Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary FEIS and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics Lake Michigan is a dynamic deepwater oligotrophic ecosystem that supports a diverse mix of native and non-native species. Although the watershed, wetlands, and tributaries that drain into the open waters are comprised of a wide variety of habitat types critical to supporting its diverse biological community this section will focus on the open water component of this system. Watershed, wetland, and tributaries issues will be addressed in the Northeastern Morainal Natural Division section. Species diversity, as well as their abundance and distribution, are influenced by a combination of biotic and abiotic factors that define a variety of open water habitat types. Key abiotic factors are depth, temperature, currents, and substrate. Biotic activities, such as increased water clarity associated with zebra mussel filtering activity, also are critical components. Nearshore areas support a diverse fish fauna in which yellow perch, rockbass and smallmouth bass are the more commonly found species in Illinois waters. Largemouth bass, rockbass, and yellow perch are commonly found within boat harbors. A predator-prey complex consisting of five salmonid species and primarily alewives populate the pelagic zone while bloater chubs, sculpin species, and burbot populate the deepwater benthic zone. Challenges Invasive species, substrate loss, and changes in current flow patterns are factors that affect open water habitat. Construction of revetments, groins, and landfills has significantly altered the Illinois shoreline resulting in an immeasurable loss of spawning and nursery habitat. Sea lampreys and alewives were significant factors leading to the demise of lake trout and other native species by the early 1960s. -

Physical Limnology of Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron

PHYSICAL LIMNOLOGY OF SAGINAW BAY, LAKE HURON ALFRED M. BEETON U. S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory Ann Arbor, Michigan STANFORD H. SMITH U. S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory Ann Arbor, Michigan and FRANK H. HOOPER Institute for Fisheries Research Michigan Department of Conservation Ann Arbor, Michigan GREAT LAKES FISHERY COMMISSION 1451 GREEN ROAD ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN SEPTEMBER, 1967 PHYSICAL LIMNOLOGY OF SAGINAW BAY, LAKE HURON1 Alfred M. Beeton, 2 Stanford H. Smith, and Frank F. Hooper3 ABSTRACT Water temperature and the distribution of various chemicals measured during surveys from June 7 to October 30, 1956, reflect a highly variable and rapidly changing circulation in Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron. The circula- tion is influenced strongly by local winds and by the stronger circulation of Lake Huron which frequently causes injections of lake water to the inner extremity of the bay. The circulation patterns determined at six times during 1956 reflect the general characteristics of a marine estuary of the northern hemisphere. The prevailing circulation was counterclockwise; the higher concentrations of solutes from the Saginaw River tended to flow and enter Lake Huron along the south shore; water from Lake Huron entered the northeast section of the bay and had a dominant influence on the water along the north shore of the bay. The concentrations of major ions varied little with depth, but a decrease from the inner bay toward Lake Huron reflected the dilution of Saginaw River water as it moved out of the bay. Concentrations in the outer bay were not much greater than in Lake Huronproper. -

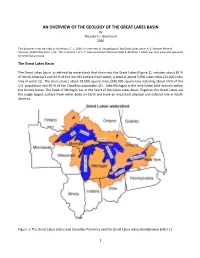

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

Saginaw River/Bay Fish & Wildlife Habitat BUI Removal Documentation

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION 5 77 WEST JACKSON BOULEVARD CHICAGO, IL 60604-3590 6 MAY 2014 REPLY TO THE ATTENTION OF Mr. Roger Eberhardt Acting Deputy Director, Office of the Great Lakes Michigan Department of Environmental Quality 525 West Allegan P.O. Box 30473 Lansing, Michigan 48909-7773 Dear Roger: Thank you for your February 6, 2014, request to remove the "Loss of Fish and Wildlife Habitat" Beneficial Use Impairment (BUI) from the Saginaw River/Bay Area of Concern (AOC) in Michigan, As you know, we share your desire to restore all of the Great Lakes AOCs and to formally delist them. Based upon a review of your submittal and the supporting data, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency hereby approves your BUI removal request for the Saginaw River/Bay AOC, EPA will notify the International Joint Commission of this significant positive environmental change at this AOC. We congratulate you and your staff, as well as the many federal, state, and local partners who have worked so hard and been instrumental in achieving this important environmental improvement. Removal of this BUI will benefit not only the people who live and work in the Saginaw River/Bay AOC, but all the residents of Michigan and the Great Lakes basin as well. We look forward to the continuation of this important and productive relationship with your agency and the local coordinating committee as we work together to fully restore all of Michigan's AOCs. If you have any further questions, please contact me at (312) 353-4891, or your staff may contact John Perrecone, at (312) 353-1149. -

Herring Gulls, Larus Argentatus, Nesting on Sandusky Bay, Lake Erie, 1989

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service October 1989 Herring Gulls, Larus argentatus, Nesting on Sandusky Bay, Lake Erie, 1989 Richard A. Dolbeer U.S. Department of Agriculture, Denver Wildlife Research Center P.P. Woronecki U.S. Department of Agriculture, Denver Wildlife Research Center T. W. Seamans U.S. Department of Agriculture, Denver Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] B. N. Buckingham Ohio Department of Natural Resources E. C. Cleary U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal Damage Control Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Dolbeer, Richard A.; Woronecki, P.P.; Seamans, T. W.; Buckingham, B. N.; and Cleary, E. C., "Herring Gulls, Larus argentatus, Nesting on Sandusky Bay, Lake Erie, 1989" (1989). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 129. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Herring Gulls, Larus argentatus, Nesting on Sandusky Bay, Lake Erie, 19891 R. A. DOLBEER, P. P. WORONECKI, T. W. SEAMANS, B. N. BUCKINGHAM, AND E. C. CLEARY, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Denver Wildlife Research Center, 6100 Columbus Avenue, Sandusky, OH 44870, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Resthaven Wildlife Area, P. -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

Lighthouses of the Western Great Lakes a Web Site Researched and Compiled by Terry Pepper

A Publication of Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes © 2011, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, P.O. Box 545, Empire, MI 49630 www.friendsofsleepingbear.org [email protected] Learn more about the Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, our mission, projects, and accomplishments on our web site. Support our efforts to keep Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore a wonderful natural and historic place by becoming a member or volunteering for a project that can put your skills to work in the park. This booklet was compiled by Kerry Kelly, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes. Much of the content for this booklet was taken from Seeing the Light – Lighthouses of the Western Great Lakes a web site researched and compiled by Terry Pepper www.terrypepper.com. This web site is a great resource if you want information on other lighthouses. Other sources include research reports and photos from the National Park Service. Information about the Lightships that were stationed in the Manitou Passage was obtained from David K. Petersen, author of Erhardt Peters Volume 4 Loving Leland. http://blackcreekpress.com. Extensive background information about many of the residents of the Manitou Islands including a well- researched piece on the William Burton family, credited as the first permanent resident on South Manitou Island is available from www.ManitouiIlandsArchives.org. Click on the Archives link on the left. 2 Lighthouses draw us to them because of their picturesque architecture and their location on beautiful shores of the oceans and Great Lakes. The lives of the keepers and their families fascinate us as we try to imagine ourselves living an isolated existence on a remote shore and maintaining the light with complete dedication. -

Sandusky Bay Strategic Restoration Plan Sandusky, Ohio

CITY OF SANDUSKY Sandusky Bay Strategic Restoration Plan Sandusky, Ohio A Strategic Implementation Plan prioritizes coastal wetland restoration projects for implementation to maximize water qual- ity enhancement, nutrient and sediment reductions, and fi sh and wildlife habitat improvements. construction, nutrient load- Working closely with the ings, shoreline hardening, and City, Biohabitats is lead- changes in land use practices. ing the 18-month planning In addition, the nutrient load- effort, which will ultimately ings are stimulating harm- yield a portfolio of restora- ful algal blooms. The Bay tion projects through the use has been deemed a priority of Landscape Conservation management area by the Great Collaborative (LCC) and Lakes Fishery Commission Design (LCD) principles. and the Great Lakes Water Collaborating with a broad Quality Agreement. range of stakeholders that in- cludes federal, state, and local andusky Bay encom- With grant funding from agencies within three counties; S passes 64 square miles the Ohio Department of scientists from local academic of open water along the Natural Resources, the institutions; NGOs; practitio- southern shore of Lake Erie City of Sandusky, launched ners; and private sector part- and receives runoff from the Sandusky Bay Strategic ners, Biohabitats is assessing nearly one million acres of Restoration Initiative (SBSRI), and analyzing proposed sites, land. A major commercial and an implementation plan for a setting goals, and prioritizing recreational hub for northern portfolio of projects designed restoration projects to create Ohio, this unique bay ecosys- to enhance the quality of life a strategic restoration imple- tem holds some of the most for the entire region, maxi- mentation plan. -

Mackinac County

MACKINAC COUNTY S o y C h r t o u Rock r u BETTY B DORGANS w C t d 8 Mile R D n 6 mlet h o i C d t H o y G r e e Island LANDING 4 CROSSING B u N a Y o d Rd R R R 4 e 8 Mile e y 4 1 k t R k d n 2 ix d t S 14 7 r i Advance n p n 17 d i m Unknow d o e a F u 5 C 123 t e T 7 x k d y O l a o s e i R i R 1 Ibo Rd 1 r r e r Sugar d C M o d Island R a e d R 4 p y f e D c E e S l e n N e i 4 C r a R E R o Y d R L 221 e v a i l 7 R h d A i w x d N i C n S a e w r d g d p e n s u d p 5 a c o r R a r t e B U d d T Island in t g G i e e a n r i g l R R n i o R a d e e R r Rd d o C C o e d d 9 Mile e c 4 r r g k P r h d a L M e n M t h R v B W R R e s e 2 r R C R O s n p N s l k n RACO ea l e u l 28 o ROSEDALE n i R C C d 1 y C l i ree a e le Rd e k a U d e v i 9 Mi e o S y r S a re e d i n g C R R Seney k t ek N e r h C Shingle Bay o U e i u C s R D r e U essea S Sugar B d e F s h k c n c i MCPHEES R L n o e f a a r s t P x h B y e d ut a k 3 So i r k i f u R e t o 0 n h a O t t 1 3 R r R d r r A h l R LANDING 3 M le 7 7 s i T o 1 E d 0 M n i 1 C w a S t U i w e a o s a kn ECKERMAN t R R r v k C o n I Twp r C B U i s Superior e e Island h d d e b Mile Rd r d d Mile Rd 10 e a S f 10 o e i r r q l n s k i W c h n d C u F 3 Columbus u T l McMillan Twp ens M g C g a h r t E a h r 5 Mo reek R n E T 9 H H q m REXFORD c e i u a DAFTER n R W r a l k 5 o M r v Twp Y m r h m L e e C p e i e Twp F s e STRONGS d i Dafter Twp H ty Road 462 East R t d e a Coun P n e e S n e r e v o v o s l d C i R m s n d T o Twp h R t Chippewa l p R C r e NEWBERRY U o e R a n A -

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan Was Granted

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan was granted statehood on January 26, 1837, Michigan also acquired ownership of the Great Lakes' bottomlands under the equal footing doctrine.1 However before Michigan could become a state, the United States first had to acquire title from us (Ottawa and Chippewa bands) because Anglo-American law acknowledged that we owned legal title as the aboriginal occupants of the territory we occupied. But when we agreed to cede legal title to the United States in the March 28, 1836 Treaty of Washington ("1836 Treaty", 7 Stat. 491), we reserved fishing, hunting and gathering rights. Therefore, Michigan's ownership of both the lands and Great Lakes waters within the cession area of the 1836 Treaty was burdened with preexisting trust obligations with respect to our treaty-reserved resources. First, the public trust doctrine imposes a duty (trust responsibility) upon Michigan to protect the public trust in the resources dependent upon the quality of the Great Lakes water.2 In addition, Art. IV, § 52 of Michigan's Constitution says "conservation…of the natural resources of the state are hereby declared to be of paramount public concern…" and then mandates the legislature to "provide for the protection of the air, water and other natural resources from 3 pollution, impairment and destruction." 1 The State of Michigan acquired title to these bottomlands in its sovereign capacity upon admission to the Union and holds them in trust for the benefit of the people of Michigan. Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Illinois, 146 U.S. 387, 434-35 (1892); Nedtweg v. -

Naming Rationale

Naming Rationale Label-wise, the goal of the map is to illuminate the various landforms of Michigan, of which many residents are quite unaware. It should inform them of existing toponyms, as well as provide new toponyms for noteworthy features which don’t seem to have any. Landform toponyms can be approached from a folk or a technical perspective. A local might refer to the Yellow Hills that lay beside the Green Plain, whereas a physical geographer would recognize the glacial origins of these features and have good reason to call them the Yellow Moraine, next to the Green Glacial Lake Plain. My chosen perspective is folk toponymy. However, for many features in Michigan such names are lacking or poorly-attested, whereas technical names are much more common (experts think about landforms much more than other residents). Therefore I have sometimes borrowed from the list of technical names, modifying them at times to be more folk-like. For some features, the sources I have disagree as to their name or extent. I have done my best to mediate disputes. Other features have names that appear only on a single source, invented by mapmakers who saw landforms languishing in anonymity. I have propagated these names where they seemed sensible to me, and coined some of my own. All toponyms have to start somewhere. The result is a mixture of folk and technical, existing and newly-coined. Another cartographer would, given the same starting materials, produce a different result. I hope though, that my decisions seem justifiable and sound. List of Names and Sources In the pages that follow, I have compiled my notes and sources for every label on the map. -

History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966 - 2003

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966 - 2003 Mike Thomas, Research Biologist (retired) and Todd Wills, Area Station Manager Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Lake St. Clair Great Lakes Station was constructed on a confined dredge disposal site at the mouth of the Clinton River and opened for business in 1974. In this photo, the Great Lakes Station (red roof) is visible in the background behind the lighter colored Macomb County Sheriff Marine Division Office. Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station Website: http://www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,4570,7-153-10364_52259_10951_11304---,00.html FISHERIES DIVISION LSCFRS History - 1 History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966-2003 Preface: the other “old” guys at the station. It is my From 1992 to 2016, it was my privilege to hope that this “report” will be updated serve as a fisheries research biologist at the periodically by Station crew members who Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station have an interest in making sure that the (LSCFRS). During my time at the station, I past isn’t forgotten. – Mike Thomas learned that there was a rich history of fisheries research and assessment work The Beginning - 1966-1971: that was largely undocumented by the By 1960, Great Lakes fish populations and standard reports or scientific journal the fisheries they supported had been publications. This history, often referred to decimated by degraded habitat, invasive as “institutional memory”, existed mainly in species, and commercial overfishing. The the memories of station employees, in invasive alewife was overabundant and vessel logs, in old 35mm slides and prints, massive die-offs ruined Michigan beaches.