Arxiv:0706.3947V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grosvenor Prints CATALOGUE for the ABA FAIR 2008

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books CATALOGUE FOR THE ABA FAIR 2008 Arts 1 – 5 Books & Ephemera 6 – 119 Decorative 120 – 155 Dogs 156 – 161 Historical, Social & Political 162 – 166 London 167 – 209 Modern Etchings 210 – 226 Natural History 227 – 233 Naval & Military 234 – 269 Portraits 270 – 448 Satire 449 – 602 Science, Trades & Industry 603 – 640 Sports & Pastimes 641 – 660 Foreign Topography 661 – 814 UK Topography 805 - 846 Registered in England No. 1305630 Registered Office: 2, Castle Business Village, Station Road, Hampton, Middlesex. TW12 2BX. Rainbrook Ltd. Directors: N.C. Talbot. T.D.M. Rayment. C.E. Ellis. E&OE VAT No. 217 6907 49 GROSVENOR PRINTS Catalogue of new stock released in conjunction with the ABA Fair 2008. In shop from noon 3rd June, 2008 and at Olympia opening 5th June. Established by Nigel Talbot in 1976, we have built up the United Kingdom’s largest stock of prints from the 17th to early 20th centuries. Well known for our topographical views, portraits, sporting and decorative subjects, we pride ourselves on being able to cater for almost every taste, no matter how obscure. We hope you enjoy this catalogue put together for this years’ Antiquarian Book Fair. Our largest ever catalogue contains over 800 items, many rare, interesting and unique images. We have also been lucky to purchase a very large stock of theatrical prints from the Estate of Alec Clunes, a well known actor, dealer and collector from the 1950’s and 60’s. -

Geoscience and a Lunar Base

" t N_iSA Conference Pubhcatmn 3070 " i J Geoscience and a Lunar Base A Comprehensive Plan for Lunar Explora, tion unclas HI/VI 02907_4 at ,unar | !' / | .... ._-.;} / [ | -- --_,,,_-_ |,, |, • • |,_nrrr|l , .l -- - -- - ....... = F _: .......... s_ dd]T_- ! JL --_ - - _ '- "_r: °-__.......... / _r NASA Conference Publication 3070 Geoscience and a Lunar Base A Comprehensive Plan for Lunar Exploration Edited by G. Jeffrey Taylor Institute of Meteoritics University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico Paul D. Spudis U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Astrogeology Flagstaff, Arizona Proceedings of a workshop sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., and held at the Lunar and Planetary Institute Houston, Texas August 25-26, 1988 IW_A National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Management Scientific and Technical Information Division 1990 PREFACE This report was produced at the request of Dr. Michael B. Duke, Director of the Solar System Exploration Division of the NASA Johnson Space Center. At a meeting of the Lunar and Planetary Sample Team (LAPST), Dr. Duke (at the time also Science Director of the Office of Exploration, NASA Headquarters) suggested that future lunar geoscience activities had not been planned systematically and that geoscience goals for the lunar base program were not articulated well. LAPST is a panel that advises NASA on lunar sample allocations and also serves as an advocate for lunar science within the planetary science community. LAPST took it upon itself to organize some formal geoscience planning for a lunar base by creating a document that outlines the types of missions and activities that are needed to understand the Moon and its geologic history. -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Feature of the Month – January 2016 Galilaei

A PUBLICATION OF THE LUNAR SECTION OF THE A.L.P.O. EDITED BY: Wayne Bailey [email protected] 17 Autumn Lane, Sewell, NJ 08080 RECENT BACK ISSUES: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html FEATURE OF THE MONTH – JANUARY 2016 GALILAEI Sketch and text by Robert H. Hays, Jr. - Worth, Illinois, USA October 26, 2015 03:32-03:58 UT, 15 cm refl, 170x, seeing 8-9/10 I sketched this crater and vicinity on the evening of Oct. 25/26, 2015 after the moon hid ZC 109. This was about 32 hours before full. Galilaei is a modest but very crisp crater in far western Oceanus Procellarum. It appears very symmetrical, but there is a faint strip of shadow protruding from its southern end. Galilaei A is the very similar but smaller crater north of Galilaei. The bright spot to the south is labeled Galilaei D on the Lunar Quadrant map. A tiny bit of shadow was glimpsed in this spot indicating a craterlet. Two more moderately bright spots are east of Galilaei. The western one of this pair showed a bit of shadow, much like Galilaei D, but the other one did not. Galilaei B is the shadow-filled crater to the west. This shadowing gave this crater a ring shape. This ring was thicker on its west side. Galilaei H is the small pit just west of B. A wide, low ridge extends to the southwest from Galilaei B, and a crisper peak is south of H. Galilaei B must be more recent than its attendant ridge since the crater's exterior shadow falls upon the ridge. -

TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY and REALITY Arlin P

The Astrophysical Journal, 697:1–15, 2009 May 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/1 C 2009. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY AND REALITY Arlin P. S. Crotts Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, 550 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA Received 2007 June 27; accepted 2009 February 20; published 2009 April 30 ABSTRACT Transient lunar phenomena (TLPs) have been reported for centuries, but their nature is largely unsettled, and even their existence as a coherent phenomenon is controversial. Nonetheless, TLP data show regularities in the observations; a key question is whether this structure is imposed by processes tied to the lunar surface, or by terrestrial atmospheric or human observer effects. I interrogate an extensive catalog of TLPs to gauge how human factors determine the distribution of TLP reports. The sample is grouped according to variables which should produce differing results if determining factors involve humans, and not reflecting phenomena tied to the lunar surface. Features dependent on human factors can then be excluded. Regardless of how the sample is split, the results are similar: ∼50% of reports originate from near Aristarchus, ∼16% from Plato, ∼6% from recent, major impacts (Copernicus, Kepler, Tycho, and Aristarchus), plus several at Grimaldi. Mare Crisium produces a robust signal in some cases (however, Crisium is too large for a “feature” as defined). TLP count consistency for these features indicates that ∼80% of these may be real. Some commonly reported sites disappear from the robust averages, including Alphonsus, Ross D, and Gassendi. -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

B. Apollo 16 Regional Geologic Setting

B. APOLLO 16REGIONAL GEOLOGIC SETTING By CARROLL ANN HODGES CONTENTS Page Geography 6 Geologic description of Cayley plains and Descartes mountains 6 Relation in time and space to basins and craters 8 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Composite photograph of the lunar near side showing geographic features and multiring basins 7 2. Photographic mosaic of Apollo 16 landing site and vicinity 8 GEOGRAPHY Soderblom and Boyce,1972). The type area of the Cayley Formation is east of the crater Cayley, north of Apollo 16 landed at approximately 15”30’ E., 9” S. on the landing site (Morris and Wilhelms, 1967); the the relatively level Cayley plains, adjacent to the rug- name was extended to the apparently similar plains ged Descartes mountains (Milton, 1972; Hodges, material at the Apollo 16 site (Milton, 1972; Hodges, 1972a). Approximately 70 km east is the west-facing 1972a). These materials were presumed to be represen- escarpment of the Kant plateau, part of the uplifted tative of the widespread photogeologic unit, Imbrian third ring of the Nectaris basin and topographically light plains, which covers about 5 percent of the lunar the highest area on the lunar near side. With respect to highlands surface (Wilhelms and McCauley, 1971; the centers of the three best-developed multiringed Howard and others, 1974). Characteristics include rel- basins, the site is about 600 km west of Nectaris, 1,600 atively level surfaces, intermediate albedo, and nearly km southeast of Imbrium, and 3,500 km east-northeast identical crater size-frequency distributions. of Orientale. The nearest mare materials are in The plains were first interpreted as smooth facies of Tranquillitatis, about 300 km north (fig.1). -

Facts for the Times

Valuable Historical Extracts. ,,,,,,, 40,11/1/, FACTS FOR THE TIMES. A COLLECTION —OF — VALUABLE HISTORICAL EXTRACTS ON A GR.E!T VA R TETY OF SUBJECTS, OF SPECIAL INTEREST TO THE BIBLE STUDENT, FROM EMINENT AUTHORS, ANCIENT AND MODERN. REVISED BY G. I. BUTLER. " Admissions in favor of troth, from the ranks of its enemies, constitute the highest kind of evidence."—Puss. Ass Mattatc. Pr This Volume contains about One Thousand Separate Historical Statements. THIRD EDITION, ENLARGED, AND BROUGHT DOWN TO 1885. REVIEW AND HERALD, BATTLE CREEK, MICH. PACIFIC PRESS, OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA. PREFACE. Tax object of this volume, as its name implies, is to furnish to the inquirer a large fund of facts bearing upon important Bible subjects, which are of special interest to the present generation, • While "the Bible and the Bible alone" is the only unerring rule of faith and practice, it is very desirable oftentimes to ascertain what great and good men have believed concerning its teachings. This is especially desirable when religious doctrines are being taught which were considered new and strange by some, but which, in reality, have bad the sanction of many of the most eminent and devoted of God's servants in the past. Within the last fifty years, great changes have occurred among religious teachers and churches. Many things which were once con- sidered important truths are now questioned or openly rejected ; while other doctrines which are thought to be strange and new are found to have the sanction of the wisest and best teachers of the past. The extracts contained in this work cover a wide range of subjects, many of them of deep interest to the general reader. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

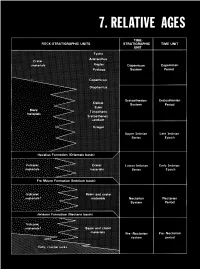

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing