ALEX ZUKAS Explaining Unemployed Protest in the Ruhr at the End of the Weimar Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

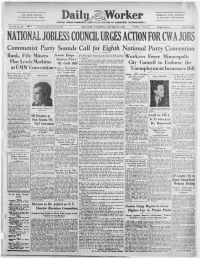

Communist Party Sounds Call for Eighth National Party Convention Senate Keeps Eighth National Convention of the C.P.UJS.A

ASK YOUR FRIENDS AMERICA’S ONLY WORKING To Subscribe for the “Daily'" DailqliVVorker CLASS DAILY NEW'SPAPER CENTRAL ORGAN COMMUNIST PARTY U.S.A. (SECTION OF COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL) 26 as matter at tho Post at Vol. Entered second-class Offlct WEATHER: Probably XI, No. 24 New York, N. Y, under th« Act of March 8. 1879 NEW YORK, SATURDAY, JANUARY 27, 1934 rain. (Eight Pages) Price 3 Cents NATIONAL JOBLESS COUNCIL URGES ACTION FOR CWA JOBS Communist Party Sounds Call for Eighth National Party Convention Senate Keeps Eighth National Convention of the C.P.UJS.A. is called to meet in Rank, File Miners rECleveland, Ohio, on April 3, 1934, and continue until Its deliberations are concluded. Workers Force Minneapolis Secrecy Part Since the Seventh Convention, profound charges have taken place in the world, and in the United States. There have been also far- Flay Lewis Machine reaching changes in the life and growth of the revolutionary movement Gold among workers. to Os Bill the American City Council Endorse the Our Seventh Convention In 1930 confirmed the Party’s final rejection Defeats Amendments; of the opportunist line of the Loves tone group, whose swift degeneration atUMW Convention into the blackest forms of renegacy kept time with the swiftly deepening Bill “40 Wage capitalism. struggle Leninist against Insurance Per Cent crisis of By relentless for the line, Unemployment Cut,” Senator Says the right opportuniss and Trotskyist counter-revolutionaries, our Party Resolutions Indicate defeated and isolated these enemies of the working class. It placed the By Party squarely on the road to the building of a mass Communist Party, Jobless, CWA Workers Committees of Action Wide Opposition to the Bill Gebert MARGUERITE YOUNG (Daily Worker Washington Bureau) which is organizing and leading the growing upsurge of the American Jam City Council Harry Hopkins on All CWA Projects workers against the catastrophic conditions of the crisis. -

Popular Radicalism in the 1930S: the Ih Story of the Workers' Unemployment Insurance Bill Chris Wright [email protected]

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 4 2018 Popular Radicalism in the 1930s: The iH story of the Workers' Unemployment Insurance Bill Chris Wright [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.6.1.007547 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2018) "Popular Radicalism in the 1930s: The iH story of the Workers' Unemployment Insurance Bill," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.6.1.007547 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol6/iss1/4 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Radicalism in the 1930s: The iH story of the Workers' Unemployment Insurance Bill Abstract Historiography on the Great Depression in the U.S. evinces a lacuna. Despite all the scholarship on political radicalism in this period, one of the most remarkable manifestations of such radicalism has tended to be ignored: namely, the mass popular movement behind the Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill. This bill, which the Communist Party wrote in 1930, was introduced in Congress three times, in 1934, ’35, and ’36, as an alternative to the far more conservative Social Security Act. Its socialistic nature ensured that it never had any chance of becoming law, but it also enabled it to become enormously popular among Americans across the country, who were more enthusiastic about radical social democracy than has often been appreciated. -

FDR's New Deal and the Fight for Jobs

FDR's New Deal and the fight for jobs isreview.org/issue/70/fdrs-new-deal-and-fight-jobs Review by Annie Levin Put to Work: The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depressoin By Nancy E. Rose Monthly Review Press, 2009 (2nd edition) · 160 pages · $15.00 When Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in March 1933, 12 million people were unemployed, out of a total U.S. workforce of approximately 50 million. Investment in new plant and machinery had come to a virtual standstill. Estimates of the numbers of homeless transients ranged from half a million to 5 million. There were protests, riots, and strikes across the country, but the previous Hoover administration had done virtually nothing to address the question of jobs or relief. In this short but excellent survey, Put To Work: The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depression, Nancy Rose argues that FDR began the first jobs programs of the New Deal because he, unlike his predecessor, understood the threat that working class rebellion posed to restoring capitalism’s stability. Rose writes: Although much of the business community steadfastly opposed federal unemployment relief, increasing destitution, continuing protests, the exhaustion of traditional sources of relief, and pleas from local and state governments compelled the Roosevelt administration to act. The alternative, as historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., wrote in his study of this period, might be revolution. In just 103 pages, Rose deftly sketches the history of the New Deal jobs programs. We get a sense of their grand scale—particularly compared to anything being discussed by the Obama administration in response to today’s crisis—but also their profound concessions to racism, sexism, and the business-as-usual status quo. -

Misery of Unemployed Grows in All Industrial Centers

DAILY WORKER, NEW Yoiviv, iuiibJAV, i'EKKUAKY 17, 19.11 Page three MISERY OF UNEMPLOYED GROWS IN ALL INDUSTRIAL CENTERS Murphy Cuts Down on Even Joe Judson and Morris Nemser Needle Workers KAZAKSTAN SOVIET MASS MEET Charity As Many Workers Renounce Lovestoneism On Picket Line PROTESTS LYNCHINGS IN U. S. Need Immediate Reliet While the renegade Lovestone diametrically opposed, and have stone group as an active member. I to Fight Speedup Big* Meeting of Kazakstan Workers Greets group as a whole Is seeking new av- nothing in common with Party in- helped to raise funds for the Revo- j League of Struggle for Negro Rights Family enues and new' allies, even more open terests. The very elementary and lutionary Age, which was and is Dressmakers Strike Negro Worker Tells How His Went enemies of the working class, for their basic principle upon which is based slandering and attacking the Party NEW YORK.—At a meeting of the The letter, coming in time for counter-revolutionary activities, indi- Communist organization and without in an open coimter-revolutionary Today Against Soli- Hungry, Waiting for Some Relief Starv- district committee of MOPR (Rus- darity Week organized by the Inter- vidual members of the group, espe- which it ceases to function as a Com- way. I wsa a leading agent in the ! sian International Labor Defense) in ; Defense cially munist organization completely Section of ation Wages national Labor in commemo- those who are closer to the was so-called Four the Love- Kazakstan, of the Middle Asian ration of Frederick Douglass's Out February 25th to Force Cash Relief proletarian masses, are begining to forgotten by me; one of the basic stone group in the struggle against one I birth- All On rnoueAi.KQVK) Soviet Republics, a. -

Unemployment Management: First Step in Non-Labor Management

International Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences Volume 1, Issue 2, ISSN (Online): 2349–5219 Unemployment Management: First Step in Non-labor Management Dr. Achyut Aryal Abstract – This research article is an introduction about a anathema to the American spirit of work and self- new approach on management, its background, nature, sufficiency. Therefore, it should be dispensed to as few as process, elements and models which introduce a new kind of possible and made as harsh as possible to discourage management philosophy for academic and social discourse. reliance upon it. Accordingly, very little was given, and Furthermore it asks for further depth research in the field then only to a handful of the aged and crippled, widowed with experimentation. It constructs the claim unemployment is not a problem and hazard of the society but it is an unique and orphaned to “deserving” people who clearly were not opportunity to know, learn, understand human society from able to work[3]. historical, theoretical and economic as well as many other These practices were not only a reflection of harshly perspectives which are in existence. It has such a nature to individualistic American attitudes. They were also a link all societal phenomena together. Moreover reflection of American economic realities. Work and self- unemployment management is first step in broad non-labor reliance meant grueling toil at low wages for many people. management sector. From which we can study half of the So long as that was so, the dole could not be dispensed existence, which is still in dark. permissively for fear some would choose it over work. -

“Starve and Be Damned!”: Communists and Canada's Urban Unemployed

Manley, John “Starve and be damned!”: Communists and Canada’s urban unemployed Manley, John (2008) “Starve and be damned!”: Communists and Canada’s urban unemployed, in: Labouring Canada: class, gender and race in Canadian working-class history pp.210-223 Publisher: Oxford University Press, Oxford ISSN/ISBN 97801985425338 External Assessors for the University of Central Lancashire are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: o access and download a copy o print out a copy Please note that this material is for use ONLY by External assessors and UCLan staff associated with the REF. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with the REF. You may retain such copies after the end of the REF, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by the University of Central Lancashire. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e- mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. -

A Popular Constitutional History of the Angelo Herndon Case

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 1992 Rouge et Noir Reread: A Popular Constitutional History of the Angelo Herndon Case Kendall Thomas Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Kendall Thomas, Rouge et Noir Reread: A Popular Constitutional History of the Angelo Herndon Case, 65 S. CAL. L. REV. 2599 (1992). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2177 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROUGE ET NOIR REREAD: A POPULAR CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY OF THE ANGELO HERNDON CASE KENDALL THOMAS* I. INTRODUCTION If the ruling and the oppressed elements in a population, if those who wish to maintain the status quo and those concerned to make changes, had, when they became articulate, the same philosophy, one might well be skeptical of its intellectual integrity. John Dewey' In 1932, Eugene Angelo Braxton Hemdon, a young Afro-Ameri- can 2 member of the Communist Party, U.S.A., was arrested in Atlanta and charged with an attempt to incite insurrection against that state's * Professor of Law, Columbia University. B.A. 1978, Yale University; J.D. 1983, Yale Law School. I would like to thank the many readers of early drafts of this Article for their helpful comments, as well as Worigia Bowman, Blondel Pinnock, and Mano Raju for their research assist- ance. -

Anti-Fascist League Set up Despite Coast Terror

DAILY WORKER. NEW YORK. SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 1935 Page 3 ANTI-FASCIST LEAGUE SET UP DESPITE COAST TERROR OFFICIALS, State Pardon Board | SOVIET WORKERS MAN ICEBOATS New Series on N.R.A. INSURANCE MOVE BOSSES, To Consider Case I To Begin on Monday LEGIONAIRES FAIL Os Phil Frankfeld I In the Daily Worker PUSHED IN STATES (Daily Worker Pittsburgh Bureau) PITTSBURGH, Pa., Feb. I. What does the “reorganiza- j :i: R. the The Pennsylvania State Pardons tion" of the N. A. by • ■M ‘f * Roosevelt government mean to TO PREVENT RALLY Board today notified the Frank- WESS. J AS HEARINGS OPEN ! the workers In the basic indus- feld Liberation Committee that g* the Board will consider pardon ic AvA-A i tries? What has the N. R. A. applications in the cases of Phil ■ j accomplished for the masses in « Jg % M orkers' Organizations. Epic Clubs, and M mpi m' A j the United States? These ques- Sixty-Two Workers Representing Many Groups Utopians, Frankfeld. Emma Brletic • ** Dan Benning on Feb. 20, and tions will be answered in a series ! of by Reeve, ill Coming Technocrats, Liberals Unite to Resist that the result of their "con- /MU articles Carl asso- Testify During Weeks Before | ciate editor of the Daily Worker, ( sideration’’ will be announced by - MuS&mk i * -. House Labor Attacks on Rights in Santa Monica Feb. 23. jtSjft 'yaw, f *,y^Bt^aK^sjc^waßSSe^^^c beginning Monday, Feb. 4. These Committee on | articles will take up specifically The letter states that in case r the situation in the steel, auto, j hearings the &!-' /.c>. -

Some Remarks on the Twentieth Anniversary of the C

SOME REMARKS ON THE TWENTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE C. P. U. S. A. BY EARL BROWDER HE twentieth anniversary of the lagged behind that of the other capi T Communist Party of the U.S.A. talist countries. This was especially occurs at a moment of world and na true of the political movement of the tional crisis. At such moments ad working class, and of its highest ex vanced mankind instinctively turns to pression, the socialist or communist a re-evaluation of its history, of the movement. It is only in the last road by which it came to the crisis twenty years that there has been an facing it, in order the better to equip American party expressly basing itself itself for the impending struggles upon Marxian theory, and only in which will determine future history. the last decade that this party has It is thus no mere formal duty if we, come to play a sustained and impor on our anniversary, tum our atten tant role in the life of the country. tion more seriously than ever before In approaching the task of working to a consideration of the history of out a detailed and systematic under our Party. standing of the history of the U.S.A., It was more than ninety years ago of the labor movement, and of the when Marx and Engels penned their Socialist and Communist movement, famous phrase-"a specter hovers over specifically of the Communist Party Europe, the specter of Communism." of the U.S.A., we have received a Since that time Communism has highly important stimulus and help grown into a world movement of de in the recently-published History of cisive importance for every country. -

Unemployment Relief and Social Insurance

()00273 loyment eliel and ocial Insuranee SOCIALIST lABOR The COlI EC InN Communist Party Program Against The Capitalist Program of arvation PrIce z; Hoover and the Boss Class Say STARVE in the midst of PLENTY. The Communist Party says FIGHT Against STARVATION. .LEADS FIGHT FOR Unemployment Insurance Free Medical Attention for Unemp oyed Free Gas, Electricity for Unemployed Free Milk for Starving Children ( 1 MARn~ WIIH GlER -th)~<1e:{2.. M~c.tt'. T:z' SUBSCRIPTION .IN EI/c.rzy ~Mo,.qT/lA'rIOl" RATES: ~Vt:.R Y 5TRII<t' One year __$6.00 Six months __ 3.00 ID!t,~~ NI'tft fhree months _ 1.50 '1.1'1 Two months _ 1.00 ~Z~:~~~ One month __ .50 ?; One month __ .50 ~ - ALl- Tt1f: <l'Jf I liMe In Boroughs of Manhattan and \? <' Bronx, N. Y. C.: One year __$8.00 Six months _ 4.50 Three months_ 2.25 T\ One month __ .75 DAILY WORKER 50 East 13th Street New York City TO THE WORKERS AND TOILING FARMERS OF AMERICA: President Hoover has announced the policy of the United States government on the question of unem ployment and farmers' relief. The sum of Hoover's policy is: The federal government will do nothing for the un employed. The 11,000,000 and more jobless workers, together with the millions of their families, are bru tally told at they must depend upon the "charity" 'of rich individuals for food and the park benches for shelter in the coming winter. For the admitted pur pose of smothering the demands of millions of hun gry and desperate workers, to confuse and divert this demand from the doors of the Congress which will convene on December 2nd, Hoover has appointed Wal ter S. -

JEANNETTE GABRIEL 'Natural Love for a Good Thing': the Struggle of the Unemployed Workers' Movement for a Government Jobs Programme, 1931-1942

JEANNETTE GABRIEL 'Natural Love for a Good Thing': The Struggle of the Unemployed Workers' Movement for a Government Jobs Programme, 1931-1942 in MATTHIAS REISS AND MATT PERRY (eds.), Unemployment and Protest: New Perspectives on Two Centuries of Contention (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011) pp. 111–116 ISBN: 978 0 199 59573 0 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 'Natural Love for a Good Thing': The Struggle of the Unemployed Workers' Movement for a Government Jobs Programme, 1931-1942 jEANNETTE GABRIEL The development of government work programmes in the 1930s has traditionally been viewed as a relatively smooth transition from the first, experimental Civil Works Administration (CWA) programme to the more long-term Works Projects Administration (WPA), with the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) filling in the gaps. However, this was a volatile period when it was not clear the unemployed would be given controver- sial government jobs as opposed to the more limited and long- standing policy of direct relie£ This brief time period, from the autumn of 1933 when CWA began until the summer of 1935 when WPA was instituted, is insignificant when viewed in terms of cal- endar months. -

Chicago Workers To

D \ILY WORKER, SATURDAY, 27, NEW YORK. JANUARY 1934 Page Three Chicago Workers to 17,000 Arizona CWA Crisis Hits Kid Hardest -tuaop* Police Shoot ißank and File Miners WorkersGetPayCut Meet Police Down Boy in FI av Lewis Machine Despite Reduce State CWA Pav Coal Strike 38 Per Cent al l MW A Convention Anthracite Picketing Ban on Feb. 5 Meeting PHOENIX. Ariz., Jan. 26. More ! than 17,000 C. W. A. workers in Ari- i Continues; Troopers zona have been given a pay slash by Resolutions elected as a member of the District the ! Indicate to Meet at recent Roosevelt announcement Launch Terror Board to avoid any discrimination on Jobless abandoning the C. W. A. program | W ide Opposition to the account of race, color or creed.” the ruling all Grant Park Relief Head Admits Since states that work- (Special Wire the Dailv There are a large number of Despite ers in cities of than 2.5C0 to Worker) Strikebreaking living less WILKES Pa., Clique resolutions demanding the immediate Effectiveness C.P. population will go on a 15-hcur week, BARRE, Jan. 26. Police Refusal of Police of Wilkes Barre and fa- release of the Scottsboro Boy*; practically all C. W. A. workers in shot (Continued Page 1) In Struggles I tally wounded Peter Dobranski, age from a resolution demanding a one day Relief Arizona will get a 50 per cent pay ; CHICAGO, 111., Jan. 36—Police 16, on the picket line at the South strike on May First for the free- cut; very few cities in the state have ! the fact that the membership twice Commissioner Allman yesterday in- Wilkes Barre Colliery early this mor- dom of Tom Mooney; a resolution (By Correspondent) over 2,500 population.