Amelia Bassano Lanier: a New Paradigm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Lady of the Merchant of Venice

3 The dark lady of The Merchant of Venice ‘The Sonnets of Shakespeare offer us the greatest puzzle in the history of English literature.’ So began the voyage of Alfred Leslie Rowse (1903–97) through the murky waters cloaking the identi- ties of four persons associated with the publication in 1609 of Shakespeare’s ‘sugared sonnets’: the enigmatic ‘Mr. W.H.’ cited in the forepages as ‘onlie begetter’ of the poems; the unnamed ‘fair youth’ addressed in sonnets 1–126; the ‘rival poet’ who surfaces and submerges in sonnets 78–86; and the mysterious ‘dark lady’ celebrated and castigated in sonnets 127–52.1 Doubtless, even as Thomas Thorpe’s edition was passing through George Eld’s press, London’s mice-eyed must have begun their search for the shadowy four; it has not slacked since. As to those nominated as ‘Mr. W.H.’, the list ranges from William Herbert to Henry Wroithesley (with initials reversed) to William Harvey (Wroithesley’s stepfather). In 1964 Leslie Hotson proposed one William Hatcliffe of Lincolnshire [!], while Thomas Tyrwitt, Edmond Malone, and Oscar Wilde all favoured a (fictional) boy actor, Willie Hughes. Among candidates for the ‘fair youth’, Henry Wroithesley, Earl of Southampton (1573–1624), appears to have outlasted all comers. Those proposed as the rival poet include Christopher Marlowe (more interested in boys than ladies dark or light); Samuel Daniel (Herbert’s sometime tutor);2 Michael Drayton, drinking partner of Jonson and Shakespeare; George Chapman, whose Seaven Bookes of the Iliades (1598) were a source for Troilus and Cressida; and Barnabe Barnes, lampooned by Nashe as ‘Barnaby Bright’ in Have with you to Saffron-Walden. -

Cultural Aspects in Shakespeare's Merchant Of

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.3 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed Journal 2016 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE CULTURAL ASPECTS IN SHAKESPEARE’S MERCHANT OF VENICE Najma Begum (Lecturer in English, SRR & CVR Govt. Degree College, Vijayawada.) [email protected] ABSTRACT It is desirable to know the cultural context of any given text to understand it better. It is more so when the text is distanced in terms of space and time. Likewise to understand the famous Shakespearean comedy, Merchant of Venice, we need to understand the cultural background of society in which the play was created. So the present paper takes it as a task to explain the cultural aspects in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice Keywords: Culture, Society, Jews, Elizabethan times. Citation: APA Begum,N. (2016) Cultural Aspects in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.Veda’s Journal of English Language and Literature- JOELL, 3(4), 100-102. MLA Begum, Najma. “Cultural Aspects in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.” Veda’s Journal of English Language and Literature-JOELL 3.4(2016):100-102. © Copyright VEDA Publication LOVE husband. Similarly, Antonoio clearly loves Bassanio( Love is the key theme in the book. There are whether in a romantic manner or not) and he many loving relationships in this play and not all are ultimately must subordinate his love for Bassanio to the type that involved the love that a man has for a Portia’s more formal marriage with him. Love is woman, or vice-versa. Bassanio and Portia, Jessica regulated, sacrificed, betrayed, and generally built on and Lorenzo and Gratiano and Nerissa are all types of rocky foundations in the play. -

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

Understanding the Gender Complexities of Shakespeare Dr Peter D Matthews

Understanding the Gender Complexities of Shakespeare Dr Peter D Matthews Introduction The dramatists of Shakespeare are often characterized as being feminists because of the frankness of Cordelia in King Lear, the shrewdness or Portia in The Merchant of Venice, and the psychological manipulation of Volumnia in Coriolanus. For over four hundred years we have performed the incredible representations of men and women and their various roles and responsibilities in society during the latter Renaissance period, where male actors would have pretended to be the character of Viola in Twelfth Night, while pretending to be her brother Sebastian, as a male character. This seems to be quite a complex idea in the latter sixteenth century. Some scholars have suggested that feminism did not exist during this era. I will prove in this paper that these assertions are fatally flawed – feminism was alive and well during that era. However, the dramatists of Shakespeare were not feminists, per say, they were in fact Master Kabbalists teaching the gender complexities of the ancient Zohar and the Tree of Life, where one can allow ego to ruin one’s life, or shut down our reactive system and be transformed to the supernal (heavenly) realm of perfection beyond human perception and repair the world. Historical Background With the humanist movements in Europe, particularly Italy, during the 15th and 16th centuries many women rose to study philosophy of women and positions of power. One such document was the ‘Querelle des Femmes’ (The Woman Question) that began a movement circa 1500, followed by a lectured on the ‘Virtues of the Female Sex’ by the learned philosopher Heinrich Agrippa of Nettesheim in 1509. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <Em>Othello</Em>

Marquette University From the SelectedWorks of Sarah E. Thompson 2012 "I Am No Strumpet": Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <em>Othello</em> Sarah E. Thompson, Marquette University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/sarah_thompson/1/ 1 Sarah Thompson English 6220 December 12, 2012 “I Am No Strumpet”: Bianca and Cassio’s Relationship in Othello Throughout the critical history of Shakespeare’s Othello, audiences and critics alike have identified love and sexuality as major themes of the play. Indeed, there are many who would argue that the play as a whole is an examination of heterosexual relationships, with all the concerns, such as sexual anxieties, gender inequalities, and emotional struggles that accompany this subject. Discussions of Othello’s portrayal of the relationships between men and women integrate any number of other facets of literary study, such as the psychological factors that shape the relationships of Othello and Desdemona or Iago and Emilia, or the cultural expectations for gender and marriage during the Renaissance, and how these expectations are both upheld and critiqued in Othello, or how the genre elements of sex, or love, tragedies influence the play’s action and the audience’s expectations for the play. Many critics who examine the married relationships focus on the feminine roles that Desdemona and Emilia fill or challenge, while others study the masculine perspectives of these relationships, and seek to explore what prompts Iago’s seeming “hatred of his wife and all women,”1 or Othello’s obsession with Desdemona’s sexuality, and his self-doubts, frequently linked to his age and racial status, about his ability to satisfy her in their relationship. -

Reading Female Agency in the Merchant of Venice1

Defrauding Daughters Turning Deviant Wives? Reading Female Agency in The Merchant of Venice 1 Nicoleta Cinpoe ş University of Worcester ABSTRACT Brabantio’s words “Look to her, Moor, if thou hast eyes to see:| She has deceived her father, and may thee” (Othello , 1.3.292–293) warn Othello about the changing nature of female loyalty and women’s potential for deviancy. Closely examining daughters caught in the conflict between anxious fathers and husbands-to- be, this article departs from such paranoid male fantasy and instead sets out to explore female deviancy in its legal and dramatic implications with reference to Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice . I will argue that Portia’s and Jessica’s struggle to evade male subsidiarity results in their conscious positioning themselves on the verge of illegality. Besides occasioning productive exploration of marriage, law and justice within what Morss (2007:183) terms “the dynamics of human desire and of social institutions,” I argue that female agency, seen as temporary deviancy and/or self-exclusion, reconfigures the male domain by affording the inclusion of previous outsiders (Antonio, Bassanio and Lorenzo) . KEYWORDS : The Merchant of Venice ; commodity/ commodification; subsidiarity; bonds/binding; marriage code versus friendship code; defrauding; deviancy; agency; conveyancing; (self)exclusion. 1 My reading of The Merchant of Venice with a view to agency that reconfigures the social structures is indebted to and informed by Margaret S. Archer’s work on structure and agency, especially -

CONTENTS Editorial I Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

VOL. LVI. No. 173 PRICE £1 函°N加少 0 December, 1973 CONTENTS Editorial i Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford ... 11 Othello ... 17 Ex Deo Nascimur 31 Bacon's Belated Justice 35 Francis Bacon*s Pictorial Hallmarks 66 From the Archives 81 Hawk Versus Dove 87 Book Reviews 104 Correspondence ... 111 © Published Periodically LONDON: Published by The Francis Bacon Society IncorporateD at Canonbury Tower, Islington, London, N.I, and printed by Lightbowns Limited, 72 Union Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight. THE FRANCIS BACON SOCIETY (INCORPORATED) Among the Objects for which the Society is established, as expressed in the Memorandum of Association, are the following 1. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the study of the works of Francis Bacon as philosopher, statesman and poet; also his character, genius and life; his- — . influence: — £1._ _ — — — on his1" — own and J succeeding— J : /times, 〜— —and the tendencies cfand」 v*results 否 of his writing. 2. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the general study of the evidence in favour of Francis Bacon's authorship of the plays commonly ascribed to Shakespeare, and to investigate his connection with other works of the Elizabethan period. Officers and Council: Hon, President: Cmdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Past Hon, President: Capt. B, Alexander, m.r.i. Hon. Vice-Presidents: Wilfred Woodward, Esq. Roderick L. Eagle, Esq. Council: Noel Fermor, Esq., Chairman T. D. Bokenham, Esq., Vice-Chairman Cmdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Nigel Hardy, Esq. J. D. Maconachie, Esq. A. D. Searl, Esq. Sidney Filon, Esq. Austin Hatt-Arnold, Esq. Secretary: Mrs. D. -

![English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5082/english-202-in-italy-text-2-official-course-title-english-280-1-shakespeare-the-merchant-of-world-literature-i-dr-1175082.webp)

English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr

Text 2: English 202 in Italy [Official course title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, The Merchant of World Literature I Venice Dr. Gavin Richardson EDITION: Any; the Folger Shakespeare is recommended. READING JOURNAL: In a separate document, write 3-5 thoughtful sentences in response to each of these reading journal prompts: 1. Act 1 scene 3 features the crucial loan scene. At this point, do you think Shylock is serious about the pound of flesh he demands as collateral for Antonio’s loan for Bassanio? Why or why not? 2. In 2.3. Jessica leaves her (Jewish) father for her (Christian) husband. Does her desertion create sympathy for Shylock? Or do we cheer her action? Is her “conversion” an uplifting one? 3. Shylock’s speech in 3.1.58–73 may be the most famous of the entire play. After reading this speech, review Ann Barton’s comments on the performing of Shylock and write a paragraph on what you think Shylock means to Shakespeare: “Shylock is a closely observed human being, not a bogeyman to frighten children in the nursery. In the theatre, the part has always attracted actors, and it has been played in a variety of ways. Shylock has sometimes been presented as the devil incarnate, sometimes as a comic villain gabbling absurdly about ducats and daughters. He has also been sentimentalized as a wronged and suffering father nobler by far than the people who triumph over him. Roughly the same range of interpretation can be found in criticism on the play. Shakespeare’s text suggests a truth more complex than any of these extremes.” 4. -

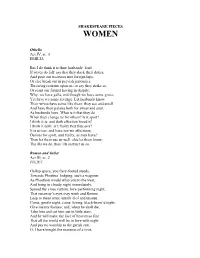

SHAKESPEARE PIECES Othello Act IV, Sc. 3 EMILIA but I Do Think It Is

SHAKESPEARE PIECES WOMEN Othello Act IV, sc. 3 EMILIA But I do think it is their husbands’ fault If wives do fall: say that they slack their duties, And pour our treasures into foreign laps, Or else break out in peevish jealousies, Throwing restraint upon us; or say they strike us, Or scant our former having in despite; Why, we have galls, and though we have some grace, Yet have we some revenge. Let husbands know Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell And have their palates both for sweet and sour, As husbands have. What is it that they do When they change us for others? Is it sport? I think it is: and doth affection breed it? I think it doth: is’t frailty that thus errs? It is so too: and have not we affections, Desires for sport, and frailty, as men have? Then let them use us well: else let them know, The ills we do, their ills instruct us so. Romeo and Juliet Act III, sc. 2 JULIET Gallop apace, you fiery-footed steeds, Towards Phoebus’ lodging: such a wagoner As Phaethon would whip you to the west, And bring in cloudy night immediately. Spread thy close curtain, love-performing night, That runaway’s eyes may wink and Romeo Leap to these arms, untalk’d of and unseen. Come, gentle night, come, loving, black-brow’d night, Give me my Romeo; and, when he shall die, Take him and cut him out in little stars, And he will make the face of heaven so fine That all the world will be in love with night And pay no worship to the garish sun. -

The Merchant of Venice (C

The Merchant of Venice (c. 1596) Contextual information Quotes from The Merchant of Venice Giovanni’s collection of stories, Il Pecorone (1558), was a key source for The Merchant of Venice. In one tale, a Venetian merchant borrows money to give his godson, but the Jewish moneylender demands a pound of flesh if the bond is not repaid on time. The young man uses the money to woo a Lady of Belmont – a ruthless widow who cheats her lovers by drugging them. Shakespeare introduces the love test involving a choice of caskets Explore Il Pecorone, an Italian as part of Bassanio’s suit to Portia. source for The Merchant of Venice Shakespeare took his wooing scene from the ancient tale of ‘Three Caskets’ which tells of a young girl who must prove her love for the emperor’s son by choosing from three vessels made of gold, silver and lead. Shakespeare gives the choice to three View a golden casket from men rather than a woman. Venice Christopher Marlowe’s play, The Jew of Malta (c. 1592), is a tale of violent conflict between Christians, Jews and Turks which seems to have influenced Shakespeare. The hero-villain, Barabas a wealthy Jew, has a cruel but intoxicating desire for money and revenge. When Barabas’ daughter Abigail elopes with a Christian, he shouts ‘O my girle, / My gold, my fortune, my felicity’. Ultimately, The Jew of he destroys himself in his own trap as the Explore Marlowe's Malta Christians deny him mercy. Queen Elizabeth I’s Jewish physician, Doctor Lopez was tried and executed for allegedly plotting to kill the Queen in 1594.