Raymond Hickey the Languages of Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2 Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Sabine Asmus, Barbara Braid and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5700-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5700-0 CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................. vii Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept of Unity in Diversity Sabine Asmus Part I: Cultural Markers Chapter One ................................................................................................ 3 Questions of Identity in Contemporary Ireland and Spain Cormac Anderson Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 27 Scottish Whisky Revisited Uwe Zagratzki Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 39 Welsh -

Notes on the Development of the Linguistic Society of America 1924 To

NOTES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LINGUISTIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA 1924 TO 1950 MARTIN JOOS for JENNIE MAE JOOS FORE\\ORO It is important for the reader of this document to know how it came to be written and what function it is intended to serve. In the early 1970s, when the Executive Committee and the Committee on Pub1ications of the linguistic Society of America v.ere planning for the observance of its Golden Anniversary, they decided to sponsor the preparation of a history of the Society's first fifty years, to be published as part of the celebration. The task was entrusted to the three living Secretaries, J M. Cowan{who had served from 1940 to 1950), Archibald A. Hill {1951-1969), and Thomas A. Sebeok {1970-1973). Each was asked to survey the period of his tenure; in addition, Cowan,who had learned the craft of the office from the Society's first Secretary, Roland G. Kent {deceased 1952),was to cover Kent's period of service. At the time, CO'flal'\was just embarking on a new career. He therefore asked his close friend Martin Joos to take on his share of the task, and to that end gave Joos all his files. Joos then did the bulk of the research and writing, but the~ conferred repeatedly, Cowansupplying information to which Joos v.t>uldnot otherwise have had access. Joos and HiU completed their assignments in time for the planned publication, but Sebeok, burdened with other responsibilities, was unable to do so. Since the Society did not wish to bring out an incomplete history, the project was suspended. -

A Linguistic and Anthropological Approach to Isingqumo, South Africa’S Gay Black Language

“WHERE THERE’S GAYS, THERE’S ISINGQUMO”: A LINGUISTIC AND ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH TO ISINGQUMO, SOUTH AFRICA’S GAY BLACK LANGUAGE Word count: 25 081 Jan Raeymaekers Student number: 01607927 Supervisor(s): Prof. Dr. Maud Devos, Prof. Dr. Hugo DeBlock A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies Academic year: 2019 - 2020 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Theoretical Framework ....................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Lavender Languages...................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1. What are Lavender Languages? ....................................................................... 8 2.1.2. How Are Languages Categorized? ................................................................ 12 2.1.3. Documenting Undocumented Languages ................................................. 17 2.2. Case Study: IsiNgqumo .............................................................................................. 18 2.2.1. Homosexuality in the African Community ................................................ 18 2.2.2. Homosexuality in the IsiNgqumo Community -

The$Irish$Language$And$Everyday$Life$ In#Derry!

The$Irish$language$and$everyday$life$ in#Derry! ! ! ! Rosa!Siobhan!O’Neill! ! A!thesis!submitted!in!partial!fulfilment!of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of! Doctor!of!Philosophy! The!University!of!Sheffield! Faculty!of!Social!Science! Department!of!Sociological!Studies! May!2019! ! ! i" " Abstract! This!thesis!explores!the!use!of!the!Irish!language!in!everyday!life!in!Derry!city.!I!argue!that! representations!of!the!Irish!language!in!media,!politics!and!academic!research!have! tended!to!overKidentify!it!with!social!division!and!antagonistic!cultures!or!identities,!and! have!drawn!too!heavily!on!political!rhetoric!and!a!priori!assumptions!about!language,! culture!and!groups!in!Northern!Ireland.!I!suggest!that!if!we!instead!look!at!the!mundane! and!the!everyday!moments!of!individual!lives,!and!listen!to!the!voices!of!those!who!are! rarely!heard!in!political!or!media!debate,!a!different!story!of!the!Irish!language!emerges.! Drawing!on!eighteen!months!of!ethnographic!research,!together!with!document!analysis! and!investigation!of!historical!statistics!and!other!secondary!data!sources,!I!argue!that! learning,!speaking,!using,!experiencing!and!relating!to!the!Irish!language!is!both!emotional! and!habitual.!It!is!intertwined!with!understandings!of!family,!memory,!history!and! community!that!cannot!be!reduced!to!simple!narratives!of!political!difference!and! constitutional!aspirations,!or!of!identity!as!emerging!from!conflict.!The!Irish!language!is! bound!up!in!everyday!experiences!of!fun,!interest,!achievement,!and!the!quotidian!ebbs! and!flows!of!daily!life,!of!getting!the!kids!to!school,!going!to!work,!having!a!social!life!and! -

Corpas Na Gaeilge (1882-1926): Integrating Historical and Modern

Corpas na Gaeilge (1882-1926): Integrating Historical and Modern Irish Texts Elaine Uí Dhonnchadha3, Kevin Scannell7, Ruairí Ó hUiginn2, Eilís Ní Mhearraí1, Máire Nic Mhaoláin1, Brian Ó Raghallaigh4, Gregory Toner5, Séamus Mac Mathúna6, Déirdre D’Auria1, Eithne Ní Ghallchobhair1, Niall O’Leary1 1Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, Ireland 2National University of Ireland Maynooth, Ireland 3Trinity College Dublin, Ireland 4Dublin City University, Ireland 5Queens University Belfast, Northern Ireland 6University of Ulster, Northern Ireland 7Saint Louis University, Missouri, USA E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the processing of a corpus of seven million words of Irish texts from the period 1882-1926. The texts which have been captured by typing or optical character recognition are processed for the purpose of lexicography. Firstly, all historical and dialectal word forms are annotated with their modern standard equivalents using software developed for this purpose. Then, using the modern standard annotations, the texts are processed using an existing finite-state morphological analyser and part-of-speech tagger. This method enables us to retain the original historical text, and at the same time have full corpus-searching capabilities using modern lemmas and inflected forms (one can also use the historical forms). It also makes use of existing NLP tools for modern Irish, and enables integration of historical and modern Irish corpora. Keywords: historical corpus, normalisation, standardisation, natural language processing, Irish, Gaeilge 1. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Cultural Exchange: from Medieval

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 1: Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: from Medieval to Modernity AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: Medieval to Modern Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative and The Stout Research Centre Irish-Scottish Studies Programme Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 1753-2396 Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Issue Editor: Cairns Craig Associate Editors: Stephen Dornan, Michael Gardiner, Rosalyn Trigger Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Michael Brown, University of Aberdeen Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Brad Patterson, Victoria University of Wellington Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal, published twice yearly in September and March, by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. An electronic reviews section is available on the AHRC Centre’s website: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrc- centre.shtml Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be addressed to The Editors,Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, Humanity Manse, 19 College Bounds, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UG or emailed to [email protected] Subscriptions and business correspondence should be address to The Administrator. -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

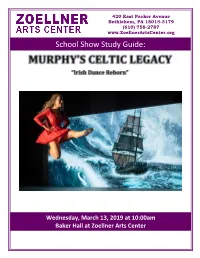

School Show Study Guide

420 East Packer Avenue Bethlehem, PA 18015-3179 (610) 758-2787 www.ZoellnerArtsCenter.org School Show Study Guide: Wednesday, March 13, 2019 at 10:00am Baker Hall at Zoellner Arts Center USING THIS STUDY GUIDE Dear Educator, On Wednesday, March 13, your class will attend a performance by Murphy’s Celtic Legacy, at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center in Baker Hall. You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Zoellner Arts Center field trip. Materials in this guide include information about the performance, what you need to know about coming to a show at Zoellner Arts Center and interesting and engaging activities to use in your classroom prior to and following the performance. These activities are designed to go beyond the performance and connect the arts to other disciplines and skills including: Dance Culture Expression Social Sciences Teamwork Choreography Before attending the performance, we encourage you to: Review the Know before You Go items on page 3 and Terms to Know on pages 9. Learn About the Show on pages 4. Help your students understand Ireland on pages 11, the Irish dance on pages 17 and St. Patrick’s Day on pages 23. Engage your class the activity on pages 25. At the performance, we encourage you to: Encourage your students to stay focused on the performance. Encourage your students to make connections with what they already know about rhythm, music, and Irish culture. Ask students to observe how various show components, like costumes, lights, and sound impact their experience at the theatre. After the show, we encourage you to: Look through this study guide for activities, resources and integrated projects to use in your classroom. -

Preservation of Original Orthography in the Construction of an Old Irish Corpus

Preservation of Original Orthography in the Construction of an Old Irish Corpus. Adrian Doyle, John P. McCrae, Clodagh Downey National University of Ireland Galway [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Irish was one of the earliest vernacular European languages to have been written using the Latin alphabet. Furthermore, there exists a relatively large corpus of Irish language text dating to this Old Irish period (c. 700 – c 950). Beginning around the turn of the twentieth century, a large amount of study into Old Irish revealed a highly standardised language with a rich morphology, and often creative orthography. While Modern Irish enjoys recognition from the Irish state as the first official language, and from the EU as a full official and working language, Old Irish is almost incomprehensible to most modern speakers, and remains extremely under-resourced. This paper will examine considerations which must be given to aspects of orthography and palaeography before the text of a historical manuscript can be represented in digital format. Based on these considerations the argument will be presented that digitising the text of the Würzburg glosses as it appears in Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus will enable the use of computational analysis to aid in current areas of linguistic research by preserving original orthographical information. The process of compiling the digital corpus, including considerations given to preservation of orthographic information during this process, will then be detailed. Keywords: manuscripts, palaeography, orthography, digitisation, optical character recognition, Python, Unicode, morphology, Old Irish, historical languages glosses]” (2006, p.10). Before any text can be deemed 1. -

1. Provide an Introduction and Overview of Your Study Abroad Experience

1. Provide an introduction and overview of your study abroad experience. I received the wonderful and unique experience of studying abroad at the University of Limerick Ireland, and upon my journey; I met new friends from all over the world, gained insight into not only the culture of Ireland, but also cultures from around the world, and discovered my true independence and strength. I joined the Outdoor Pursuits club and the International Society at the University of Limerick and these clubs aided in my friendship making and advanced cultural knowledge. Through these clubs, I was able to travel around Ireland not only to the cities, but also to the farmland and the country side as I hiked through mountains and valleys. Studying abroad in Ireland was a fantastic and educational experience. 2. Using one to two examples, explain how your study abroad experience advanced your knowledge and understanding of the world’s diverse cultures, environments, practices and/or values. Through my curiosity of culture and people and the incredible friends I made, I learned about not only the Irish culture, but also was able to gain some knowledge of Grecian, German, French, Spanish, and Swedish cultures. My closest friends were from these various countries and allowed me to ask them about the different aspects of their cultures and lives back at their home. During my time in Ireland, I was also able to stay a full week with an Irish family when my father came to visit. Through them I discovered many Irish ways and culture. I was able to make a true Irish breakfast with them as well as attend an Irish church, which is a big cultural thing for Irish families. -

Language Education Policy Profile IRELAND

Language Education Policy Profile IRELAND Language Policy Division Strasbourg Department of Education and Science Ireland 2005 - 2007 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................5 1.1. The origins, context and purpose of the Profile................................................................................5 1.2. Council of Europe policies ..................................................................................................................6 1.3. Irish priorities and key issues in the review of language teaching..................................................8 1.3.1. National Language Policy and Societal Attitudes.......................................................................8 1.3.2. The Irish Language in Society and in Education .......................................................................8 1.3.3. Language as a Resource................................................................................................................8 1.3.4. National Policy and European Policy ..........................................................................................8 1.3.5. The Changing Sociolinguistic Map of Ireland ............................................................................8 1.3.6. An Integrated Approach to Language Teaching........................................................................9 1.3.7. The Future of Modern Foreign Languages in Primary School.................................................9 1.3.8. Assessment -

Download (4MB)

Grinnstaidéar ar an nGaol Gabhlánach: Anailís Shochstairiúil ar Nádúr an Dátheangachais Shochaíoch in Éirinn le linn an Fichiú hAois Gráinne Ní Bhreithiún Tá an tráchtas seo á chur faoi bhráid Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad don chéim dochtúireachta ag Gráinne Ní Bhreithiún, B.A. Scoil an Léinn Cheiltigh, Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad, Co. Chill Dara, Éire. Stiúrthóir: An Dr Tadhg Ó Dúshláine Roinn na Nua-Ghaeilge Ollamh na Nua-Ghaeilge: An tOll. Ruairí Ó hUiginn Aibreán 2014 Imleabhar 2/2 Clár an Ábhair Liosta na dTáblaí i Liosta na Léaráidí ii !! "#$%$&$'(#()*#+,-.(/0123$-,*($(45$167(869$&*(:#(;*#:<#(========================(>! 7.1! Réamhrá(========================================================================================================================(>! 7.2! Creatlach UNESCO(====================================================================================================(?! 7.3! Tabhairt Isteach na Gaeilge i Réimsí Nua Úsáide(=============================================(>@! 7.4! Tátal(=============================================================================================================================(A?! @! "#$%$&$'(#(,B+,-.(CD*#<#$D-(&0(45$167(#<36(&0(E,*9$:(F3#(================(AG! 8.1! Réamhrá(======================================================================================================================(AG! 8.2! Creatlach UNESCO(==================================================================================================(AG! 8.3! Réimse na hOibre(======================================================================================================(?>!