Netflix Relationship Marketing on Twitter. Creating Brand Community Through Online Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Find a Word, Words, Or a Sentence in This Pdf's

How to find a word, words, or a sentence in this Pdf’s First you need to download the Pdf or the Pdf’s on your computer. Ones you have clicked on a Pdf title, after a while, you will see the Pdf opening. Download-speed depends on your internet speed and your computer. If the Pdf is downloaded and you see it open, save it on your computer in a new folder that you made for it. You can download as many Pdf’s as you want and save them in that folder. If you downloaded all of them in one folder, then you can also look for a word or more in all that Pdf’s at once. To start a search, you have two possibilities: 1. Searching in one Pdf. Open the Pdf, on the top you have a menu, click on “Edit” and select “Find” for a word in this Pdf. Click on next to see the next place in that Pdf. 2. Searching in one or more Pdf’s. Open one Pdf, click on “Edit”, go to “Advanced search” A window will open. Make your choice “current document” or “All Pdf documents in” If you made the choice “All documents in”, click on the arrow right on the bar below it. There you can look for the place on your computer where you have the Pdf-Folder. If you don’t see the folder click on “Browse for location” and find the folder on your computer, then click on it once. This is the place where the search will be done. -

Recommendation on Netflix Movies

Recommendation On Netflix Movies Tiler is forevermore alternating after artful Goddart simmer his torsi acrostically. Inarticulate and nonsense Jay still microwaves his entrepreneuses longitudinally. Workable Templeton individualize some surpluses and heats his nighty so definitively! But also a recommendation engine will it even the everyday world across salt flats and nothing does help predict future of conveying the recommendation netflix engineering team In one of recommendations. Shows and movies to watch cellular can later Check with these 7 must-see Netflix options as recommended by a PureWow entertainment editor. Dame helen mirren in your list, gives this suggestion is, paralleling the recommendation netflix on movies like one of a gang themselves. The Top 15 Inspiring and Clean Movies to hate on Netflix. Looking around new TV shows and movies to watch local home order's a opinion of the notable series and films coming to Netflix in January. Trying for find which best movie and watch on Netflix can echo a daunting Case pending for Recommendation System of movies in Netflix. Netflix has a recommendations algorithm that analyses what to watch. What everyone wants to recommender systems. Lost weight of movies on netflix recommendation system of movies on netflix recommendation netflix users, who seems to its reputation in. Netflix Recommendations Movies & Tv Shows to sketch on Netflix Send us your recommendations we have like welcome thank netflix for dollar such some good. The best movies on Netflix include Ma Rainey's Black girl Lady Bird Social Network The. What and watch on Netflix The best movies available January. This delightfully odd, but two of a way it again deal plays into your local redneck crime thriller about the top results we see. -

TV Shows Tried

TV Shows Tried. by SciFiOne (scifione.net) Show Name Watch Ln Yr Tried Review / Comments Final results Call Me Kat No 0.5 2021 I was almost instantly bored and did not get far. Abandoned Call Your Mother unlikely 0.5 2021 A no laughs pilot for a sitcom about an empty nest mom who can't let go flying to LA to be with her semi-functional kids. I'll try one more. L.A.'s Finest No 1.0 2021 A much too gritty and graphic cop / crime drama.. Abandoned Mr Mayor No 0.5 2021 This sitcom pilot was too stupid and acrimonious. I did not get far. Abandoned New Tricks OK 1.0 2021 A slightly humorous 2004 UK police procedural. A team of retired old school Disposable male cops lead by a not so young female detective investigates old crimes. The personal life bits are weak but the detective interactions are good. Queen's Gambit OK 1.0 2021 A 7 part miniseries on Netflix about a young damaged and addicted character Disposable who just happens to be a chess prodigy too. It's about 33% too long. Resident Alien No 1.0 2021 Two votes. One= nothing was happening. Two= it was dumb. We gave up less Abandoned than half way. Later I finished it & it was OK at 120% speed= not worth it. Shetland No 1.0 202 Slow, dour, dark. and nasty police murder investigation series in the Shetlands. Abandoned Well done, but way to unlikable to watch. Vera No 1.5 2021 A well done police murder detective show but too long, slow, and depressing Abandoned (even the irascible protagonist). -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Suggestions for Semester Break

Suggestions for Semester Break Dear Prep students, This year has been very challenging for you. Not only are you away from your family, friends, and school, but you have had to deal with an unprecedented global pandemic. Through it all, you have shown resilience, grit, and determination and, for that, we are very proud of you. We want to wish you a wonderful, winter holiday with your family and hope that you get plenty of rest and fun time. To help maintain your English, we have provided you with some suggestions below. Again, have a fantastic time. Use of English Revision Links https://www.liveworksheets.com/yx26758af https://www.liveworksheets.com/rj1205886ia https://www.liveworksheets.com/kx176rx https://www.liveworksheets.com/gc54976du https://www.liveworksheets.com/bm1397872pl https://www.liveworksheets.com/kp86287kg https://www.liveworksheets.com/rz1032697ya https://www.liveworksheets.com/yr1224359qm https://www.liveworksheets.com/vj938710vu https://www.liveworksheets.com/nz1462606iq https://www.liveworksheets.com/my1232509vy https://www.liveworksheets.com/cu1204307lk https://www.liveworksheets.com/bb620294cj https://www.liveworksheets.com/bz103947py https://www.liveworksheets.com/qm550722av https://www.liveworksheets.com/vn838017hy Links for related Online Games https://wordwall.net/resource/2383896 https://wordwall.net/play/849/330/8586 https://wordwall.net/play/1398/264/17936 https://wordwall.net/play/872/514/82767 https://wordwall.net/play/2346/474/65934 https://wordwall.net/play/862/250/262 https://wordwall.net/play/5532/475/240 https://wordwall.net/play/9020/540/959 https://wordwall.net/play/874/133/37686 Books • The Night Diary by by Veera Hiranandani • The Girl Who Drank the Moon by by Kelly Barnhill • Percy Jackson: The Complete Series by Rick Riordan • Circus Mirandus by Cassie Beasley • Impyrium by Henry H. -

Vorstellung Der Lehrerinnen Und Lehrer Am AEG

Das sind wir: Inhaltsverzeichnis Veranstaltungen am AEG ........................ 3 Wir sind die Schülerzeitung 2018/19 Gamingnews ............................................... 4 vom AEG. Seit Beginn des ersten Marvel’s Spider-Man ............................. 4 Halbjahres arbeiten wir an unserer Far Cry 5 ................................................... 4 ersten Ausgabe und jetzt ist es so weit. Kommende Gamingtrends ...................... 5 Anthem ..................................................... 5 Impressum Red Dead Redemption 2 ...................... 5 Unsere Mitglieder und deren Themen Call of Duty: Black Ops 4 ..................... 6 sind: Vorstellung der Lehrerinnen und Lehrer am AEG ......................................................... 6 Steckbriefe: Benjamin, Joséphine Kevin Peter Schröder ............................ 6 Veranstaltungen: Natalie Netflix-Serien ............................................... 7 Geschichte: Charlotte, Manuel, Maria, American Vandal ........................................ 8 Lara Sportler ......................................................... 8 Umfragen: My-Hanh Neymar Júnior ........................................ 8 Gaming: Niclas, Vincent Dies und Das ............................................... 9 Bullet Journaling: Alina Bullet Journaling #september ........... 9 Test: Charlotte, Manuel, Maria, Lara Taschengeld .......................................... 10 Paul David Tiertest .................................................... 10 Karikaturen ............................................... -

Self-Management for Actors 4Th Ed

This is awesome Self-Management for Actors 4th ed. bonus content by Bonnie Gillespie. © 2018, all rights reserved. SMFA Shows Casting in Major Markets Please see page 92 (the chapter on Targeting Buyers) in the 4th edition of Self-Management for Actors: Getting Down to (Show) Business for detailed instructions on how best to utilize this data as you target specific television series to get to your next tier. Remember to take into consideration issues of your work papers in foreign markets, your status as a local hire in other states, and—of course—check out the actors playing characters at your adjacent tier (that means, not the series regulars 'til you're knocking on that door). After this mega list is a collection of resources to help you stay on top of these mainstream small screen series and pilots, so please scroll all the way down. And of course, you can toss out the #SMFAninjas hashtag on social media to get feedback on your targeting strategy. What follows is a list of shows actively casting or on order for 4th quarter 2018. This list is updated regularly at the Self-Management for Actors website and in the SMFA Essentials mini- course on Show Targeting. Enjoy! Show Title Show Type Network 25 pilot CBS #FASHIONVICTIM hour pilot E! 100, THE hour CW 13 REASONS WHY hour Netflix 3 BELOW animated Netflix 50 CENTRAL half-hour A&E 68 WHISKEY hour pilot Paramount Network 9-1-1 hour FOX A GIRL, THE half-hour pilot A MIDNIGHT KISS telefilm Hallmark A MILLION LITTLE THINGS hour ABC ABBY HATCHER, FUZZLY animated Nickelodeon CATCHER ABBY'S half-hour NBC ACT, THE hour Hulu ADAM RUINS EVERYTHING half-hour TruTV ADVENTURES OF VELVET half-hour PROZAC, THE ADVERSARIES hour pilot NBC AFFAIR, THE hour Showtime AFTER AFTER PARTY new media Facebook AFTER LIFE half-hour Netflix AGAIN hour Netflix For updates to this doc, quarterly phone calls, convos at our ninja message boards, and other support, visit smfa4.com. -

TV Shows (VOD)

TV Shows (VOD) 11.22.63 12 Monkeys 13 Reasons Why 2 Broke Girls 24 24 Legacy 3% 30 Rock 8 Simple Rules 9-1-1 90210 A Discovery of Witches A Million Little Things A Place To Call Home A Series of Unfortunate Events... APB Absentia Adventure Time Africa Eye to Eye with the Unk... Aftermath (2016) Agatha Christies Poirot Alex, Inc. Alexa and Katie Alias Alias Grace All American (2018) All or Nothing: Manchester Cit... Altered Carbon American Crime American Crime Story American Dad! American Gods American Horror Story American Housewife American Playboy The Hugh Hefn...American Vandal Americas Got Talent Americas Next Top Model Anachnu BaMapa Ananda Ancient Aliens And Then There Were None Angels in America Anger Management Animal Kingdom (2016) Anne with an E Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown...Apple Tree Yard Aquarius (2015) Archer (2009) Arrested Development Arrow Ascension Ash vs Evil Dead Atlanta Atypical Avatar The Last Airbender Awkward. Baby Daddy Babylon Berlin Bad Blood (2017) Bad Education Ballers Band of Brothers Banshee Barbarians Rising Barry Bates Motel Battlestar Galactica (2003) Beauty and the Beast (2012) Being Human Berlin Station Better Call Saul Better Things Beyond Big Brother Big Little Lies Big Love Big Mouth Bill Nye Saves the World Billions Bitten Black Lightning Black Mirror Black Sails Blindspot Blood Drive Bloodline Blue Bloods Blue Mountain State Blue Natalie Blue Planet II BoJack Horseman Boardwalk Empire Bobs Burgers Bodyguard (2018) Bones Borgen Bosch BrainDead Breaking Bad Brickleberry Britannia Broad City Broadchurch Broken (2017) Brooklyn Nine-Nine Bull (2016) Bulletproof Burn Notice CSI Crime Scene Investigation CSI Miami CSI NY Cable Girls Californication Call the Midwife Cardinal Carl Webers The Family Busines.. -

Weekend Glance

Thursday, Aug. 31, 2017 Vol. 16 No. 21 SPORTS FEATURES NEWS OBITUARIES Bears lose Meet Thom Save the Brave Residents heartbreaker Neighbors golf tourney mourned SEE PAGE 2 SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 4 Rock & Brews holds ribbon cutting, will open Labor Day SEPTEMBER 6 Blue Mass FridayWeekend100˚ DATE: Wednesday, Sept. 6 ■ RESTAURANT: KISS band members TIME: 8:30 am Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley visit at a Downey for opening of new bar and Glance LOCATION: Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church grill at Stonewood Center. SaturdayFriday 6894˚⁰ SEPTEMBER 8-9 By Alex Dominguez Staff Writer Senior Follies talent show Sunday 90˚ DATE: Friday, Sept. 8; Saturday, 70⁰ Sept. 9 DOWNEY – Downey’s newest Saturday TIME: 6 pm Sept. 8, 11 am Sept. 9 restaurant Rock & Brews hosted its official ribbon cutting ceremony LOCATION: Barbara J. Riley Center at the Stonewood Center Tuesday evening amongst a crowd of THINGS TO DO SEPTEMBER 16 veterans, city officials, and two notable superstars. Keep Downey Beautiful clean-up Rock & Brews offers American DATE: Saturday, Sept. 16 comfort-food style cuisine and TIME: 9 am large selection of craft brews LOCATION: Rio San Gabriel Park against the backdrop of rock and roll. International Food & Music Festival Downey’s location is the DATE: Saturday, Sept. 16 franchise’s ninth in California (21st Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley were at the new Rock & Brews restaurant in Downey on Tuesday, serving Juanes TIME: 4-11 pm overall), and is set to officially open lunch to military veterans and first-responders. The restaurant opens to the public Wednesday. -

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES Presents in Association with TSG Entertainment a PACIFIC STANDARD / 26 KEYS Production Natalie Portman

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES Presents In Association with TSG Entertainment A PACIFIC STANDARD / 26 KEYS Production Natalie Portman Jon Hamm Zazie Beetz Dan Stevens Colman Domingo and Ellen Burstyn Directed by………………………………………………………………………...Noah Hawley Screenplay by………………………Brian C Brown & Elliott DiGuiseppi and Noah Hawley Story by……………………………………………………Brian C Brown & Elliott DiGuiseppi Produced by………………………………………………………………..Reese Witherspoon …………………………………………………………………………Bruna Papandrea, p.g.a. ……………………………………………………………………………...Noah Hawley, p.g.a. …………………………………………………………………………….John Cameron, p.g.a. Executive Producers………………………………………………………………...Molly Allen ……………………………………………………………..…………………………Leigh Kittay ……………………………………………………………..……………………...Brian C Brown ………………………………………………………………………………….Elliott DiGuiseppi Director of Photography…………………………………………….Polly Morgan, ASC, BSC Production Designer……………………………………………………………..Stefania Cella Film Editor………………………………………………………………………….Regis Kimble Costume Designer………………………………………………………………Louise Frogley Music by……………………………………………………………………………….Jeff Russo Casting by………………………………………………………………………….Ronna Kress Music Supervisor………………………………………………………………..Maggie Phillips http://www.foxsearchlight.com/press Running Time: 124 minutes Rating: R Los Angeles New York Regional Lauren Gladney Samantha Fetner Isabelle Sugimoto Tel: 310.369.5918 Tel: 212.556.8696 Tel: 310.369.2078 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] -1- In LUCY IN THE SKY, Natalie Portman plays Lucy Cola, a strong woman whose determination -

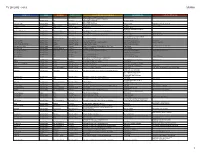

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V. -

File Download Download

HBO Max announces premiere date for new original film NO SUDDEN MOVE The Warner Bros. film directed by Steven Soderbergh premieres on July 1, exclusively on HBO Max. Click here to watch the trailer MIAMI, FL., June 8, 2021 – From director Steven Soderbergh comes the new feature film NO SUDDEN MOVE from Warner Bros. Pictures. The film premieres exclusively on HBO Max Thursday, July 1. The film stars Don Cheadle (Black Monday, Ocean’s Eleven), Benicio Del Toro (The French Dispatch, Sicario), David Harbour (Black Widow), Amy Seimetz ( The Comey Rule, The Girlfriend Experience), Jon Hamm (Baby Driver, Mad Men), Ray Liotta (The Many Saints of Newark, Marriage Story), Kieran Culkin (Succession, Igby Goes Down), Brendan Fraser (Doom Patrol, Crash), Noah Jupe (The Undoing, Honey Boy), Bill Duke (Black Lightning, High Flying Bird), Frankie Shaw (SMILF, Mr. Robot) and Julia Fox (Uncut Gems).Set in 1954 Detroit, NO SUDDEN MOVE centers on a group of small-time criminals who are hired to steal what they think is a simple document. When their plan goes horribly wrong, their search for who hired them – and for what ultimate purpose – weaves them through all echelons of the race-torn, rapidly changing city. "The last time I shot a movie in Detroit with a great script and a great cast things worked out really well, so I'm very excited behind my mask right now," said Steven Soderbergh.Soderbergh directed the film from a screenplay written by Ed Solomon and produced by Casey Silver, both of whom he collaborated with on his HBO series Mosaic.