Essays on Racial Ingroup Bias in Political Judgments Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center for the Study of Democracy

Cent er f or t he St udy of Democr acy Organized Research Unit ( ORU) Universit y of Calif ornia, Irvine Fall 2004 CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF DEMOCRACY In 2004, more than 60 nations around the world are holding elections. Nearly 2 billion people-- including Americans--will trek to the polls to select their government and make their views known to their political leaders. This marks a dramatic change in recent history. Until very recently the total number of people living in democracies was far smaller than just the number voting in 2004. In the last two decades, citizens from Afghanistan to Indonesia to the states of the former Soviet Empire have embraced democracy. The recent World Values Survey suggests that democratic aspirations exist on Sen. Edward M. Kennedy Delivers the nearly a global scale as a common human value. Peltason Lecture Yet, the existence of fair and free elections remains a challenge in many nations. Senator Edward M. Kennedy has been described as one And electoral democracy is just the beginning-- of the most influential legislators in American history. real democracy requires much more. Even in the He delivered the annual Peltason Lecture at UC established democracies, substantial democratic Irvine, discussing the challenges of health policy and challenges remain. economic security facing the nation to an overflow The Center for the Study of Democracy audience of more than a thousand people. is one of the largest and oldest academic centers Kennedy spoke about Americans need for health in America that focuses on the development of care, and the special problems this poses for senior democracy. -

Have You S Logged Onto S Apsanet Lately?

versity (contact: David Walsh); Encouraging the Brightest: Howard Community College (con- The 2000 Ralph Bunche tact: Zoe Irvin); Marymount Univer- Summer Institute sity (contact: Chris Synder) Have you Karen Cox, University of Virginia University of Illinois, Chicago s logged onto Twenty gifted undergraduate stu- Departmental Representatives dents of color from colleges across Dick Simpson (Project Contact), S APSANet the country attended the 14th an- Cheryl Brandt, Rasma Karklins, nual Ralph Bunche Summer Insti- Betty O'Shaughnessy, Barry 3 Lately? tute at the University of Virginia Rundquist this summer in order to learn more about graduate study in political sci- 0, The summer months Partnering Institutions ence. Sponsored jointly by the Na- "O may be quiet around Chicago State University (contact: tional Science Foundation, the De- Phillip Beverly); City Colleges of 0) campus, but we have partment of Government and Chicago (contact: Constance A. •* been busy adding new Foreign Affairs at the University of Mixon); University of Illinois, f* material for teachers and Virginia, and the American Political Springfield (contact: Steve Schwark); O students. Jump to any of Science Association, the Bunche In- stitute is designed to introduce stu- Joliet Junior College (contact: Rob- orq these new sites: ert E. Sterling) dents of color to graduate school • and to encourage their application to Indiana University Service Learning Ph.D. programs in political science. This year's class represented schools Departmental Representatives What is service learning? How can you implement SL as diverse as UCLA, St. Mary's Uni- Norm Furniss (Project Contact), versity (TX), the University of Vir- Robert Huckfeldt, Marjorie Her- programs in your depart- ment. -

The Political Representation of Blacks in Congress: Does Race Matter? Author(S): Katherine Tate Source: Legislative Studies Quarterly, Vol

The Political Representation of Blacks in Congress: Does Race Matter? Author(s): Katherine Tate Source: Legislative Studies Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Nov., 2001), pp. 623-638 Published by: Comparative Legislative Research Center Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/440272 Accessed: 12/11/2009 19:50 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=clrc. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Legislative Research Center is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Legislative Studies Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org KATHERINETATE Universityof California-Irvine The PoliticalRepresentation of Blacks in Congress: Does Race Matter? Congressional scholars generally take the position that members of Congress don't have to descriptively mirrortheir constituents in order to be responsive. -

'For Better and for Worse?': Black Opinion on the U.S. Supreme Court

‘For Better and For Worse?’: Black Opinion on the U.S. Supreme Court Since Brown Rosalee A. Clawson1, Katherine Tate2, and Eric N. Waltenburg1 Purdue University1 University of California, Irvine2 Note: This paper was prepared for delivery at the research workshop entitled, “America’s Second Revolution: The Path to – and from – Brown v. Board of Education,” held at the University of Memphis’s Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change, March 12-14, 2004. The authors’ names are presented in alphabetical order. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support that they received from the Law and Social Sciences Program of the National Science Foundation (#SES-0331509). Rosalee Clawson and Eric Waltenburg also wish to acknowledge the support that they received for this project from their academic institution, Purdue University, while Katherine Tate acknowledges the support she has received for this study from the Center for the Study of Democracy at UC Irvine. Comments and suggestions can be directed to Rosalee Clawson via email at [email protected]. 2 As the third branch of the federal government, the Supreme Court is frequently characterized as the defender of minority rights over majority power. Yet, this has not always been the case in the arena of racial politics. Indeed, throughout much of its history, the Supreme Court has protected the rights of the White majority against the claims for legal and political equality of Blacks. For example, in the Civil Rights Cases1 of 1883, the Court undercut and effectively reversed the efforts of the Reconstruction Congress to ensure that Blacks would enjoy their full and equal rights as promised them by the Fourteenth Amendment. -

Katherine Tate

Katherine Tate Department of Political Science Brown University Box 1844 111 Thayer Street Providence, RI 02912 E-mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D. University of Michigan, Political Science, 1989. M.A. University of Michigan, Political Science, 1985. B.A. University of Chicago, Political Science with Honors, 1983. Research and Teaching Fields: African American politics, Race, ethnicity and gender in political science, American public opinion, government, and urban politics Academic Positions: Professor, Department of Political Science, Brown University, 2013-date. Professor, Department of Political Science, University of California, Irvine, 2001-2013. Affiliated Faculty Member, UC Irvine’s African American Studies Program, 2002-2013. Affiliated Faculty Member, UC Irvine’s Center for the Study of Democracy, 1997-2013. Chair, Department of Political Science, University of California Irvine, 2002-2004. Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of California, Irvine, 1997-2001. Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Ohio State University, 1993-1997. Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford, California, 1995-1996. Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1992-1993. Visiting Research Associate (Chancellor's Distinguished Professorship), Survey Research Center, University of California at Berkeley, July 1991-June 1992. Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1989-1992 (On presidential leave 1991-1992). 2 Research Associate, The W.E.B. DuBois Institute, Harvard University, Fall 1988. Books: Katherine Tate, James Lance Taylor, and Mark Q. Sawyer, Eds. 2014. Something’s In the Air: Race and the Legalization of Marijuana. New York, NY: Routledge. Katherine Tate. 2014. Concordance: Black Lawmaking in the U.S. Congress from Carter to Obama. -

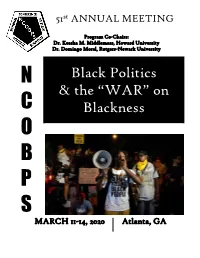

NCOBPS 2020 Program

st 51 ANNUAL MEETING Program Co-Chairs: Dr. Keesha M. Middlemass, Howard University Dr. Domingo Morel, Rutgers-Newark University N Black Politics & the “WAR” on C Blackness O B P S MARCH 11-14, 2020 Atlanta, GA BLACK POLITICS AND THE “WAR” ON BLACKNESS In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “War on Poverty,” and nearly 50 years have passed since President Nixon declared a “War on Drugs.” What are the implications of these “wars” on Black citizens, Black communities, Black bodies, and Black politics? The conference theme, Black Politics and the “War” on Blackness, examines how the study of Black politics can assess the intended and unintended effects of “war” on contemporary issues, such as policing, criminal justice, healthcare, international relations, comparative politics, and more. The word “war” has been used to problematize social problems and also indicates the power of the state to disapprove and reject “others.” War is also a powerful symbol that represents aggressive competition, armed combat, international hostilities, and rivalry between two opposing sides that are in conflict over a set of values, morals, principles or tenets. Punitive policies are allowed to flourish as society uses the word “war” as a metaphor that has allowed the government to unleash its resources to defeat the “enemy;” in many instances the explicit enemy is Blackness, Black bodies, Black politics, and Black experiences. As a result, “war” is a policy decision that spawns a number of related laws, strategies, and rules to harness and control Black bodies. This call for papers, roundtables, and other submissions provides the context for the 51st Annual Meeting of the National Conference of Black Politics. -

Belinda Robnett

1 BELINDA ROBNETT OFFICE: HOME: Department of Sociology 19 Twain University of California, Irvine Irvine, Calif. 92617 Irvine, Calif. 92697-5100 (949) 856-0506 (949) 824-1648; Fax: (949) 824-4717 Citizenship: U.S.A. EDUCATION: Ph.D. 1991, Sociology, University of Michigan M.A. 1987, Sociology, University of Michigan M.A. 1985, Psychology (Social Psychology), Princeton University Ed.M. 1982, Education (International Development), Harvard University A.B. 1978, Psychology, Stanford University FACULTY POSITIONS: University of California, Irvine, Department of Sociology Full Professor University of California, Irvine, African American Studies Program Director, 2000-2002 University of California, Davis, Department of Sociology And Women’s Studies Associate Professor, 1998-1999 Assistant Professor, 1990-1997 PUBLICATIONS: Books: Robnett, Belinda and Katherine Tate. In Progress. Gender Pluralism. Robnett, Belinda. In Progress. Surviving Success: Black Political Organizations and the Politics of Post-Racial Illusions. Meyer, David, Nancy Whittier, and Belinda Robnett, editors. 2002. Social Movements: Identity, Culture, and the State. Oxford University Press. Robnett, Belinda. 1997. How Long? How Long?: African American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights. Oxford University Press. 2 Articles: Rafalow, Matthew, Cynthia Feliciano and Belinda Robnett. Under Review. “Racialized Femininity and Masculinity in the Preferences of Lesbian and Gay Male Daters”. Robnett, Belinda, Carol Glasser and Rebecca Trammell. In Press. “Waves of Contention: Relations among the Radical, Moderate, and Conservative Movement Organizations”, Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change, Vol. 38. Bany, James, Belinda Robnett and Cynthia Feliciano. 2014. "Gendered Black Exclusion: The Persistence of Racial Stereotypes among Daters" James Bany, Belinda Robnett and Cynthia Feliciano, Race and Social Problems, Vol. -

Seminar on Race and American Politics

PLSC 597-004: Seminar on Race and American Politics Ray Block Jr. Fall Semester, 2020 E-mail: [email protected] Web: https://polisci.la.psu.edu/people/ray-block Office Hours: T/Th 10:00AM -11:45AM Class Hours: M 9:00AM - 12:00PM Office: 308 Pond Laboratory Class Room: Not applicable (we meet via Zoom) Course Description Politics is about “who gets what, when, [where], and how” (Lasswell 1951). In this course, we will consider the role of race in who gets what, when, where, and how. We will begin by surveying the historical contexts of racial politics in the United States. In so doing, we will acknowledge that race can be (and often is) political. From this foundation, we will examine the various controversies that surround the role of race in American society and politics. These controversies, or “issues,” affect public opinion, political institutions, political behavior, and salient public policy debates. Although focusing principally on matters relating to African Americans, where possible and appropriate, we will also make comparisons with other racial/ethnic groups. Learning Objectives Overall, I want students to appreciate that American politics fundamentally doesn’t make sense without explicitly considering race. As students will see below, there are several broad themes guiding this course. Mainly, we will explore what race is, why it matters, and how it shapes attitudes, behaviors, policies, and institutions. My goals for the course include, but are not limited to, helping students cultivate: 1. a strong substantive understanding of how race influences (and is shaped by) the American political system; 2. -

2006 Commencement

2006 Commencement MAY 22, 2006, 8:30 A.M. COLORADO COLLEGE ALMA MATER (O Colorado College Fair) Words and music written in 1953 by Charles Hawley ’54 and Professors Earl Juhas and Albert Seay O Colorado College fair, O Colorado College fair, We sing our praise to you; Long may your fame be known; Eternal as the Rockies, May fortune smile upon you, that form our western view; and honor be your own; Your loyal sons and daughters Our Alma Mater always, will always grateful be; Your loyal children we; The college dear to all of our hearts Together let us face the future, is our C.C. Hail C.C. AMERICA, THE BEAUTIFUL (O Beautiful for Spacious Skies) Music written by Samuel A. Ward (1847–1903) Words written by Katherine Lee Bates (1859–1929) (Selected Verses) O beautiful for spacious skies, O beautiful for pilgrim feet For amber waves of grain, Whose stern impassioned stress For purple mountain majesties A thoroughfare for freedom beat Above the fruited plain. Across the wilderness. America! America! America! America! God shed His grace on thee, God mend thine every flaw, And crown thy good with brotherhood Confirm thy soul in self-control, From sea to shining sea. Thy liberty in law. THE COLORADO COLLEGE • 125th ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT • MAY 22, 2006, 8:30 A.M. PROGRAM Presiding: Richard F. Celeste, President of Colorado College • • • *PROCESSIONAL Entrada . G. F. Handel (1685–1759) Voluntary on Old 100th . Henry Purcell (c. 1659–1695) Fanfare . Dietrich Buxtehude (1637–1707) Trumpet Voluntary . Henry Purcell Brass Ensemble Donald P. Jenkins, Professor Emeritus of Music, Conductor • • • *INVOCATION Bruce Coriell, Chaplain • • • *COLORADO COLLEGE ALMA MATER “O Colorado College Fair” .