Understanding the Gender Complexities of Shakespeare Dr Peter D Matthews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Aspects in Shakespeare's Merchant Of

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.3 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed Journal 2016 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE CULTURAL ASPECTS IN SHAKESPEARE’S MERCHANT OF VENICE Najma Begum (Lecturer in English, SRR & CVR Govt. Degree College, Vijayawada.) [email protected] ABSTRACT It is desirable to know the cultural context of any given text to understand it better. It is more so when the text is distanced in terms of space and time. Likewise to understand the famous Shakespearean comedy, Merchant of Venice, we need to understand the cultural background of society in which the play was created. So the present paper takes it as a task to explain the cultural aspects in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice Keywords: Culture, Society, Jews, Elizabethan times. Citation: APA Begum,N. (2016) Cultural Aspects in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.Veda’s Journal of English Language and Literature- JOELL, 3(4), 100-102. MLA Begum, Najma. “Cultural Aspects in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.” Veda’s Journal of English Language and Literature-JOELL 3.4(2016):100-102. © Copyright VEDA Publication LOVE husband. Similarly, Antonoio clearly loves Bassanio( Love is the key theme in the book. There are whether in a romantic manner or not) and he many loving relationships in this play and not all are ultimately must subordinate his love for Bassanio to the type that involved the love that a man has for a Portia’s more formal marriage with him. Love is woman, or vice-versa. Bassanio and Portia, Jessica regulated, sacrificed, betrayed, and generally built on and Lorenzo and Gratiano and Nerissa are all types of rocky foundations in the play. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Reading Female Agency in the Merchant of Venice1

Defrauding Daughters Turning Deviant Wives? Reading Female Agency in The Merchant of Venice 1 Nicoleta Cinpoe ş University of Worcester ABSTRACT Brabantio’s words “Look to her, Moor, if thou hast eyes to see:| She has deceived her father, and may thee” (Othello , 1.3.292–293) warn Othello about the changing nature of female loyalty and women’s potential for deviancy. Closely examining daughters caught in the conflict between anxious fathers and husbands-to- be, this article departs from such paranoid male fantasy and instead sets out to explore female deviancy in its legal and dramatic implications with reference to Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice . I will argue that Portia’s and Jessica’s struggle to evade male subsidiarity results in their conscious positioning themselves on the verge of illegality. Besides occasioning productive exploration of marriage, law and justice within what Morss (2007:183) terms “the dynamics of human desire and of social institutions,” I argue that female agency, seen as temporary deviancy and/or self-exclusion, reconfigures the male domain by affording the inclusion of previous outsiders (Antonio, Bassanio and Lorenzo) . KEYWORDS : The Merchant of Venice ; commodity/ commodification; subsidiarity; bonds/binding; marriage code versus friendship code; defrauding; deviancy; agency; conveyancing; (self)exclusion. 1 My reading of The Merchant of Venice with a view to agency that reconfigures the social structures is indebted to and informed by Margaret S. Archer’s work on structure and agency, especially -

![English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5082/english-202-in-italy-text-2-official-course-title-english-280-1-shakespeare-the-merchant-of-world-literature-i-dr-1175082.webp)

English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr

Text 2: English 202 in Italy [Official course title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, The Merchant of World Literature I Venice Dr. Gavin Richardson EDITION: Any; the Folger Shakespeare is recommended. READING JOURNAL: In a separate document, write 3-5 thoughtful sentences in response to each of these reading journal prompts: 1. Act 1 scene 3 features the crucial loan scene. At this point, do you think Shylock is serious about the pound of flesh he demands as collateral for Antonio’s loan for Bassanio? Why or why not? 2. In 2.3. Jessica leaves her (Jewish) father for her (Christian) husband. Does her desertion create sympathy for Shylock? Or do we cheer her action? Is her “conversion” an uplifting one? 3. Shylock’s speech in 3.1.58–73 may be the most famous of the entire play. After reading this speech, review Ann Barton’s comments on the performing of Shylock and write a paragraph on what you think Shylock means to Shakespeare: “Shylock is a closely observed human being, not a bogeyman to frighten children in the nursery. In the theatre, the part has always attracted actors, and it has been played in a variety of ways. Shylock has sometimes been presented as the devil incarnate, sometimes as a comic villain gabbling absurdly about ducats and daughters. He has also been sentimentalized as a wronged and suffering father nobler by far than the people who triumph over him. Roughly the same range of interpretation can be found in criticism on the play. Shakespeare’s text suggests a truth more complex than any of these extremes.” 4. -

The Merchant of Venice (C

The Merchant of Venice (c. 1596) Contextual information Quotes from The Merchant of Venice Giovanni’s collection of stories, Il Pecorone (1558), was a key source for The Merchant of Venice. In one tale, a Venetian merchant borrows money to give his godson, but the Jewish moneylender demands a pound of flesh if the bond is not repaid on time. The young man uses the money to woo a Lady of Belmont – a ruthless widow who cheats her lovers by drugging them. Shakespeare introduces the love test involving a choice of caskets Explore Il Pecorone, an Italian as part of Bassanio’s suit to Portia. source for The Merchant of Venice Shakespeare took his wooing scene from the ancient tale of ‘Three Caskets’ which tells of a young girl who must prove her love for the emperor’s son by choosing from three vessels made of gold, silver and lead. Shakespeare gives the choice to three View a golden casket from men rather than a woman. Venice Christopher Marlowe’s play, The Jew of Malta (c. 1592), is a tale of violent conflict between Christians, Jews and Turks which seems to have influenced Shakespeare. The hero-villain, Barabas a wealthy Jew, has a cruel but intoxicating desire for money and revenge. When Barabas’ daughter Abigail elopes with a Christian, he shouts ‘O my girle, / My gold, my fortune, my felicity’. Ultimately, The Jew of he destroys himself in his own trap as the Explore Marlowe's Malta Christians deny him mercy. Queen Elizabeth I’s Jewish physician, Doctor Lopez was tried and executed for allegedly plotting to kill the Queen in 1594. -

Rodrigo Beilfuss

RODRIGO BEILFUSS ADDRESS: 26 Nethercott Dr | Stratford, ON | N5A 7G4 MOBILE: 1‐204‐806‐7054 | EMAIL: [email protected] | Union: CAEA | website: rodrigobeilfuss.com HEIGHT: 6’‐2” WEIGHT: 185 LBS. HAIR COLOUR: DARK BROWN EYE COLOUR: HAZEL VOICE: BARITONE THEATRE – ACTING/DIRECTING (selected) The Aeneid Fellow Countryman & Ensemble Stratford Festival / Keira Loughran All My Sons Frank Lubey Stratford Festival / Martha Henry Shakespeare’s Macbeth Young Siward & Ensemble Stratford Festival / Antoni Cimolino Shakespeare’s King Richard III Clarence / Rivers / Bishop of Ely Birmingham Conservatory/ Martha Henry Six Characters in Search of an Author The Producer Birmingham Conservatory/ Chris Newton Sea Wall Alex (Co‐Director) Theatre by the River / Kendra Jones Shakespeare’s Hamlet Hamlet Bravura Theatre / Sarah Constible Private Lives (Assistant Director) RMTC / Krista Jackson Cock & Bull (two plays in rep) (Director) TBTR (Theatre by the River) La Belle Laide (silent movement piece) Man (2014 Winnipeg Fringe) Lady of the Lake / Jacquie Loewen Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors Angelo / Merchant / Chicken‐Man S.I.R. / Ron Jenkins About Love & Champagne (Author / Solo Performer) RMTC ChekhovFest / Fancy Bred Theatre Venus in Fur (Co‐Director) Tristan Bates Theatre (UK) Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure Duke Vincentio Linbury Studio (UK) / Bill Alexander The Double Dealer Ned Careless LAMDA / Rodney Cottier The Changeling Vermandero LAMDA / Will Oldroyd Lungs (Canadian Premiere) (Director – 2012 Winnipeg Fringe) Theatre by the River (TBTR) -

The Merchant of Venice Teacher Pack 2015

- 1 - Registered charity no. 212481 © Royal Shakespeare Company ABOUT THIS PACK This pack supports the RSC’s 2015 production of The Merchant of Venice, directed by Polly Findlay, which opened on 14th May at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. The activities provided are specifically designed to support KS3-4 students attending the performance. ABOUT YOUNG SHAKESPEARE NATION Over the next six years, the RSC will stage the 36 plays that make up the First Folio of Shakespeare’s work. RSC Education invites you to join us on this inspirational journey in a new initiative called Young Shakespeare Nation. Whether you want to teach a new play or teach in a new way, Young Shakespeare Nation can give you the tools and resources you need. Find inspiration online with images, video’s, more teacher packs and resources at www.rsc.org.uk/education Participate in our schools’ broadcast series, continuing with Henry V on 19 November 2015 Explore a new text or a new way of teaching through our CPD programme Try one of our range of courses for teachers and students in Stratford-upon-Avon. Find out more at www.rsc.org.uk/education These symbols are used throughout the pack: CONTENTS READ Notes from the production, About this Pack Page 2 background info or extracts Exploring the Story Page 3 ACTIVITY The Republic of Venice Page 4 A practical or open space activity Status and Wealth Page 6 WRITE Hazarding Page 8 A classroom writing or discussion activity Justice and the Resolution Page 10 Resources Page 11 LINKS Useful web addresses and research tasks - 2 - Registered charity no. -

Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96;

. MC0111117 VESUI17 Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96; AUTHOR McLean, Ardrew M. TITLE . ,A,Shakespeare: Annotated BibliographiesendAeaiaGuide 1 47 for Teachers. .. INSTIT.UTION. NIttional Council of T.eachers of English, Urbana, ..Ill. .PUB DATE- 80 , NOTE. 282p. AVAILABLe FROM Nationkl Coun dil of Teachers,of Englishc 1111 anyon pa., Urbana, II 61.801 (Stock No. 43776, $8.50 member, . , $9.50 nor-memberl' , EDRS PRICE i MF011PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Biblioal7aphies: *Audiovisual Aids;'*Dramt; +English Irstruction: Higher Education; 4 *InstrUctioiral Materials: Literary Criticism; Literature: SecondaryPd uc a t i on . IDENTIFIERS *Shakespeare (Williaml 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this annotated b'iblibigraphy,is to identify. resou'rces fjor the variety of approaches tliat teachers of courses in Shakespeare might use. Entries in the first part of the book lear with teaching Shakespeare. in secondary schools and in college, teaching Shakespeare as- ..nerf crmance,- and teaching , Shakespeare with other authora. Entries in the second part deal with criticism of Shakespearear films. Discussions of the filming of Shakespeare and of teachi1g Shakespeare on, film are followed by discu'ssions 'of 26 fgature films and the,n by entries dealing with Shakespearean perforrances on televiqion: The third 'pax't of the book constituAsa glade to avAilable media resources for tlip classroom. Ittries are arranged in three categories: Shakespeare's life'and' iimes, Shakespeare's theater, and Shakespeare 's plam. Each category, lists film strips, films, audi o-ca ssette tapes, and transparencies. The.geteral format of these entries gives the title, .number of parts, .grade level, number of frames .nr running time; whether color or bie ack and white, producer, year' of .prOduction, distributor, ut,itles of parts',4brief description of cOntent, and reviews.A direCtory of producers, distributors, ard rental sources is .alst provided in the 10 book.(FL)- 4 to P . -

Rethinking Shylock's Tragedy: Radford's Critique of Anti-Semetism in the Merchant of Venice

Volume 28 Number 3 Article 8 4-15-2010 Rethinking Shylock's Tragedy: Radford's Critique of Anti-Semetism in The Merchant of Venice Frank P. Riga (retired) Canisius College, Buffalo, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Riga, Frank P. (2010) "Rethinking Shylock's Tragedy: Radford's Critique of Anti-Semetism in The Merchant of Venice," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 28 : No. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol28/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico • Postponed to: July 30 – August 2, 2021 Abstract Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice is not usually thought of as one of his more mythically resonant plays (aside from the Belmont casket scene), yet it is ultimately based on prevailing contemporary Christian myths about Jews and the way these myths defined Christians’ beliefs about themselves. This paper examines film director Michael Radford’s masterful use of myths and symbolism in his production of this play. -

The Merchant of Venice Teacher Sample

CONTENTS How to Use This Study Guide With the Text .........4 QUIZZES & ANSWER KEY 107 Notes & Instructions to Teacher ...............................5 Quiz: Act One .....................................................108 Taking With Us What Matters ..................................7 Quiz: Act Two .....................................................112 Four Stages to the Central One Idea .........................9 Quiz: Act Three ..................................................117 How to Mark a Book .................................................11 Quiz: Act Four ....................................................123 Introduction ...............................................................12 Quiz: Act Five .....................................................127 Basic Features & Background ..................................14 Quiz: Act One — Answer Key .........................131 Quiz: Act Two — Answer Key .........................135 ACT 1 15 Quiz: Act Three — Answer Key ......................140 Pre-Grammar | Preparation ...............................16 Quiz: Act Four — Answer Key ........................145 Grammar | Presentation .....................................17 Quiz: Act Five — Answer Key .........................149 Logic | Dialectic ...................................................22 Rhetoric | Expression ..........................................24 ACT 2 31 Pre-Grammar | Preparation ...............................32 Grammar | Presentation .....................................33 Logic | Dialectic ...................................................39 -

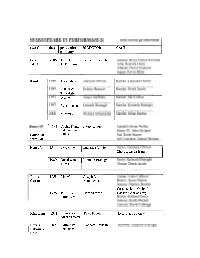

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare

The Merchant of Venice Thou wilt not only loose the forfeiture, by William Shakespeare But, touch'd with human gentleness and love, (http://www.online-literature.com/shakespeare/merchant/18/) Forgive a moiety of the principal; Glancing an eye of pity on his losses, Act 4, Scene I That have of late so huddled on his back, Enow to press a royal merchant down And pluck commiseration of his state SCENE I. Venice. A court of justice. From brassy bosoms and rough hearts of flint, From stubborn Turks and Tartars, never train'd Enter the DUKE, the Magnificoes, ANTONIO, To offices of tender courtesy. BASSANIO, GRATIANO, SALERIO, and others We all expect a gentle answer, Jew. DUKE SHYLOCK What, is Antonio here? I have possess'd your grace of what I purpose; And by our holy Sabbath have I sworn ANTONIO To have the due and forfeit of my bond: Ready, so please your grace. If you deny it, let the danger light Upon your charter and your city's freedom. DUKE You'll ask me, why I rather choose to have I am sorry for thee: thou art come to answer A weight of carrion flesh than to receive A stony adversary, an inhuman wretch Three thousand ducats: I'll not answer that: uncapable of pity, void and empty But, say, it is my humour: is it answer'd? From any dram of mercy. What if my house be troubled with a rat And I be pleased to give ten thousand ducats ANTONIO To have it baned? What, are you answer'd yet? I have heard Some men there are love not a gaping pig; Your grace hath ta'en great pains to qualify Some, that are mad if they behold a cat; His rigorous course; but since he stands obdurate And others, when the bagpipe sings i' the nose, And that no lawful means can carry me Cannot contain their urine: for affection, Out of his envy's reach, I do oppose Mistress of passion, sways it to the mood My patience to his fury, and am arm'd Of what it likes or loathes.