KLF4 Recruits SWI/SNF to Increase Chromatin Accessibility and Reprogram the Endothelial Enhancer Landscape Under Laminar Shear Stress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microglia Emerge from Erythromyeloid Precursors Via Pu.1- and Irf8-Dependent Pathways

ART ic LE S Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1- and Irf8-dependent pathways Katrin Kierdorf1,2, Daniel Erny1, Tobias Goldmann1, Victor Sander1, Christian Schulz3,4, Elisa Gomez Perdiguero3,4, Peter Wieghofer1,2, Annette Heinrich5, Pia Riemke6, Christoph Hölscher7,8, Dominik N Müller9, Bruno Luckow10, Thomas Brocker11, Katharina Debowski12, Günter Fritz1, Ghislain Opdenakker13, Andreas Diefenbach14, Knut Biber5,15, Mathias Heikenwalder16, Frederic Geissmann3,4, Frank Rosenbauer6 & Marco Prinz1,17 Microglia are crucial for immune responses in the brain. Although their origin from the yolk sac has been recognized for some time, their precise precursors and the transcription program that is used are not known. We found that mouse microglia were derived from primitive c-kit+ erythromyeloid precursors that were detected in the yolk sac as early as 8 d post conception. + lo − + − + These precursors developed into CD45 c-kit CX3CR1 immature (A1) cells and matured into CD45 c-kit CX3CR1 (A2) cells, as evidenced by the downregulation of CD31 and concomitant upregulation of F4/80 and macrophage colony stimulating factor receptor (MCSF-R). Proliferating A2 cells became microglia and invaded the developing brain using specific matrix metalloproteinases. Notably, microgliogenesis was not only dependent on the transcription factor Pu.1 (also known as Sfpi), but also required Irf8, which was vital for the development of the A2 population, whereas Myb, Id2, Batf3 and Klf4 were not required. Our data provide cellular and molecular insights into the origin and development of microglia. Microglia are the tissue macrophages of the brain and scavenge dying have the ability to give rise to microglia and macrophages in vitro cells, pathogens and molecules using pattern recognition receptors and in vivo under defined conditions. -

Interplay Between Epigenetics and Metabolism in Oncogenesis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches

OPEN Oncogene (2017) 36, 3359–3374 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW Interplay between epigenetics and metabolism in oncogenesis: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches CC Wong1, Y Qian2,3 and J Yu1 Epigenetic and metabolic alterations in cancer cells are highly intertwined. Oncogene-driven metabolic rewiring modifies the epigenetic landscape via modulating the activities of DNA and histone modification enzymes at the metabolite level. Conversely, epigenetic mechanisms regulate the expression of metabolic genes, thereby altering the metabolome. Epigenetic-metabolomic interplay has a critical role in tumourigenesis by coordinately sustaining cell proliferation, metastasis and pluripotency. Understanding the link between epigenetics and metabolism could unravel novel molecular targets, whose intervention may lead to improvements in cancer treatment. In this review, we summarized the recent discoveries linking epigenetics and metabolism and their underlying roles in tumorigenesis; and highlighted the promising molecular targets, with an update on the development of small molecule or biologic inhibitors against these abnormalities in cancer. Oncogene (2017) 36, 3359–3374; doi:10.1038/onc.2016.485; published online 16 January 2017 INTRODUCTION metabolic genes have also been identified as driver genes It has been appreciated since the early days of cancer research mutated in some cancers, such as isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 16 17 that the metabolic profiles of tumor cells differ significantly from and 2 (IDH1/2) in gliomas and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 18 normal cells. Cancer cells have high metabolic demands and they succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in paragangliomas and fuma- utilize nutrients with an altered metabolic program to support rate hydratase (FH) in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell 19 their high proliferative rates and adapt to the hostile tumor cancer (HLRCC). -

Mutant IDH, (R)-2-Hydroxyglutarate, and Cancer

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 1, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW What a difference a hydroxyl makes: mutant IDH, (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate, and cancer Julie-Aurore Losman1 and William G. Kaelin Jr.1,2,3 1Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA; 2Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815, USA Mutations in metabolic enzymes, including isocitrate whether altered cellular metabolism is a cause of cancer dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and IDH2, in cancer strongly or merely an adaptive response of cancer cells in the face implicate altered metabolism in tumorigenesis. IDH1 of accelerated cell proliferation is still a topic of some and IDH2 catalyze the interconversion of isocitrate and debate. 2-oxoglutarate (2OG). 2OG is a TCA cycle intermediate The recent identification of cancer-associated muta- and an essential cofactor for many enzymes, including tions in three metabolic enzymes suggests that altered JmjC domain-containing histone demethylases, TET cellular metabolism can indeed be a cause of some 5-methylcytosine hydroxylases, and EglN prolyl-4-hydrox- cancers (Pollard et al. 2003; King et al. 2006; Raimundo ylases. Cancer-associated IDH mutations alter the enzymes et al. 2011). Two of these enzymes, fumarate hydratase such that they reduce 2OG to the structurally similar (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), are bone fide metabolite (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate [(R)-2HG]. Here we tumor suppressors, and loss-of-function mutations in FH review what is known about the molecular mechanisms and SDH have been identified in various cancers, in- of transformation by mutant IDH and discuss their im- cluding renal cell carcinomas and paragangliomas. -

ERG Dependence Distinguishes Developmental Control of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Maintenance from Hematopoietic Specification

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 28, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press ERG dependence distinguishes developmental control of hematopoietic stem cell maintenance from hematopoietic specification Samir Taoudi,1,2,6 Thomas Bee,3 Adrienne Hilton,1 Kathy Knezevic,3 Julie Scott,4 Tracy A. Willson,1,2 Caitlin Collin,1 Tim Thomas,1,2 Anne K. Voss,1,2 Benjamin T. Kile,1,2 Warren S. Alexander,2,5 John E. Pimanda,3 and Douglas J. Hilton1,2 1Molecular Medicine Division, The Walter and Eliza Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; 2Department of Medical Biology, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3010, Australia; 3Lowy Cancer Research Centre, The Prince of Wales Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, Australia; 4Microinjection Services, The Walter and Eliza Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; 5Cancer and Haematology Division, The Walter and Eliza Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia Although many genes are known to be critical for early hematopoiesis in the embryo, it remains unclear whether distinct regulatory pathways exist to control hematopoietic specification versus hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) emergence and function. Due to their interaction with key regulators of hematopoietic commitment, particular interest has focused on the role of the ETS family of transcription factors; of these, ERG is predicted to play an important role in the initiation of hematopoiesis, yet we do not know if or when ERG is required. Using in vitro and in vivo models of hematopoiesis and HSC development, we provide strong evidence that ERG is at the center of a distinct regulatory program that is not required for hematopoietic specification or differentiation but is critical for HSC maintenance during embryonic development. -

Ubiquitin-Mediated Control of ETS Transcription Factors: Roles in Cancer and Development

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Ubiquitin-Mediated Control of ETS Transcription Factors: Roles in Cancer and Development Charles Ducker * and Peter E. Shaw * Queen’s Medical Centre, School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2UH, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.D.); [email protected] (P.E.S.) Abstract: Genome expansion, whole genome and gene duplication events during metazoan evolution produced an extensive family of ETS genes whose members express transcription factors with a conserved winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain. Unravelling their biological roles has proved challenging with functional redundancy manifest in overlapping expression patterns, a common consensus DNA-binding motif and responsiveness to mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling. Key determinants of the cellular repertoire of ETS proteins are their stability and turnover, controlled largely by the actions of selective E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases. Here we discuss the known relationships between ETS proteins and enzymes that determine their ubiquitin status, their integration with other developmental signal transduction pathways and how suppression of ETS protein ubiquitination contributes to the malignant cell phenotype in multiple cancers. Keywords: E3 ligase complex; deubiquitinase; gene fusions; mitogens; phosphorylation; DNA damage 1. Introduction Citation: Ducker, C.; Shaw, P.E. Cell growth, proliferation and differentiation are complex, concerted processes that Ubiquitin-Mediated Control of ETS Transcription Factors: Roles in Cancer rely on careful regulation of gene expression. Control over gene expression is maintained and Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. through signalling pathways that respond to external cellular stimuli, such as growth 2021, 22, 5119. https://doi.org/ factors, cytokines and chemokines, that invoke expression profiles commensurate with 10.3390/ijms22105119 diverse cellular outcomes. -

Inducible Transgene Expression in PDX Models

Liu et al. Biomarker Research (2020) 8:46 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00226-z RESEARCH Open Access Inducible transgene expression in PDX models in vivo identifies KLF4 as a therapeutic target for B-ALL Wen-Hsin Liu1, Paulina Mrozek-Gorska2, Anna-Katharina Wirth1, Tobias Herold1,3, Larissa Schwarzkopf1, Dagmar Pich2, Kerstin Völse1, M. Camila Melo-Narváez2, Michela Carlet1, Wolfgang Hammerschmidt2,4 and Irmela Jeremias1,5,6* Abstract Background: Clinically relevant methods are not available that prioritize and validate potential therapeutic targets for individual tumors, from the vast amount of tumor descriptive expression data. Methods: We established inducible transgene expression in clinically relevant patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models in vivo to fill this gap. Results: With this technique at hand, we analyzed the role of the transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) PDX models at different disease stages. In competitive preclinical in vivo trials, we found that re-expression of wild type KLF4 reduced the leukemia load in PDX models of B-ALL, with the strongest effects being observed after conventional chemotherapy in minimal residual disease (MRD). A nonfunctional KLF4 mutant had no effect on this model. The re-expression of KLF4 sensitized tumor cells in the PDX model towards systemic chemotherapy in vivo. It is of major translational relevance that azacitidine upregulated KLF4 levels in the PDX model and a KLF4 knockout reduced azacitidine-induced cell death, suggesting that azacitidine can regulate KLF4 re-expression. These results support the application of azacitidine in patients with B-ALL as a therapeutic option to regulate KLF4. -

Ten Commandments for a Good Scientist

Unravelling the mechanism of differential biological responses induced by food-borne xeno- and phyto-estrogenic compounds Ana María Sotoca Covaleda Wageningen 2010 Thesis committee Thesis supervisors Prof. dr. ir. Ivonne M.C.M. Rietjens Professor of Toxicology Wageningen University Prof. dr. Albertinka J. Murk Personal chair at the sub-department of Toxicology Wageningen University Thesis co-supervisor Dr. ir. Jacques J.M. Vervoort Associate professor at the Laboratory of Biochemistry Wageningen University Other members Prof. dr. Michael R. Muller, Wageningen University Prof. dr. ir. Huub F.J. Savelkoul, Wageningen University Prof. dr. Everardus J. van Zoelen, Radboud University Nijmegen Dr. ir. Toine F.H. Bovee, RIKILT, Wageningen This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School VLAG Unravelling the mechanism of differential biological responses induced by food-borne xeno- and phyto-estrogenic compounds Ana María Sotoca Covaleda Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Tuesday 14 September 2010 at 4 p.m. in the Aula Unravelling the mechanism of differential biological responses induced by food-borne xeno- and phyto-estrogenic compounds. Ana María Sotoca Covaleda Thesis Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010, With references, and with summary in Dutch. ISBN: 978-90-8585-707-5 “Caminante no hay camino, se hace camino al andar. Al andar se hace camino, y al volver la vista atrás se ve la senda que nunca se ha de volver a pisar” - Antonio Machado – A mi madre. -

1714 Gene Comprehensive Cancer Panel Enriched for Clinically Actionable Genes with Additional Biologically Relevant Genes 400-500X Average Coverage on Tumor

xO GENE PANEL 1714 gene comprehensive cancer panel enriched for clinically actionable genes with additional biologically relevant genes 400-500x average coverage on tumor Genes A-C Genes D-F Genes G-I Genes J-L AATK ATAD2B BTG1 CDH7 CREM DACH1 EPHA1 FES G6PC3 HGF IL18RAP JADE1 LMO1 ABCA1 ATF1 BTG2 CDK1 CRHR1 DACH2 EPHA2 FEV G6PD HIF1A IL1R1 JAK1 LMO2 ABCB1 ATM BTG3 CDK10 CRK DAXX EPHA3 FGF1 GAB1 HIF1AN IL1R2 JAK2 LMO7 ABCB11 ATR BTK CDK11A CRKL DBH EPHA4 FGF10 GAB2 HIST1H1E IL1RAP JAK3 LMTK2 ABCB4 ATRX BTRC CDK11B CRLF2 DCC EPHA5 FGF11 GABPA HIST1H3B IL20RA JARID2 LMTK3 ABCC1 AURKA BUB1 CDK12 CRTC1 DCUN1D1 EPHA6 FGF12 GALNT12 HIST1H4E IL20RB JAZF1 LPHN2 ABCC2 AURKB BUB1B CDK13 CRTC2 DCUN1D2 EPHA7 FGF13 GATA1 HLA-A IL21R JMJD1C LPHN3 ABCG1 AURKC BUB3 CDK14 CRTC3 DDB2 EPHA8 FGF14 GATA2 HLA-B IL22RA1 JMJD4 LPP ABCG2 AXIN1 C11orf30 CDK15 CSF1 DDIT3 EPHB1 FGF16 GATA3 HLF IL22RA2 JMJD6 LRP1B ABI1 AXIN2 CACNA1C CDK16 CSF1R DDR1 EPHB2 FGF17 GATA5 HLTF IL23R JMJD7 LRP5 ABL1 AXL CACNA1S CDK17 CSF2RA DDR2 EPHB3 FGF18 GATA6 HMGA1 IL2RA JMJD8 LRP6 ABL2 B2M CACNB2 CDK18 CSF2RB DDX3X EPHB4 FGF19 GDNF HMGA2 IL2RB JUN LRRK2 ACE BABAM1 CADM2 CDK19 CSF3R DDX5 EPHB6 FGF2 GFI1 HMGCR IL2RG JUNB LSM1 ACSL6 BACH1 CALR CDK2 CSK DDX6 EPOR FGF20 GFI1B HNF1A IL3 JUND LTK ACTA2 BACH2 CAMTA1 CDK20 CSNK1D DEK ERBB2 FGF21 GFRA4 HNF1B IL3RA JUP LYL1 ACTC1 BAG4 CAPRIN2 CDK3 CSNK1E DHFR ERBB3 FGF22 GGCX HNRNPA3 IL4R KAT2A LYN ACVR1 BAI3 CARD10 CDK4 CTCF DHH ERBB4 FGF23 GHR HOXA10 IL5RA KAT2B LZTR1 ACVR1B BAP1 CARD11 CDK5 CTCFL DIAPH1 ERCC1 FGF3 GID4 HOXA11 IL6R KAT5 ACVR2A -

A Dual Cis-Regulatory Code Links IRF8 to Constitutive and Inducible Gene Expression in Macrophages

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 1, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press A dual cis-regulatory code links IRF8 to constitutive and inducible gene expression in macrophages Alessandra Mancino,1,3 Alberto Termanini,1,3 Iros Barozzi,1 Serena Ghisletti,1 Renato Ostuni,1 Elena Prosperini,1 Keiko Ozato,2 and Gioacchino Natoli1 1Department of Experimental Oncology, European Institute of Oncology (IEO), 20139 Milan, Italy; 2Laboratory of Molecular Growth Regulation, Genomics of Differentiation Program, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA The transcription factor (TF) interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8) controls both developmental and inflammatory stimulus-inducible genes in macrophages, but the mechanisms underlying these two different functions are largely unknown. One possibility is that these different roles are linked to the ability of IRF8 to bind alternative DNA sequences. We found that IRF8 is recruited to distinct sets of DNA consensus sequences before and after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. In resting cells, IRF8 was mainly bound to composite sites together with the master regulator of myeloid development PU.1. Basal IRF8–PU.1 binding maintained the expression of a broad panel of genes essential for macrophage functions (such as microbial recognition and response to purines) and contributed to basal expression of many LPS-inducible genes. After LPS stimulation, increased expression of IRF8, other IRFs, and AP-1 family TFs enabled IRF8 binding to thousands of additional regions containing low-affinity multimerized IRF sites and composite IRF–AP-1 sites, which were not premarked by PU.1 and did not contribute to the basal IRF8 cistrome. -

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Metallomics

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Metallomics. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2018 Uniprot Entry name Gene names Protein names Predicted Pattern Number of Iron role EC number Subcellular Membrane Involvement in disease Gene ontology (biological process) Id iron ions location associated 1 P46952 3HAO_HUMAN HAAO 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4- H47-E53-H91 1 Fe cation Catalytic 1.13.11.6 Cytoplasm No NAD biosynthetic process [GO:0009435]; neuron cellular homeostasis dioxygenase (EC 1.13.11.6) (3- [GO:0070050]; quinolinate biosynthetic process [GO:0019805]; response to hydroxyanthranilate oxygenase) cadmium ion [GO:0046686]; response to zinc ion [GO:0010043]; tryptophan (3-HAO) (3-hydroxyanthranilic catabolic process [GO:0006569] acid dioxygenase) (HAD) 2 O00767 ACOD_HUMAN SCD Acyl-CoA desaturase (EC H120-H125-H157-H161; 2 Fe cations Catalytic 1.14.19.1 Endoplasmic Yes long-chain fatty-acyl-CoA biosynthetic process [GO:0035338]; unsaturated fatty 1.14.19.1) (Delta(9)-desaturase) H160-H269-H298-H302 reticulum acid biosynthetic process [GO:0006636] (Delta-9 desaturase) (Fatty acid desaturase) (Stearoyl-CoA desaturase) (hSCD1) 3 Q6ZNF0 ACP7_HUMAN ACP7 PAPL PAPL1 Acid phosphatase type 7 (EC D141-D170-Y173-H335 1 Fe cation Catalytic 3.1.3.2 Extracellular No 3.1.3.2) (Purple acid space phosphatase long form) 4 Q96SZ5 AEDO_HUMAN ADO C10orf22 2-aminoethanethiol dioxygenase H112-H114-H193 1 Fe cation Catalytic 1.13.11.19 Unknown No oxidation-reduction process [GO:0055114]; sulfur amino acid catabolic process (EC 1.13.11.19) (Cysteamine -

Genequery™ Human Stem Cell Transcription Factors Qpcr Array

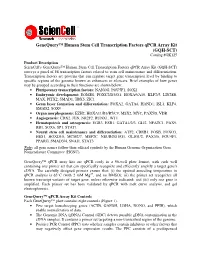

GeneQuery™ Human Stem Cell Transcription Factors qPCR Array Kit (GQH-SCT) Catalog #GK125 Product Description ScienCell's GeneQuery™ Human Stem Cell Transcription Factors qPCR Array Kit (GQH-SCT) surveys a panel of 88 transcription factors related to stem cell maintenance and differentiation. Transcription factors are proteins that can regulate target gene transcription level by binding to specific regions of the genome known as enhancers or silencers. Brief examples of how genes may be grouped according to their functions are shown below: • Pluripotency transcription factors: NANOG, POU5F1, SOX2 • Embryonic development: EOMES, FOXC2/D3/O1, HOXA9/A10, KLF2/5, LIN28B, MAX, PITX2, SMAD1, TBX5, ZIC1 • Germ layer formation and differentiation: FOXA2, GATA6, HAND1, ISL1, KLF4, SMAD2, SOX9 • Organ morphogenesis: EZH2, HOXA11/B3/B5/C9, MSX2, MYC, PAX5/8, VDR • Angiogenesis: CDX2, JUN, NR2F2, RUNX1, WT1 • Hematopoiesis and osteogenesis: EGR3, ESR1, GATA1/2/3, GLI2, NFATC1, PAX9, RB1, SOX6, SP1, STAT1 • Neural stem cell maintenance and differentiation: ATF2, CREB1, FOSB, FOXO3, HES1, HOXD10, MCM2/7, MEF2C, NEUROD1/G1, OLIG1/2, PAX3/6, POU4F1, PPARG, SMAD3/4, SNAI1, STAT3 Note : all gene names follow their official symbols by the Human Genome Organization Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC). GeneQuery™ qPCR array kits are qPCR ready in a 96-well plate format, with each well containing one primer set that can specifically recognize and efficiently amplify a target gene's cDNA. The carefully designed primers ensure that: (i) the optimal annealing temperature in qPCR analysis is 65°C (with 2 mM Mg 2+ , and no DMSO); (ii) the primer set recognizes all known transcript variants of target gene, unless otherwise indicated; and (iii) only one gene is amplified. -

Xo GENE PANEL

xO GENE PANEL Targeted panel of 1714 genes | Tumor DNA Coverage: 500x | RNA reads: 50 million Onco-seq panel includes clinically relevant genes and a wide array of biologically relevant genes Genes A-C Genes D-F Genes G-I Genes J-L AATK ATAD2B BTG1 CDH7 CREM DACH1 EPHA1 FES G6PC3 HGF IL18RAP JADE1 LMO1 ABCA1 ATF1 BTG2 CDK1 CRHR1 DACH2 EPHA2 FEV G6PD HIF1A IL1R1 JAK1 LMO2 ABCB1 ATM BTG3 CDK10 CRK DAXX EPHA3 FGF1 GAB1 HIF1AN IL1R2 JAK2 LMO7 ABCB11 ATR BTK CDK11A CRKL DBH EPHA4 FGF10 GAB2 HIST1H1E IL1RAP JAK3 LMTK2 ABCB4 ATRX BTRC CDK11B CRLF2 DCC EPHA5 FGF11 GABPA HIST1H3B IL20RA JARID2 LMTK3 ABCC1 AURKA BUB1 CDK12 CRTC1 DCUN1D1 EPHA6 FGF12 GALNT12 HIST1H4E IL20RB JAZF1 LPHN2 ABCC2 AURKB BUB1B CDK13 CRTC2 DCUN1D2 EPHA7 FGF13 GATA1 HLA-A IL21R JMJD1C LPHN3 ABCG1 AURKC BUB3 CDK14 CRTC3 DDB2 EPHA8 FGF14 GATA2 HLA-B IL22RA1 JMJD4 LPP ABCG2 AXIN1 C11orf30 CDK15 CSF1 DDIT3 EPHB1 FGF16 GATA3 HLF IL22RA2 JMJD6 LRP1B ABI1 AXIN2 CACNA1C CDK16 CSF1R DDR1 EPHB2 FGF17 GATA5 HLTF IL23R JMJD7 LRP5 ABL1 AXL CACNA1S CDK17 CSF2RA DDR2 EPHB3 FGF18 GATA6 HMGA1 IL2RA JMJD8 LRP6 ABL2 B2M CACNB2 CDK18 CSF2RB DDX3X EPHB4 FGF19 GDNF HMGA2 IL2RB JUN LRRK2 ACE BABAM1 CADM2 CDK19 CSF3R DDX5 EPHB6 FGF2 GFI1 HMGCR IL2RG JUNB LSM1 ACSL6 BACH1 CALR CDK2 CSK DDX6 EPOR FGF20 GFI1B HNF1A IL3 JUND LTK ACTA2 BACH2 CAMTA1 CDK20 CSNK1D DEK ERBB2 FGF21 GFRA4 HNF1B IL3RA JUP LYL1 ACTC1 BAG4 CAPRIN2 CDK3 CSNK1E DHFR ERBB3 FGF22 GGCX HNRNPA3 IL4R KAT2A LYN ACVR1 BAI3 CARD10 CDK4 CTCF DHH ERBB4 FGF23 GHR HOXA10 IL5RA KAT2B LZTR1 ACVR1B BAP1 CARD11 CDK5 CTCFL DIAPH1 ERCC1 FGF3 GID4