Revolution, Freedom, and Oppression from Rivera to Coco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Cary Cordova Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO Committee: Steven D. Hoelscher, Co-Supervisor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Co-Supervisor Janet Davis David Montejano Deborah Paredez Shirley Thompson THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO by Cary Cordova, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2005 Dedication To my parents, Jennifer Feeley and Solomon Cordova, and to our beloved San Francisco family of “beatnik” and “avant-garde” friends, Nancy Eichler, Ed and Anna Everett, Ellen Kernigan, and José Ramón Lerma. Acknowledgements For as long as I can remember, my most meaningful encounters with history emerged from first-hand accounts – autobiographies, diaries, articles, oral histories, scratchy recordings, and scraps of paper. This dissertation is a product of my encounters with many people, who made history a constant presence in my life. I am grateful to an expansive community of people who have assisted me with this project. This dissertation would not have been possible without the many people who sat down with me for countless hours to record their oral histories: Cesar Ascarrunz, Francisco Camplis, Luis Cervantes, Susan Cervantes, Maruja Cid, Carlos Cordova, Daniel del Solar, Martha Estrella, Juan Fuentes, Rupert Garcia, Yolanda Garfias Woo, Amelia “Mia” Galaviz de Gonzalez, Juan Gonzales, José Ramón Lerma, Andres Lopez, Yolanda Lopez, Carlos Loarca, Alejandro Murguía, Michael Nolan, Patricia Rodriguez, Peter Rodriguez, Nina Serrano, and René Yañez. -

WHEREAS, LULAC Is Our Nation's Oldest, Largest, and Most Respected

RESOLUTION TO SUPPORT THE CHEECH MARIN CENTER FOR CHICANO ART, CULTURE, AND INDUSTRY WHEREAS, LULAC is our Nation’s oldest, largest, and most respected Hispanic/Latino civil rights organization, established in 1929. Our mission is to seek the advancement of Hispanic Americans in the areas of education, employment, and civil rights; and WHEREAS, for over 50 years, the Riverside Art Museum (RAM) has been the place in Inland Southern California where families and friends come to be engaged and inspired by visual art; and WHEREAS, RAM is a steward of the art and stories of the community via its Permanent Collection, and builds public value through its mission driven work; and WHEREAS, the Chicano Art Movement represents the establishment of a unique artistic identity by Mexican Americans in the United States and Chicanos who have used art to express their cultural values, both as protest and for aesthetic value; and WHEREAS, the art has evolved over time to not only illustrate current struggles and social issues, but also to continue to inform Chicano youth and unify around their culture and histories. Chicano art is not just Mexican-American artwork; it is a public forum that emphasizes otherwise “invisible” histories and people as a unique form of American art; and WHEREAS, Cheech Marin, an accomplished actor, director, writer, musician, art collector, and humanitarian is truly a multi-generational star, and Cheech Marin is the purveyor and collector of the largest Chicano art (over 700 pieces) in the United States; and WHEREAS, Cheech -

Oral History Interview with Barbara Carrasco

Oral history interview with Barbara Carrasco The digital preservation of this interview received Federal support from the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Barbara Carrasco AAA.carras99 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Barbara Carrasco Identifier: -

Oral History Interview with Ramses Noriega

Oral History interview with Ramses Noriega Noriega, Ramses, born 1944 Painter Los Angeles, California Part 1 of 2 Sound Cassette Duration – 24:12 INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT DENISE LUGO: […] Ramses, when were you born? RAMSES NORIEGA: I was born in Caborca, Sonora, Mexico in 1944. DENISE LUGO: When did you come to the United States? RAMSES NORIEGA: Well I came in 1956. So I spent […] 12 years approximately. DENISE LUGO: Your first language was Spanish then? RAMSES NORIEGA: My first language is Spanish. English is my second adoptive language. DENISE LUGO: When you came, where did you go? Where did you settle? RAMSES NORIEGA: I consider myself a sprit of movement and my first movement was from Caborca to Mexicali. From Mexicali I developed my world perspective of humanity and I developed my philosophy and it was there that began to do my artwork. My first art works that I could remember were in two forms. They were what we used to call monitos de barro (clay/mud dolls) and they were graphics, drawing with pencil and with sticks or we would scratch the ground a lot and draw. And with the pencils we also used to do a lot of drawing on books, on wood, on anything that would be on flat that would take a pencil. I recall images from those days. The types of images we used to do in those days there was “El Santo” which was a luchador (Mexican wrestler) and we liked that. And there was another one, “Superman”. Which is called “Superman” in English and we used these characters. -

Art, Culture Making, and Representation As Resistance in the Life of Manuel Gregorio Acosta Susannah Aquilina University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2016-01-01 Art, Culture Making, and Representation as Resistance in the Life of Manuel Gregorio Acosta Susannah Aquilina University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Aquilina, Susannah, "Art, Culture Making, and Representation as Resistance in the Life of Manuel Gregorio Acosta" (2016). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 801. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/801 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ART, CULTURE MAKING, AND REPRESENTATION AS RESISTANCE IN THE LIFE OF MANUEL GREGORIO ACOSTA SUSANNAH ESTELLE AQUILINA Doctoral Program in Borderlands History APPROVED: Ernesto Chávez, Ph.D., Chair Michael Topp, Ph.D. Yolanda Chávez Leyva, Ph.D. Melissa Warak, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Susannah Estelle Aquilina 2016 This dissertation is dedicated to Stone, Mila, Silver and all of you young ones who give us hope. ART, CULTURE MAKING, AND REPRESENTATION AS RESISTANCE IN THE LIFE OF MANUEL GREGORIO ACOSTA by SUSANNAH ESTELLE AQUILINA, B.A., M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2016 Acknowledgements I am indebted with gratitude to Dr. -

Chicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest

Chicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest Exhibit Catalog Reformatted for use on the Chicano/Latino Archive Web site at The Evergreen State College www.evergreen.edu/library/ chicanolatino 2 | Chicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest A touring exhibition and catalog, with interpretive historical and cultural materials, featuring recent work of nine contemporary artists and essays by five humanist scholars. This project was produced at The Evergreen State College with primary funding support from the Washington Commission for the Humanities and the Washington State Arts Commission Preliminary research for this arts and humanities project was carried out in 1982 with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Exhibiting Artists Cecilia Alvarez Alfredo Arreguín Arturo Artorez Paul Berger Eduardo Calderón José E. Orantes José Reynoso José Luís Rodríguez Rubén Trejo Contributing Authors Lauro Flores Erasmo Gamboa Pat Matheny-White Sid White Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Contents ©1984 | 3 Introduction and Acknowledgements TheChicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest During the first phase of this project, funded by the project is the first effort to develop a major touring National Endowment for the Humanities in 1982, primary exhibition presenting works by Pacific Northwest Chicano field research was completed to identify artists’ public and and Latino artists. This project also features a catalog and personal work, and to gather information on social, cultural other interpretive materials which describe the society and and demographic patterns in Washington, Oregon and culture of Chicano/Latino people who have lived in this Idaho. Materials developed in the NEH project included region for generations, and the popular and public art that a demographic study by Gamboa, an unpublished social has expressed the heritage, struggles and aspirations of this history of artists by Ybarra-Frausto, and a survey of public community. -

Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals a National Register Nomination

CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION Josie S. Talamantez B.A., University of California, Berkeley, 1975 PROJECT Submitted in partial satisfaction of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY (Public History) at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2011 CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION A Project by Josie S. Talamantez Approved by: _______________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Lee Simpson _______________________________, Second Reader Dr. Patrick Ettinger _______________________________ Date ii Student:____Josie S. Talamantez I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and this Project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the Project. ______________________, Department Chair ____________________ Aaron Cohen, Ph.D. Date Department of History iii Abstract of CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION by Josie S. Talamantez Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals Chicano Park is a 7.4-acre park located in San Diego City’s Barrio Logan beneath the east-west approach ramps of the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge where the bridge bisects Interstate 5. The park was created in 1970 after residents in Barrio Logan participated in a “takeover” of land that was being prepared for a substation of the California Highway Patrol. Barrio Logan the second largest barrio on the West Coast until national and state transportation and urban renewal public policies, of the 1950’s and 1960’s, relocated thousands of residents from their self-contained neighborhood to create Interstate 5, to rezone the area from residential to light industrial, and to build the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge. -

A Finding Aid to the Tomás Ybarra- Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, 1965-2004, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Tomás Ybarra- Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, 1965-2004, in the Archives of American Art Gabriela H. Lambert, Rosa Fernández and Lucile Smith 1998, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Autobiographical Note...................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Subject Files, 1965-2004.......................................................................... 5 Tomás Ybarra-Frausto research material AAA.ybartoma Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Tomás Ybarra-Frausto research material Identifier: AAA.ybartoma Date: 1965-2004 Creator: -

The Place of Chicana Feminism and Chicano Art in the History

THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM A Project Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Beatriz Anguiano FALL 2012 © 2012 Beatriz Anguiano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM A Project by Beatriz Anguiano Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Chloe S. Burke __________________________________, Second Reader Donald J. Azevada, Jr. ____________________________ Date \ iii Student: Beatriz Anguiano I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________, Chair ___________________ Mona Siegel, PhD Date Department of History iv Abstract of THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM by Beatriz Anguiano Statement of Problem Chicanos are essentially absent from the State of California United States History Content Standards, as a result Chicanos are excluded from the narrative of American history. Because Chicanos are not included in the content standards and due to the lack of readily available resources, this presents a challenge for teachers to teach about the role Chicanos have played in U.S. history. Chicanas have also largely been left out of the narrative of the Chicano Movement, also therefore resulting in an incomplete history of the Chicano Movement. This gap in our historical record depicts an inaccurate representation of our nation’s history. -

![SELF HELP GRAPHICS ARCHIVES 1960 – 2003 [Bulk 1972-1992]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5869/self-help-graphics-archives-1960-2003-bulk-1972-1992-2725869.webp)

SELF HELP GRAPHICS ARCHIVES 1960 – 2003 [Bulk 1972-1992]

University of California, Santa Barbara Davidson Library Department of Special Collections California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives GUIDE TO THE SELF HELP GRAPHICS ARCHIVES 1960 – 2003 [bulk 1972-1992] Collection Number: CEMA 3 Size Collection: 27 linear feet of organizational records and four hundred sixty six silk screen prints. Acquisition Information: Donated by Self Help Graphics & Art, Inc., 1986-2004 Access restrictions: None Use Restriction: Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. Processing Information: Project Archivist Salvador Güereña. Principal processors Rosemary León, Alicia E. Rodríquez, Naomi Ramieri-Hall, Alexander Hauschild, Victor Alexander Muñoz, Maria Velasco, and Benjamin Wood. Curatorial support Zuoyue Wang. Processed July 1993-2005. Callie Bowdish and Paola Nova processed series IX, Sister Karen Boccalero’s photos and artwork February 2009. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Office of the President, and University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Location: Del Norte ORGANIZATIONAL HISTORY Self-Help Graphics & Art, Inc. is a non-profit organization and serves as an important cultural arts center that has encouraged and promoted Chicano art in the Los Angeles community and beyond. The seeds of what would become Self-Help Graphics & Art, Inc. -

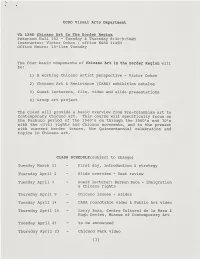

UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art

- UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art In The Border Region Peterson Hall 102 - Tuesday & Thursday 8:30-9:50AM Instructor: Victor Ochoa / office H&SS 1145D Office Hours: 10-11am Tuesday The four basic components of Chicano Art in the Border Region will be: 1) A working Chicano artist perspective - Victor Ochoa 2) Chicano Art & Resistance (CARA) exhibition catalog 3) Guest lecturers, film, video and slide presentations 4) Group art project The class will provide a basic overview from Pre-Colombian art to Contemporary Chicano art. This course will specifically focus on the Pachuco period of the 1940's on through the 1960's and 70's with the civil rights and Chicano movements, and to the present with current border issues, the Quincentennial celebration and topics in Chicana art. CLASS SCHEDULE(subject to change) Tuesday March 31 First day, introduction & strategy Thursday April 2 Slide overview - Text review Tuesday April 7 Guest lecturer: Herman Baca - immigration & Chicano rights Thursday April 9 - Chicano issues - slides Tuesday April 14 - CARA roundtable video & Public Art video Thursday April 16 - Larry Baza, Centro Cultural de la Raza & Hugh Davies, Museum of Contemporary Art Tuesday April 21 - to be announced Thursday April 23 - Chicano Park video [1] VA 128D(cont.) Saturday April 25 - Chicano Park Day - required field trip Tuesday April 28 - Issac Artenstein - "Mi Otro Yo" & video potpourri Thursday April 30 - Ireina Cervantes: personal work, Chicanas & Frida (Midterm due) Tuesday May 5 - David Avalos & BAW/TAF the -

Melina Mardueño Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite For

Traduciendo Mi Reflejo: Do You See Me? Melina Mardueño Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Studio Art under the advisement of Daniela Rivera and Andrew Mowbray April 2018 © 2018 Melina Mardueño Mardueño 1 Table of Contents I. Acknowledgments II. Reflections on the Origins of my Self-Portrait III. Loss and Distance IV. Coming to Terms with Chicanidad V. Visibility and the Invisible VI. Fulano, Mengano, Zutano, and Perengano VII. Identification VIII. There I am IX. That I Painted My Hair X. Hair and Gender XI. Clothing and Self-Fashioning XII. Closing Thoughts XIII. Bibliography Mardueño 2 Acknowledgements: First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisors Andy and Daniela for encouraging me to take on a senior thesis. Despite all of my self-doubt, they built me back up and reminded me that I was just as capable as anyone else. They remind me all the time why I am grateful to have them as professors and mentors. I would also like to thank the faculty and staff Art Department for all that they do and everyone on my thesis review committee for their time. Thank you to my fellow studio art seniors and friends; especially to Natalí for all of the favors she gave me and Anjali for our inspired conversations. Thank you to my siblings for always encouraging me and especially my brother Francisco for collecting so much of my material for me over the course of the year. To my mother and father, thank you for giving me the opportunity to become who I am.