In Search of Lost Time: Redefining Socialist Realism in 1950S DPRK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

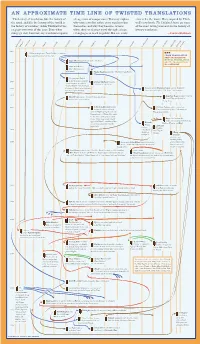

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

Bibliography

SELECTED bibliOgraPhy “Komentó: Gendai bijutsu no dōkō ten” [Comment: “Sakkazō no gakai: Chikaku wa kyobō nanoka” “Kiki ni tatsu gendai bijutsu: henkaku no fūka Trends in contemporary art exhibitions]. Kyoto [The collapse of the artist portrait: Is perception a aratana nihirizumu no tōrai ga” [The crisis of Compiled by Mika Yoshitake National Museum of Art, 1969. delusion?]. Yomiuri Newspaper, Dec. 21, 1969. contemporary art: The erosion of change, the coming of a new nihilism]. Yomiuri Newspaper, “Happening no nai Happening” [A Happening “Soku no sekai” [The world as it is]. In Ba So Ji OPEN July 17, 1971. without a Happening]. Interia, no. 122 (May 1969): (Place-Phase-Time), edited by Sekine Nobuo. Tokyo: pp. 44–45. privately printed, 1970. “Obŭje sasang ŭi chŏngch’ewa kŭ haengbang” [The identity and place of objet ideology]. Hongik Misul “Sekai to kōzō: Taishō no gakai (gendai bijutsu “Ningen no kaitai” [Dismantling the human being]. (1972). ronkō)” [World and structure: Collapse of the object SD, no. 63 (Jan. 1970): pp. 83–87. (Theory on contemporary art)]. Design hihyō, no. 9 “Hyōgen ni okeru riaritī no yōsei” [The call for the Publication information has been provided to the greatest extent available. (June 1969): pp. 121–33. “Deai o motomete” (Tokushū: Hatsugen suru reality of expression]. Bijutsu techō 24, no. 351 shinjin tachi: Higeijutsu no chihei kara) [In search of (Jan. 1972): pp. 70–74. “Sonzai to mu o koete: Sekine Nobuo-ron” [Beyond encounter (Special issue: Voices of new artists: From being and nothingness: On Sekine Nobuo]. Sansai, the realm of nonart)]. Bijutsu techō, no. -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

B. 1973 in Seoul, South Korea; Lives and Works in Baltimore, New York, and Seoul

Mina Cheon CV 2021 Mina Cheon (천민정) (b. 1973 in Seoul, South Korea; lives and works in Baltimore, New York, and Seoul) Mina Cheon is a new media artist, sCholar, eduCator, and activist best known for her “Polipop” paintings inspired by Pop art and Social Realism. Cheon’s practice draws inspiration from the partition of the Korean peninsula, exemplified by her parallel body of work created under her North Korean alter ego, Kim Il Soon, in which she enlists a range of mediums inCluding painting, sCulpture, video, installation, and performanCe to deConstruCt and reConCile the fraught history and ongoing coexistence between North and South Korea. She has exhibited internationally, including at the Busan Biennale (2018); Baltimore Museum of Art (2018); American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, Washington, DC (2014); Sungkok Art Museum, Seoul (2012); and Insa Art SpaCe, Seoul (2005). Her work is in the colleCtions of the Baltimore Museum of Art; Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton; and Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. Currently, she is working on her participation for the inaugural Asia SoCiety Triennial 2020-2021 titled, “We Do Not Dream Alone.” Her digital interactive art piece, EatChocopieTogether.com for global peaCe, was launChed on August 15, 2020 and will remain active for virtual participation as a lead up to the physical exhibition of Eat Chocopie Together at the end of the Triennial. Mina Cheon is the author of Shamanism + CyberspaCe (Atropos Press, Dresden and New York, 2009), contributor for ArtUS, Wolgan Misool, New York Arts Magazine, Artist Organized Art, and served on the Board of Directors of the New Media CauCus of the College Art AssoCiation, as well as an AssoCiate Editor of the peer review aCademiC journal Media-N. -

Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust. John Stephen Larose Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Larose, John Stephen, "Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7206. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7206 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 52 (2016) 207-215 EISSN 2392-2192 An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T. S. Eliot as a Major Modernist Ensieh Shabanirad1,*, Ronak Ahmady Ahangar2 1Department of English Language and Literature, University of Tehran, Iran 2Department of English Language and Literature, University of Semnan, Iran *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT As a poet, Eliot seems obsessed with time: the speaker of "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" keeps worrying about being late, and the passage of time in general as he gets older seems to continuously haunt him. In "The Waste Land" we have another form of obsession that presents itself in form of intertexuality; the many narrators of the poem go back and forth in time and provide almost random recollections of the past or haphazard bits of literary texts that are equally concerned with time. This article aims to look deeper into the importance of the concept time in Eliot's poetry, the two poems already mentioned as well as "Four Quartets" (in which a whole section is devoted to time and its philosophy) and then take the important works of other key figures of Modernism and the movement's characteristics into comparison in order to determine whether Eliot's seeming obsession is a fruit of its era or a personal motif of the poet. Keywords: T. S. Eliot; Concept of Time; Intertextuality; Modernist Poetry 1. INTRODUCTION T. S. Eliot is the well known leading figure of the Modernism movement and winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1948. -

Depictions of the Korean War: Picasso to North Korean Propaganda

Depictions of the Korean War: Picasso to North Korean Propaganda Spanning from the early to mid-twentieth century, Korea was subject to the colonial rule of Japan. Following the defeat of the Axis powers in the Second World War, Korea was liberated from the colonial era that racked its people for thirty-five-years (“Massacre at Nogun-ri"). In Japan’s place, the United States and the Soviet Union moved in and occupied, respectively, the South and North Korean territories, which were divided along an arbitrary boundary at the 38th parallel (Williams). The world’s superpowers similarly divided defeated Germany and the United States would go on to promote a two-state solution in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The divisions of Korea and Germany, results of the ideological clash between the democratic United States and the communist Soviet Union, set the stage for the ensuing Cold War. On the 25th of June in 1950, North Korean forces, with support from the Soviet Union, invaded South Korea, initiating the Korean, or “Forgotten,” War. Warfare continued until 1953, when an armistice was signed between Chinese and North Korean military commanders and the U.S.-led United Nations Command (Williams). Notably, South Korea was not a signatory of the armistice; South Korea’s exclusion highlights the unusual circumstance that the people of Korea, a people with a shared history, were divided by the United States and the Soviet Union and incited by the super powers to fight amongst themselves in a proxy war between democracy and communism (Young-na Kim). Though depictions of the Korean War are inextricably tied to the political and social ideologies that launched the peninsula into conflict, no matter an artist’s background, his work imparts upon the viewer the indiscriminate ruination the war brought to the people of Korea. -

New York University

New York University Spring 2020 CORE-UA 761 EXPRESSIVE CULTURES LA BELLE ÉPOQUE: PAINTING, MUSIC AND LITERATURE IN FRANCE 1852-1914 TUESDAY, THURSDAY 11-12.15 Cantor 101 Professor Thomas Ertman ([email protected]) This course takes as its subject the Belle Époque, that period in the life of France’s pre-World War I Third Republic (1871-1914) associated with extraordinary artistic achievement, as well as the Second Empire (1851-1871) that preceded it. Not only was Paris during this time the undisputed western capital of painting and sculpture, it also was the most important production site for new works of musical theater and, arguably, literature as well. It was during these decades that Impressionism launched its assault on the academic establishment, only to be superseded itself by an ever-changing avant-garde associated first with the Nabis, then with fauvism and cubism; that the operas of Bizet, Saint-Saëns and Massenet and the plays of Sardou and Rostand filled the world’s theaters; and that the novels of Zola and stories of Maupassant were translated into dozens of languages. Finally, this was the society that gave birth to one of the greatest literary works of all time, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the first volume of which appeared just as World War I was about to bring the Belle Époque to a violent end. In this course, we will attempt to gain a deeper understanding of the artistic works of this era by placing them in the context of the society within which they were produced, France’s Second Empire and Third Republic. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

KOREA TODAY No. 1, 2017 51 Happy New Year

KOREA TODAY No. 1, 2017 51 Happy New Year EAR READERS, into favourable conditions. D Greeting in the new year 2017, the Korea Having opened the door to 2016 with the inaugu- Today editorial board extends congratulations to all ration of the Sci-Tech Complex, they built a lot of our readers. model, standard factories befitting the era of the Last year we Korea Today staff did all we could to knowledge-driven economy in various parts of the give wide-ranging information about the reality of country by making the most of science and technology the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the principle of self-development first. and to promote the relations of friendship and The Korean youth erected the barrage of the co-operation with the peoples of all countries who Paektusan Hero Youth Power Station in a short span are advancing along the road of independence and of time even in the rigorous natural conditions, and peace. displayed once again their might as masters of the Last year was a proud one of victory and glory for youth power on the occasion of the Ninth Congress of the Korean people. They elected Kim Jong Un Kim Il Sung Socialist Youth League. Chairman of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) and Amidst the fervent enthusiasm for sporting ac- Chairman of the State Affairs Commission of the tivities sweeping the whole country, the Korean Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and pushed sportspeople exalted the honour of their country by ahead with the building of a socialist power under winning gold medals in international competitions.