The Role of Trust in Administering the Incomes Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hellozagreb5.Pdf

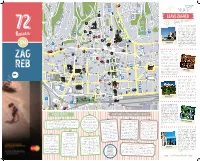

v ro e H s B o Šilobodov a u r a b a v h Put o h a r r t n e e o i k ć k v T T c e c a i a i c k Kozarčeve k Dvor. v v W W a a a Srebrnjak e l Stube l St. ć č Krležin Gvozd č i i s ć Gajdekova e k Vinogradska Ilirski e Vinkovićeva a v Č M j trg M l a a a Zamen. v č o e Kozarčeva ć k G stube o Zelengaj NovaVes m Vončinina v Zajčeva Weberova a Dubravkin Put r ić M e V v Mikloušić. Degen. Iv i B a Hercegovačka e k Istarska Zv k u ab on ov st. l on ar . ić iće Višnjica . e va v Šalata a Kuhačeva Franje Dursta Vladimira Nazora Kožarska Opatička Petrova ulica Novakova Demetrova Voćarska Višnjičke Ribnjak Voćarsko Domjanićeva stube naselje Voćarska Kaptol M. Slavenske Lobmay. Ivana Kukuljevića Zamenhoova Mletač. Radićeva T The closest and most charming Radnički Dol Posil. stube k v Kosirnikova a escape from Zagreb’s cityŠrapčeva noise e Jadranska stube Tuškanac l ć Tuškanac Opatovina č i i is Samobor - most joyful during v ć e e Bučarova Jurkovićeva J. Galjufa j j Markov v the famous Samobor Carnival i i BUS r r trg a Ivana Gorana Kovačića Visoka d d andJ. Gotovca widely known for the cream Bosanska Kamenita n n Buntićeva Matoševa A A Park cake called kremšnita. Maybe Jezuitski P Pantovčak Ribnjak Kamaufova you will have to wait in line to a trg v Streljačka Petrova ulica get it - many people arrive on l Vončinina i Jorgov. -

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

CRAFT BREWERY Cheers! = Zheev-Yell-Ee! Imagine

FOOD&DRINK THINGS2DO THINGS2SEE HOTELS&HOSTELS 1 Kaptol 12 1 1 Zagrebački neboder 1 RESTAURANT CONTE KARTING ARENA +385 1 778 75 34 Zagreb 360° HOTEL GALLUS 01/4899254, 099 3039111 Ilica 1a Brestovečka cesta 2, Sesvete, -10% www.karting-arena.com Zagreb Eye viewpoint th -10% www.restaurant-conte.hr 16 floor 01/2027 147 Zagrebački Velesajam, Entrance east 3 [email protected] WITH COUPON The viewpoint and the bar are located at the Jelačić WITH COUPON Rooms at hotel Gallus are newly renovated with Did you know that Zagreb has the largest indoor square, Ilica 1a, on the 16th floor - on top of Zagreb's Next to the Cathedral, in the city center, restaurant elegant furnishing and functional desk, an integrated karting track in this part of Europe? Karting Arena skyscraper. The viewpoint provides a unique view on the Conte offers high-quality fish specialties and up-to- flat–screen TV and free parking, safebox, elegant Zagreb is the biggest professional go-kart track in the main square, Cathedral, Upper and Lower Town and other date preparation and service. You can also eat some bathrooms with cosmetic accessories. All rooms have region. Feel like a profesional F1 driver !!! most important cultural and historical architectures of of our exquisite meat dishes. The restaurant has a smoke detectors and emergency system. A bar and “Best rated attraction in Zagreb - Lifetime experience” Zagreb, its squares, streets and parks. It is open 365 days parking area, and it is also suitable for groups. restaurant is at guests disposal at Gallus Hotel and all /// only 1 km from city center /// per year from 10am to 12pm. -

Glasnik 09-2016

Godina: XXV Datum: 02. 03. 2016. Broj: 09 SADRŽAJ - Registracije Izdaje: Hrvatski nogometni savez Telefon: +385 1 2361 555 Ulica grada Vukovara 269 A, HR-10000 Zagreb Fax: +385 1 2441 500 Uređuje: Ured HNS-a IBAN: HR25 2340009-1100187844 (PBZ) Odgovorni urednik: Vladimir Iveta 2 R E G I S T R A C I J E Brisanje iz registra Brisu se igraci iz registra Štignjedec Josip "Zagreb" Zagreb, Rupčić ZAGREBAČKO PODRUČJE Darijan "Jarun" Zagreb, Grebenar Bruno "Sesvetski Kraljevec" Sesvetski Kraljevec, Sekulić Ivan "Lučko" Lučko, Kovačić Miro ZAGREBAČKI NOGOMETNI SAVEZ "Hrvatski Dragovoljac" Zagreb, Ćorić Drago "Dubrava Tim kabel" Zagreb, (Sjednica 23.02.2016) Živković Ivan "Trnje" Zagreb jer odlaze na područje drugog saveza. Brisanje iz registra (Sjednica 25.02.2016) Brisu se igraci iz registra Tomičić Brisanje iz registra Vlado "Ivanja Reka" Ivanja Reka jer odlaze na područje drugog saveza. Brisu se igraci iz registra Matleković Juraj "Ponikve" Zagreb, Majstorović (Sjednica 24.02.2016) Antonio "Ivanja Reka" Ivanja Reka, Abramović Matej "HAŠK" Zagreb, NK "RUDEŠ" ZAGREB: Ivanko Patrik "Ivanja Reka" Ivanja trener Bišćan Igor (Seniori - Reka jer odlaze na područje drugog pomoćni) saveza. NK "MAKSIMIR" ZAGREB: (Sjednica 26.02.2016) trener Vidović Rajko (Seniori) NK "LOKOMOTIVA" ZAGREB: Džalto NK "DUBRAVA TIM KABEL" Marko (Sesvete Sesvete), Kordej ZAGREB: Jura (Olimp Zaprešić), Čl. 37/8 trener Matić Davor (Seniori) ŽNK "AGRAM" ZAGREB: Andrijanić Raskidi ugovora Laura , Čl. 37/8 Graberski Ana , Čl. 37/1 NK "GNK DINAMO" ZAGREB i igrač Kotarski Dominik sporazumno NK "HAŠK" ZAGREB: Waite Nicholas raskinuli stipendijski ugovor broj 65 Lawson , Čl. 16-37/1 od 04.02.2015. -

ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING D.O.O.- Podružnica Čistoća PLAN REDOVNOG ODVOZA GLOMAZNOG OTPADA IZ DOMAĆINSTAVA ZA 2013

ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING d.o.o.- Podružnica Čistoća PLAN REDOVNOG ODVOZA GLOMAZNOG OTPADA IZ DOMAĆINSTAVA ZA 2013. GODINU RED. NAZIV PODRUČJA RADA GRADSKA ČETVRT 2013. 2013. BR. 1. SAVSKI KUTI 18.2. 18.7. Donji grad 2. VESLAČKO NASELJE 18.2. 18.7. Donji grad 3. CVJETNO NASELJE 18.2. 18.7. Donji grad 4. CVJETNICA 19.2. 19.7. Donji grad 5. VRBIK( POLJANE) 19.2. 19.7. Donji grad 6. MIRAMARE 19.2. 19.7. Donji grad 7. MARTINOVKA 19.2. 19.7. Donji grad 8. KANAL 20.2. 20.7. Donji grad 9. MARIN DRŽIĆ 20.2. 20.7. Donji grad 10. TRNJANSKA SAVICA 20.2. 20.7. Donji grad 11. TRNJE 21.2. 22.7. Donji grad 12. STARO TRNJE 21.2. 22.7. Donji grad 13. SIGEČICA 22.2. 23.7. Donji grad 14. FOLNEGOVIĆEVO NASELJE 22.2. 23.7. Peščenica 15. HRV.KNJIŽ. M.BUDAKA 22.2. 23.7. Peščenica 16. SAVICA ŠANCI 23.2. 24.7. Peščenica 17. FERENŠČICA 23.2. 24.7. Peščenica 18. VOLOVČICA 25.2. 25.7. Peščenica 19. BRUNO BUŠIĆ 25.2. 25.7. Peščenica 20. DONJE SVETICE 26.2. 26.7. Peščenica 21. PEŠČENICA 26.2. 26.7. Peščenica 22. BORONGAJ LUGOVI 27.2. 27.7. Peščenica 23. VUKOMEREC 27.2. 27.7. Peščenica 24. KOZARI BOK 28.2. 29.7. Peščenica 25. KOZARI PUTEVI 28.2. 29.7. Peščenica 26. PETRUŠEVEC 1.3. 30.7. Peščenica 27. ŽITNJAK 1.3. 30.7. Peščenica 28. IVANJA REKA 2.3. 31.7. Peščenica 29. RESNIK 2.3. 31.7. Peščenica 30. -

Zagrebačke Teme

zagrebačke teme Prethodno priopćenje UDK 801.311 : 940.1 Zagreb (497.5) Primljeno 2018-06-08 Prihvaćeno za tisak 2018-08-29 KRATKI UVOD U KASNOSREDNJOVJEKOVNU ZAGREBAČKU TOPONIMIJU1 Branimir Brgles, Zagreb Sažetak Autor analizira najstarije pisane potvrde zagrebačkih toponima. Riječ je o potvrdama koje nalazimo u vrelima iz XII. i XIII. stoljeća. Detaljnije je analizirana toponimija i topo- grafija užeg prostora staroga Gradeca i Kaptola. Analizirane su najstarije potvrde hodonima i toponima te njihove poveznice s topografijom srednjovjekovnoga urbanog prostora. Potom su analizirane neke od najstarijih povijesnih toponimijskih potvrda iz šire zagrebačke oko- lice, odnosno iz prostora između Medvednice i rijeke Save. Tekst daje kratak pregled vrela, povijesnih potvrda i suvremenih tumačenja najvažnijih zagrebačkih toponima. Na koncu je ponuđen zaključak, kojim su toponimijske potvrde povezane s povijesnim topografskim i okolišnim uvjetima. Nastojalo se povezati povijesne i okolišne procese u srednjem vijeku s motivacijama imenovanja toponima. Ključne riječi: hodonimi; Zagreb; srednjovjekovni i ranonovovjekovni hodonimi UVOD Najraniji zapisi zagrebačkih srednjovjekovnih i ranonovovjekovnih toponima svjedoče kako su se u orijentaciji urbanoga stanovništva najčešće upotrebljavala opisna imena. Slična je motivacija i pri takozvanoj onimizaciji, odnosno imeno- vanju pri kojemu su novonastali toponimi preuzeti od starijih topografskih ime- na. Za srednjovjekovne stanovnike najjednostavnije je bilo imenovati neki pro- stor prema obilježjima po -

Contacts: Msc Ksenija Keča, Head of International Office Libertas

2019./2020. Contacts: MSc Ksenija Keča, Head of International Office Libertas International University, [email protected] Martina Glavan, International Office Assistant, +385 1 56 33 151, [email protected] This brochure is the result of the professional project of the English language course for Tourism and Hospitality Management at the Libertas International University. Texts by: Doris Barić, student Daria Domitrović, student Nikolina Pavić, student Dina Gugo, student Hana Pehilj, student Adnan Kulenović, student Mia Štimac, student Nina Branković, student Kristijan Ivić, student Photo: Doris Barić, student Project coordinator: Martina Pokupec, M.Ed. Assistant project coordinator: Doris Barić, student Contributors: Ana Guberina, student Mihovil Žokvić, student Language revision: Mark Osbourne, Martina Pokupec, M.Ed. Review: Ksenija Keča, MSc Višnja Špiljak, PhD Publisher: Libertas International University, Trg J. F. Kennedy 6B, 10000 Zagreb Croatia Zagreb, Croatia This brochure has been designed for you by students of Tourism and Hotel Management at the Libertas International University to welcome you to the city of Zagreb. We wish to make your student life in Zagreb easier and exciting, so the students have selected some of their favorite places, which they would visit themselves if they wanted to relax, dine, try out our night life, study or experience some culture. In this brochure, you will not only read about museums and landmarks of significant historical and cultural heritage – it is even better! Here you can get their inside information on the best spots to hang out in the city and just enjoy yourself. We are very thrilled that the texts you will read and the photographs you will see have all been written and taken by the students themselves, that of course we wish you enjoy. -

Culture & Events

CULTURE & EVENTS 1 May 31 – July 5 Strossmartre Saunter up towards the outlet to display their talents and Ida Jakšić’s designs will Stross - Zagreb’s Strossmayer promenade and the old be featured in June. Museum of Arts and Crafts (B-3) Trg romantic Upper Town as spring kicks off yet another season of maršala Tita 10, tel. 488 21 11 this well known spectacle. Visitors can enjoy a feast of cultural June 1 – 31 Miniature Furniture from the Museum of events, entertainment, film, theatre and other programmes. Arts and Crafts Collection Throughout the 17th and 18th Strossmayer promenade (B-2) century, the production of furniture and the ornaments to June – July The Laganiši Cave - A place of life and death go with it was a growing trade. Objects that we classify as Step back in time as a display of results from the excavations being placed on large furniture are called ‘sopramobiles. They made at the Laganiši cave near the town of Oprtalj, which were are miniature in shape and require precision on the artist’s conducted from 2004 until 2007, will be presented. Traces of behalf. Every intricate detail is noted, some are decorated life from the early periods were found inside the cave, dating in bronze as to appear as precious jewels. Craftsmanship from the Stone Age (Neolithic), through to the Bronze Age and was of essence and they had to be perfectionists as can be Antique period. Archeological Museum in Zagreb (C-2) Trg seen here on display. Museum of Arts and Crafts (B-3), N. -

New Croatian Features & Shorts 02

Nova Ves 18 | 10000 Zagreb, hr [email protected] [email protected] | www.havc.hr meet & greet th 10 ANNIVERSARY OF In 2018, the 10th anniversary of establishing the Croatian CROATIAN AUDIOVISUAL Croatian Audiovisual Centre, the Croatian film Audiovisual Centre CENTRE scene is as alive and as vibrant as ever. Features, AT THE FILM both live-action and documentary, use modern In the past ten years, the Croatian audiovisual aesthetics to tackle a wide variety of urgent MARKET landscape has been restructured and reshaped. issues. Short films across all genres still inject see Pavilion no. 135 Most importantly, this was a decade in which the Croatian cinematic bloodstream with a gush Village International Riviera its authors and works started to travel, and of new ideas, while international co-productions their efforts were acknowledged by festival merge local and international talent to create Croatian Audiovisual Centre programmers, jury members and audience alike. stories that travel far beyond national borders. Department of Promotion Some of them were lucky enough to be screened [email protected] in the programmes of A-list festivals, some were With our hopes up and spirits high for the ten www.havc.hr even luckier to return from them with awards, years ahead of us, we present you with a fresh while others got the opportunity for distribution on crop of Croatian cinema, brimming with stories the international market, warming the hearts and and authors waiting to be discovered, discussed intriguing the minds of audiences across the globe. and enjoyed. Producers on the Move FILMS IN COMPETITION CROATIAN SHORTS AT Oliver Sertić, Restart THE SHORT FILM CORNER Directors’ Fortnight After Party by Viktor Zahtila (pg. -

Zagreb ESSENTIAL Spring 2015 CITY G UIDES

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb ESSENTIAL Spring 2015 CITY G UIDES Pocket’s Progress With the mission of giving you ‘ten city changes since our first edition’ Zagreb Book Festival Follow IYPs official guide to the best book fest for every guest Divine Croatian Design Go local… Be local… Support local… N°79 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Contents ESSENTIAL CIT Y GUIDES Foreword 4 The editor’s choice on what not to miss this Spring Arrival & Getting Around 6 Lost? Help is at hand Pocket’s Progress 10 Ten big ways in which Zagreb has changed Culture & Events 12 You won’t be bored Croatian Design 24 Support the local designers Zagreb Pulse 28 Designer tips Kišobrani Cerovečki Archives Restaurants 30 The Kaplja Raincoat – This award winning hand-made Coffeeraincoat designed & Cakes by Ana Rimac, is full-circuit in cut 38 Enjoy the riches Treatand yourself made from a high quality cotton material that is Local Flavour 35 impregnated with a waterproof layer. The pattern is taken Nightlifefrom the Šestine Umbrella and is one of the latest gems 44 A taste of culture Whenfrom youthe Cerovečki just gotta Crafts boogie Shop! Coffee & Cakes 39 Sightseeing 45 Treat yourself Check out the highlights Nightlife 41 Shopping 52 When you just gotta boogie Perfect gifts and souvenirs Hotels 60 A place to rest your weary head List of small features Tasty Getaways 35 The foodie’s guide 38 Horrible Histories 50 More style for less cash 58 City Center Shopping 59 Maps & Index Street register 64 City map 65 City centre map 66-67 Take a peek at a few hand-picked eateries that are nestled around town and offer the very best in indigenous specialties made from local and seasonal ingredients and wines from central Croatia. -

Filming in Croatia 2014 Contents

Filming in Croatia Filming in Croatia 2014 Contents Introduction · 5 Regions · 68 Istria · 71 The Croatian Film Commission · 8 Kvarner and the Highlands · 75 Co-Production Funding · 13 Dalmatia · 81 Cash Rebate · 14 Slavonia · 89 Cultural Test · 17 Central Croatia · 95 Resources and Infrastructure · 22 Brief Overview of International Production know-how · 26 Productions in Croatia · 100 Production Companies · 27 Facilities and Technical Equipment · 29 Address Book · 114 Crews · 31 Production Companies · 117 Costumes & Props · 33 Post-Production, Service Locations · 35 and Rental Companies · 137 Hotels & Amenities · 37 Cinema Clubs and Art Associations · 146 Airports · 39 Distribution Companies · 148 Sea Transport · 41 State and Public Institutions · 151 Buses and Railways · 43 Professional Associations and Guilds · 152 Traffic and Roads · 45 Authors Societies and Rights Organizations · 154 Useful Info · 46 Institutions of Higher Education for Filming and Location Permits · 49 Professionals in Film, Television, Theatre Visas · 50 and Related Areas · 155 Working Permits for Foreign National Broadcasters · 156 Nationals · 51 Cinemas · 157 Customs Regulations · 53 Film Festivals · 160 Temporary Import of Film Publications · 162 Professional Equipment · 55 Facts about Croatia · 56 Basic info · 61 Basic Phrases · 65 Distances · 66 Poreč, Mladen Šćerbe, Courtesy of the Croatian Tourist Board Introduction Croatia may be a small country, but it has a remarkably vibrant film industry, with exceptional local talent and production companies that have -

Diplomski Rad

SVEUĈILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA POVIJEST DIPLOMSKI RAD MARTINA PONGRAC Zagreb, 2013. SVEUĈILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA POVIJEST ZAGREB U 19. STOLJEĆU: URBANISTIĈKI RAZVOJ I PROSTORNA ORGANIZACIJA Diplomski rad Studentica: Martina Pongrac Mentor: dr.sc. Zvjezdana Sikirić Assouline Zagreb, 2013. Sadržaj 1. Uvod 1 2. Osobitost prostora kao faktor razvoja Zagreba 3 3. Društveno politiĉke prilike u Zagrebu u 19. stoljeću 4 3.1. Zagreb od 1800. do 1850. godine 4 3.2. Zagreb od 1850. do 1914. godine 5 4. Demografske znaĉajke Zagreba u 19. stoljeću 7 5. Urbanistiĉki razvoj i prostorna organizacija 11 5.1. Fizionomske promjene Zagreba u 19. stoljeću 12 5.1.1. Širenje i urbanizacija grada 16 5.1.2. Zagrebaĉka periferija 33 5.1.3. Rješavanje komunalnih pitanja 34 5.2. Razvoj funkcija Zagreba u 19. stoljeću 38 5.2.1. Palaĉe, graĊanske kuće i perivoji 38 5.2.2. Obrtništvo, manufakture i poĉetak industrijalizacije 41 5.2.3. Prometno znaĉenje i trgovina 44 6. Zakljuĉak 47 7. Literatura 49 1. Uvod Tema kojom se bavim u svom diplomskom radu je Zagreb u 19. stoljeću, odnosno urbanistiĉki razvoj grada i njegova prostorna organizacija. Za obradu teme odluĉila sam se potaknuta zanimanjem za povijest rodnog grada, a posebno za razdoblje 19. stoljeća koje je iznimno znaĉajno u njegovoj dugoj prošlosti. Upravo u tom razdoblju postavljeni su temelji Zagreba kao jedinstvene teritorijalne cjeline i zapoĉinje njegova transformacija od srednjovjekovnog gradića, kakav je bio poĉetkom stoljeća, do urbanog središta i srednjoeuropskog modernog grada. Obradu teme zapoĉela sam s osnovnim informacijama o prostoru, koji je jedan od glavnih ĉimbenika u razvoju grada, a osim prirodnih uvjeta, kroz rad nastojim prikazati ostale uvjete koji su utjecali na razvoj Zagreba i njegovu prostornu organizaciju.