Introduction Governance and Security in the North- East Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bayero University, Kano

BUK UTME Admission List - Uploaded on www.myschoolgist.com.ng BBAYEROAYERO UNIVERSITY, KANO OfficOfficee of The Registrar DIRECTORATE OF EXAMINATIONS, ADMISSIONS & RECORDS 22016/2017016/2017 UTME ADMISSIONS Faculty of Agriculture B. Agriculture -100590B S/N PS/N UTME No. Full Name 1 1 66173020HD MAILAFIYA MOHAMMED 2 2 65301356EC MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD SANI 3 3 65193024II AHMAD FAIZ KABIR 4 4 66172307HI AHMAD NAFSUZZAKIYA ISAH 5 5 65303336BJ ABDULLAHI FATIMA ALI 6 6 65886647GD DANEIL EMMANUEL SUNDAY 7 7 65550339JA AHMED HAMZA ABUBAKAR 8 8 65875601CH ABBANI ABDULLAHI AMMANI 9 9 66543624HF MUHAMMAD YAHAYA 10 10 65248771HF BELLO ALIYU ALIYU 11 11 65193465CG AMINU AMINU BALA 12 12 66546533HI MUSA AUWAL MIKO 13 13 65193237DB ISHAQ ABDURRAHMAN MANSUR 14 14 65219564AI ASIRU ILIYASU ABDULLAHI 15 15 65881138AD SAGIR SURAJ ISAH 16 16 66547762HH SANI UMMI USMAN 17 17 65235454GC YUSIF USMAN SALISU 18 18 65305219JD YUSUF HUSSAINA TIJJANI 19 19 65528886EB NASIR HASSAN IBRAHIM BUK UTME Admission List - Uploaded on www.myschoolgist.com.ng 20 20 65879081GD MAGASHI ADAMU AMINU 21 21 65885355FJ IDRIS ACHAMAJA JIBRIL 22 22 65898369BB MUHAMMAD BALA SANI 23 23 65295005ID ABDUL ADAMU SABO 24 24 66180675JH UBALE ABDUL GWAMNATI 25 25 65248118JE YAQUB BILYAMINU 26 26 66182381CD HASSAN ABDULRAZAK SALISU 27 27 65882096DJ SHANAWA RUFAI ISAH 28 28 65194550GJ GWADABE USMAN BASHIR 29 29 65196802AG KABIR ABDULMALIK 30 30 66542377DD USMAN ISA 31 31 65879598GE ABDULLAHI ABUBAKAR 32 32 65245787AG MAMUDA SUNUSI 33 33 65887995JD HAFIZ AISHA ABDULYASSAR 34 34 65047384CD NURA ABDULLAHI -

The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015)

Violent Conflict in Divided Societies The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015) Nigeria Conflict Security Analysis Network (NCSAN) World Watch Research November, 2015 [email protected] www.theanalytical.org 1 Violent Conflict in Divided Societies The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015) Taraba State, Nigeria. Source: NCSAN. The Deeper Reality of the Violent Conflict in Taraba State and the Plight of Christians Nigeria Conflict and Security Analysis Network (NCSAN) Working Paper No. 2, Abuja, Nigeria November, 2015 Authors: Abdulbarkindo Adamu and Alupse Ben Commissioned by World Watch Research, Open Doors International, Netherlands No copyright - This work is the property of World Watch Research (WWR), the research department of Open Doors International. This work may be freely used, and spread, but with acknowledgement of WWR. 2 Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge with gratitude all that granted NCSAN interviews or presented documented evidence on the ongoing killing of Christians in Taraba State. We thank the Catholic Secretariat, Catholic Diocese of Jalingo for their assistance in many respects. We also thank the Chairman of the Muslim Council, Taraba State, for accepting to be interviewed during the process of data collection for this project. We also extend thanks to NKST pastors as well as to pastors of CRCN in Wukari and Ibi axis of Taraba State. Disclaimers Hausa-Fulani Muslim herdsmen: Throughout this paper, the phrase Hausa-Fulani Muslim herdsmen is used to designate those responsible for the attacks against indigenous Christian communities in Taraba State. However, the study is fully aware that in most reports across northern Nigeria, the term Fulani herdsmen is also in use. -

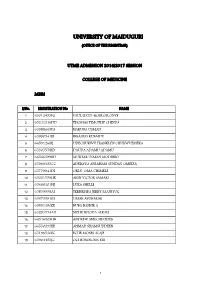

University of Maiduguri Utme Admission

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION FOR 2017/2018 ACADEMIC SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY S/No. Reg. No Name of Candidate 1 76186593GA MUHAMMED MUSABIRA MBBS 2 75616150BI ALI JUMMA'A SA'ADATU MUHAMMAD MBBS 3 75225603JD BELLO MAHASIN MBBS 4 75228686FJ TOGBORESO LOKPANE JAVAV MBBS 5 75234576ED BRUNO O CLEMS MBBS 6 75853832BJ ADEKOYA SEUN MBBS 7 76074976GH HASANA J DANIEL MBBS 8 75072297DH PIUS PAULINUS WARIGASU MBBS 9 75922039GI ABU OLUWAFEMI SUCCESS MBBS 10 75226335DB OLADOSU ABDULRASAQ OLALEKAN MBBS 11 76772693HJ CHARLES ANIYIN MBBS 12 75071512GE NEHEMIAH NGATI ULEA MBBS 13 75596581EA YUNUSA UMAR MBBS 14 77174029DF YUNUSA SHAMSI MBBS 15 75232914IC SHALTUT AHMAD MUHAMMAD MBBS 16 75962393GC GBOGBO JOSEPH OGHENEOCHUKO MBBS 17 76169985CG AMBI YAHAYA SALEH MBBS 18 75343406FF TOBALU FELIX AIGBOKHAI MBBS 19 75230208FC TUMBA CHRISTOPHER SUNDAY MBBS 20 75231817HF PHILIP PRISCILLIA DIBAL MBBS 21 75223796IC OLUKUNLE BOLANLE IRETUNDE MBBS 22 75966302HC UMEH FORTUNE CHIMA MBBS 23 76055844DJ ABASS ABDULLATEEF RAJI MBBS 24 76770023DI UDECHUKWU PROMISE CHIDI MBBS Page 1 of 144 25 75069790IJ JESSE TAIMAKO MBBS 26 75356959DJ ONOJA ANTHONY MATHEW MBBS 27 75475076CJ MUHAMMAD ABBAS BELLO MBBS 28 75225451GE NGGADA SAMUEL DAVID MBBS 29 76770533GA HARUNA ABUBAKAR YIRASO MBBS 30 75229251BD ABDU YUSUF LAWAN MBBS 31 76187405EJ YUSUF FATIMAZARA WASILI MBBS 32 77084690EB OZIGI PIUS JOHN ASUKU MBBS 33 75482315EA MUSA ILIYA MBBS 34 75550189CB TITUS FRIDAY MBBS 35 75174715HJ UMORU HARUNA MAINA MBBS -

Young Achievers 2015

COMMONWEALTH YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 COMMONWEALTH YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 S R CHIEVE A G N OU 2015 Y TH L COMMONWEA TEAM OF THE COMMONWEALTH YOUNGCOMMONWEA LTH ACHIEVERS BOOKYOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 Editorial Team Ahmed Adamu (Nigeria) Tilan M Wijesooriya (Sri Lanka) Ziggy Adam (Seychelles) Jerome Cowans (Jamaica) Melissa Bryant (St. Kitts and Nevis) Layout & Design Abdul Basith (Sri Lanka) © Commonwealth Youth Council, United Kingdom, 2015 Published by: Commonwealth Youth Council, United Kingdom Cover design: Abdul Basith (Sri Lanka) & Akiel Surajdeen (Sri Lanka) Permission is required to reproduce any part of this book CONTENTS Chapter 01 Introduction Page 1 • Preamble • Acknowledgement • Foreword Message from the Chairperson – Commonwealth Youth Council (CYC) • About the CYC • Synopses of CYC Executives Chapter 02 Commonwealth Young Achievers Page 21 • Africa • Asia • Caribbean and Americas • Europe • Pacific TH L COMMONWEA Chapter 03 Youth Development Perspectives Page 279 • Generating Positive Change through Youth 2015 S R CHIEVE A G N OU Y Volunteerism • When people talk, great things happen: The Role of Youth in Peace-building and Social Cohesion • Why Africa’s Youths Are So Passionate about Change • Stop washing your hands of young people…Time for action: Youth and Politics • Youth Entrepreneurship and Overcoming Youth Unemployment • Trialling Youth Ideas on Civic Participation • Youth participation in environment protection Chapter 04 Conclusion and Way Forward Page 323 2015 S TH L R CHIEVE COMMONWEA A G N OU Y OUNG ACHIEVERS Y 2015 COMMONWEALTH COMMONWEALTH YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 Y OU N G A COMMONWEA CHIEVE R L TH S 2015 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION COMMONWEALTH 2015 YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 Years of Vigour and Freshness Ocean of Potentials Unending Efforts and Enthusiasm Tears of Hardships Hope for a Better World PREAMBLE Years of vigour and freshness, Ocean of potentials, Unending efforts and enthusiasm, Tears of hardships, Hope for a better world (YOUTH). -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

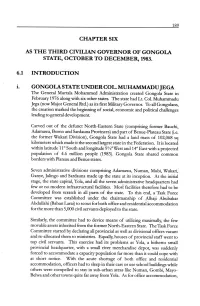

State, Octoberto Decembe& 1983. 6.I Introduction Gongoi-A State Under Col. Muhammaduiega

189 CHAPTER SIX ASTHE THIRD CTVILIAN GOVERNOROF GONGOI.A STATE, OCTOBERTO DECEMBE& 1983. 6.I INTRODUCTION l. GONGOI-A STATE UNDER COL. MUHAMMADUIEGA The General Murtala Mohammed Administration created Gongola State in February 1976 along with six other states. The state had Lt. Col. Muhammadu Jega (now Major General Rtd.) as its fust Military Governor. To all Gongolans, the creation marked the beginning of social, economic and political challenges leading to general development. Carved out of the defunct North-Eastem State (comprising former Bauchi, Adamawa, Borno and Sardauna Provinces) and part of Benue-Plateau State (i.e. the former Wukari Division), Gongola State had a land mass of 102,068 sq kilometers which made it the second latgest state in the Federation. It is located within latitude 11" South and longitude 9%"West and 14" East with a projected population of 4.6 million people (1983). Gongola State shared comnon borders with Plateau and Benue sates. Seven administrative divisions comprising Adamawa, Numan, Mubi, Wukari; Ganye, Jalingo and Sardauna made up the state at its inception. At the initial stage, the st2te capital, Yola, and all the seven adrninistrative headquarters had few or no modern infrastructutal faciiities. Mosi facilities therefore had to be developed from scratch in all parts of the sate. To this end, a Task Fotce Committee was esablished undet the chaitmanship of Alhaji Abubakar Abdullahi @aban Larai) to scout for both of6ce and residential iccommodation for the more than 5,000 civil servants deployed to the state. Similarly, the committee had to device means of srilizilg 6axi6fly, the few movable assets inherited from the former North-Eastern State. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette No. 47 Lagos ~ 29th September, 1977 Vol. 64 CONTENTS Page Page Movements of Officers ” ; 1444-55 “Asaba Inland Postal Agency—Opening of .. 1471 Loss of Local Purchase Orders oe .« 1471 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army— Commissions . 1455-61 Loss of Treasury Receipt Book ‘6 1471 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army— Loss of Cheque . 1471 Compulsory Retirement... 1462 Ministry of Education—Examination in Trade Dispute between Marine’ Drilling , Law, Civil Service Rules, Financial Regu- and Constructions Workers’ Union of lations, Police Orders and Instructions Nigeria and Zapata Marine Service and. Ppractical Palice Work-——December (Nigeria) Limited .e .. 1462. 1977 Series +. 1471-72 -Trade Dispute between Marine Drilling Oyo State of Nigeria Public Service and Construction Workers? Unions of Competition for Entry into the Admini- Nigeria and Transworld Drilling Com-- strative and Special Departmental Cadres pay (Nigeria) Limited . 1462-63 in 1978 , . 1472-73 Constituent Assembly—Elected Candi. Vacancies .- 1473-74 ; dates ~ -» ° 1463-69 Customs and Excise—Dieposal of Un- . Land required for the Service of the _ Claimed Goods at Koko Port o. 1474 Federal Military Government 1469-70 Termination of Oil Prospecting Licences 1470 InpEx To LecaL Notice in SupPLEMENT Royalty on Thorium and Zircon Ores . (1470 Provisional Royalty on Tantalite .. -- 1470 L.N. No. Short Title Page Provisional Royalty on Columbite 1470 53 Currency Offences Tribunal (Proce- Nkpat Enin Postal Agency--Opening of 1471 dure) (Amendment) Rules 1977... B241 1444 - OFFICIAL GAZETTE No. 47, Vol. 64 Government Notice No. 1235 NEW APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER STAFF CHANGES - The following are notified for general information _ NEW APPOINTMENTS Department ”Name ” Appointment- Date of Appointment Customs and Excise A j ~Clerical Assistant 1-2~73 ‘ ‘Adewoyin,f OfficerofCustoms and Excise 25-8-75 Akan: Cleri . -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

Jesus, the Sw, and Christian-Muslim Relations in Nigeria

Conflicting Christologies in a Context of Conflicts: Jesus, the sw, and Christian-Muslim Relations in Nigeria Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum religionum (Dr. rer. rel.) der Theologischen Fakultät der Universität Rostock vorgelegt von Nguvugher, Chentu Dauda, geb. am 10.10.1970 in Gwakshesh, Mangun (Nigeria) aus Mangun Rostock, 21.04.2010 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Klaus Hock Chair: History of Religions-Religion and Society Faculty of Theology, University of Rostock, Germany Examiners Dr. Sigvard von Sicard Honorary Senior Research Fellow Department of Theology and Religion University of Birmingham, UK Prof. Dr. Frieder Ludwig Seminarleiter Missionsseminar Hermannsburg/ University of Goettingen, Germany Date of Examination (Viva) 21.04.2010 urn:nbn:de:gbv:28-diss2010-0082-2 Selbständigkeitserklärung Ich erkläre, dass ich die eingereichte Dissertation selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die von mir angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und die den benutzten Werken wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Statement of Primary Authorship I hereby declare that I have written the submitted thesis independently and without help from others, that I have not used other sources and resources than those indicated by me, and that I have properly marked those passages which were taken either literally or in regard to content from the sources used. ii CURRICULUM VITAE CHENTU DAUDA NGUVUGHER Married, four children 10.10.1970 Born in Gwakshesh, Mangun, Plateau -

Unimaid Utme 2016 2017 First Batch

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION 2016/2017 SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICINE MBBS S/No. REGISTRATION No. NAME 1 65012453FG PAUL LIZZY-ROSE OILONYE 2 65241316DD THOMAS TIMOTHY CHINDA 3 65988663FA HARUNA USMAN 4 65880541EI IBRAHIM KUBAIDU 5 66531268IJ UDECHUKWU FRANKLYN CHUKWUEMEKA 6 65305578ID DAUDA ADAMU ADAMU 7 66546199BD MUKTAR USMAN MODIBBO 8 65989125CC ADEBAYO ABRAHAM SUNDAY OMEIZA 9 65759941DI ORLU-OMA CHIMELE 10 65021759HE AKIN VICTOR SAMARI 11 65488101HJ LUKA SHELLE 12 65859958AI TERHEMBA JERRY SAANIYOL 13 65875581IH UMAR ABUBAKAR 14 65891180EE BUBA BASHIR A 15 65295774AH NUHU RHODA ALKALI 16 66546503HB ANDREW MELCHIZEDEK 17 66550295EE AHMAD SHAMSUDDEEN 18 65198536EC ECHE MOSES ALAJE 19 65904453JC OCHE PRINCESS EHI 1 20 65299718AJ ABDULMUMIN ABUBAKAR 21 65459752FH OBI SOMTO 22 65780434FH JATTO ISA ENERO 23 66200732GG MICHAEL BLESSING 24 66299464BB MICHAEL KISLON SHITNAN 25 65903857DH USMAN ADAMA 26 66215998FC GWASKI ISAAC DIKA 27 66496897JB MOHAMMED ADAMU DUMBULWA 28 65243376GB TAHIR MUHAMMAD ARABO 29 66048182HA JERRY LEAH 30 65885079BE AHMED ABBA 31 65858960JC GAMBO LAWI 32 66246168ED SAMAILA BITRUS VISION 33 65919477CI OBI PETER CHIGOZIE 34 65548790IB GADZAMA JANADA YOHANNA 35 66193123AB MOSES MATTHEW TAIYE 36 65780170HD AERNAN SEDOO 37 65786350GA ZAKARIYYA ABDULMUMIN SANI 38 66324429JH OJIMADU CHIDINDU GODSWILL 39 65527190IF MBAYA ENOCH SAMUEL 40 65199053ED GAGA TERNGUNAN ERIC 41 65534793HB ROBERT RAKEAL 42 65305105EH YAK'OR TONGRIYANG DAWEET 43 65299765GC GONI AISHA UMAR 44 65136595BD AFOLABI ABDULWAHAB -

Alternative Dispute Resolution – the Biu Emirate Mediation Centre

January 2018 Newsletter - Enhancing State and Community Level Conflict Management Capability in North Eastern Nigeria This is a 4-year programme that will enhance state and community level conflict management capability in order to prevent the escalation of conflict into violence across the three North East States of Nigeria – Adamawa, Borno and Yobe. Key Activities – January 2018 Alternative Dispute Resolution in Action – Borno State Traditional Ruler Training – Wives and Scribes/Record Keeping Systems Policy Dialogue Forum Meetings – Yobe and Borno States Continued Community Peace and Safety Platform (CPSPs) Meetings Alternative Dispute Resolution – The Biu Emirate Mediation Centre “Following the recent training we received from Green Horizon Limited under the European Union funded MCN Programme on Alternative Dispute Resolution, which took place in Biu, His Royal Highness the Emir of Biu, Alh. Umar Mustapha Aliyu, was briefed by the facilitators during their visit to the palace. Immediately after the visit, the Emir of Biu on 15 January 2018 established an office known as Dakin Sulhu (Mediation Centre). Mediation commenced at the Centre on 20 January 2018. So far we have mediated and resolved seven cases related to land, community leadership and family issue. A very important one is a case of mediation that settled the difference between two community leaders, Mal Kawo and Mal Magaji. Both of them had been contesting for leadership in their community and had been in dispute for the past 9 years, not even talking to each other. But with the intervention of the Dakin Sulhu, the dispute was laid to rest, and now they live amicably with each other.” Zannan Sulhu of Biu Emirate, head of Biu Emirate Mediation Centre (Dakin Sulhu) 1 Community Leaders shaking hands shortly after a 9-year old quarrel between them was settled at the Dakin Sulhu (Biu Emirate Mediation Centre).