DOCUMENT RESUME Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GE Targets Homegrown Talent in Hiring Blitz

20110829-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 8/26/2011 5:54 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 27, No. 36 AUGUST 29 – SEPTEMBER 4, 2011 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2011 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved Page 3 General fund won’t solve GE targets homegrown state’s UI debt troubles talent in hiring blitz BY DUSTIN WALSH When GE announced the $100 million expan- CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS sion at the Grace Lake Corporate Center site, for- merly Visteon Village, in 2009 with intentions General Electric Co.’s hiring spree in Southeast of hiring 1,100 workers averaging a $100,000 Michigan is anchored by local talent experi- salary, recruiters began looking to in-state enced in information technology. groups and programs to identify the area’s top About 90 percent of the center’s 700 employ- talent. Bankrupt jeweler’s legacy: ees at its Advanced Manufacturing and Soft- Tina Watson, an infrastructure manager at Two shops now aim to grow ware Technology Center in Van Buren Town- the center, interviewed for her position at GE ship hail from Michigan, said Kim Bankston, early last year and suggested the recruiter senior human resources leader for the site and check out the LinkedIn group she was running, corporate IT. Baker’s Dozen — which was an exclusive invi- The company is hiring about 10 IT profes- Inside JOHN SOBCZAK tation-only networking group of out-of-work IT “Incentives were how we’re able to put people sionals a week, and by 2013, the Van Buren fa- professionals founded by Gary Baker, now the In home stretch, RiverWalk here,” said Kim Bankston, senior human resources cility is expected to house the largest concen- leader for GE’s center in Van Buren Township. -

Der Spiegel-Confirmation from the East by Brian Crozier 1993

"Der Spiegel: Confirmation from the East" Counter Culture Contribution by Brian Crozier I WELCOME Sir James Goldsmith's offer of hospitality in the pages of COUNTER CULTURE to bring fresh news on a struggle in which we were both involved. On the attacking side was Herr Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the German news magazine, Der Spiegel; on the defending side was Jimmy. My own involvement was twofold: I provided him with the explosive information that drew fire from Augstein, and I co-ordinated a truly massive international research campaign that caused Augstein, nearly four years later, to call off his libel suit against Jimmy.1 History moves fast these days. The collapse of communism in the ex-Soviet Union and eastern Europe has loosened tongues and opened archives. The struggle I mentioned took place between January 1981 and October 1984. The past two years have brought revelations and confessions that further vindicate the line we took a decade ago. What did Jimmy Goldsmith say, in 1981, that roused Augstein to take legal action? The Media Committee of the House of Commons had invited Sir James to deliver an address on 'Subversion in the Media'. Having read a reference to the 'Spiegel affair' of 1962 in an interview with the late Franz Josef Strauss in his own news magazine of that period, NOW!, he wanted to know more. I was the interviewer. Today's readers, even in Germany, may not automatically react to the sight or sound of the' Spiegel affair', but in its day, this was a major political scandal, which seriously damaged the political career of Franz Josef Strauss, the then West German Defence Minister. -

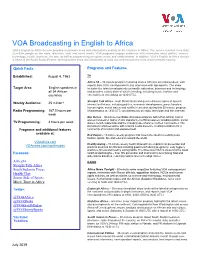

VOA E2A Fact Sheet

VOA Broadcasting in English to Africa VOA’s English to Africa Service provides multimedia news and information covering all 54 countries in Africa. The service reaches more than 25 million people on the radio, television, web, and social media. VOA programs engage audiences with information about politics, science, technology, health, business, the arts, as well as programming on sports, music and entertainment. In addition, VOA’s English to Africa service is home to the South Sudan Project, which provides news and information to radio and web consumers in the world’s newest country. Quick Facts Programs and Features Established: August 4, 1963 TV Africa 54 – 30-minute program featuring stories Africans are talking about, with reports from VOA correspondents and interviews with top experts. The show Target Area: English speakers in includes the latest developments on health, education, business and technology, all 54 African and provides a daily dose of what’s trending, including music, fashion and countries entertainment (weekdays at 1630 UTC). Straight Talk Africa - Host Shaka Ssali and guests discuss topics of special Weekly Audience: 25 million+ interest to Africans, including politics, economic development, press freedom, human rights, social issues and conflict resolution during this 60-minute program. Radio Programming: 167.5 hours per (Wednesdays at 1830 UTC simultaneously on radio, television and the Internet). week Our Voices – 30-minute roundtable discussion program with a Pan-African cast of women focused on topics of vital importance to African women including politics, social TV Programming: 4 hours per week issues, health, leadership and the changing role of women in their communities. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

CBS News Archives, Our Efforts in Preservation and End with Some Suggestions Addressing the Mission of This Panel

DOUG MCKINNEY, DIRECTOR, CBS-NEWS ARCHIVES FOR ORAL PRESENTATION TO LIBRARY OF CONGRESS STUDY RE TV . PRESERVATION (3/19/96): It is with a combination of some relief and awe that we come before this panel, the nature of which has been imagined as a hoped-for eventuality, now gladly arrived. While many eloquent voices are here to cry, we no longer face such a wilderness. The preservation of entertainment programming as it applies to CBS will be addressed by other counterparts at the Los Angeles hearing. Today, in tandem with Mr. DeCesare, I will focus my remarks on the nature of CBS News Archives, our efforts in preservation and end with some suggestions addressing the mission of this panel. CBS has the largest collection of its kind among the major networks, having kept and maintained more material generally in addition to having started earlier. Dating principally from 1950 to the present, CBS News Archives has well over a million videotapes, including original field cassettes as well as program broadcasts, and several million feet of hard news film, as well as 80,000 containers of film and tape masters, . prints, program negatives and outtake material from long-form documentaries and news magazine programs. All materials are stored in Manhattan on approximabely 60,000 square feet of climate-controlled space. (All nitrate film was transferred to safety stock some years ago.) In addition,. copies of the CBS Evening News from the mid-'70s to present, and of many other CBS News broadcasts including special and documentary programs are on deposit at the National Archives via Library of Congress copyright registration. -

In Between Spectacle and Political Correctness: Vamos Con Todo – an Ambivalent News/Talk Show1

Pragmatics 23:1.117-145 (2013) International Pragmatics Association DOI: 10.1075/prag.23.1.06pla IN BETWEEN SPECTACLE AND POLITICAL CORRECTNESS: VAMOS CON TODO – AN AMBIVALENT NEWS/TALK SHOW1 María Elena Placencia and Catalina Fuentes Rodríguez Abstract Vamos con todo is a mixed-genre entertainment programme transmitted in Ecuador on a national television channel. The segment of the programme that we examine in this paper focuses on gossip and events surrounding local/national celebrities. Talk as entertainment is central to this segment which is structured around a series of ‘news’ stories announced by the presenters and mostly conveyed through (pre-recorded) interviews. Extracts of these interviews are ingeniously presented to create a sense of confrontation between the celebrities concerned. Each news story is then followed-up by informal ‘discussions’ among the show’s 5-6 presenters who take on the role of panellists. While Vamos con todo incorporates various genres, the running thread throughout the programme is the creation of scandal and the instigation of confrontation. What is of particular interest, however, is that no sooner the scandalous stories are presented, the programme presenters attempt to defuse the scandal and controversy that they contributed to creating. The programme thus results in what viewers familiar with the genre of confrontational talk shows in Spain, for example, may regard as an emasculated equivalent. In this paper we explore linguistic and other mechanisms through which confrontation and scandal are first created and then defused in Vamos con todo. We consider the situational, cultural and socio-political context of the programme as possibly playing a part in this disjointedness. -

Gender-Based Use of Negative Concord in Non- Standard American English

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Gender-Based Use of Negative Concord in Non- Standard American English Henriikka Malkamäki Pro Gradu Thesis English Philology Department of Modern Languages University of Helsinki October 2013 2 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Nykykielten laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Henriikka Malkamäki Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Kaksoisnegaatio miesten ja naisten puhumassa amerikanenglannissa Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Englantilainen filologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro Gradu -tutkielma Lokakuu 2013 68 + 4 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tämä työ tarkastelee kaksoisnegaatiota miesten ja naisten puhumassa amerikanenglannissa. Tutkimus toteutettiin vertaamalla kolmea eri negaatiomuotoparia. Tutkittuihin negaatiomuotoihin lukeutuivat standardikieliopista poikkeavat tuplanegaatiomuodot n’t nothing, not nothing ja never nothing, ja niiden vastaavat standardikieliopin mukaiset negaatiomuodot n’t anything, not anything ja never anything. Kyseisiä negaatiomuotoja haettiin Corpus of Contemporary American English -nimisessä korpuksessa olevasta puhutun kielen osiosta, ’spoken section’, joka koostuu litteroiduista TV- ja radio-ohjelmista. Tutkimuksen aineisto muodostui litteroitujen ohjelmien tekstiotteista, joissa negaatiomuodot ilmenivät. Sekä standardikieliopista poikkeavien muotojen käyttöaste että kieliopin mukaisesti rakennettujen muotojen käyttöaste (%) laskettiin -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Philip Matthew Stinson, Sr. 232

CURRICULUM VITAE PHILIP MATTHEW STINSON, SR. 232 Health & Human Services Building Criminal Justice Program Department of Human Services College of Health & Human Services Bowling Green State University Bowling Green, Ohio 43403-0147 419-372-0373 [email protected] I. Academic Degrees Ph.D., 2009 Department of Criminology College of Health & Human Services Indiana University of Pennsylvania Indiana, PA Dissertation Title: Police Crime: A Newsmaking Criminology Study of Sworn Law Enforcement Officers Arrested, 2005-2007 Dissertation Chair: Daniel Lee, Ph.D. M.S., 2005 Department of Criminal Justice College of Business and Public Affairs West Chester University of Pennsylvania West Chester, PA Thesis Title: Determining the Prevalence of Mental Health Needs in the Juvenile Justice System at Intake: A MAYSI-2 Comparison of Non- Detained and Detained Youth Thesis Chair: Brian F. O'Neill, Ph.D. J.D., 1992 David A. Clarke School of Law University of the District of Columbia Washington, DC B.S., 1986 Department of Public & International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences George Mason University Fairfax, VA A.A.S., 1984 Administration of Justice Program Northern Virginia Community College Annandale, VA 1 II. Academic Positions Professor, 2019-present (tenured) Associate Professor, 2015-2019 (tenured) Assistant Professor, 2009-2015 (tenure track) Criminal Justice Program, Department of Human Services Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH Assistant Professor, 2008-2009 (non-tenure track) Department of Criminology Indiana University of -

The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: a Corporate Profile

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Articles and Chapters ILR Collection 1-28-2004 The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Maria C. Figueroa Cornell University, [email protected] Damone Richardson Cornell University, [email protected] Pam Whitefield Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Arts Management Commons, and the Unions Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Abstract [Excerpt] This research was commissioned by the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) with the expressed purpose of assisting the organization and its affiliate unions – which represent some 500,000 media and related workers – in understanding, more fully, the changes taking place in the arts and entertainment industry. Specifically, this report examines the impact that Clear Channel Communications, with its dominant positions in radio, live entertainment and outdoor advertising, has had on the industry in general, and workers in particular. Keywords AFL-CIO, media, worker, arts, entertainment industry, advertising, organization, union, marketplace, deregulation, federal regulators Disciplines Advertising and Promotion Management | Arts Management | Unions Comments Suggested Citation Figueroa, M. -

Media Studies

Summer School Media Studies A Level Media Students Guide A media student should have an interest in the products around them, from film to TV, video games to radio. A media student needs to be able to look at the products they consume and ask why? Why has it been made? Why has some one made this product? Why have the representations been created in that specific way? Students will often go off to study media further specialising in film, TV, business or advertisement. The Take Yotube BBC Arts, Culture and the Media Programmes Film Riot Youtube Channel 4 News & Current Affairs Feminist Frequency YouTube TED Talks Film Theorists YouTube PechaKucha 20x20 Game Theorists YouTube Cinema Sins YouTube Easy Photo Class YouTube BBC Radio 1's Screen time Podcast BBC Radio 4’s Front Row BBC Radio 1’s Movie Mixtape BBFC Podcast Media Studies Media BBC Radio 5’s Must Watch Podcast Media Masters Podcast BBC Radio 5 Kermode & Mayo Film Reviews The BBC Academy Podcast BBC Radio 4’s The Media Show Media Voices Mobile Journalism Show The Guardian IGN BFI Film Academy Den of Geek Screenskills @HoEMedia on Twitter WhatCulture Creativebloq The Student Room Adobe Photoshop Tutorials Universal Extras - be an extra! Shooting People - Jobs in Films If you would like to share what you’ve learnt, we’d love for you to produce a piece of media that we could share with other students. Introduction To: Media Studies An introduction to Media Studies and the basic skills you will need Introduction Hello and welcome to Media Studies.