Bernard Lonergan's the Triune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reverend Matthew L. Lamb

Fr. Matthew L. Lamb’s C.V. Summer 2014 Reverend Matthew L. Lamb Priest of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee Professor of Theology Ave Maria University 5050 Ave Maria Boulevard Ave Maria, Florida 34142-9670 Tel. 239-867-4433 [email protected] [email protected] I. EDUCATION: 1974 Doktor der Theologie summa cum laude, Catholic Faculty of Theology, Westfälsche Wilhelms University, Münster, Germany. 1967-71 Doctoral studies, University of Tübingen (one semester) and Münster (six semesters). 1966 S.T.L. cum laude, the Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome, Italy. 1964-67 Graduate studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. August 14, 1962 ordained to the Roman Catholic Priesthood, Trappist Monastery of the Holy Spirit, Conyers, Georgia; now a Roman Catholic priest incardinated in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee. 1960-64 Theological studies at the Trappist Monastic Scholasticate, Monastery of the Holy Spirit, Conyers, Georgia. 1957-60 Philosophical studies at the Trappist Monastic Scholasticate, Conyers, Georgia. II. TEACHING: A. Marquette University, College of Arts & Sciences 1973-74 Instructor in Systematic Theology B. Marquette University, Graduate School 1974-79 Assistant Professor of Fundamental Theology 1979-85 Associate Professor of Fundamental Theology C. University of Chicago, Divinity School & Graduate School 1980 Visiting Associate Professor in Philosophical Theology. Page 1 of 44 Fr. Matthew L. Lamb’s C.V. Summer 2014 D. Boston College, College of Arts and Sciences, Graduate School 1985-88 Associate Professor of Theology 1989 - 2004 Professor of Theology E. Ave Maria University, Department of Theology 2004 - Professor of Theology and Chairman III. GRANTS AND ACADEMIC HONORS: 2009 – Cardinal Maida Chair, Ave Maria University. -

Bo St O N College F a C T B

BOSTON BOSTON COLLEGE 2012–2013 FACT BOOK BOSTON COLLEGE FACT BOOK 2012-2013 Current and past issues of the Boston College Fact Book are available on the Boston College web site at www.bc.edu/factbook © Trustees of Boston College 1983-2013 2 Foreword Foreword The Office of Institutional Research is pleased to present the Boston College Fact Book, 2012-2013, the 40th edition of this publication. This book is intended as a single, readily accessible, consistent source of information about the Boston College community, its resources, and its operations. It is a summary of institutional data gathered from many areas of the University, compiled to capture the 2011-2012 Fiscal and Academic Year, and the fall semester of the 2012-2013 Academic Year. Where appropriate, multiple years of data are provided for historical perspective. While not all-encompassing, the Fact Book does provide pertinent facts and figures valuable to administrators, faculty, staff, and students. Sincere appreciation is extended to all contributors who offered their time and expertise to maintain the greatest possible accuracy and standardization of the data. Special thanks go to graduate student Monique Ouimette for her extensive contribution. A concerted effort is made to make this publication an increasingly more useful reference, at the same time enhancing your understanding of the scope and progress of the University. We welcome your comments and suggestions toward these goals. This Fact Book, as well as those from previous years, is available in its entirety at www.bc.edu/factbook. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

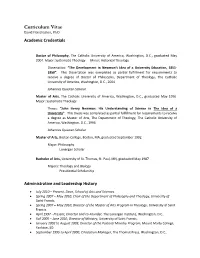

Curriculum Vitae David Fleischacker, Ph.D

Curriculum Vitae David Fleischacker, Ph.D. Academic Credentials Doctor of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., graduated May 2004. Major: Systematic Theology Minor: Historical Theology Dissertation: “The Development in Newman’s Idea of a University Education, 1851- 1858”. This Dissertation was completed as partial fulfillment for requirements to receive a degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Theology, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., 2004 Johannes Quasten Scholar Master of Arts, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., graduated May 1996. Major: Systematic Theology Thesis: “John Henry Newman: His Understanding of Science in The Idea of a University”. This thesis was completed as partial fulfillment for requirements to receive a degree as Master of Arts, The Department of Theology, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., 1996. Johannes Quasten Scholar Master of Arts, Boston College, Boston, MA, graduated September 1992. Major: Philosophy Lonergan Scholar Bachelor of Arts, University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN, graduated May 1987 Majors: Theology and Biology Presidential Scholarship Administrative and Leadership History • July 2010 – Present, Dean, School of Arts and Sciences. • Spring 2007 – May 2010, Chair of the Department of Philosophy and Theology, University of Saint Francis. • Spring 2007 – May 2010, Director of the Master of Arts Program in Theology, University of Saint Francis. • April 1997 - Present, Director and co-Founder, The Lonergan Institute, Washington, D.C.. • Fall 2005 – June 2010, Director of Ministry, University of Saint Francis. • January 2002 to August 2003, Director of the Pastoral Ministry Program, Mount Marty College, Yankton, SD. • September 1995 to April 2000, Circulation Manager, The Thomist Press, Washington, D.C. -

2000–2001 Fact Book

boston college FACT BOOK 2001 The Boston College Fact Book is on the World Wide Web! Current and past issues are available on the Boston College web site at http://www.bc.edu/factbook Nondiscrimination Statement Founded by the Society of Jesus in 1863, Boston College is dedicated to intellectual excellence and to its Jesuit, Catholic mission and heritage. Committed to maintaining a welcoming environment for all people, the University recognizes the important contribution a diverse community of students, faculty and administrators makes to the advancement of its goals and ideals. Boston College rejects and condemns all forms of harassment, and it has developed procedures to redress incidents of harassment against any members of its community, whatever the basis or circumstance. Moreover, in accordance with all applicable state and federal laws, Boston College does not discriminate in employment, housing, or education on the basis of a person’s race, religion, color, national origin, age, sex, marital or parental status, veteran status, or disabilities. In addition, in a manner faithful to the Jesuit, Catholic principles and values that sustain its mission and heritage, Boston College is in compliance with applicable state laws providing equal opportunity without regard to sexual orientation. Boston College has designated the Director of Affirmative Action to coordinate its efforts to comply with and carry out its responsibilities to prevent discrimination in accordance with state and federal laws. Any applicant for admission or employment, as well as all students, faculty members, and employees, are welcome to raise any questions regarding violation of this policy with Barbara Marshall, Director of Affirmative Action, More Hall 315, 552-2947. -

Boston College FACT BOOK

Boston College FACT BOOK 2002-2003 Containing data from Fiscal Year 2001-2002, Academic Year 2001-2002, and Fall of Academic Year 2002-2003 Current and past issues of the Boston College Fact Book are available on the Boston College web site at http://www.bc.edu/factbook 2 Foreword Foreword The Boston College Fact Book captures and summarizes much of the important current and historical information about Boston College. The Fact Book is intended to serve as a reference for information about the University’s faculty, students, alumni, personnel, facilities, and budget. Although the Fact Book is generally published annually, this current edition is the first to be published since the 2000-2001 Fact Book was released in August 2001. The 2002-2003 Boston College Fact Book reflects year-end data from the 2001-2002 fiscal and academic years. In certain in- stances, information relating to the fall of 2002 (academic year 2002-2003) is presented. Much of the information contained in the Fact Book is cumulative and references annual data for the preceding five or ten year period. Other information is presented in a single year format. Because of the gap in publication of the Fact Book, single-year data for the 2000-2001 fiscal and academic years has been preserved in the 2001-2002 Supplemental Edition, accessible on the Web at http://www.bc.edu/factbook. We are grateful to the many departments and individuals who provided data for this book - the 30th edition of the Fact Book. The majority of the information is extracted from reports produced on a regular basis by the various source offices. -

Curriculum Vita: Stephen J. Pfohl Address: Sociology Department

Curriculum Vita: Stephen J. Pfohl Address: Sociology Department Boston College Chestnut Hill, MA 02167 (617) 552-4135 e-mail: [email protected] Education B.A., 1971, Sociology, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. Undergraduate Thesis: “Social Psychological Consequences of the Posture of Non-Violence.” M.A., 1972, Sociology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Ph.D., 1976, Sociology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Dissertation: The Social Construction of Psychiatric Reality: A Study of Diagnostic Procedures in a Forensic Psychiatric Institution. Postdoctoral Studies, 1981-82, Sociology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. Major Fields of Interest Social Theory/ Interpretive Methods Deviance and Social Control/ Critical Criminology Cultural Studies/ Social Psychoanalysis/ Images and Power Global Social Studies/ Postmodern Ethnography Teaching/University Experience 1. Teaching Associate in Sociology at The Ohio State University, 1972-73, courses in Social Problems, Criminology, Introduction to Sociology. 2. Principal Instructor (Teaching Associate) at The Ohio State University, 1973- 74, lower division courses in Introduction to Sociology and Social Problems, Upper Division course in Social Psychology. 3. Lecturer at The Ohio State University, January-August., 1977. Undergraduate courses in the Sociology of Deviance, Social Psychology, and Criminology. 4. Assistant/Associate Professor of Sociology, Boston College, 1977-1993. Graduate and undergraduate courses in Criminology, Deviance and Social Control, Field Research, Interpretive Sociology, Sociological Theory. 5. Professor of Sociology, Boston College, 1993 to present. Graduate and undergraduate courses in Social Theory; Cultural Studies; Images and Power; Postmodernity and Social Theory; Desire and Narrative; Sociology and Psychoanalysis; Crime, Deviance and Social Control; Crime and Social Studies; Critical Studies in Social Control. -

1 Understanding Aristotle Lonergan Institute for the “Good Under

1 Understanding Aristotle Lonergan Institute for the “Good Under Construction” In Aristotle, there are not two sets of objects but two approaches to one set. Theory is concerned with what is prior in itself but posterior for us; but everyday human knowledge is concerned with what is prior for us though posterior in itself. But, though Aristotle by beguilingly simple analogies could set up a properly systematic metaphysics, his contrast was not between theory and common sense as we understand these terms but between episteme and doxa, between sophia and phronesis, between necessity and contingence...in Aristotle the sciences are conceived not as autonomous but as prolongations of philosophy and as further determinations of the basic concepts philosophy provides. So it is that, while Aristotelian psychology is not without profound insight into human sensibility and intelligence, still its basic concepts are derived not from intentional consciousness but from metaphysics. Thus “soul” does not mean “subject” but “the first act of an organic body” whether of a plant, an animal, or a man.44 Similarly, the notion of “object” is not derived from a consideration of intentional acts; on the contrary, just as potencies are to be conceived by considering their acts, so acts are to be conceived by considering their objects, i.e. their efficient or final causes.45 As in psychology, so too in physics, the basic concepts are metaphysical. As an agent is principle of movement in the mover, so a nature is principle of movement in the moved. But agent is agent because it is in act. -

Boston College

BOSTON COLLEGE Fact Book 2013-2014 EVER TO EXCEL BOSTON COLLEGE FACT BOOK 2013-2014 Current and past issues of the Boston College Fact Book are available on the Boston College web site at www.bc.edu/factbook © Trustees of Boston College 1983-2014 2 Foreword Foreword The Office of Institutional Research is pleased to present the Boston College Fact Book, 2013-2014, the 41st edition of this publication. This book is intended as a single, readily accessible, consistent source of information about the Boston College community, its resources, and its operations. It is a summary of institutional data gathered from many areas of the University, compiled to capture the 2012-2013 Fiscal and Academic Year, and the fall semester of the 2013-2014 Academic Year. Where appropriate, multiple years of data are provided for historical perspective. While not all-encompassing, the Fact Book does provide pertinent facts and figures valuable to administrators, faculty, staff, and students. Sincere appreciation is extended to all contributors who offered their time and expertise to maintain the greatest possible accuracy and standardization of the data. Special thanks go to graduate student Monique Ouimette for her extensive contribution. A concerted effort is made to make this publication an increasingly more useful reference, at the same time enhancing your understanding of the scope and progress of the University. We welcome your comments and suggestions toward these goals. This Fact Book, as well as those from previous years, is available in its entirety -

PUBLICATIONS Arcamone, Dominic

NEWSLETTER 4 2 / 1 M A R C H 2021 PUBLICATIONS Arcamone, Dominic. Conversion as Transformation: Lonergan, Mentors and Cinema. Eugene OR: Pickwick Publications, 2020. Blackwood, Jeremy W. “Response to ‘Understanding the God of Love: An Essay on Lonergan’s Systematics of the Trinity.’” The Lonergan Review 11 (2020): 125-134. doi: https://doi.org/10.5840/lonerganreview2020117. Byrne, Patrick H. “Curiosity: Vice or Virtue? Augustine and Lonergan.” American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly 95/1 (2021): 69-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.5840/acpq2020127215. Two recent studies by Joseph Torchia and Paul Griffiths show the importance of Augustine’s critique of the vice of curiositas to contemporary life and thought. Superficially, it might seem that Augustine condemned curiosity because it “seeks to find out whatever it wishes without restriction of any kind.” Though profoundly influenced by Augustine, Bernard Lonergan praised intellectual curiosity precisely insofar as it is motivated by an unrestricted desire to know, rather than by less noble motives. Drawing upon the researches of Torchia and Griffiths, this article endeavors to show that Augustine does not simply equate curiositas with an unrestricted desire to know, and that the virtue of intellectual curiosity as Lonergan understood it is in fact endorsed by Augustine by means of its relationship to the virtue of studiositas. This more nuanced view of the virtues and vices of intellect can provide guidance for contemporary intellectual pursuits, both how to pursue and not to pursue knowledge. Coghlan, David. “Fostering Undergraduate Research through insider inquiry: Exploiting student work Experiences.” Management Teaching Review 6/1, (2021): 66–72. -

Journal of Lonergan Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2

pfturnalgf&tnergnn Eniloes VOLUME14 NUMBER2 FALL1996 METHID: lournal of LonerganStudies airns, first, at furthering interpretive, historical and critical study of the philosophical, theological,economic, and methodologicalwritings of Bernard Lonergan. Secondly, it aims at promoting original research into the methodologicalfoundations of the sciencesand disciplines. METHzDis published twice yearly, in April and October, by The Lonergan Institute at BostonCollege. SuBscRtPrtoNPRICE 1996: $14.00 yearly for individuals, $25.00yearly for institutions (U-S- currency). SuBscRIPrIoNORDERs must be prepaid in U.S. funds and should be addressed to the BusinessManager, Meruoo, Lonergan Center, Bapst Library, Boston College, Chestnut HilL MA 02167-3806.Changes of address and other correspondence related to subscriptionsand advertising should be sent to the sameaddress. MANUscRtPTsshould be sent to Mark Morelli, METHoD,Deparhnent of Philosophy, Loyola Marymount University, Loyola Blvd. at W. 80th Street,Los Angeles, CA 90M5 or to Patrick Byrne, METHoD,Department of Philosophy, Carney Hall 216, Boston College, Chestnut HiU, MA 02'167.3806.In order to facilitate an early decision, authors should send,three copies of each manuscripi double-spacedthroughout, including footnotes. Submissionsshould be accompaniedby a short biographical note. They can be returned only if adequatepostage is included. Accepted articles must follow A Manual o/S{rle (University of ChicagoPress) and should be submitted in this form. Referencesto any of Lonergan s writings that -

Father Matthew L. Lamb

Fr. Matthew L. Lamb’s C.V. June 2016 Father Matthew L. Lamb Priest of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee Professor of Theology Ave Maria University 5068 Annunciation Circle #203 Ave Maria, Florida 34142-9670 Tel. 239-216-1024 [email protected] [email protected] I. EDUCATION: 1974 Doktor der Theologie summa cum laude, Catholic Faculty of Theology, Westfälsche Wilhelms University, Münster, Germany. 1967-71 Doctoral studies, University of Tübingen (one semester) and Münster (six semesters). 1966 S.T.L. cum laude, the Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome, Italy. 1964-67 Graduate studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. August 14, 1962 ordained to the Roman Catholic Priesthood, Trappist Monastery of the Holy Spirit, Conyers, Georgia; now a Roman Catholic priest incardinated in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee. 1960-64 Theological studies at the Trappist Monastic Scholasticate, Monastery of the Holy Spirit, Conyers, Georgia. 1957-60 Philosophical studies at the Trappist Monastic Scholasticate, Conyers, Georgia. II. TEACHING: A. Marquette University, College of Arts & Sciences 1973-74 Instructor in Systematic Theology B. Marquette University, Graduate School 1974-79 Assistant Professor of Fundamental Theology 1979-85 Associate Professor of Fundamental Theology C. University of Chicago, Divinity School & Graduate School 1980 Visiting Associate Professor in Philosophical Theology. Page 1 of 44 Fr. Matthew L. Lamb’s C.V. June 2016 D. Boston College, College of Arts and Sciences, Graduate School 1985-88 Associate Professor of Theology 1989 - 2004 Professor of Theology E. Ave Maria University, Department of Theology 2004 - 2014 Professor of Theology and Chairman 2015 - Professor of Theology III. GRANTS AND ACADEMIC HONORS: 2016 – Lifetime Achievement Award, American Maritain Association 2014 – Veritas Medal, Ave Maria University 2013 – Robert Bellarmine Award, Pontifical Gregorian University 2009 – Cardinal Maida Chair, Ave Maria University.