Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unkans ISSUE JUNE 2015 the Newsletter of the Shetland Heritage and Culture Community Issue 50 a Look Back on fi Fty Issues Unkans Has Reached a Milestone 50Th Issue

50th FREE Unkans ISSUE JUNE 2015 The newsletter of the Shetland Heritage and Culture Community Issue 50 A look back on fi fty issues Unkans has reached a milestone 50th issue. to become a publication dedicated to the introduction of an online mailing list. Now The newsletter was first produced in March promotion of activities of the wider heritage readers from all around the world can sign 2007 to inform and update the community and culture community in Shetland. Emma up to receive the latest issue direct to their about events, research and services provided Miller, Marketing Officer at Shetland inbox. The readership now extends from by the brand new Shetland Museum and Amenity Trust took on the role of editor. Canada to Australia and New Zealand with Archives. Assistant Archivist, Joanne Since its inception, Unkans has always been many places in between including Norway, Wishart, and Curator, Dr Carol Christiansen, available to download from the Shetland Italy and Hong Kong. worked together as joint editors. Articles Museum and Archives website, and all back Article contributions are always welcome relating to the wider Shetland heritage issues from the very first are still online. on any subject relating to Shetland’s community were also welcomed. In February 2013, Unkans moved a further heritage and culture. Here’s to the next 50 In July 2012 Unkans was rebranded step forward in the digital world with the issues! The Victoress – a family heirloom in Hoswick, it had spent all of its life didn’t have room in our house, so in my great aunt Helen Jamieson’s my forgiving in-laws, Richard and house in Guddon, East Yell. -

January 2021 Newsletter

Scottish Heritage USA NEWSLETTER JANUARY 2021 Vikings leading the Hogmanay Torchlight Parade, Edinburgh ISSUE #1-2021 HAPPY NEW YEAR & HAPPY HOGMANAY! H OGMANAY may be Scotland’s New Year celebration, but it lasts three to five days with unusual, weird and wild H traditions. It starts on Christmas with the Edinburgh Torchlight Parade and is all downhill from there! Look to Scotland to find the best, most spectacular fire festivals in the UK. Combine the primitive impulse to light up the long nights (the ancient idea that fire purifies and chases away evil spirits) and the natural Scottish impulse to party to the wee small hours and you end up with some of the most dazzling and daring midwinter celebrations in Europe. At one time, most Scottish towns celebrated the New Year with huge bonfires and torchlight processions. Many have disappeared, but those that are left are real Site where the horde was found humdingers. Here are the five of the best winter fire festivals in Scotland: STONEHAVEN FIRE FESTIVAL: Strong Scots dare-devils parade through the town on New Year's Eve swinging 16-pound balls of fire around themselves and over their heads. Each "swinger" has his or her own secret recipe for creating the fireball and keeping it lit. Thousands come to watch this famous event on the North Sea, south of Aberdeen. It all gets underway before midnight with bands of pipers and wild drumming. Then a lone piper, playing Scotland the Brave, leads the pipers into town. At the stroke of midnight, they raise their flaming balls over their heads and begin to swing and twirl them, showering the street, themselves and usually the 12,000 strong crowd, with sparks. -

Auld Rock Meets Nordic Noir: a Danish Gaze on Shetlandic Scandinavian-Ness

Auld Rock meets Nordic Noir: A Danish Gaze on Shetlandic Scandinavian-ness By Gunhild Agger, Hanne Tange The Scandinavian traveller arriving through Sumburgh is greeted in a homely way. On the road taking drivers out of the airport area stands a multilingual sign, which welcomes voyagers in the four languages of English, Norwegian, German and French. To the Scandinavian the sign is an oddity, signalling at once historical connectivity and geographical distance. For while the choice of Norwegian acknowledges Shetland’s legacy as a nodal point connecting the string of islands making up a Viking kingdom stretching from Bergen to Dublin, any present-day visitor from Nordic Europe will inevitably arrive through British (air)ports such as Edinburgh, Glasgow or Aberdeen, which would be difficult if s/he was capable of managing in a Scandinavian language alone. To provide information in Norwegian seems unnecessary, leaving one to wonder what exactly is the purpose of the Sumburgh signpost? The authors rely in this paper on a specific reading of signs, accepting their power to create simultaneously a sense of connectivity and distance. The core concept of connectivity is inspired by the Swedish anthropologist Ulf Hannerz1, who argues how shared migration experiences, cultural representations, communication and trade networks evoke in people the feeling of being related to communities positioned in other parts of the world. Connectivity builds on a logic of similarity, suggesting that relationships create a shared we-ness, which is reinforced through the cultural practices, traditions and symbols linking a historic settler society such as Shetland, to Norway, as the Shetlanders’ imaginary ‘land of the fathers’.2 The Sumburgh signpost offers a physical expression of connectivity where Norwegian, as a linguistic sign, is selected because it can communicate both a Shetlandic desire to connect with Norway/Scandinavia and a perceived sense of distance, linguistic and cultural, to the British Mainland and Scotland in particular. -

SB-4207-January

Scottishthethethethe www.scottishbanner.com Banner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 42 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 42 36 36 NumberNumber Number 711 11 TheThe The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international ScottishScottish Scottish newspaper newspaper May January May 2013 2013 2019 Up Helly Aa Lighting up Shetland’s dark winter with Viking fun » Pg 16 2019 - A Year in Piping » Pg 19 USAustralia Barcodes $4.00; N.Z. $4.95 A Literary Inn ............................ » Pg 8 The Bards Scotland: What’s New for 2019 ............................. » Pg 12 Discover Scotland’s Starry Nights .............................. » Pg 15 Family 7 25286 844598 0 1 The Immortal Memory ........ » Pg 29 » Pg 25 7 25286 844598 0 9 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 42 - Number 7 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Offices of publication Valerie Cairney Australasian Office: PO Box 6202 Editor Marrickville South, Starting the year Sean Cairney NSW, 2204 Tel:(02) 9559-6348 EDITORIAL STAFF Jim Stoddart [email protected] Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot The National Piping Centre North American Office: off Scottish style PO Box 6880 David McVey Cathedral you were a Doonie, with From Scotland to the world, Burns Angus Whitson Hudson, FL 34674 Lady Fiona MacGregor [email protected] Uppies being those born to the south, Suppers will celebrate this great Eric Bryan or you play on the side that your literary figure from Africa to America. -

Three Festivals

Leggi e ascolta. Three festivals Up Helly Aa On the last Tuesday of every January, local men in the town of Lerwick, in the Shetland Islands, go a little crazy! Teams of men called Guizers parade through the streets to celebrate the festival of Up Helly Aa – and they all wear Viking costumes. Up Helly Aa started in the 1800s, but it comes from an old Viking festival to celebrate the sun. After sunset, four or five thousand people watch as one group of Guizers pulls a wooden Viking boat through the streets! About a thousand Guizers follow them with burning torches. They burn the boat in the town centre, and perform dances and songs around the town – the parties continue until the next morning! Preparations for the next Up Helly Aa start again in February. The Guizers – all men – practise in groups, make the costumes and build the boat. It takes months of hard work to build a Viking boat, but only one hour to burn it! High Five Exam Trainer . Oral presentation 3, Culture: Scottish festivals p. 44 © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE The Cowal Highland Gathering Traditional events called Highland Games happen all year in different parts of Scotland. The Games started in the 1820s, with competitions for traditional sports, music and dancing. The biggest event is the Cowal Highland Gathering, at Dunoon. Thirty thousand people come from all over the world for three days at the end of August to watch strange sports events. In tossing the caber, strong men throw big tree logs. In the stone put, men and women throw a stone ball as far as they can. -

Traditions and Holidays in the Uk and the Usa

TRADITIONS AND HOLIDAYS IN THE UK AND THE USA JANUARY UP-HELLY-AA (UK) The Shetlands are islands near Scotland. In the ninth century men from Norway came to the Shetlands. These were the Vikings. They came to Britain in ships and carried away animals, gold, and sometimes women and children, too. Now, 1,000 years later, people in the Shetlands remember the Vikings with a festival. They call the festival ”Up-Helly-Aa”. Every winter the people of Lerwick, a town in the Shetlands, make a model of a ship. It's a Viking ”longship”, with the head of a dragon at the front. Then, on Up-Helly-Aa night in January, the Shetlanders dress in Viking clothes. They carry the ship through the town to the sea. There they burn it. They do this because the Vikings put their dead men in ships and burned them. But there aren't any men in the modern ships. Now the festival is a party for the people of the Shetland Islands. THE THIRD MONDAY OF JANUARY MARTIN LUTHER KING’S BIRTHDAY (USA) Martin Luther King was an important black leader who wanted equality for black people and fought for their civil rights. Preaching non-violence as Gandhi he tried not to consider the blacks as second-class citizens. He was murdered in 1968. Because of his work, Congress made his birthday a public holiday in 1986. FEBRUARY FEBRUARY 14TH – ST. VALENTINE’S DAY (UK, USA) Nobody knows very much about St. Valentine. One story is that he was murdered by Roman soldiers in the third century AD because he was a Christian. -

Download: 11 November 2019 NCC Minutes

NORTHMAVEN COMMUNITY COUNCIL Chair: David Brown Clerk: NCDC Services Crogreen C/o Ollaberry Hall Ollaberry Ollaberry Tele: 01806 544374 ZE2 9RT Telephone: 01806 544222 E-mail: [email protected] Minute of Ordinary Meeting of the Council on Monday 11th November 2019 In Ollaberry Primary School This minute is UNAPPROVED until adopted at the next meeting Present: CCllr D Brown (Chair) CCllr K Williamson CCllr R Doull (Vice Chair) CCllr B Wilcock CCllr D Robertson CCllr K Scollay 1. Apologies Submitted: CCllr J A Cromarty Ex Officio Present: CCllr E Robertson Mrs R Fraser – SIC Community Worker Ex Officio Apologies Mr M Duncan – SIC Community Worker Cllr E Macdonald In attendance: Ms C Sutherland – Clerk PC Jamie Henderson – Police Scotland Pete & Jan Bevington The meeting started at: 7.30pm, CCllr D Brown in the Chair. Agenda Item Narrative 2. Declaration of None interest 3. Approval Of The minute of the meeting held in Ollaberry Primary School on Previous Minute Monday 14th October 2019 approved: CCllr K Williamson, seconded: CCllr D Robertson. 4. Police report PC Jamie Henderson informed members that Police Scotland have started their Winter Safety Campaign which will run until January. They will be doing speed checks and vehicle checks. He also stated they would be focusing on ensuring young people knew how to drive in wintry conditions. 5. Matters arising Previous visit from Capt Maitland – SIC Ports & Harbours. Nothing further. It was agreed that members will continue to monitor infrastructure at the pier. NCDC No update. 1 Broadband An e-mail has been received from D Lamont at BT regarding the 4g EE mast at North Roe. -

To See the 2020 Programme

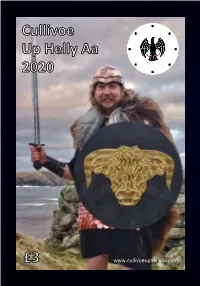

www.cullivoeuphellyaa.comwww.cullivoeuphellyaa.com Wir Guizer Jarl - Craig Dickie Craig is a Cullivoe man through and through, although his work has taken him all over Scotland in the last few years. Growing up in North Yell, Craig has always looked forward to taking part in Up Helly Aa, first with the school squad, before becoming a member of the 'Young Turks' in 2003. Craig’s first Jarl Squad outing was with his brother Campbell, who was Jarl in 2011, following the tradition of their father Hubert, who was Jarl in 1977. Outgoing Jarl James Nicholson asked Craig if he would be interested in taking the helm, and Craig has been honoured to. In 2013, Craig's wife Becky bought him three Highland cattle, and the hobby has grown since, so the mascot for this year's festival is Craig’s new Highland bull Chieftain of Tordarroch. Alongside the 15 men in the squad are Craig's three children Jessica (14), Monica (11) and Rosie (10) who are participating as Viking Warriors, and are looking forward to taking their battle stations. All three of the girls have loved taking part in the schools’ Up Helly Aa traditions - the festival is very much in their Cullivoe DNA. Up Helly Aa wouldn't happen without the support of so many members of the community and wider area. In particular Craig would like to thank James for his nomination, all of the squad for their uproarious support and help, his wonderful musicians who have provided them with many great tunes, the galley builders, the South Mainland Up Helly Aa committee members who have allowed us the use of their blueprints, and for their warm welcome in Cunningsburgh. -

Download 2015/16 Annual Report

SHETLAND AMENITY TRUST Shetland Amenity Trust Annual Report 2015/2016 1 SHETLAND AMENITY TRUST INTRODUCTION July 2015 saw the launch of the €3.92 million Follow The Vikings project . Shetland Amenity Trust is the lead partner in this exciting transnational project which has 15 full partners and 10 associate partners with a geographical spread over 13 countries. The 4-year project will celebrate Viking heritage throughout Europe and will have a particular emphasis on creativity and culture, including the creation of a website and an international touring event. There will also be an emphasis on training volunteers at a local level and skills exchange. The project will seek to develop audiences through a variety of new technologies, build business models through sharing best practice and will strengthen the international network of professionals and institutions working in the field of Viking heritage. As we approach the end of the year, the prospect of further reductions in core funding will bring new challenges to the Trust in its role as a champion of Shetland’s Culture and Heritage. We are confident that we will be able to continue to deliver a high quality service to Shetland. 2 SHETLAND AMENITY TRUST TRUST OBJECTIVES General The Trust objectives are: At the Trust’s AGM in September 2015 Mr L. Johnston retired from the Trust. A secret ballot was held at which (a) The protection, improvement and enhancement 4 nominations were considered and Mr A. Blackadder, Mr of buildings and artefacts of architectural, historical, B. Gregson and Mr J. Henry were re-elected as Trustees educational or other interest in Shetland with a view and Mr A. -

2019 Calendar of Events UK & Ireland

2019 Calendar of Events UK & Ireland Creative | Connected | People 2019 CALENDAR OF EVENTS ENGLAND SCOTLAND IRELAND 12 Jan-9 Feb: Cirque du Soleil - Totem, The Royal Albert Hall, London 11: Scalloway Fire Festival 7-13: Dublin Bowie Festival 16-20: London Art Fair 17 Jan-3 Feb: Celtic Connections Festival, Glasgow 17-21: Shannonside Winter Music Festival 25: Burns Night Celebrations 23-27: Temple Bar Tradfest, Dublin Jan 26-27: Aviemore Dog Sled Rally, Glenmore 29: Up Helly Aa, Shetland 2 Feb-14 Jul: Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams. The V&A, London 2: Six Nations Rugby (Scotland Vs Italy) BT Murrayfield Stadium, 2: Six Nations Rugby (Ireland Vs England) Aviva Stadium, Dublin 5: Chinese New Year Edinburgh 2-3: Dublin Racing Festival, Leopardstown 8: Opening - Mandela: The Official Exhibition, 26 Leake St. London 9: Six Nations Rugby (Scotland Vs Ireland) BT Murrayfield Stadium, 20 Feb-3 Mar: Virgin Media Dublin International Film Festival 10: Six Nations Rugby (England Vs France) Twickenham Stadium, Edinburgh 27 Feb-3 Mar: The Gathering Traditional Festival, Killarney London 20-24: Fort William Mountain Festival Feb 14-17: The London Classic Car Show 20 Feb-3 Mar: Glasgow Film Festival 16-20: London Fashion Week AW19, London 23: Six Nations Rugby (Wales Vs England) Principality Stadium, Cardiff 7 Mar-27 May: Only Human: Photographs by Martin Parr. National 6-10: StAnza, International Poetry Festival, St Andrews 10: Six Nations Rugby (Ireland Vs France) Aviva Stadium, Dublin Portrait Gallery, London 9: Six Nations Rugby (Scotland Vs Wales) BT Murrayfield Stadium, 14-18: St Patrick’s Festival, Dublin 9: Six Nations Rugby (England Vs Italy) Twickenham Stadium Edinburgh 17: St Patrick’s Day 12-15: Cheltenham National Hunt Festival, Gloucester 11-21: Ayrshire Music Festival, Ayr 20-23: Cork International Poetry Festival 16: Six Nations Rugby (England Vs Scotland) Twickenham Stadium 14-31: Glasgow International Comedy Festival 21-24: Dingle International Film Festival Mar 27 Mar-11 Aug: The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain. -

A Very Brief History of Up-Helly-Aa

The Galley’s role in Up-Helly-Aa The significance of the name Up- Helly-Aa has been variously interpreted over the years, but most commentators suggest that the expression owes its modern form to the Old Norse for weekend or holiday being the word Helly, thus Up-Helly-Aa being the end of helly or holidays. In its modern form the festival is not all that old with the addition of Galleys and a Viking A galley from the late 1980s with group of boys theme only coming about just over closely inspecting 100 years ago. ‘There was a strongly romantic Nordic revival towards the end of the nineteenth century, and it was perhaps unavoidable that the festival would somehow become tied with the Vikings. The first galley was burnt in 1889’.1 Prior to this, festivities included flaming tar- barrels being dragged through the street accompanied by indiscriminate gunfire. Regulation of ‘end of Yule’ celebrations came about in 1874 when the town clerk posted his final warning to the tar-barrellers. Interestingly, an N.B. at the end of the order states that ‘the commissioners have no intention of interfering with out-door harmless amusements’.2 Indeed, around the end of the 19th Century, Up-Helly-Aa evolved into a ‘harmless amusement’ and a self-policing event. Former tar-barrellers now instigated properly organised routes, rules for conduct and (should the Close-up of galley’s head need arise) discipline of participants, and marshals to oversee the procession itself. The prevailing spirit of Up-Helly-Aa was and still is one of comradeship, courtesy, conviviality, music, dancing and above all fun. -

Customs and Traditions in Britain Stephen Rabley Introduction

Customs and Traditions in Britain Stephen Rabley Introduction Some British customs and traditions are famous all over the world. Bowler hats, tea and talking about the weather, for example. But what about the others? Who was Guy Fawkes? Why does the Queen have two birthdays? And what is the word “pub” short for? You can find the answers here in this book on traditional British life. From Scotland to Cornwall, Britain is full of customs and traditions. A lot of them have very long histories. Some are funny and some are strange. But they’re all interesting. There are all the traditions of British sport and music. There’s the long menu of traditional British food. There are many royal occasions. There are songs, sayings and superstitions. They are all part of the British way of life. A year in Britain JANUARY Up-Helly-Aa The Shetlands are islands near Scotland. In the ninth century, men from Norway came to the Shetlands. These were the Vikings. They came to Britain in ships and carried away animals, gold, and sometimes women and children, too. Now, 1,000 years later, people in the Shetlands remember the Vikings with a festival. They call the festival “Up-Helly-Aa”. Every winter the people of Lerwick, a town in the Shetlands, make a model of a ship. It’s a Viking “long-ship”, with the head of a dragon at the front. Then, on Up-Helly-Aa night in January, the Shetlanders dress in Viking clothes. They carry the ship through the town to the sea.