Old Town Triangle District Commercial Building Historic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois Street

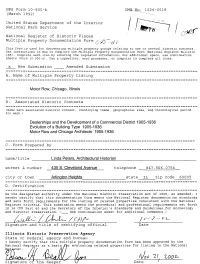

NFS Form 10-900-b OMR..Np. 1024-0018 (March 1992) / ~^"~^--.~.. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / / v*jf f ft , I I / / National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form /..//^' -A o C_>- f * f / *•• This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Dealerships and the Development of a Commercial District 1905-1936 Evolution of a Building Type 1905-1936 Motor Row and Chicago Architects 1905-1936 C. Form Prepared by name/title _____Linda Peters. Architectural Historian______________________ street & number 435 8. Cleveland Avenue telephone 847.506.0754 city or town ___Arlington Heights________________state IL zip code 60005 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

1650 N Wells St Chicago, Il 60614

OLD TOWN RETAIL / OFFICE / MEDICAL SPACE FOR LEASE 1650 N WELLS ST CHICAGO, IL 60614 Wayne Caplan Senior Vice Michael Elam President Associate Advisor 312.529.5791 312.756.7331 [email protected] [email protected] SVN | CHICAGO COMMERCIAL | 940 WEST ADAMS STREET, SUITE 200, CHICAGO, IL 60607 LEASE BROCHURE Property Highlights PROPERTY SUMMARY PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Available SF: 2,000 - 6,910 SF • PRICE REDUCED - BEST DEAL ON OLD TOWN RETAIL SPACE • Perfect location for spas, medical / dental offices, apparel retailers, service providers, fitness users, and food users Lease Rate: $26.50 SF/YR (NNN) • 2,000 - 6,910 SF of retail / office space immediately available for lease Lot Size: 10,608 SF • Up to 69'-4" of frontage on Wells Street in Chicago's Old Town neighborhood • 2 spaces currently built-out as a former fitness tudios and an apparel store Building Size: 13,300 SF • Divisible to spaces as small as 2,000 SF • Tenant improvement allowance available for qualified enat nts Zoning: B3-5 • Just steps to Piper's Alley (featuring The Second City), Zanies Comedy Club, The Moody Church, Walgreens, Starbucks, Market: Chicago many other quality tenants • Easy access to CTA buses and trains (Brown and Purple lines), Lake Shore Drive, and Lincoln Park Zoo Submarket: Old Town / Lincoln Park • Surrounded by excellent demographics with high household incomes, high home values, and dense populations OLD TOWN RETAIL / OFFICE / MEDICAL SPACE FOR LEASE | 1650 N WELLS ST CHICAGO, IL 60614 SVN | Chicago Commercial | Page 2 The information presented here is deemed to be accurate, but it has not been independently verified. -

1449 S Michigan Ave CHICAGO, IL

1449 S Michigan Ave CHICAGO, IL PRICING AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS SOUTH LOOP OFFERING 8,033 SF OF RETAIL & OFFICE SPACE PROPERTY OVERVIEW: 1449 S Michigan Ave is 8,000+ square feet sitting on a 4,037 square foot parcel of land. 25 feet of Michigan Ave frontage with storefront space on the first floor and office space on the second floor. Michigan Avenue gets 19,400 vehicles per day. The façade is brand new with large windows providing plenty of natural light. The 2nd floor space has skylights that give the space character and beautiful lighting. The first floor retail space is leased and we are currently marketing the 2nd floor space with heavy interest. Located in the South Loop, this building is a short distance from McCormick Place, Wintrust Arena, and Marriott Marquis Hotel. It is also just two blocks from the Cermak Green Line L Station. A $390M expansion project to grow the nearby area is underway to create McCormick Square: a destination for new nightlife, hotels, and retail attractions. One of the primary highlights of the property is the rapidly growing community. Thanks to the properties proximity to the central business district, top parks, cultural attractions and schools, Chicago's South Loop has started to become one of the hottest markets for newer construction. Some of the newer developments include eight high-rise apartment buildings, two hotel expansions, office buildings and DePaul's Wintrust Arena. All of these new developments will provide additional exposure to the property but it will also create a more vibrant community. Much of its eastern edge is encompassed by the Museum Campus, an impressive collection of cultural treasures that includes the Field Museum, Adler Planetarium and Shedd Aquarium. -

MINUTES of the MEETING COMMISSION on CHICAGO LANDMARKS June 1, 2017

MINUTES OF THE MEETING COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS June 1, 2017 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks held its regularly scheduled meeting on June 1, 2017. The meeting was held at City Hall, 121 North LaSalle Street, Room 201-A, Chicago, Illinois. The meeting began at 12:49 p.m. PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Rafael Leon, Chairman Jim Houlihan, Vice Chairman David Reifman, Secretary, Commissioner of the Department of Planning and Development Gabriel Dziekiewicz Juan Moreno Ernest Wong ABSENT: Carmen Rossi Mary Ann Smith Richard Tolliver ALSO PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Dijana Cuvalo, Architect IV, Department of Planning and Development Lisa Misher, Department of Law, Real Estate Division Members of the Public (The list of those in attendance is on file at the Commission office.) A recording of this meeting is on file at the Department of Planning and Development/Planning, Design and Historic Preservation Division offices and is part of the public record of the regular meeting of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. Chairman Leon called the meeting to order. 1. Approval of the Minutes of Previous Meeting Regular Meeting of May 4, 2017 Motioned by Wong, seconded by Dziekiewicz. Approved unanimously (6-0). 2. Preliminary Landmark Recommendation QUINCY ELEVATED STATION WARD 42 220 South Wells Street Matt Crawford presented the report. Motion to adopt the preliminary landmark recommendation for the Quincy Elevated Station. Motioned by Moreno, seconded by Houlihan. Approved unanimously (6-0). 3. Citywide Adopt-a-Landmark Fund ADOPT-A-LANDMARK FUND Application and Funding Priorities Dijana Cuvalo presented the report. Motion to adopt the Adopt-a-Landmark Application and Funding Priorities Motioned by Wong, seconded by Dziekiewicz. -

Permit Review Committee Report

MINUTES OF THE MEETING COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS December 3, 2009 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks held a regular meeting on December 3, 2009. The meeting was held at City Hall, 121 N. LaSalle St., Room 201-A, Chicago, Illinois. The meeting began at 12:55 p.m. PRESENT: David Mosena, Chairman John Baird, Secretary Yvette Le Grand Christopher Reed Patricia A. Scudiero, Commissioner Department of Zoning and Planning Ben Weese ABSENT: Phyllis Ellin Chris Raguso Edward Torrez Ernest Wong ALSO PRESENT: Brian Goeken, Deputy Commissioner, Department of Zoning and Planning, Historic Preservation Division Patricia Moser, Senior Counsel, Department of Law Members of the Public (The list of those in attendance is on file at the Commission office.) A tape recording of this meeting is on file at the Department of Zoning and Planning, Historic Preservation Division offices, and is part of the permanent public record of the regular meeting of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. Chairman Mosena called the meeting to order. 1. Approval of the Minutes of the November 5, 2009, Regular Meeting Motioned by Baird, seconded by Weese. Approved unanimously. (6-0) 2. Preliminary Landmark Recommendation UNION PARK HOTEL WARD 27 1519 W. Warren Boulevard Resolution to recommend preliminary landmark designation for the UNION PARK HOTEL and to initiate the consideration process for possible designation of the building as a Chicago Landmark. The support of Ald. Walter Burnett (27th Ward), within whose ward the building is located, was noted for the record. Motioned by Reed, seconded by Weese. Approved unanimously. (6-0) 3. Report from a Public Hearing and Final Landmark Recommendation to City Council CHICAGO BLACK RENAISSANCE LITERARY MOVEMENT Lorraine Hansberry House WARD 20 6140 S. -

LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014

THE LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014 Mayor Rahm Emanuel City Hall - 121 N LaSalle St. Chicago, IL 60602 Dear Mayor Emanuel, As co-chairs of the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum Site Selection Task Force, we are delighted to provide you with our report and recommendation for a site for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. The response from Chicagoans to this opportunity has been tremendous. After considering more than 50 sites, discussing comments from our public forum and website, reviewing input from more than 300 students, and examining data from myriad sources, we are thrilled to recommend a site we believe not only meets the criteria you set out but also goes beyond to position the Museum as a new jewel in Chicago’s crown of iconic sites. Our recommendation offers to transform existing parking lots into a place where students, families, residents, and visitors from around our region and across the globe can learn together, enjoy nature, and be inspired. Speaking for all Task Force members, we were both honored to be asked to serve on this Task Force and a bit awed by your charge to us. The vision set forth by George Lucas is bold, and the stakes for Chicago are equally high. Chicago has a unique combination of attributes that sets it apart from other cities—a history of cultural vitality and groundbreaking arts, a tradition of achieving goals that once seemed impossible, a legacy of coming together around grand opportunities, and not least of all, a setting unrivaled in its natural and man-made beauty. -

Presence Saint Joseph Hospital in Partnership with Our Community

Presence Saint Joseph Hospital in Partnership with our Community Community Health Needs Assessment Report 2013 Presence Saint Joseph Hospital 2900 N. Lake Shore Drive Chicago, IL 60657 Table of Contents Ministry Overview ............................................................................................................................ 1 Target Areas and Populations ........................................................................................................ 2 CHNA Steering Committee ............................................................................................................. 3 CHNA Process ............................................................................................................................... 5 Mission, Vision and Values ............................................................................................................. 6 Community Health Profile Summary ............................................................................................... 7 Community Input Summary ............................................................................................................ 9 Community Asset Analysis ............................................................................................................. 11 Prioritized Health Needs ................................................................................................................. 12 Action Teams ................................................................................................................................. -

Pandemic Restrictions Cause 10-Year Peak in Office Vacancy

Research & Forecast Report DOWNTOWN CHICAGO | OFFICE Fourth Quarter 2020 Pandemic Restrictions Cause 10-Year Peak in Office Vacancy Sandy McDonald Senior Director of Research | Chicago As of January 6th, 2021, the Chicago Metro occupancy (according to Market Indicators Kastle Systems) was 16.9%, up 4.9% from 11.9% at the end of 2020. CHICAGO CBD OFFICE Q4 2020 Q3 2020 Q4 2019 Rents continue to tick down as availability ticks up with tenants across all classes contracting space and/or adapting new working environments VACANCY RATE 15.0% 13.8% 12.3% for their employees. Overall activity in the market was slow for a third AVAILABILITY RATE 20.8% 19.3% 16.0% consecutive quarter, as vacancies reach 2010 post-recession levels. QUARTERLY NET ABSORPTION (SF) (1,129,559) 236,973 408,517 Vacancy & Absorption YTD NET ABSORPTION (SF) (1,275,593) (146,034) 1,597,365 » In the fourth quarter of 2020, Chicago saw overall and sublease RENTAL RATES (PSF) $41.91 $42.13 $42.95 vacancy rates rise to the highest levels since the 2009 recession. The overall Chicago CBD vacancy rate increased 120 basis points to SUBLEASE VACANCY (SF) 2,770,321 1,935,838 1,429,706 15 percent with sublease vacancy accounting for 1.8 percent of this SUBLEASE AVAILABLE (SF) 5,866,761 4,770,502 2,936,278 total. UNDER CONSTRUCTION (SF) 4,631,081 6,473,843 5,475,409 » As expected, net absorption hit a low point in the final quarter, NEW SUPPLY (SF) 2,384,402 0 2,500,000 totaling 1.13 million square feet of negative net absorption bringing the 2020 total to 1.28 million square feet—both of which are the highest negative net absorption levels since 2009. -

Chicago’S “Motor Row” District 2328 South Michigan Ave., Chicago, Il 60616

FOR SALE 30,415 SF LAND SITE CHICAGO’S “MOTOR ROW” DISTRICT 2328 SOUTH MICHIGAN AVE., CHICAGO, IL 60616 WILLIS TOWER JOHN HANCOCK CHICAGO LOOP MARRIOTT MARQUIS HOTEL SOLDIER FIELD MCHUGH HOTEL WINTRUST ARENA HYATT REGENCY CERMACK CTA STATION SUBJECT SITE MICHIGAN AVENUE CTA ENTRANCE MCCORMICK PLACE I-55 JAMESON COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE MARK JONES, CCIM Senior VP, Investment Sales 425 W. North Ave | Chicago, IL 60610 (O) 312.335.3229 [email protected] www.jamesoncommercial.com ©Jameson Real Estate LLC. All information provided herein is from sources deemed reliable. No representation is made as to the accuracy thereof & it is submitted subject to errors, omissions, changes, prior sale or lease, or withdrawal without notice. Projections, opinions, assumptions & estimates are presented as examples only & may not represent actual performance. Consult tax & legal advisors to perform your own investigation. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PRICE REDUCED: $6,750,000 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Jameson Commercial is pleased to bring to market this 30,415 SF land site. The property is located in Chicago’s South Loop on South Michigan Avenue in the historic “Motor PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Row District” conveniently located adjacent to McCormick Place and just a 4-minute walk to the new CTA Greenline station. Although located in a historic district, the • Land Size: 30,415 SF site is one of the few unencumbered with historic landmark designation. A radical • Michigan Ave. Frontage: 170 FT transformation of the area is occurring with a number of significant new developments • Depth: 179 FT underway to transform the surrounding neighborhood into a vibrant entertainment • Zoning: DS-5 district. -

Sexual Harassment in the Workplace Training, Mar 2018

2018 Annual Report Acknowledgements Executive committee • President, Tim Egan, Resident • Vice President, Mary • Chairman, Giulia Sindler, Quincannon, @Properties Kamehachi • Secretary, Amy Lemar, • 1st Vice President, Christopher Wintrust Bank Old Town Donovan, House of Glunz • Treasurer, Vacant board of directors board of trustees • Lori Allen, Resident • Alderman Walter Burnett, 27th Ward • Alderman Brian Hopkins, 2nd Ward • James Dattalo, The Fudge Pot • Jesse White, Secretary of State • Michael Endrizzi, Wells on Wells • Sen. John Cullerton, IL Sen-6th • Don Goldstein, Wells • Rep. Sara Feigenholtz, IL House-12 Street Apartments • David Dattalo, The Fudge Pot • Bert Haas, Zanies • Patty Erd, The Spice House • Chad Novak, The Fireplace Inn • Tom Erd, The Spice House • Patrick Shaughnessy, Ninja • Kirsten Fitzgerald, A Red Orchid Theater Trader • Harry Huzenis, Jameson Commercial • Mike Bigane, 80 Proof Real Estate • Caitlin O’Brien, • Belle Kerman, Kermen Enterprises MADO Management • Dino Lubbat, Dinotto’s Pizza e Vino • Agnese Milito, Orso’s Italian Restaurant • Gretchen Reachmack, Resident • Frank Milito, Orso’s Italian Restaurant • Margaret Comer, Resident • Kurt Jones, Franklin Fine Arts Center • Sara Plocker, Sara Jane • Richard Novak, The Fireplace Inn • Jennifer Tremblay, O’Briens • Peter O’Brien, MADO Management Restaurant • Mimi O’Brien, Resident • Scott Wilhelm, Byline Bank • Meghan O’Brien, Resident • Stanley Paul, Resident • Frank Reda, Topo Gigio • David Zimmer, Fleet Feet Chicago • Robert Block. Resident • Courtney Kennedy, Resident • Brad Bohlen, Plum Market • Tim Ryll, Four Corners • Ryan Marks, The Vig • Peter Lardakis, Kanela Breakfast Club • Tony Tomaska, Navigant • Brinton Coxe, Handle With Care Staff Executive Director Marketing & Membership Coordinator Ian M. Tobin Sam Waldorf 1 2018 Annual Report letter from the president In 2018, the Old Town neighborhood made great progress. -

Minutes of the Meeting Commission on Chicago Landmarks October 4, 2012

MINUTES OF THE MEETING COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS OCTOBER 4, 2012 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks held a regular meeting on October 4, 2012. The meeting was held at City Hall, 121 N. LaSalle St., City Hall Room 201-A, Chicago, Illinois. The meeting began at 12:50 p.m. PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Rafael Leon, Chairman John Baird, Secretary Tony Hu James Houlihan (arrived after item 1) Ernest Wong Anita Blanchard Christopher Reed Mary Ann Smith Andrew Mooney, Commissioner of the Department of Housing and Economic Development ALSO PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Eleanor Gorski, Assistant Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development, Historic Preservation Division Arthur Dolinsky, Department of Law, Real Estate Division Members of the Public (The list of those in attendance is on file at the Commission office.) A tape recording of this meeting is on file at the Department of Housing and Economic Development, Historic Preservation Division offices and is part of the permanent public record of the regular meeting of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. Chairman Leon called the meeting to order. 1. Approval of the Minutes of the September 6, 2012, Regular Meeting Motioned by Smith, seconded by Wong. Approved unanimously. (8-0) Commission member Jim Houlihan arrived. 2. Final Landmark Recommendation to City Council MARTIN SCHNITZIUS COTTAGE WARD 43 1925 N. Fremont Street Resolution to adopt the Final Landmark Recommendation to City Council that the MARTIN SCHNITZIUS COTTAGE be designated as a Chicago Landmark. Alderman Michelle Smith, (43rd Ward), within whose ward the building is located, expressed support for the designation. Michael Spock on behalf of the Barbara Spock Trust, the property owner, also expressed support for the landmark designation. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................