ISOJ Volume 11, Number 1, Spring 2021 #ISOJ Volume 11, Number 1, Spring 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Actions 2/19/2020

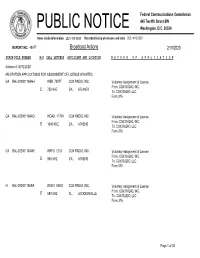

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49677 Broadcast Actions 2/19/2020 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 02/12/2020 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED GA BAL-20200110AAH WSB 73977 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 750 KHZ GA ,ATLANTA To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 GA BAL-20200110AAQ WGAU 11709 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 1340 KHZ GA ,ATHENS To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 GA BAL-20200110AAR WRFC 1218 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 960 KHZ GA ,ATHENS To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 FL BAL-20200110ABA WOKV 53601 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 690 KHZ FL , JACKSONVILLE To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 33 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49677 Broadcast Actions 2/19/2020 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 02/12/2020 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED FL BAL-20200110ABI WDBO 48726 COX RADIO, INC. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Hispanic Media Today Serving Bilingual and Bicultural Audiences in the Digital Age

PUBLIC SQUARE PROGRAM Oscar Ortega / Nuestra Voz Hispanic Media Today Serving Bilingual and Bicultural Audiences in the Digital Age BY JESSICA RETIS MAY 2019 About the Author Jessica Retis is an Associate Professor of Journalism at California State University Northridge. She earned a B.A. in Communications (Lima University, Peru), a master’s in Latin American Studies (UNAM, Mexico), and a Ph.D. in Contemporary Latin America (Complutense University of Madrid, Spain). Her research interests include migration, diasporas and the media, and US Latino & Latin American cultural industries. Her work has been published in journals in Latin America, Europe, and North America. She is co- editor of The Handbook of Diaspora, Media and Culture (Wiley, 2019). Recent book chapters: “Hashtag Jóvenes Latinos: Teaching Civic Advocacy Journalism in Glocal Contexts” (2018); “The transnational restructuring of communication and consumption practices. Latinos in the urban settings of global cities” (2016); and “Latino Diasporas and the Media. Interdisciplinary Approaches to Understand Transnationalism and Communications in Global Cities” (2014). About Democracy Fund Democracy Fund is a private foundation created by eBay founder and philanthropist Pierre Omidyar to help ensure our political system can withstand new challenges and deliver on its promise to the American people. Democracy Fund has invested more than $100 million in support of a healthy democracy, including for modern elections, effective governance, and a vibrant public square. To learn more about Democracy Fund’s work to support engaged journalism, please visit http://www.democracyfund.org. About Our Cover Photo “Nuestra Voz” show is part of the progressive Spanish Language Programming at the alternative and non-comercial radio station “KPFK Pacifica Radio 90.7 FM Los Angeles.” Nuestra Voz (Our Voice) has been on air for more than 16 years, and it has always provided a voice to the Latino community in SoCal, as well as throughout Latin America. -

Impact Report

Impact Report 2011 Clear Channel Communities ™ Impact Report 2011 Contents 2 Clear Channel by the Numbers 4 Executive Letter 7 Local Advisory Boards 8 Power in Numbers: National Radio Campaigns 11 January - March: Musicians On Call & United Negro College Fund 17 April - June: City of Hope & Greater Than AIDS 23 July - September: Muscular Dystrophy Association 27 October - December: Wounded Warrior Project™ 31 9/11 Day of Service 35 St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital 39 Fisher House Foundation 43 StandUp For Kids 49 Local Impact 93 Outdoor 99 Responding to Disasters 105 Welcome to Clear Channel Communities Clear Channel by the Numbers 10 million 150 Public Service Announcements Cities 119,000 850 Public Affairs Shows Radio Stations 60,000 237 hours million Local Interest Programming Monthly Listeners 1,500 1 approx. million LAB Members Outdoor Displays IMPACT REPORT 2011 | 3 Executive Letter Clear Channel has long led the media and entertainment industry in the quantity and scope of our community service programs, whether at the local, regional or national level. At Clear Channel, we believe that we are more than the leading media company in America – we are a community partner with a responsibility to inform, inspire and support neighborhoods across the U.S. Our company-wide dedication to serving the needs of the communities in which we live and work has always been the foundation of our company’s culture, and with your help, we are committed to continuing to grow and improve our efforts year after year. Clear Channel focuses on creating effective programs that address the key underlying causes of today’s most pressing issues. -

Mchenry Tichenor and Mchenry Taylor Tichenor, Sr

McHenry Tichenor and McHenry Taylor Tichenor, Sr. As compiled by Norman Rozeff 1931 It is this year that the Harlingen Star becomes the Valley Morning Star. The Valley Morning Star's plant and office is located at 118 North A Street, a site later occupied by Luby's New England Cafeteria. A small photographer's studio stands between the VMS and Junkin's Furniture to the north. The VMS is owned by the March-Fentress Group but in 1933 is sold to McHenry Tichenor, who came to the Valley from Oklahoma. Tichenor, who came to the Valley in 1930, served as an administrator for the VBH and was a member of the Elks and Rotary. It was his purchase of a radio station here from Judge Hofheinz of Houston that sent him on the road to becoming a multi-millionaire. Several years later Hubert Hudson, father of the 1930s state senator from the area, purchases the VMS along with the Brownsville Herald and McAllen Monitor. Tichenor is said to have paid $50,000 for the VMS and sold it five years later for $125,000. Soon after Hudson builds a new newspaper plant at 213 South 2nd Street and installs an efficient rotary press to supersede the flatbed one. 1941 KGBS (later KGBT) radio owned by the Harbenito Broadcasting Co. opens with a 250 watt signal and a staff of eleven. Popular belief is that McHenry Tichenor gives its call sign the initials of his wife, Geneviere Beryl Smith. GBS however is also George B. Storer, founder of Storer Communications which got its start when this chain service station owner purchased his first station in Toledo, Ohio. -

List of Radio Stations in Texas

Texas portal List of radio stations in Texas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of FCC-licensed AM and FM radio stations in the U.S. state of Texas, which can be sorted by their call signs, broadcast frequencies, cities of license, licensees, or programming formats. Call City of [3] Frequency [1][2] Licensee Format sign License KACU 89.7 FM Abilene Abilene Christian University Public Radio KAGT 90.5 FM Abilene Educational Media Foundation Contemporary Christian KAQD 91.3 FM Abilene American Family Association Southern Gospel KEAN- Townsquare Media Abilene 105.1 FM Abilene Country FM License, LLC Townsquare Media Abilene KEYJ-FM 107.9 FM Abilene Modern Rock License, LLC KGNZ 88.1 FM Abilene Christian Broadcasting Co., Inc. News, Christian KKHR 106.3 FM Abilene Canfin Enterprises, Inc. Tejano Townsquare Media Abilene KMWX 92.5 FM Abilene Adult Contemporary License, LLC Townsquare Media Abilene KSLI 1280 AM Abilene License, LLC Townsquare Media Abilene KULL 100.7 FM Abilene Classic Hits License, LLC Call City of [3] Frequency [1][2] Licensee Format sign License KVVO-LP 94.1 FM Abilene New Life Temple KWKC 1340 AM Abilene Canfin Enterprises, Inc. News/Talk Townsquare Media Abilene KYYW 1470 AM Abilene News/Talk License, LLC KZQQ 1560 AM Abilene Canfin Enterprises, Inc. Sports Talk KDLP-LP 104.7 FM Ace Ace Radio Inc. BPM RGV License Company, KJAV 104.9 FM Alamo Adult Hits L.P. KDRY 1100 AM Alamo Heights KDRY Radio, Inc. Christian Teaching & Preaching KQOS 91.7 FM Albany La Promesa Foundation KIFR 88.3 FM Alice Family Stations, Inc. -

Impact Report 2020

IMPACT REPORT 2020 1 2 2020 — ANNUAL REPORT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPANY OVERVIEW ...........................................................4 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY............................................64 SAVING OUR SELVES ....................................................... 128 EXECUTIVE LETTER ..............................................................6 NATIONAL CENSUS DAY ......................................................66 ALL IN CHALLENGE .........................................................130 COMMITMENT TO COMMUNITY .....................................8 WE ARE ALL HUMAN FOUNDATION .......................................68 VIRTUAL CELEBRATIONS OF SPECIAL MOMENTS.....132 ABOUT IHEARTMEDIA .........................................................10 PRIDE RADIO ....................................................................70 CAN’T CANCEL PRIDE ......................................................134 NATIONAL RADIO CAMPAIGNS .....................................12 SMALL BUSINESS SATURDAY ...............................................72 IHEARTRADIO PROM .......................................................136 THE CHILD MIND INSTITUTE & NAMI .....................................14 GRANTING YOUR CHRISTMAS WISH ......................................74 COMMENCEMENT: SPEECHES FOR THE CLASS OF 2020 .......138 THE PEACEMAKER CORPS ..................................................16 ENVIRONMENTAL ..........................................................76 SUMMER CAMP WITH THE STARS .....................................140 -

For Public Inspection Comprehensive

REDACTED – FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT I. Introduction and Summary .............................................................................................. 3 II. Description of the Transaction ......................................................................................... 4 III. Public Interest Benefits of the Transaction ..................................................................... 6 IV. Pending Applications and Cut-Off Rules ........................................................................ 9 V. Parties to the Application ................................................................................................ 11 A. ForgeLight ..................................................................................................................... 11 B. Searchlight .................................................................................................................... 14 C. Televisa .......................................................................................................................... 18 VI. Transaction Documents ................................................................................................... 26 VII. National Television Ownership Compliance ................................................................. 28 VIII. Local Television Ownership Compliance ...................................................................... 29 A. Rule Compliant Markets ............................................................................................ -

Telemundo Spectrum

SA Rodeo 2019-2020 Media Flowchart AUGUST SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER JANUARY FEBRUARY 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 CAMPAIGNS Entertainer Annct. 1 Entertainer Annct. 2 Entertainer Annct. 3 Entertainer Annct. 4 Final Entertainer Annct. (Dec. 18) Give the Gift Image/Blacksmith Spots Carnival Rodeo After Dark Entertainer Spots Thank You San Antonio VIDEO (A25-54) KABB Fox 29 Spot TV :30s (A25-54) 5 5 9 6 7 8 2 5 1 Spot TV Standalone :15s (A25-54) 10 11 13 11 12 10 3 4 1 Spot TV Bookend :15s (A25-54) 10 10 4 4 4 4 Total Spots 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 15 16 32 27 23 22 9 13 2 Bonus Spots 7 6 4 WOAI Spot TV :30s (A25-54) 2 2 3 3 10 4 4 Spot TV Standalone :15s (A25-54) 5 11 10 10 10 18 7 6 Spot TV Bookend :15s (A25-54) Total Spots 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 13 12 13 13 28 11 10 0 Bonus Spots KENS 5 Spot TV :30s (A25-54) 1 1 1 3 5 3 3 Spot TV Standalone :15s (A25-54) 40 6 6 40 40 20 Spot TV Bookend :15s (A25-54) 12 10 8 6 4 Total Spots 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 52 6 19 53 49 27 0 Bonus Spots 12 12 12 KSAT Spot TV :30s (A25-54) 3 2 2 2 14 5 4 2 Spot TV Standalone :15s (A25-54) 4 3 1 6 29 17 17 10 Spot TV :10s 2 2 2 3 10 3 3 3 Spot TV :07s 1 10 11 9 8 Spot TV Bookend :15s (A25-54) 20 20 18 2 8 6 6 4 Total Spots 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 29 27 23 14 71 42 39 27 0 Bonus Spots 2 12 8 8 8 Univision Spot TV :30s (A25-54) 3 3 2 2 2 3 3 Spot TV Standalone :15s (A25-54) 20 20 8 14 16 20 20 Spot TV :10s 5 5 3 5 5 5 5 Spot TV Bookend :15s (A25-54) Total Spots 0 0 0 0 0 0 28 28 0 0 0 13 21 23 28 28 0 Bonus Spots Viamedia Spot TV -

Kbbt(Fm), Kmyo(Fm)

Annual EEO Public File Report Form Stations: KWEX-DT, KNIC-DT, KCOR-CD, KXTN(AM), KVBH(FM), KROM(FM) KBBT(FM), KMYO(FM) (April 01, 2020 - March 31, 2021) The purpose of this EEO Public File Report (“Report”) is to comply with Section 73.2080(c)(6) of the FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule. This Report has been prepared on behalf of the Station Employment Unit that is comprised of the following station(s): KWEX-DT, KNIC-DT & KCOR-CD, KXTN(AM), KVBH(FM), KROM(FM), KBBT(FM), KMYO(FM) and is required to be placed in the public inspection files of these stations, and posted on their websites, if they have websites. The information contained in this Report covers the time period beginning April 01, 2020 to and including March 31, 2021 (the “Applicable Period”). The FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule requires that this Report contain the following information: 1. A list of all full-time vacancies filled by the Station(s) comprising the Station Employment Unit during the Applicable Period; 2. For each such vacancy, the recruitment source(s) utilized to fill the vacancy (including, if applicable, organizations entitled to notification pursuant to Section 73.2080(c)(1)(ii) of the new EEO Rule, which should be separately identified), identified by name, address, contact person and telephone number; 3. The recruitment source that referred the hiree for each full-time vacancy during the Applicable Period; 4. Data reflecting the total number of persons interviewed for full-time vacancies during the Applicable Period and the total number of interviewees referred by each recruitment source utilized in connection with such vacancies; and 5. -

Texas Media Outlets

Texas Media Outlets Newswire’s Media Database provides targeted media outreach opportunities to key trade journals, publications, and outlets. The following records are related to traditional media from radio, print and television based on the information provided by the media. Note: The listings may be subject to change based on the latest data. ________________________________________________________________________________ Radio Stations 27. KAZI-FM [KAZI 88.7] 1. "Taste of Texas" with Lisa Christi 28. KBCY-FM [99.7FM KBCY] 2. Adam Bomb Nights 29. KBIM-FM [94.9 the Country Giant] 3. ALL REQUEST MUSIC FEED 30. KBNJ-FM [Life Changing] 4. BACK STAGE OL 31. KBNL-FM [Radio Manantial] 5. BANDYT BOY EMPIRE 32. KBPA-FM [103.5 Bob FM] 6. BEYOND THE BOOK 33. KBSO-FM [Texas Radio 94.7] 7. Bob Kingsley's Country Top 40 34. KBST-AM [K-Best AM 1490] 8. Bstraw & PaulyG Show 35. KBUK-FM [K-Buck] 9. CHILL OUT JAZZ 36. KBYG-AM [Big 1400 AM] 10. Chip Howard's Sports Talk 37. KCIX-FM [Mix 106] 11. Country Gold 38. KCKM-AM 12. Cyberline 39. KCPS-AM [KCPS 1150] 13. Datum Line w/ Bruce McCarthy 40. KCRS-FM [103.3 Kiss FM] 14. El Show de Raúl Brindis 41. KCUL-FM 15. Elvis Duran and The Morning Show 42. KCYY-FM [Y100] 16. Fishbowl Radio Network 43. KDET-AM [Community Radio] 17. High Plains Public Radio 44. KDKR-FM [KDKR 91.3] 18. JJ Show 45. KDRP-LP 19. K206CD-FM 46. KEOM-FM [Mesquite Schools Radio] 20. KAAM-AM [Legends 770: 47. KESN-FM [ESPN Dallas 103.3 FM] K-Double-AM] 48. -

Kbbt(Fm), Kmyo(Fm)

Annual EEO Public File Report Form Stations: KWEX-DT, KNIC-DT, KCOR-CD, KXTN(AM), KVBH(FM), KROM(FM), KBBT(FM), KMYO(FM) (April 01, 2019 - March 31, 2020) The purpose of this EEO Public File Report (“Report”) is to comply with Section 73.2080(c)(6) of the FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule. This Report has been prepared on behalf of the Station Employment Unit that is comprised of the following station(s): KWEX-DT, KNIC-DT & KCOR-CD, KXTN(AM), KVBH(FM), KROM(FM), KBBT( FM), KMYO(FM) and is required to be placed in the public inspection files of these stations, and posted on their websites, if they have websites. The information contained in this Report covers the time period beginning April 01, 2019 to and including March 31, 2020 (the “Applicable Period”). The FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule requires that this Report contain the following information: 1. A list of all full-time vacancies filled by the Station(s) comprising the Station Employment Unit during the Applicable Period; 2. For each such vacancy, the recruitment source(s) utilized to fill the vacancy (including, if applicable, organizations entitled to notification pursuant to Section 73.2080(c)(1)(ii) of the new EEO Rule, which should be separately identified), identified by name, address, contact person and telephone number; 3. The recruitment source that referred the hire for each full-time vacancy during the Applicable Period; 4. Data reflecting the total number of persons interviewed for full-time vacancies during the Applicable Period and the total number of interviewees referred by each recruitment source utilized in connection with such vacancies; and 5.