Contemporary Cruise Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Century at Sea Jul

Guernsey's A Century at Sea (Day 1) Newport, RI Friday - July 19, 2019 A Century at Sea (Day 1) Newport, RI 1: NS Savannah Set of China (31 pieces) USD 800 - 1,200 A collection of thirty-one (31) pieces of china from the NS Savannah. This set of china includes the following pieces: two (2) 10" round plates, three (3) 9 1/2" round plates, one (1) 10" novelty plate, one (1) 9 1/4" x 7" oval plate, one (1) 7 1/4" round plate, four (4) 6" round plates, one (1) ceramic drinking pitcher, one (1) cappachino cup and saucer (diameter of 4 1/2"), two (2) coffee cups and saucers (diameter 4"), one (1) 3 1/2" round cup, one (1) 3" x 3" round cup, one (1) 2 1/2" x 3" drinking glass, one (1) mini cognac glass, two (2) 2" x 4 1/2" shot glasses, three (3) drinking glasses, one (1) 3" x 5" wine glass, two (2) 4 1/2" x 8 3/4" silver dishes. The ship was remarkable in that it was the first nuclear-powered merchant ship. It was constructed with funding from United States government agencies with the mission to prove that the US was committed to the proposition of using atomic power for peace and part of President Eisenhower's larger "Atoms for Peace" project. The sleek and modern design of the ship led to some maritime historians believing it was the prettiest merchant ship ever built. This china embodies both the mission of using nuclear power for peace while incorporating the design inclinations of the ship. -

ZEEBRIEF#173 12 December 2020

ZEEBRIEF#173 12 december 2020 Fijne Kerstdagen Een Goed & Gezond 2021 NIEUWSBRIEF 275 ALEXIA, IMO 9369083 (NB-216), Damen Combi Freighter 11000, 23-8-2005 contract, 13-1-2007 kiel gelegd bij Yichang Damen Shipyards Co. Ltd. (567303), 8-10-2007 te water, 3-1-2008 opgeleverd als ALEXIA door Damen Shipyards B.V. (567303) aan M.S. “Jolina” Schiffahrts G.m.b.H. & Co. Reederei K.G., Antigua & Barbuda, roepsein V2DE5, in beheer bij Intersee Schiffahrts G.m.b.H. & Co., Haren/Ems en Damen Shipyards B.V. 14-4-2008 (e) onder de vlag van de Ned. Antillen gebracht, thuishaven: Willemstad- N.A., roepsein PJSX, in beheer bij Transship B.V., Emmen voor Intersee Schiffahrts G.m.b.H. & Co., Haren/Ems. 7.878 GT. 10-10-2010 vlag: Curaçao. 10-5-2015 ETA vanaf Reydarfjordur voor Steinweg in de Frisohaven te Rotterdam. 12-5-2015 verkocht aan Marmactan Schiffahrts G.m.b.H. & Co. K.G, 5-2015 onder de vlag van Antigua & Barbuda gebracht, thuishaven: St. John's, roepsein V2GS5, in beheer bij MarConsult Schiffahrt (G.m.b.H. & Co.) K.G, Hamburg, 5-2015 herdoopt MARMACTAN. 12-5-2015 verhaald van de Frisohaven te Rotterdam naar de Hartelhaven in de Europoort onder de nieuwe naam. 13- 5-2015 van de Europoort naar Høgset, Noorwegen, 15-5-2015 ETA te Høgset. 12-11-2020 (GL) verkocht ARA Bergen Shipping B.V., Portugal (Madeira), roepsein CQEH2, in beheer bij ARA Ship Management B.V., herdoopt UNISTORM. (Foto: Henk Jungerius, 4-2-2020). ALSERBACH, IMO 9169732 (NB-213), 21-9-1997 te water gelaten bij Shipbuilding Yard Slip Joint Stock Co., Rybinsk (61604), 12-1997 opgeleverd door Peters-Werft Wewelsfleth G.m.b.H. -

"Corporation Stricted Speculation, and Urged That of of the War and up to the Present Time Toftjgom Silv Alegbieri: 7 A

14 THE SUN; TUESDAY, ' FEBRUARY' 25, '191?. Inc nried tha Dominion authorities to If TJVTA I IT flmAflUfl MARINE INTELLIGENCE. BY DOMINION FAVORS permit the repayment of the $2,000 In fflftAlllApi ft I IHjIVlJ CANADA DOUBLED CAUTION URGED nlrht annual navments Biter me iirst ' MINIATURE ALMANAC, Gov- - United Suner-Blaml- two years. The second asked tho States Coast and Geodetia srd bo Time. provinces will 6 per crnment to permit such a loan to City of Victoria The be charred FEATURE OF CDRB Fun rls Bun OUTPUT IN 2 YEARSIlb.ci'ssi cent. Interest on the advances from the MAPLE LEAF BANKS LOANS TO SOLDIERS made to a farmer on leased land. It :8JASI sets t.41pi Moon rises 1:03 will twenty years to heinir nntnte.il out that In many cases AM SV2 Bonds fund and bo given niQH WATER THIS DAT. make repayment, or thirty, If necessary. soldiers could lease splendid farms that be purchased for the amounts Eandjr Hook. ..3:03 Alt dor. lsluiit...Si(0 1938-4- 5 Ontario already haa submitted a pro could not XU Due 10th Oct. jien sua M Itc- - gramme for construction on these lines, provided under the loan act. Specialties Advanco in Broad usis a Manufacturing Shows Trade Warned to Await Full Government's Tlan to Estab- LOW WATER THIS DAV. Principal and Interest and British Columbia also baa Intimated Sandy Hook. .:11AM Got. Island:.. A v In Its desire to come In. Quebec and New Trading in the Outside Hell l;ri payable In New York mnrkablo Growth Period Brunswick are among other provinces Outcome of Deliberations lish Veterans on Farms Gat 12:01AM now ISSUES or giving the question their attention. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 2 Chapter 1, CI in World

CI in World War II 113 CHAPTER 1 Counterintelligence In World War II Introduction President Franklin Roosevelts confidential directive, issued on 26 June 1939, established lines of responsibility for domestic counterintelligence, but failed to clearly define areas of accountability for overseas counterintelligence operations" The pressing need for a decision in this field grew more evident in the early months of 1940" This resulted in consultations between the President, FBI Director J" Edgar Hoover, Director of Army Intelligence Sherman Miles, Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral W"S" Anderson, and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A" Berle" Following these discussions, Berle issued a report, which expressed the Presidents wish that the FBI assume the responsibility for foreign intelligence matters in the Western Hemisphere, with the existing military and naval intelligence branches covering the rest of the world as the necessity arose" With this decision of authority, the three agencies worked out the details of an agreement, which, roughly, charged the Navy with the responsibility for intelligence coverage in the Pacific" The Army was entrusted with the coverage in Europe, Africa, and the Canal Zone" The FBI was given the responsibility for the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Central and South America, except Panama" The meetings in this formative period led to a proposal for the organization within the FBI of a Special Intelligence Service (SIS) for overseas operations" Agreement was reached that the SIS would act -

April 2019 Issue 118 Price $9.35 (Incl Gst)

22ND YEAR OF PUBLICATION ESTABLISHED 1998 APRIL 2019 ISSUE 118 PRICE $9.35 (INCL GST) Andrea Bocelli (right) and son Matteo Bocelli Hollywood Icon Sophia Loren Cirque du Soleil A Starry, Starry Night in Southhampton NAMING CEREMONY OF MSC BELLISSIMA Featuring a comprehensive coverage of Global Cruising for Cruise Passengers, the Trade and the Industry www.cruisingnews.com discover what makes Princess #1 cruise line in australia* 4 years running New Zealand 13 Australia & New Zealand 12 Majestic Princess® | Ruby Princess® Nights Majestic Princess® Nights Sydney Bay of Islands Sydney South Pacific Ocean AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIA 2015 - 2018 South Pacific Auckland Ocean Melbourne Auckland Tauranga Tauranga NEW ZEALAND Tasman Tasman Wellington Hobart Sea NEW ZEALAND Sea Akaroa Akaroa Fiordland National Park Dunedin Scenic cruising Dunedin Fiordland National Park (Port Chalmers) Scenic cruising (Port Chalmers) 2019 DEPARTURES 30 Sep, 1 Nov, 14 Nov, 22 Nov 2019 DEPARTURES 15 Dec, 27 DecA 2020 DEPARTURES 8 Jan, 11 Feb, 24 FebA, 8 Mar A Itinerary varies: operates in reverse order 2014 - 2018 A Itinerary varies: operates in reverse order *As voted by Cruise Passenger Magazine, Best Ocean Cruise Line Overall 2015-2018 BOOK NOW! Visit your travel agent | 1300 385 631 | www.princess.com 22ND YEAR OF PUBLICATION ESTABLISHED 1998 APRIL 2019 ISSUE 118 PRICE $9.35 (INCL GST) The Cruise Industry continues to prosper. I attended the handover and naming ceremony recently for the latest MSC ship, MSC Bellissima. It was an incredible four day adventure. Our front cover reveals the big event and you can read reports on page 5 and from page 34. -

The Ghost Ship on the Delaware

The Ghost Ship on the Delaware By Steven Ujifusa For PlanPhilly Thousands pass by the Ghost Ship on the Delaware River every day. They speed past it on Columbus Boulevard, I-95, and the Walt Whitman Bridge. They glance at it while shopping at IKEA. For some, it is just another eyesore on Philadelphia’s desolate waterfront, no different from the moldering old cruisers and troop transports moored in the South Philadelphia Navy Yard. The Ghost Ship on the Delaware. www.ssunitedstatesconservancy.org Some may pull over to the side of the road and take a closer look through a barbed wire fence. They then realize that the Ghost Ship is of a different pedigree than an old troop transport. Its two finned funnels, painted in faded red, white and blue, are dramatically raked back. Its superstructure is low and streamlined, lacking the balconies and large picture windows that make today’s cruise ships look like floating condominiums. Its hull is yacht-like, defined by a thrusting prow and gracefully rounded stern. Looking across the river to Camden, one might see that the hull of the Ghost Ship bears more than a passing resemblance to the low-slung, sweeping one of the battleship U.S.S. New Jersey. This ship is imposing without being ponderous, sleek but still dignified. Even though her engines fell silent almost forty years ago, she still appears to be thrusting ahead at forty knots into the gray seas of the North Atlantic. Finally, if one takes the time to look at the bow of the Ghost Ship, it is clear that she has no ordinary name. -

CMA CGM Updates WAX Service CMA CGM Has Announced New WAX Service Rotation

DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2020 – 288 Number 288 *** COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS *** Wednesday 14-10-2020 News reports received from readers and Internet News articles copied from various news sites. The PORTO awaiting her fate in the port of Niteroi (Brazil) Photo : Capt Jan Plug Master Seven Rio © Distribution : daily to 43.100+ active addresses 14-10-2020 Page 1 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2020 – 288 Your feedback is important to me so please drop me an email if you have any photos / articles that may be of interest to the maritime interested people at sea and ashore PLEASE SEND ALL CORRESPONDENCE / PHOTOS / ARTICLES TO : [email protected] this above email address is monitored 24/7 PLEASE DONT CLICK ON REPLY AS THE NEWSLETTER IS SENt OUT FROM AN UNMANNED SERVER If you don't like to receive this bulletin anymore : please send an e-mail to the above e- mail adress for prompt action your e-mail adress will be deleted ASAP from the server EVENTS, INCIDENTS & OPERATIONS Keppel Smit Towage Pte Ltd 42 ton BP KST 31 navigating the Singapore Strait Photo : Piet Sinke www.maasmondmaritime.com (c) CLICK at the photo & hyperlink in text to view and/or download the photo(s) ! Keppel Smit Towage Pte Ltd was established in 1991 under a joint venture between Keppel Shipyard Investments Pte Ltd [which is a part of Keppel Offshore & Marine under the umbrella of Keppel Corp] and Smit Singapore Pte Ltd [Which is Distribution : daily to 43.100+ active addresses 14-10-2020 Page 2 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2020 – 288 a part of Royal Boskalis Westminster N.V. -

Carnival Corporation & Plc to Transfer AIDA Cruises' Aidablu Cruise Ship

Carnival Corporation & plc to Transfer AIDA Cruises' AIDAblu Cruise Ship to U.K.'s Ocean Village in Spring 2007 August 4, 2005 MIAMI, Aug. 4, 2005 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Carnival Corporation & plc (NYSE: CCL; LSE) (NYSE: CUK) today announced that AIDA Cruises' AIDAblu cruise ship will be transferred to its Ocean Village brand in spring 2007. The transfer follows recent orders for three new 68,500-ton cruise ships for the German brand to be delivered in spring 2007, 2008, and 2009. Additionally, Princess Cruises' Regal Princess, which was originally scheduled to be transferred to Ocean Village, will now remain within the Princess Cruises fleet. "This is an excellent opportunity not only to expand Ocean Village's presence in the U.K. market but also enhance the brand identity of AIDA Cruises. With the addition of these new 68,500-ton cruise ships, AIDA Cruises will be comprised of six modern 'club ships' that cater exclusively to the German- speaking market," said Micky Arison, Carnival Corporation & plc's chairman and CEO. Because the AIDAblu and Ocean Village's current vessel are sister ships and designed to provide an informal, contemporary cruise experience, minimal modifications will be required to convert the AIDAblu to reflect the characteristics of Ocean Village's product. At the same time, Arison noted that retaining the Regal Princess under the Princess Cruises umbrella will enable the brand to maximize its earnings potential. "The strength of the North American cruise market is a compelling reason to keep the Regal Princess within Princess Cruises' fleet. It is one of the world's most successful and recognizable cruise brands and market conditions dictate a need for more capacity, not less," he said. -

An Analysis of Cruise Tourism in the Caribbean and Its Impact on Regional Destination Ports Adrian Hilaire World Maritime University

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 2007 An analysis of cruise tourism in the Caribbean and its impact on regional destination ports Adrian Hilaire World Maritime University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Hilaire, Adrian, "An analysis of cruise tourism in the Caribbean and its impact on regional destination ports" (2007). World Maritime University Dissertations. 349. http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/349 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden AN ANALYSIS OF CRUISE TOURISM IN THE CARIBBEAN AND ITS IMPACT ON REGIONAL DESTINATION PORTS By ADRIAN HILAIRE Saint Lucia A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In MARITIME AFFAIRS (PORT MANAGEMENT) 2007 © Copyright Adrian Hilaire, 2007 Declaration I certify that all material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The content of -

Results for the Quarter Ended 31 March 2002

25 April 2002 P&O PRINCESS CRUISES PLC RESULTS FOR THE QUARTER ENDED 31 MARCH 2002 Key points for the quarter * • Operating profit increased by 29% to $42.2 million, despite the disruption to bookings from the events of 11 September • Pre-tax profit increased by 43% to $27.1 million • Earnings per share/ADS ahead of expectations at 3.7c/$0.15 • Passenger cruise days increased by 13%, including 22% growth in North America • Like for like net revenue yields 8% lower, as forecast in our previous trading update • Underlying unit costs reduced by 11% • Significant planned expansion in UK announced including the launch of a new contemporary brand, Ocean Village Outlook for the remainder of 2002 • Since our last trading update, the pace of bookings for Princess Cruises has remained above 2001 levels, with current pricing now close to last year’s levels • Princess Cruises’ cumulative booking position restored; capacity booked ahead of a year ago but with lower average yields on bookings to date • Booking position remains solid in UK and Australia • Germany growing strongly, with some pressure on yields • Overall like for like yield reduction for the second quarter forecast at 7%, and for the year as a whole 5-6% • On target for 7% reduction in underlying unit costs for the year • Comfortable with analysts’ expectations for full year earnings of 36c-41c per share/$1.44-$1.64 per ADS, excluding merger related costs * comparisons are with the first quarter of 2001 1 Peter Ratcliffe, Chief Executive Officer of P&O Princess Cruises, commented: “Given the disruption to our bookings from the events of 11 September, this is an excellent result. -

Mayor Pins Medals on Police Officers Violent Storm , Sunday Night

16,000 People Read the HERALD. ^ "Justice to all! Published Every Tuesday malice toward none.*1 and Friday Noon. and SUMMIT RECORD FORTY-SECOND YEAR. NO. 79 SUMMIT, N. J., TUESDAY AFTERNOON, JUNE 9, 1931 $3.50 PER YEAR Two Boys Found Here IVmnrrflfc Mayor Pins Medals ffl0C See Congestion Five Children Look Into Mother's Eight- Hiking From Pennsylvania ^ ™S To the Citizens of Summit: on Police Officers Two boys, aged 17 and 15 years, ' . June 8th, 1931. in High Schools Dollar Pay Envelope for Food and Shelter who set out from their homes in r Active Campaign 1 While the effect of the world-wide business depression has Jessop, Pa., to hitch-hike to New been felt in every family in Summit, most of us have been under Calls Local Department York, were picked up by police offi- Local Club Elects Officers the impression that Summit is much better blessed than many School Board Hears of Father Had Two Week^Work During Winter—Co» cers on the Morris turnpike early communities, lacking' as it does, large shutdown industrial plants, Best in State, in Giving Sunday morning and returned home and Hears Talk By •a large transient population of "floaters," and, percentagewise, Increased Enrollment operative Service Budget Exhausted, Has to Look in parental custody. They were County Chairman on 0r= comparatively fewer of the laboring class, and consequently have Next Year—Visit New After Just Such Cases—Children in Case Records Emblems at End oWilliaf m Conely, younger of the ' perhaps been less alive to the desperate condition of a great many two, and William Ford. -

Printmgr File

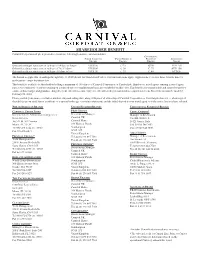

SHAREHOLDER BENEFIT Carnival Corporation & plc is pleased to extend the following benefit to our shareholders: CONTINENTAL NORTH AMERICAN UNITED KINGDOM EUROPEAN AUSTRALIAN BRANDS BRANDS BRANDS BRAND Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 14 days or longer US $250 £125 €200 AUD 250 Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 7 to 13 days+ US $100 £ 50 € 75 AUD 100 Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 6 days or less US $ 50 £ 25 € 40 AUD 50 The benefit is applicable on sailings through July 31, 2010 aboard the brands listed below. Certain restrictions apply. Applications to receive these benefits must be made prior to cruise departure date. This benefit is available to shareholders holding a minimum of 100 shares of Carnival Corporation or Carnival plc. Employees, travel agents cruising at travel agent rates, tour conductors or anyone cruising on a reduced-rate or complimentary basis are excluded from this offer. This benefit is not transferable and cannot be used for casino credits/charges and gratuities charged to your onboard account. Only one onboard credit per shareholder-occupied stateroom. Reservations must be made by February 28, 2010. Please provide your name, reservation number, ship and sailing date, along with proof of ownership of Carnival Corporation or Carnival plc shares (i.e., photocopy of shareholder proxy card, shares certificate or a current brokerage or nominee statement) and the initial deposit to your travel agent or to the cruise line you have selected. NORTH AMERICAN BRANDS UNITED KINGDOM BRANDS CONTINENTAL EUROPEAN BRANDS CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES P&O CRUISES COSTA CRUISES* Guest Solutions Administration Supervisor Reservations Manager Manager of Reservation Guest Services Carnival UK Via XII Ottobre, 2 3655 N.W.