The Status of the Cirl Bunting in the UK in 2009 Andrew Stanbury, Mary Davies, Phil Grice, Richard Gregory and Simon Wotton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

i procp:edings of uxited states national :\[uset7m. 359 23498 g. D. 13 5 A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; 0. 31 ; B. S. Leiigtli ICT millime- ters. GGGl. 17 specimeus. St. Michaels, Alaslai. II. M. Bannister. a. Length 210 millimeters. D. 13; A. 14; V. 3; P. 33; C— ; B. 8. h. Length 200 millimeters. D. 14: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C— ; B. 8. e. Length 135 millimeters. D. 12: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C. 30; B. 8. The remaining fourteen specimens vary in length from 110 to 180 mil- limeters. United States National Museum, WasJiingtoiij January 5, 1880. FOURTBI III\.STAI.:HEIVT OF ©R!VBTBIOI.O«ICAI. BIBI.IOCiRAPHV r BE:INC} a Jf.ffJ^T ©F FAUIVA!. I»l.TjBf.S«'ATI©.\S REff,ATIIV« T© BRIT- I!§H RIRD!^. My BR. ELS^IOTT COUES, U. S. A. The zlppendix to the "Birds of the Colorado Yalley- (pp. 507 [lJ-784 [218]), which gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to North American Birds, is to be considered as the first instalment of a "Uni- versal Bibliography of Ornithology''. The second instalment occupies pp. 230-330 of the " Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories 'V Yol. Y, No. 2, Sept. G, 1879, and similarly gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to the Birds of the rest of America.. The.third instalment, which occnpies the same "Bulletin", same Yol.,, No. 4 (in press), consists of an entirely different set of titles, being those belonging to the "systematic" department of the whole Bibliography^ in so far as America is concerned. -

Scottish Birds

SB 30(2) COV 27/5/10 10:55 Page 1 The pair of Ptarmigan were roosting either side of a PhotoSP T boulder, and observing them for a while, they didn’t Plate 155. On a wintery day© in March 2010 I drove move. I decided to move a little bit closer to try and to the Cairngorms to record any birds I might see. capture a picture and I did this every five minutes or SCOTTISH There was snow at 1000 feet, and the mountain I so until I got to a decent distance for the 400 mm decided to climb was not far from thousands of lens. The picture I believe gives a real feeling to the skiers. I encountered Red Grouse at 1500 feet and extreme habitat in which Ptarmigan exist. I backed just a little bit higher at c. 2000 feet I came across off and left them to roost in peace. my first Ptarmigan. There was also a pair slightly BIRDS higher at c. 2900 feet. For people who are interested in camera gear, I used a Canon 40D, 400 mm lens and a Bushawk On my climb I also found foot prints of Mountain shoulder mount. Volume 30 (2) 30 (2) Volume Hare and more grouse. I’m sure the Ptarmigan had been forced lower down the hill to feed, as there John Chapman was so much snow cover and on the tops it must (www.johnchapmanphotographer.co.uk) have been -15°C the night before. Scottish Birds June 2010 published by the SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS’ CLUB Featuring the best images posted on the SOC website each quarter, PhotoSpot will present stunning portraits as well as record shots of something unique, accompanied by the story behind the photograph and the equipment used. -

XVIII. Observations on Some Species of British Quadrupeds, Birds, and Fishes

xtTTII.Obsewations 01) some Species of' British Quadrupeds, Birds, and Fides. By George .nhtagt(, Esq. F. L.S. Read December 20, 1803, Toa society founded on so libcral a basis as the Linnean Society there needs no introduction to the miscellaneous witings of an individual, whose object can only be the diffusion of knowledge on partial subjects of natural history. With this view I beg leave to lay before the Society the fol- lowing observations on a few species of British birds whose his- tory appears to be imperfectly known; together with a few addi- tional reinarks on two of our smallest quadrupeds; and a descrip- tion of a beautiful fish, the Cepola descem, hitherto? I believe,. not iioticed on our coast; and of two other rare species. I-IARVEST &!fOUSE. hIus Messorius.. Shaw Xool. ii. p. G2.jg. vignett.e. Mus rninutus. Gmel. Syt. p. 130. S.? IIarvest &use. Br. Xool. i. y. 107. Pennant Quadr. ii. p. 384. White Seh. p. 33. 39. This elegant little species of mouse, first noticed by Rlr. V'hitc as inhabiiing the corn-fields and ricks about Selborn, and, through his conirnunication, first made public by Mr. Pennant as indigenous to England, is by no means confined to I-Iamp- shire; for we well renieinber it was common in t.he inore cliani- paign parts of Wiltshire in our punger days, and previous to the disco very discovery of it by RTr. IVhite : and we liarc si1ic.c thmc juvenilc days found it in other parts of the saine county, in Glouccstcr- shire contiguous, and in the south of' Devonsliire. -

Mathew, M A, a Revised List of the Birds of Somerset, Part II, Volume 39

9 IRetHseO Ht0t of tfce T6ttO0 of Somerset BY THE REV. MURRAY A. MATHEW, M.A., F.L.S. Vicar of Buckland Dinham, Member of the British Ornitho- logists' Union, and one of the authors of" The Birds of DevonT WHEN Mr. Cecil Smith published his Birds of Somerset, in 1869, he was able to record but 217 species, to which he subsequently added ten others in a list contributed by him to Vol. xvi of the Transactions of the Somerset Archaaological and Natural History Society (for 1870), thus bringing the total number of birds for Somerset to 227. But even this number appears inadequate to repre- sent the Ornis of so large a county as Somerset, when it is compared with the lists which have been made out for the adjoining counties. Thus for Wiltshire, a county which comes far behind Somerset in geographical importance, as it possesses no coast line, the Rev. A. Smith was able to . C. enumerate 235 species ; in Dorsetshire, Col. Mansel-Pleydell, as was to be expected, had a fuller list, numbering 254 species, to which we are able to add three others, thus bringing the Dorsetshire county birds to a total of 257 ; while for Devon- shire, which has a sea frontage both on the north and south, as many as 300 species can be claimed. With the wild tract of Exmoor Forest and its beautiful fringe of woods ; with the Quantocks, the Blagdon Hills, the Mendip and other hills ; with the curious peat-moor district, occupying the centre of ; A Revised List of the Birds of Somerset. -

Identification of Pine Bunting T

Identification of Pine Bunting Daniele Occhiato he nominate subspecies of Pine Bunting tion between the two species in areas of sym- T Emberiza leucocephalos leucocephalos breeds patry on their Siberian breeding grounds. First- in a large part of Siberia from the western slopes generation hybrids, especially males, are gene- of the Ural (55° E) east to the Pacific, including rally distinctive and do not lead to confusion. Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands (c 155° E). It However, such hybrids are fertile, and back- ranges north to the Arctic Circle (66° N) and crosses with members of one or the other spe- south to northern Mongolia (50° N); a disjunct cies, or with other hybrids, lead to individuals in population breeds further south in the Altai, which evidence of hybridization is even more Tarbagatay, Ala Tau and Tien Shan mountain diluted, and often very difficult to detect in the ranges (45° N). A geographically isolated and field. In some cases, only careful in-hand exami- apparently sedentary subspecies, E l fronto, nation can reveal such hybrid characters. For breeds in northern Qinghai and Gansu prov- example, a study by Eugeny Panov (in Bradshaw inces, China (Cramp & Perrins 1994, Byers et al & Gray 1993) revealed that out of 239 adult 1995). The migratory nominate subspecies win- male Pine Bunting x Yellowhammer hybrids ters mostly in Afghanistan, Pakistan, north-west- studied in the hand in western Siberia, as many ern India, Nepal and northern China; less impor- as 58 were only identifiable as such by the yel- tant wintering areas include northern Iran, the low lesser underwing-coverts. -

RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where Science Comes to Life

RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where science comes to life Contents Knowing 2 Introducing the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science and an explanation of how and why the RSPB does science. A decade of science at the RSPB 9 A selection of ten case studies of great science from the RSPB over the last decade: 01 Species monitoring and the State of Nature 02 Farmland biodiversity and wildlife-friendly farming schemes 03 Conservation science in the uplands 04 Pinewood ecology and management 05 Predation and lowland breeding wading birds 06 Persecution of raptors 07 Seabird tracking 08 Saving the critically endangered sociable lapwing 09 Saving South Asia's vultures from extinction 10 RSPB science supports global site-based conservation Spotlight on our experts 51 Meet some of the team and find out what it is like to be a conservation scientist at the RSPB. Funding and partnerships 63 List of funders, partners and PhD students whom we have worked with over the last decade. Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) Conservation rooted in know ledge Introduction from Dr David W. Gibbons Welcome to the RSPB Centre for Conservation The Centre does not have a single, physical Head of RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Science. This new initiative, launched in location. Our scientists will continue to work from February 2014, will showcase, promote and a range of RSPB’s addresses, be that at our UK build the RSPB’s scientific programme, helping HQ in Sandy, at RSPB Scotland’s HQ in Edinburgh, us to discover solutions to 21st century or at a range of other addresses in the UK and conservation problems. -

Checklist of Suffolk Birds

Suffolk Bird Checklist status up to and including 2001 records (2002 & 2003 where stated) - not including BOURC category E R = records considered by BBRC r = records considered by SORC, requiring full descriptions see end of list for Category D and abundance codes red-throated diver common winter visitor and passage migrant, rare inland black-throated diver uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant, rare inland great northern diver uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant yellow (white)-billed diver R accidental, 3 records; 1852, 1978 and 1994 little grebe locally common resident, passage migrant and winter visitor great crested grebe locally common resident, passage migrant and winter visitor red-necked grebe uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant, mostly coastal slavonian grebe uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant, mostly coastal black-necked grebe uncommon winter visitor and passage migrant northern fulmar fairly common summer visitor and passage migrant Cory's shearwater r very rare (autumn) passage migrant; 28 records of 37 individuals, all post 1973 great shearwater r accidental, 6 records; 3 post 1950 sooty shearwater uncommon autumn migrant Manx shearwater uncommon passage migrant, mainly autumn Balearic shearwater r very rare passage migrant, 9 records, all since 1998 Leach's storm petrel r scarce passage migrant European storm petrel r very rare passage migrant, 28 individuals since 1950 northern gannet common offshore passage migrant great cormorant locally common passage migrant and winter visitor, a few oversummer -

Bird Report 2015 West Bexington and Cogden

West Bexington and Cogden Bird Report 2015 BIRD NOTES WEST BEXINGON AND COGDEN 2015 Mike Morse and Alan Barrett ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Alan and I are once again indebted to: The Pearse and Simon family for special access to Tamarisk Farm The Yeates family for special access to parts of their farm The Othona Community for special access to their grounds The Dorset Wildlife Trust The National Trust This report was complied with observations made by ourselves with contributions from: Ian McLean Graham Barrett Dave Foot Cliff Rogers Paul Harris Mike Hannam Adam Simon Neil Croton Simone Webber James McCarthy Gavin Haig Tony Warren Roger Hewitt Front Cover – Bearded Tit (West Bexington 2nd November 2015) Back Cover – Pomarine Skua (West Bexington 2nd June 2015) All images taken by Mike Morse unless credited otherwise 1 REVIEW OF THE YEAR January As was the case in 2014, the year started with a Great Skua on the 1st; a Jack Snipe was seen the following day. 3 Cirl Buntings were discovered on the 7th, but had likely been present from the beginning of the year, they were to stay all month. A ‘Greenland’ White- fronted Goose was found on the 9th; it was to be seen intermittently until the 16th. Another Jack Snipe was seen on the 19th and 20 Red-throated Divers were noted on the 22nd; the highest count of the year. A Short-eared Owl was also seen on the 22nd. February The 3 Cirl Buntings were still present on the 1st and remained all month. A Jack Snipe was seen again on the 3rd and a Slavonian Grebe on the 10th. -

Devon Hedges and Wildlife 1: General Description and Conservation Significance

Devon hedges and wildlife 1: general description and conservation significance Devon's hedges are of tremendous importance for wildlife (biodiversity). Indeed, they are the most common and widely distributed wildlife habitat in Devon, forming a dense web across all but the highest ground in the county. This section presents an overview of the wildlife of Devon's hedges, highlighting features of particular conservation significance. Other sections provide more information on the flowers and other wildlife of banks, margins and ditches, with one focusing on dormice and another on hedgerow trees. Nearly all hedges in Devon outside gardens and urban places consist largely of native shrubs and trees. As such they are recognised under English law as a Habitat of Principal Importance for the conservation of biodiversity (Section 41 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities (NERC) Act 2006). Shaded stone faced hedgebanks often have luxuriant growths of mosses and ferns and plants like navelwort General description (below). Photo ©Robert Wolton, Drawing ©Heather Harley Most of our hedges have a species-rich shrub layer (that is, they support five or more native woody species in a 30 metre length), and the majority are ancient, as is shown by often abundant displays of plants typical of ancient woodland such as bluebells, ransoms (wild garlic) and dog's mercury. Although ancient species-rich hedges usually support the greatest wildlife interest, even single species hedges are valuable. For example, redstarts breed in holes in the hedge beech trees of Exmoor and Dartmoor. The sides of banks are often covered with a luxuriant and diverse range of ferns and flowering plants, while the woody stems and toads and newts. -

Why Does Predator Abundance Increase After Invasion of a Non-Native Prey?

Why does predator abundance increase after invasion of a non-native prey? Erin O’Shaughnessey Advisor: Dr. Lauren Pintor 2 Abstract Invasive species have been shown to have substantial effects on native food webs though their potential roles as novel predators or novel prey. As novel prey, invasive species have been recently shown to cause native predator populations to increase in abundance and growth rate following introduction. However, we know little about whether the magnitude of the effect of invasive species as novel prey depends on particular traits of native predator species. The goal of this study was to conduct a literature search to identify the characteristics of native predators that might influence the magnitude of effect that non-native prey might have on predator abundance. Specifically, we recorded whether a predator was a generalist or specialist and then quantified the number of different prey types consumed by that native predator. In general, the lowest level of taxonomic resolution that could be obtained for most prey consumed by predators in the dataset was Order. We conducted a simple linear regression to look at whether the number of orders consumed by a predator explained variation in the magnitude of effect size that a non- native, prey species had on the predator’s abundance. Results suggest that there is no relationship between the number of taxonomic orders consumed by the predator and the estimated effect size of a non-native prey on the native predator. There is, however, a relationship between whether a predator is a carnivore or omnivore and their change in abundance. -

Emberiza Cirlus in the UK’, Oryx, , Pp

RVC OPEN ACCESS REPOSITORY – COPYRIGHT NOTICE This is the author’s accepted manuscript of the following article: Fountain, K., Jeffs, C., Croft, S., Gregson, J., Lister, J., Evans, A., Carter, I., Chang, Y.M. and Sainsbury, A.W. (2016) ‘The influence of risk factors associated with captive rearing on post-release survival in translocated cirl buntings Emberiza cirlus in the UK’, Oryx, , pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0030605315001313. The final publication is available at Cambridge Journals via https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605315001313. The full details of the published version of the article are as follows: TITLE: The influence of risk factors associated with captive rearing on post-release survival in translocated cirl buntings Emberiza cirlus in the UK AUTHORS: Fountain, K., Jeffs, C., Croft, S., Gregson, J., Lister, J., Evans, A., Carter, I., Chang, Y.M. and Sainsbury, A.W. JOURNAL TITLE: Oryx PUBLICATION DATE: 3 March 2016 (online) PUBLISHER: Cambridge University Press: STM Journals DOI: 10.1017/S0030605315001313 K. Fountain et al. Survival of translocated cirl buntings The influence of risk factors associated with captive rearing on post-release survival in translocated cirl buntings Emberiza cirlus in the UK K. Fountain, C. JEFFS, S. CROFT, J. GREGSON, J. LISTER, A. EVANS, I. CARTER, Y. M. CHANG and A. W. SAINSBURY K. FOUNTAIN (Corresponding author) and A. W. SAINSBURY Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY, UK. E-mail [email protected] C. JEFFS, S. CROFT and A. EVANS Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Sandy, Bedfordshire, UK J. GREGSON Paignton Zoo and Environmental Park, Paignton, Devon, UK J. -

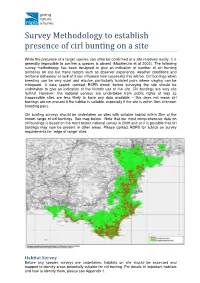

Survey Methodology to Establish Presence of Cirl Bunting on a Site

Survey Methodology to establish presence of cirl bunting on a site While the presence of a target species can often be confirmed at a site relatively easily, it is generally impossible to confirm a species is absent (MacKenzie et al 2002). The following survey methodology has been designed to give an indication of number of cirl bunting territories on site but many factors such as observer experience, weather conditions and territorial behaviour or lack of it can influence how successful this will be. Cirl buntings when breeding can be very quiet and elusive, particularly isolated pairs where singing can be infrequent. A data search (contact RSPB direct) before surveying the site should be undertaken to give an indication of the historic use of the site. Cirl buntings are very site faithful. However, the national surveys are undertaken from public rights of way so inaccessible sites are less likely to have any data available – this does not mean cirl buntings are not present if the habitat is suitable, especially if the site is within 2km of known breeding pairs. Cirl bunting surveys should be undertaken on sites with suitable habitat within 2km of the known range of cirl buntings. See map below. Note that our most comprehensive data on cirl buntings is based on the most recent national survey in 2009 and so it is possible that cirl buntings may now be present in other areas. Please contact RSPB for advice on survey requirements for `edge of range’ sites. Habitat Survey Before any species surveys are undertaken, habitats on site should be assessed and mapped to identify areas potentially suitable for cirl bunting.