My Story MY NAME

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooma Monaro Final Report 2015

Cooma-Monaro Shire Final Report 2015 Date: 22 October 2015 Cooma-Monaro LGA Final Report 2015 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LGA OVERVIEW Cooma-Monaro Local Government Area The Cooma-Monaro Shire Council area is located in the south east region of NSW. The Shire comprises a land area of approximately 5229 square kilometres comprising undulating to hilly rural grazing land, timbered lifestyle areas and retreat bushland. The Local Government Area (LGA) is adjoined by four other LGAs – Palerang to the north, Tumut and Snowy River to the west, Bombala to the south and Bega Valley to the east. The main economic activities in the Shire include sheep and cattle grazing plus the “provision” of hobby farms / rural home sites in the Cooma area for the Cooma market, in the Michelago area (ie the northern part of the Shire) for the Canberra market and at various other locations including along the Murrumbidgee River and at the southeast periphery near Nimmitabel. These rural/ residential blocks and bush retreats cater for a number of sub markets and demand tends to ebb and flow. Number of properties valued this year and the total land value in dollars The Cooma-Monaro LGA comprises Residential, Rural, Commercial, Industrial, Infrastructure/Special Purposes, Environmental and Public Recreation zones. 5,388 properties were valued at the Base Date of 1 July 2015, and valuations are reflective of the property market at that time. Previous Notices of Valuation issued to owners for the Base Date of 1 July 2014. The Snowy River LGA property market generally has remained static across all sectors with various minor fluctuations. -

Australian Wine Discovered

CHARDONNAY AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED Australia’s unique climate and landscape have fostered a fiercely independent wine scene, home to a vibrant community of growers, winemakers, viticulturists, and vignerons. With more than 100 grape varieties grown across 65 distinct wine regions, we have the freedom to make exceptional wine, and to do it our own way. We’re not beholden by tradition, but continue to push the boundaries in the pursuit of the most diverse, thrilling wines in the world. That’s just our way. AUSTRALIAN CHARDONNAY: T H E EVOLUTION Australian Chardonnay has enjoyed the industry’s highs OF A CLASSIC and weathered its lows with resilience, and it continues to hold a special place for Australian wine lovers. Its Australian journey is a roller‑coaster ride of dramatic proportions. TO DAY - The history of WE’LL Australian Chardonnay - How it’s grown - How it’s made - The different styles - Where it’s grown - Characteristics and flavour profiles COVER… - Chardonnay by numbers THE HISTORY 1908 1969 Tyrrell’s HVD vineyard is Craigmoor’s cuttings OF AUSTRALIAN planted in Hunter Valley, identified as one of now one of the oldest the best Chardonnay CHARDONNAY Chardonnay vineyards clones with European in the world. provenance in Australia. 1820s –1930s 1918 Chardonnay is one of the Chardonnay cuttings from original varieties brought Kaluna Vineyard in Sydney’s to Australia and thrives in Fairfield are given to a Roth the warm, dry climate. family member, who plants them at Craigmoor Vineyards in Mudgee. EARLY 1970s 1980s Consumer preferences A new style of shift to table wines, with 1979 Chardonnay enters the new styles produced, Winemaker Brian Croser wine market. -

Fish River Water Supply Scheme

Nomination of FISH RIVER WATER SUPPLY SCHEME as a National Engineering Landmark Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Nomination Form 4 Owner's Agreement 5 3. Location Map 6 4. Glossary, Abbreviations and Units 8 5. Heritage Assessment 10 5.1 Basic Data 10 5.2 Heritage Significance 11 5.2.1 Historic phase 11 5.2.2 Historic individuals and association 36 5.2.3 Creative or technical achievement 37 5.2.4 Research potential – teaching and understanding 38 5.2.5 Social or cultural 40 5.2.6 Rarity 41 5.2.7 Representativeness 41 6. Statement of Significance 42 7. Proposed Citation 43 8. References 44 9. CD-ROM of this document plus images obtained to date - 1 - - 2 - 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Fish River Water Supply Scheme [FRWS] is a medium size but important water supply with the headwaters in the Central Highlands of NSW, west of the Great Dividing Range and to the south of Oberon. It supplies water in an area from Oberon, north to Portland, Mount Piper Power Station and beyond, and east, across the Great Dividing Range, to Wallerawang town, Wallerawang Power Station, Lithgow and the Upper Blue Mountains. It is the source of water for many small to medium communities, including Rydal, Lidsdale, Cullen Bullen, Glen Davis and Marrangaroo, as well as many rural properties through which its pipelines pass. It was established by Act of Parliament in 1945 as a Trading Undertaking of the NSW State Government. The FRWS had its origins as a result of the chronic water supply problems of the towns of Lithgow, Wallerawang, Portland and Oberon from as early as 1937, which were exacerbated by the 1940-43 drought. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Luise A. Hercus, 1963-1965

Finding aid HERCUS_L08 Sound recordings collected by Luise A. Hercus, 1963-1965 Prepared January 2014 by SL Last updated 30 November 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by those who have obtained permission from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. This collection may only be copied with the permission of Luise Hercus or her representatives. Permission must be sought from Luise Hercus or her representatives as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1963-1965 Extent: 16 sound tape reels (ca. 60 min. each) : analogue, 3 3/4, 7 1/2 ips, mono. ; 5 in. + field tape report sheets Production history These recordings were collected between 1963 and 1965 by linguist Luise Hercus during field trips to Point Pearce, South Australia, Framlingham, Lake Condah, Drouin, Jindivick, Fitzroy, Strathmerton, Echuca, Antwerp and Swan Hill in Victoria, and Dareton, Curlwaa, Wilcannia, Hay, Balranald, Deniliquin and Quaama in New South Wales. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages and songs of the Madhi Madhi, Parnkalla, Kurnai, Gunditjmara, Yorta Yorta, Paakantyi, Ngarigo, Wemba Wemba and Wergaia peoples. -

Vol. 8, No. 1, March 2009 ISSN 1447-4026 La Trobeana Is Kindly Sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell

Journal of the C. J. La Trobe Society Inc. Vol. 8, No. 1, March 2009 ISSN 1447-4026 La Trobeana is kindly sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell LOVELL CHEN ARCHITECTS & HERITAGE CONSULTANTS LOVELL CHEN PTY LTD, 35 LITTLE BOURKE STREET, MELBOURNE 3000, AUSTRALIA Tel +61 (0)3 9667 0800 FAX +61 (0)3 9662 1037 ABN 20 005 803 494 La Trobeana Journal of the C J La Trobe Society Inc. Vol. 8, No. 1, March 2009 Guest Editor: Dianne Reilly ISSN 1447-4026 Editorial Committee Dr Fay Woodhouse, Chair Me Janet Roberts Billett Mrs Loreen Chambers Dr Dianne Reilly For contributions and subscription enquiries contact: The Honorary Secretary The La Trobe Society PO Box 65 Port Melbourne, Vic 3207 Phone: 9646 2112 FRONT COVER Thomas Woolner, 1825 – 1892, sculptor Charles Joseph La Trobe 1853, diam. 24.0cm. Bronze portrait medallion showing the left profile of Charles Joseph La Trobe. Signature and date incised in bronze I.I.: T. Woolner. Sc. 1853:/M La Trobe, Charles Joseph, 1801 – 1875. Accessioned 1894 La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. CONTENTS A Word from the President 1 Forthcoming Events 1 La Trobe’s Birthday 1 Inverleigh Cemetery 1 La Trobe Society/Royal Historical Society AGL Shaw Lecture 2 Annual General Meeting and Annual Dinner 2 Annual Pioneer Service 2 Christmas Cocktails December, 2009 2 A Word from the Treasurer 3 Charlotte Pellet, 1800-1877 4 La Trobe Society Fellowship, 2009-10 10 LA TROBE SOCIETY FELLOWSHIPS – interim reports 10 2007-08 – Dr Frances Thiele 10 2008-09 – Dr Wayne Caldow 11 La Trobe Signage 13 Restoration Of Charlotte Pellet’s Grave 12 A New Version of Ben Bolt 17 Mathilde Chevalier 18 Benjamin Henry La Trobe 18 A New Version of Ben Bolt 19 Untitled-5.indd 1 8/04/2009 11:35:55 AM Untitled-5.indd 2 8/04/2009 11:35:55 AM A Word from the President 2009 promises to be another joint membership of the La Trobe interesting and educational year for Society and the Royal Historical members of the La Trobe Society. -

Tourism Snowy Mountains

Attachment 1 Tourism Snowy Briefing Note Mountains Tourism Snowy Mountains Contact Tourism Snowy Mountains Jo Hearne Executive Officer PO Box 663 JINDABYNE NSW 2627 Email [email protected] Phone 02 6457 2751 Mob 0431 247 994 Web www.snowymountains.com.au Tourism Snowy Mountains - overview The role of Tourism Snowy Mountains (TSM) is first and foremost, that of leadership. TSM aims to achieve tourism growth through creating opportunities for the region as a whole. This will be achieved by strong alliances with key industry, regional partners and government stakeholders. TSM has a vision that The Snowy Mountains will be the best mountain experience in Australia The Snowy Mountains region covers the Local Government Areas of: Snowy River Shire, Cooma-Monaro Shire, Tumbarumba Shire and Tumut Shire which encompasses all of Kosciuszko National Park. To deliver on this vision TSM provides leadership and direction to the region by encouraging innovative activities for both marketing and product development that grow visitation. As the peak tourism body in the region TSM has a dual role in promoting the Snowy Mountains Region as having the best mountain experience in Australia. This is achieved by TSM having both an external focus and an operational role. The external focus is to • Lift and maintain the profile of the Snowy Mountains Region with Federal, State and Local Governments and their agencies to ensure that the Snowy Mountains region is top of mind as tourism destination • Be a spokesperson for the Snowy Mountains Region on regional -

CIE Final Report NSW Regional Snowy

FINAL REPORT Economic development in the Snowy SAP Prepared for Department of Regional NSW April 2021 THE CENTRE FOR INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS www.TheCIE.com.au The Centre for International Economics is a private economic research agency that provides professional, independent and timely analysis of international and domestic events and policies. The CIE’s professional staff arrange, undertake and publish commissioned economic research and analysis for industry, corporations, governments, international agencies and individuals. © Centre for International Economics 2021 This work is copyright. Individuals, agencies and corporations wishing to reproduce this material should contact the Centre for International Economics at one of the following addresses. CANBERRA SYDNEY Centre for International Economics Centre for International Economics Ground Floor, 11 Lancaster Place Level 7, 8 Spring Street Canberra Airport ACT 2609 Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone +61 2 6245 7800 Telephone +61 2 9250 0800 Facsimile +61 2 6245 7888 Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Website www.TheCIE.com.au Website www.TheCIE.com.au DISCLAIMER While the CIE endeavours to provide reliable analysis and believes the material it presents is accurate, it will not be liable for any party acting on such information. Economic development in the Snowy SAP iii Contents Executive summary 1 1 Socio-economic profile of the Snowy Mountains SAP 7 Mapping the Snowy Mountains SAP to current ABS identifiers 7 Labour force analysis 7 Property sales and local development 16 Economic -

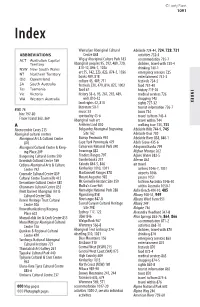

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

The Ecology, Morphology, Distribution and Speciation of a New Species and Subspecies of the Genus Egernia (Lacertilia: Scincidae)

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Cogger, Harold G., 1960. The ecology, morphology, distribution and speciation of a new species and subspecies of the genus Egernia (Lacertilia: Scincidae). Records of the Australian Museum 25(5): 95–105, plates 1 and 2. [1 July 1960]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.25.1960.657 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia VOL. XXV, No. 5 SYDNEY, 1st JULY, 1960 RECORDS of The Australian Museulll (World List abbreviation: Ree. Aust. l\<Ius.) Printed by order of the Trustees Edited by the Director, J. W. EVANS, Sc.D. The Ecology, Morphology, Distribution and Speciation of a New Species and Subspecies of the Genus Egernia (Lacertilia: Scincidae) By HAROLD G. COGGER Pages 95-105 Plates I and II Figs 1-3 Registered at the General Post Office, Sydney, for transmission by post as a periodical • 92265 95 THE ECOLOGY~ MORPHOLOGY~ DISTRIBUTION AND SPECIATION OF A NEW SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES OF THE GENUS EGERNIA (Lacertilia : Scincidae) By HAROLD G. COGGER, Australian Museum (Figs. 1-3) (Plates I and 2) Manuscript Received 13.10.59 SUMMARY A new scincid species (Egernia saxatilis) from the Warrumbungle Mountains, New South Wales, and a new subspecies (Egernia saxatilis intermedia) from Kanangra Walls, New South Wales, are described. Morphological variations in these forms, and in the closely allied Egernia strialata (Peters), are tabulated. Egernia saxatilis saxatilis appears to be confined to the Warrumbungle Mountains, while Egernia saxatilis intermedia is distributed throughout various parts of the eastern highlands. -

Aboriginal Totems

EXPLORING WAYS OF KNOWING, PROTECTING & ACKNOWLEDGING ABORIGINAL TOTEMS ACROSS THE EUROBODALLA SHIRE FAR SOUTH COAST, NSW Prepared by Susan Dale Donaldson Environmental & Cultural Services Prepared for The Eurobodalla Shire Council Aboriginal Advisory Committee FINAL REPORT 2012 THIS PROJECT WAS JOINTLY FUNDED BY COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF INDIGNEOUS CULTURAL & INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS Eurobodalla Shire Council, Individual Indigenous Knowledge Holders and Susan Donaldson. The Eurobodalla Shire Council acknowledges the cultural and intellectual property rights of the Indigenous knowledge holders whose stories are featured in this report. Use and reference of this material is allowed for the purposes of strategic planning, research or study provided that full and proper attribution is given to the individual Indigenous knowledge holder/s being referenced. Materials cited from the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Islander Studies [AIATSIS] ‘South Coast Voices’ collections have been used for research purposes. These materials are not to be published without further consent, which can be gained through the AIATSIS. DISCLAIMER Information contained in this report was understood by the authors to be correct at the time of writing. The authors apologise for any omissions or errors. ACKNOWLEDMENTS The Eurobodalla koori totems project was made possible with funding from the NSW Heritage Office. The Eurobodalla Aboriginal Advisory Committee has guided this project with the assistance of Eurobodalla Shire Council staff - Vikki Parsley, Steve Picton, Steve Halicki, Lane Tucker, Shannon Burt and Eurobodalla Shire Councillors Chris Kowal and Graham Scobie. A special thankyou to Mike Crowley for his wonderful images of the Black Duck [including front cover], to Preston Cope and his team for providing advice on land tenure issues and to Paula Pollock for her work describing the black duck from a scientific perspective and advising on relevant legislation. -

Water Research Laboratory

Water Research Laboratory Never Stand Still Faculty of Engineering School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment WRL Technical Report 2017/09 October 2017 by I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Project Details Report Title Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment Report Author(s) I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Report No. 2017/09 Report Status Final Date of Issue 16 October 2017 WRL Project No. 2014105.01 Project Manager Ian Coghlan Client Name 1 Umwelt Australia Pty Ltd Client Address 1 75 York Street PO Box 3024 Teralba NSW 2284 Client Contact 1 Pam Dean-Jones Client Name 2 Eurobodalla Shire Council Client Address 2 89 Vulcan Street PO Box 99 Moruya NSW 2537 Client Contact 2 Norman Lenehan Client Reference ESC Tender IDs 216510 and 557764 Document Status Version Reviewed By Approved By Date Issued Draft J T Carley G P Smith 9 June 2017 Final Draft J T Carley G P Smith 1 September 2017 Final J T Carley G P Smith 16 October 2017 This report was produced by the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales for use by the client in accordance with the terms of the contract. Information published in this report is available for release only with the permission of the Director, Water Research Laboratory and the client. It is the responsibility of the reader to verify the currency of the version number of this report. -

Aboriginal Spatial Organization in the Study Area

IN QUEST OF NARGUN AND NYOLS: A HISTORY OF INDIGENOUS TOURISM AT THE BUCHAN CAVES RESERVE – Associate Professor Ian D. Clark ABSTRACT description of Duke, O’Rourke, and Dickson (Dixon) caves, and the Spring Creek, Wilson This paper is concerned to document tourism and Creek, and Murrindal caves. He recommended indigenous heritage values associated with the that the Buchan Caves be developed as a tourist Buchan Caves Reserve in Gippsland, Victoria, attraction, along the lines of the Jenolan Caves in Australia. It shows that indigenous values have New South Wales. Stirling made ground plans of not been at the forefront of the development of the the Buchan and neighbouring caves and heliotype tourism product at the Buchan Reserve. The plates from the expedition photographs by J H inattention to Aboriginal values within the Harvey, illustrating views in Wilson and Dickson development of tourism may best be understood caves. The status of these photographs (and as a structural matter, a view from a window others by Harvey not published in the report) has which has been carefully placed to exclude a long been seen as being the first – but a much whole quadrant of the landscape. Indigenous earlier photograph has now come to light and its values of places were rarely discussed because provenance is currently being sought for they were not in the eye of the vision, ‘out of sight’ confirmation (E Hamilton-Smith pers. comm. and ‘out of mind’. Indigenous tourism at Buchan 17/5/2007). does not challenge this understanding. INTRODUCTION This paper is concerned to document tourism and indigenous heritage values associated with the Buchan Caves Reserve in Gippsland, Victoria, Australia.