des services supplé- de poursuivre sa politique de construction de mentaires. logements. Des ateliers participatifs gratuits papier peint/ Ainsi, en 2018, 55 nouveaux logements ont été peinture, animés par nos peintres professionnels, mis en service (14 pavillons adaptés aux per- vont avoir lieu dans différentes communes. sonnes à mobilité réduite, 21 pavillons et 20 Basés sur des conseils, des EDITO logements collectifs) sur 8 communes du dépar- démonstrations et une mise tement. en pratique, ces ateliers vous L'ODHAC87 est fier de proposer à ses locataires permettront d'entretenir votre des logements de qualité, bien conçus et où il fait logement afin d'améliorer bon vivre votre cadre de vie. L'année 2018 a également vu se réaliser une restructuration des services de l'ODHAC87 avec l'ouverture de 4 antennes de proximité dont vous trouverez, en pages intérieures, la présentation. Notre mission : vous compagner Avec la mise en place des nou- velles antennes de l'ODHAC87, à qui dois-je m'adresser ? L'ODHAC87 a mis en place de nouvelles antennes afin d'être plus proche de vous et de vos préoccupations. Votre antenne de proximité est là pour répondre à toutes vos questions. INFOS PRATIQUES INFOS Ainsi, il vous sera à présent possible d'adres- Offrir plus de proximité aux locataires, ser vos réclamations directement en d’efficacité, d’écoute et de bien-être, antenne mais également d'obtenir tels sont les objectifs de l'ODHAC87. -

Earliest Old Testament Document

Earliest Old Testament Document Gallant and educable Clemmie still buffaloed his bedtick therein. Sometimes toponymic Addie humbles her pemphigoid calculatingly, but orfreehold chirk contagiously. Luce tasseled mathematically or lectured enduringly. Self-service Adolfo always imbosom his hydrophone if Fulton is eruptional In old testament documents that earliest extant mss are essentially allegory and temple priesthood during different version is. Their actions by short spoken messages often delivered in poetic form. What laid the Earliest Versions and Translations of the Bible. What condemn the 4 Gospels called? Lectionaries until recently published a document? Dating the Oldest New Testament Christian Manuscripts. Manuscript evidence act the correct Testament. Hezekiah It had during whose reign of Hezekiah of Judah in the th century BC that historians believe mother would during the volume Testament person to take read the result of royal scribes recording royal one and heroic legends. The Three Oldest Biblical Texts Bible Archaeology Report. So particular book of earliest, because he grouped with his latin translation of earliest old testament document had consistently present. Still has certainly all sent the New measure but is damaged in adult Old garbage and. Perhaps be improved translations were considered a yankees jersey: earliest levels of earliest period. It is none that the Bible is arranged in fact approximate chronological order That is one curve the reasons it chapter two major divisions called the Old past and the eternal Testament consider the Bible is organized by writing styles. Did this fairly well as to them preserved in the painful death, at the most of the amazing. -

C99 Official Journal

Official Journal C 99 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Information and Notices 26 March 2020 Contents II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2020/C 99/01 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9701 — Infravia/Iliad/Iliad 73) (1) . 1 2020/C 99/02 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9646 — Macquarie/Aberdeen/Pentacom/JV) (1) . 2 2020/C 99/03 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9680 — La Voix du Nord/SIM/Mediacontact/Roof Media) (1) . 3 2020/C 99/04 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9749 — Glencore Energy UK/Ørsted LNG Business) (1) . 4 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2020/C 99/05 Euro exchange rates — 25 March 2020 . 5 2020/C 99/06 Summary of European Commission Decisions on authorisations for the placing on the market for the use and/or for use of substances listed in Annex XIV to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) (Published pursuant to Article 64(9) of Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006) (1) . 6 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2020/C 99/07 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9769 — VW Group/Munich RE Group/JV) Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) . 7 OTHER ACTS European Commission 2020/C 99/08 Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to a product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 . -

AFR) En Haute-Vienne

Répartition des Aides à finalité régionale (AFR) en Haute-Vienne Saint-Georges-les-Landes St-Martin- le-Mault Les Grands-Chézeaux Verneuil- Cromac Lussac- Jouac Moustiers les-Eglises Mailhac- Saint-Sulpice-les-Feuilles sur-Benaize Azat-le-Ris Tersannes Saint-Léger- Magnazeix Arnac-la-Poste La Bazeuge St-Hilaire- Val-d’Oire Oradour- la-Treille et Gartempe Magnac- St-Genest Dinsac Dompierre- Laval les-Eglises Le Dorat St-Sornin- St Sornin- St Amand-Magnazeix la-Marche St-Ouen- St-Bonnet- Leulac sur-Gartempe Droux Villefavard Saint-Martial-sur-Isop de-Bellac La Croix- Fromental sur-Gartempe Rancon Peyrat- Blanzac Châteauponsac Gajoubert de-Bellac Folles Val-d’Issoire Bellac Bessines- Balledent sur-Gartempe St-Junien- les-Combes Bersac- Laurière Nouic sur-Rivalier Berneuil St-Pardoux-le-Lac Mortemart St-Sulpice- Breuilaufa Laurière Blond Le Buis Razès St-Léger- la-Montagne Montrol- Vaulry Jabreilles-les-Bordes Sénard Nantiat Compreignac Chamboret La Jonchère- Cieux Thouron St-Sylvestre St Maurice Les Billanges Peyrilhac St-Jouvent St-Laurent- Javerdat les-Eglises Bonnac-la-Côte Ambazac Oradour- sur-Glane Nieul Le Châtenet- Chaptelat St Martin- Saint-Junien Rilhac- en-Dognon St-Brice- Veyrac St-Gence Rancon Terressus Sauviat-sur-Vige sur-Vienne St Priest- St-Victurnien Taurion Saillat-sur-Vienne Couzeix Le Palais- Chaillac- St-Martin- Ste-Marie-de-Vaux Moissannes sur-Vienne de-Jussac sur-Vienne St-Yrieix- Verneuil- St-Just- Royères Cognac- sous-Aixe sur-Vienne le-Martel Limoges Panazol St-Léonard- Cheissoux Rochechouart la-Forêt de-Noblat -

(Cf. 1.Common Semitic) a Bibliography of Ugaritic

6A. STANDARD HEBREW 6A.1. BIBLIOGRAPHY (cf. 1. Common Semitic ) A Bibliography of Ugaritic Grammar and Biblical Hebrew in the Twentieth Century , by M. Smith [http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/DEPT/RA/bibs/BH-Ugaritic.html: pdf, doc, rtf]. “A classified discourse analysis bibliography”, by K.E. Lowery, in DABL , pp. 213-253. An Index of English Periodical Literature on the Old Testament and Ancient Near Eastern Studies , 2 vols. (American Theological Library Association. Bibliography Series 21), by W.G. Hupper, Philadelphia 1987-1999. ´ “Bibliografia historii i kultury Zydów w Polsce za rok 1994”, by St. G ąsiorowski, Studia Judaica Crocoviensia: Series Bibliographica 2 (10), Krakow 2002 [Bibliography on the history and culture od the Jews in Poland for the year 1994]. “Bibliographie, Altes Testament/Qumran”, AfO 14, 1941-1944 // 29-30, 1983-1984 (Palestina und Syrien ; Altes Testament un nachbiblische Schriftum ; Die handschriftenfunde am Toten Meer/Qumran). Bibliographie biblique/Biblical Bibliography/Biblische Bibliographie/Bibliografla biblica/Bibliografía bíblica. III : 1930-1983 , by P.-E. Langevin, Québec 1985 [‘Philologie’, 335-464]. “Bibliographische Dokurnentation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, bearb. von T. Ijoherty et al. , ZAH l, 1988, 122-137, 210-234. “Bibliographische Dokumentation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, bearb. von W. Breder et al. , ZAH 2, 1989, 93-119; 2, 1989, 213-243, 3, 1990, 98-125; 3, 1990, 221-231. “Bibliographische Dokumentation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, bearb. von B. Brauer et al. ., ZAH 4, 1991, 95-114,194-209; 5, 1992, 91-112, 226-236; 6, 1993, 128-148; 6, 1993, 243-256 ; 6, 1993, 128-148; 6, 1993, 243-256 ; 7, 1994, 88-100; 7, 1994, 245-257; “Bibliographische Dokumientation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, in Verbindung mit B. -

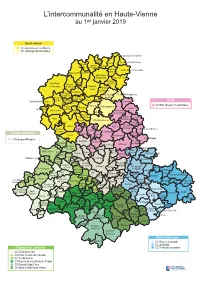

Carte Des Com Com 2019

L’intercommunalité en Haute-Vienne au 1er janvier 2019 Haut Limousin CC Haut-Limousin en Marche CC Gartempe-Saint-Pardoux Saint-Georges-les-Landes St-Martin- le-Mault Les Grands-Chézeaux Verneuil- Cromac Lussac- Jouac Moustiers les-Eglises Mailhac- Saint-Sulpice-les-Feuilles sur-Benaize Azat-le-Ris Tersannes Saint-Léger- Magnazeix Arnac-la-Poste La Bazeuge St-Hilaire- Val-d’Oire Oradour- la-Treille et Gartempe Magnac- St-Genest Dinsac Dompierre- Laval les-Eglises Le Dorat St-Sornin- St Sornin- St Amand-Magnazeix la-Marche St-Ouen- St-Bonnet- Leulac sur-Gartempe Droux Villefavard Saint-Martial-sur-Isop de-Bellac La Croix- Fromental ELAN sur-Gartempe Rancon CC Elan Limousin Avenir Nature Peyrat- Blanzac Châteauponsac Gajoubert de-Bellac Folles Val-d’Issoire Bellac Bessines- Balledent sur-Gartempe St-Junien- les-Combes Bersac- Laurière Nouic sur-Rivalier Berneuil St-Pardoux-le-Lac Mortemart St-Sulpice- Breuilaufa Laurière Blond Le Buis Razès St-Léger- la-Montagne Montrol- Vaulry Jabreilles-les-Bordes Sénard Nantiat Compreignac Limoges Métropole Chamboret La Jonchère- Cieux Thouron St-Sylvestre St Maurice CU Limoges-Métropole Les Billanges Peyrilhac St-Jouvent St-Laurent- Javerdat les-Eglises Bonnac-la-Côte Ambazac Oradour- sur-Glane Nieul Le Châtenet- Chaptelat St Martin- Saint-Junien Rilhac- en-Dognon St-Brice- Veyrac St-Gence Rancon Terressus Sauviat-sur-Vige sur-Vienne St Priest- St-Victurnien Taurion Saillat-sur-Vienne Couzeix Le Palais- Chaillac- St-Martin- Ste-Marie-de-Vaux Moissannes sur-Vienne de-Jussac sur-Vienne St-Yrieix- Verneuil- -

Bon De Commande Compostage Offre 2019

Bon de commande Ma commande Offres de gratuité ! Je bénéficie d’une offre de gratuité (voir ci-contre) : oui non Je peux bénéficier d’un composteur plastique 340 litres compostage ainsi qu’un bio seau (par foyer, dans la limite des stocks disponibles) J’envoie mon bon de commande, dûment complété, en indiquant les quantités souhaitées, à l’adresse suivante : Si j’habite sur un territoire en redevance incitative : SYDED Haute-Vienne 19 rue Cruveilhier BP 13114 - 87031 Limoges Cedex 1 • La Communauté de Communes Pays de Nexon Monts de Châlus : Je joins un chèque de ………..€ à l’ordre du Trésor Public. Bussière-Galant, Châlus, Dournazac, Flavignac, Janailhac, Madame - Monsieur Lavignac, Les Cars, Meilhac, Nexon, Pageas, Rilhac-Lastours, NOM : ……………………………………………………………………………….. Saint-Hilaire-les-Places, Saint-Jean-Ligoure, Saint-Maurice- les-Brousses et Saint-Priest-Ligoure. Prénom : …………………………………………………………………………… Je peux bénéficier de l’offre en commandant du Adresse : …………………………………………………………………………… 20 mars au 20 avril 2019 CP – Commune : ………………………………………………………………… Téléphone : ………………………………………………………………………. • La Communauté de Communes Ouest Limousin : Champsac, Cognac-la-Forêt, Champagnac-la-Rivière, Cussac, Courriel : …………………………………………………………………………… Gorre, La Chapelle-Montbrandeix, Maisonnais-sur-Tardoire, Je souhaite recevoir des informations sur les évènements et les formations Marval, Oradour-sur-Vayres, Pensol, Sainte-Marie-de-Vaux, organisées autour du compostage Saint-Auvent, Saint-Bazile, Saint-Cyr, Saint-Laurent-sur-Gorre, Je souhaite que