11 Surface of the Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY and REALITY Arlin P

The Astrophysical Journal, 697:1–15, 2009 May 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/1 C 2009. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY AND REALITY Arlin P. S. Crotts Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, 550 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA Received 2007 June 27; accepted 2009 February 20; published 2009 April 30 ABSTRACT Transient lunar phenomena (TLPs) have been reported for centuries, but their nature is largely unsettled, and even their existence as a coherent phenomenon is controversial. Nonetheless, TLP data show regularities in the observations; a key question is whether this structure is imposed by processes tied to the lunar surface, or by terrestrial atmospheric or human observer effects. I interrogate an extensive catalog of TLPs to gauge how human factors determine the distribution of TLP reports. The sample is grouped according to variables which should produce differing results if determining factors involve humans, and not reflecting phenomena tied to the lunar surface. Features dependent on human factors can then be excluded. Regardless of how the sample is split, the results are similar: ∼50% of reports originate from near Aristarchus, ∼16% from Plato, ∼6% from recent, major impacts (Copernicus, Kepler, Tycho, and Aristarchus), plus several at Grimaldi. Mare Crisium produces a robust signal in some cases (however, Crisium is too large for a “feature” as defined). TLP count consistency for these features indicates that ∼80% of these may be real. Some commonly reported sites disappear from the robust averages, including Alphonsus, Ross D, and Gassendi. -

October 2006

OCTOBER 2 0 0 6 �������������� http://www.universetoday.com �������������� TAMMY PLOTNER WITH JEFF BARBOUR 283 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 1 In 1897, the world’s largest refractor (40”) debuted at the University of Chica- go’s Yerkes Observatory. Also today in 1958, NASA was established by an act of Congress. More? In 1962, the 300-foot radio telescope of the National Ra- dio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) went live at Green Bank, West Virginia. It held place as the world’s second largest radio scope until it collapsed in 1988. Tonight let’s visit with an old lunar favorite. Easily seen in binoculars, the hexagonal walled plain of Albategnius ap- pears near the terminator about one-third the way north of the south limb. Look north of Albategnius for even larger and more ancient Hipparchus giving an almost “figure 8” view in binoculars. Between Hipparchus and Albategnius to the east are mid-sized craters Halley and Hind. Note the curious ALBATEGNIUS AND HIPPARCHUS ON THE relationship between impact crater Klein on Albategnius’ southwestern wall and TERMINATOR CREDIT: ROGER WARNER that of crater Horrocks on the northeastern wall of Hipparchus. Now let’s power up and “crater hop”... Just northwest of Hipparchus’ wall are the beginnings of the Sinus Medii area. Look for the deep imprint of Seeliger - named for a Dutch astronomer. Due north of Hipparchus is Rhaeticus, and here’s where things really get interesting. If the terminator has progressed far enough, you might spot tiny Blagg and Bruce to its west, the rough location of the Surveyor 4 and Surveyor 6 landing area. -

11 Surface of the Moon

Name: Date: 11 Surface of the Moon 11.1 Introduction One can learn a lot about the Moon by looking at the lunar surface. Even before astronauts landed on the Moon, scientists had enough data to formulate theories about the formation and evolution of the Earth’s only natural satellite. However, since the Moon rotates once for every time it orbits around the Earth, we can only see one side of the Moon from the surface of the Earth. Until spacecraft were sent to orbit the Moon, we only knew half the story. The type of orbit our Moon makes around the Earth is called a synchronous orbit. This phenomenon is shown graphically in Figure 11.1 below. If we imagine that there is one large mountain on the hemisphere facing the Earth (denoted by the small triangle on the Moon), then this mountain is always visible to us no matter where the Moon is in its orbit. As the Moon orbits around the Earth, it turns slightly so we always see the same hemisphere. Figure 11.1: The Moon’s synchronous orbit. (Not drawn to scale.) On the Moon, there are extensive lava flows, rugged highlands and many impact craters of all sizes. The overlapping of these features implies relative ages. Because of the lack of ongoing mountain building processes, or weathering by wind and water, the accumulation of volcanic processes and impact cratering is readily visible. Thus by looking at the images of the Moon, one can trace the history of the lunar surface. 139 • Lab Goals: to discuss the Moon’s terrain, craters, and the theory of relative ages; to use pictures of the Moon to deduce relative ages and formation processes of surface features • Materials: Moon pictures, ruler, calculator 11.2 Craters and Maria A crater is formed when a meteor from space strikes the lunar surface. -

What's Hot on the Moon Tonight?: the Ultimate Guide to Lunar Observing

What’s Hot on the Moon Tonight: The Ultimate Guide to Lunar Observing Copyright © 2015 Andrew Planck All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any written, electronic, recording, or photocopying without written permission of the publisher or author. The exception would be in the case of brief quotations embodied in the critical articles or reviews and pages where permission is specifically granted by the publisher or author. Although every precaution has been taken to verify the accuracy of the information contained herein, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for damages that may result from the use of information contained within. Books may be purchased by contacting the publisher or author through the website below: AndrewPlanck.com Cover and Interior Design: Nick Zelinger (NZ Graphics) Publisher: MoonScape Publishing, LLC Editor: John Maling (Editing By John) Manuscript Consultant: Judith Briles (The Book Shepherd) ISBN: 978-0-9908769-0-8 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2014918951 1) Science 2) Astronomy 3) Moon Dedicated to my wife, Susan and to my two daughters, Sarah and Stefanie Contents Foreword Acknowledgments How to Use this Guide Map of Major Seas Nightly Guide to Lunar Features DAYS 1 & 2 (T=79°-68° E) DAY 3 (T=59° E) Day 4 (T=45° E) Day 5 (T=24° E.) Day 6 (T=10° E) Day 7 (T=0°) Day 8 (T=12° W) Day 9 (T=21° W) Day 10 (T= 28° W) Day 11 (T=39° W) Day 12 (T=54° W) Day 13 (T=67° W) Day 14 (T=81° W) Day 15 and beyond Day 16 (T=72°) Day 17 (T=60°) FINAL THOUGHTS GLOSSARY Appendix A: Historical Notes Appendix B: Pronunciation Guide About the Author Foreword Andrew Planck first came to my attention when he submitted to Lunar Photo of the Day an image of the lunar crater Pitatus and a photo of a pie he had made. -

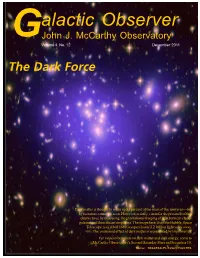

Alactic Observer Gjohn J

alactic Observer GJohn J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 4, No. 12 December 2011 The Dark Force Dark matter is thought to make up 83 percent of the mass of the universe—but by its nature cannot be seen. However, science can infer the presence of this elusive force by measuring the gravitational warping of light between cluster galaxies and their distant neighbors. The image here, from the Hubble Space Telescope, is of Abell 1689, a super cluster 2.2 billion light years away. The presumed effect of dark matter is represented by blue overlay. For more information on dark matter and dark energy, come to McCarthy Observatory's Second Saturday Stars on December 10. Source: NASA/ESA/JPL-Caltech/Yale/CNRS The John J. McCarthy Observatory Galactic Observvvererer New Milford High School Editorial Committee 388 Danbury Road Managing Editor New Milford, CT 06776 Bill Cloutier Phone/Voice: (860) 210-4117 Production & Design Phone/Fax: (860) 354-1595 Allan Ostergren www.mccarthyobservatory.org Website Development John Gebauer JJMO Staff Josh Reynolds It is through their efforts that the McCarthy Observatory has Technical Support established itself as a significant educational and recreational Bob Lambert resource within the western Connecticut community. Dr. Parker Moreland Steve Barone Allan Ostergren Colin Campbell Cecilia Page Dennis Cartolano Bruno Ranchy Mike Chiarella Josh Reynolds Route Jeff Chodak Barbara Richards Bill Cloutier Monty Robson Charles Copple Don Ross Randy Fender Ned Sheehey John Gebauer Gene Schilling Elaine Green Diana Shervinskie Tina Hartzell Katie Shusdock Tom Heydenburg Jon Wallace Phil Imbrogno Bob Willaum Bob Lambert Paul Woodell Dr. Parker Moreland Amy Ziffer In This Issue THE YEAR OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM ................................... -

Arxiv:0706.3947V1

Transient Lunar Phenomena: Regularity and Reality Arlin P.S. Crotts Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, 550 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027 ABSTRACT Transient lunar phenomena (TLPs) have been reported for centuries, but their nature is largely unsettled, and even their existence as a coherent phenomenon is still controversial. Nonetheless, a review of TLP data shows regularities in the observations; a key question is whether this structure is imposed by human observer effects, terrestrial atmospheric effects or processes tied to the lunar surface. I interrogate an extensive catalog of TLPs to determine if human factors play a determining role in setting the distribution of TLP reports. We divide the sample according to variables which should produce varying results if the determining factors involve humans e.g., historical epoch or geographical location of the observer, and not reflecting phenomena tied to the lunar surface. Specifically, we bin the reports into selenographic areas (300 km on a side), then construct a robust average count for such “pixels” in a way discarding discrepant counts. Regardless of how we split the sample, the results are very similar: roughly 50% of the report count originate from the crater Aristarchus and vicinity, 16% from Plato, 6% from recent, major impacts (Copernicus, ∼ ∼ Kepler and Tycho - beyond Aristarchus), plus a few at Grimaldi. Mare Crisium produces a robust signal for three of five averages of up to 7% of the reports (however, Crisium subtends more than one pixel). The consistency in TLP report counts for specific features on this list indicate that 80% of the reports arXiv:0706.3947v1 [astro-ph] 27 Jun 2007 ∼ are consistent with being real (perhaps with the exception of Crisium). -

Lunar Club Observations

Guys & Gals, Here, belatedly, is my Christmas present to you. I couldn’t buy each of you a lunar map, so I did the next best thing. Below this letter you’ll find a guide for observing each of the 100 lunar features on the A. L.’s Lunar Club observing list. My guide tells you what the features are, where they are located, what instrument (naked eyes, binoculars or telescope) will give you the best view of them and what you can expect to see when you find them. It may or may not look like it, but this project involved a massive amount of work. In preparing it, I relied heavily on three resources: *The lunar map I used to determine which quadrant of the Moon each feature resides in is the laminated Sky & Telescope Lunar Map – specifically, the one that shows the Moon as we see it naked-eye or in binoculars. (S&T also sells one with the features reversed to match the view in a refracting telescope for the same price.); and *The text consists of information from (a) my own observing notes and (b) material in Ernest Cherrington’s Exploring the Moon Through Binoculars and Small Telescopes. Both the map and Cherrington’s book were door prizes at our Dec. Christmas party. My goal, of course, is to get you interested in learning more about our nearest neighbor in space. The Moon is a fascinating and lovely place, and one that all too often is overlooked by amateur astronomers. But of all the objects in the night sky, the Moon is the most accessible and easiest to observe. -

January 2018

The StarGazer http://www.raclub.org/ Newsletter of the Rappahannock Astronomy Club No. 3, Vol. 6 November 2017–January 2018 Field Trip to Randolph-Macon College Keeble Observatory By Jerry Hubbell and Linda Billard On December 2, Matt Scott, Jean Benson, Bart and Linda Billard, Jerry Hubbell, and Peter Orlowski joined Scott Lansdale to tour the new Keeble Observatory at his alma mater, Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, VA. The Observatory is a cornerstone instrument in the College's academic minor program in astrophysics and is also used for student and faculty research projects. At the kind invitation of Physics Professor George Spagna— Scott’s advisor during his college days and now the director of the new facility—we received a private group tour. We stayed until after dark to see some of its capabilities. Keeble Observatory at Randolph-Macon College Credit: Jerry Hubbell The observatory, constructed in summer 2017, is connected to the northeast corner of the Copley Science Center on campus. It houses a state-of-the-art $30,000 Astro Systeme Austria (ASA) Ritchey-Chretien telescope with a 16-inch (40-cm) primary mirror. Instrumentation will eventually include CCD cameras for astrophotography and scientific imaging, and automation for the 12-foot (3.6-m) dome. The mount is a $50,000 ASA DDM 160 Direct Drive system placed on an interesting offset pier system that allows the mount to track well past the meridian without having to do the pier-flip that standard German equatorial mounts (GEMs) perform when approaching the meridian. All told, the fully outfitted observatory will be equipped with about $100,000 of instrumentation and equipment. -

The W.A.S.P the Warren Astronomical Society Paper

Vol. 49, no. 3 March, 2018 The W.A.S.P The Warren Astronomical Society Paper President Jeff MacLeod [email protected] The Warren Astronomical Society First Vice President Jonathan Kade [email protected] Second Vice President Joe Tocco [email protected] Founded: 1961 Treasurer Ruth Huellmantel [email protected] Secretary Parker Huellmantel [email protected] P.O. Box 1505 Outreach Diane Hall [email protected] Warren, Michigan 48090-1505 Publications Brian Thieme [email protected] www.warrenastro.org Entire board [email protected] Astronomy at the Beach Dr. Mark Christensen presents “The James Webb Space Telescope” pg. 6 Six out of 18 mirrors of the James Webb Space Telescope being subjected to temperature dipping test | Image source: Wikipedia 1 Society Meeting Times Astronomy presentations and lectures twice each month at 7:30 PM: First Monday at Cranbrook Institute of Science. Third Thursday at Macomb Community College - South Campus Building J (Library) March Discussion Group Note: for the summer, we are meeting in room 151, lower level of the library. Meeting Come on over, and talk astronomy, space Snack Volunteer news, and whatnot! Schedule We will celebrate the Equinox with cheap red! M a r 5 C ran b r o o k Ruth Huellmantel Mar 15 Macomb Jeff MacLeod The Discussion Group for March 22, at 7:30pm Apr 2 Cranbrook Ken Bertin Eastern, will be hosted by Gary M. Ross at his home in Royal Oak. If you are unable to bring the snacks on your scheduled day, or if you need to reschedule, 1828 North Lafayette, Royal Oak please email the board at board@ warrenastro.org as soon as you are able so Four houses north of Twelve Mile Road in the that other arrangements can be made. -

11 Surface of the Moon

Name: Date: 11 Surface of the Moon 11.1 Introduction One can learn a lot about the Moon by looking at the lunar surface. Even before astronauts landed on the Moon, scientists had enough data to formulate theories about the formation and evolution of the Earth’s only natural satellite. However, since the Moon rotates once for every time it orbits around the Earth, we can only see one side of the Moon from the surface of the Earth. Until spacecraft were sent to orbit the Moon, we only knew half the story. The type of orbit our Moon makes around the Earth is called a synchronous orbit. This phenomenon is shown graphically in Figure 11.1 below. If we imagine that there is one large mountain on the hemisphere facing the Earth (denoted by the small triangle on the Moon), then this mountain is always visible to us no matter where the Moon is in its orbit. As the Moon orbits around the Earth, it turns slightly so we always see the same hemisphere. Figure 11.1: The Moon’s synchronous orbit. (Not drawn to scale.) On the Moon, there are extensive lava flows, rugged highlands and many impact craters of all sizes. The overlapping of these features implies relative ages. Because of the lack of ongoing mountain building processes, or weathering by wind and water, the accumulation of volcanic processes and impact cratering is readily visible. Thus by looking at the images of the Moon, one can trace the history of the lunar surface. 139 Lab Goals: to discuss the Moon’s terrain, craters, and the theory of relative ages; to • use pictures of the Moon to deduce relative ages and formation processes of surface features Materials: Moon pictures, ruler, calculator • 11.2 Craters and Maria Acraterisformedwhenameteorfromspacestrikesthelunarsurface.Theforceofthe impact obliterates the meteorite and displaces part of the Moon’s surface, pushing the edges of the crater up higher than the surrounding rock. -

SELENOLOGY the Journal of the American Lunar Society

DEVOTED TO THE STUDY OF EARTH’S MOON VOL. 26 NO. 2 SUMMER 2007 SELENOLOGY The Journal of The American Lunar Society Selenology Vol. 26 No. 2 - Summer 2007 The official journal of the American Lunar Society, an organization devoted to the observation and discovery of the earth’s moon TABLE OF CONTENTS: Cassini A and the Washbowl: As Described by Wilkins and Moore ......... 2 On Closer Examination .......................................................................... 6 Vertical Displacement of Features in the Montes Spitzbergensis Area ....... 15 COVER: Cassini Crater imaged by Wes Higgins on August, 25 2005 at 10:45 UT with a 45 cm Newtonian telescope. Selenology, Vol. 26 No. 2, Summer 2007. A publication of the American Lunar Society. President: Eric Douglass; Vice President: Steve Boint; Editor: Francis G. Graham. Web site: http://amlunsoc.org/ Layout/design by A Distant Wind (www.distantwind.com) This issue edited by Steve Boint. Copyright © 2007 by the American Lunar Society and individual authors; all rights reserved. Send manuscripts, general observations, photographs, drawings and other correspondence to: Steve Boint, VP ALS, 1807 S. Spring Ave., Sioux Falls, SD 57105 E-mail: [email protected] Send changes of address to Eric Douglass at [email protected] If you don’t have e-mail, send them to Steve Boint Page 2 SELENOLOGY Vol. 26 No. 2 Cassini A and the Washbowl: As Described by Wilkins and Moore By Raffaello Lena, Maria Teresa Bregante, Eric Douglass and Giorgio Mengoli GLR group 1. INTRODUCTION degrees. When the colongitude In this article, we report on is the same, on different several observations made by cycles, the lighting conditions the Geologic Lunar Research are similar.