Historical Overview of SC Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Carolina Statewide Comprehensive Multimodal Transportation Plan

SOUTH CAROLINA STATEWIDE COMPREHENSIVE MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT SUMMARY May 2008 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT SUMMARY Public involvement is a key component of the state’s transportation planning process. The proactive public involvement process is one that provides complete information, timely public notice, full public access to major transportation decisions, and supports early and continuing involvement of the public in developing transportation plans. Every citizen must have the opportunity to take part, feel entitled to participate, welcome to join in, and able to influence the transportation decisions made by SCDOT. The Public Involvement Process therefore adheres to SCDOT’s Public Participation Plan to provide the necessary framework in accomplishing identified goals. Included in the Multimodal Plan’s Public Involvement Process for both the rural and urban areas of the state were: o Stakeholder Meetings o Presentations o Surveys o Website o Interviews o Media o Focus Groups o Public Meetings Each component is summarized below, and detailed in the full Plan. Stakeholder Meetings A kick-off meeting was held for on July 6, 2006 at SCDOT to discuss the process and elements of the Plan. This meeting was attended by members of the Multimodal Plan Resource Committee, as well as other stakeholders. Specifically for development of the Regional Human Services Transportation Coordination Plans, at least three stakeholder meetings were held in each region. These meetings were attended by transit providers, MPOs, COGs, human service agencies, private entities, and public interest groups. Additional stakeholder meetings and conference calls were held for multiple elements of the Plan at various times throughout the Plan’s development, and attended by Resource Committee and Sub-Committee members, as well as other public and private stakeholders. -

Ederal Register

EDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 20 7S*. 1934 NUMBER 68 ' ^NlTtO •* Washington, Thursday, April 7 , 7955 TITLE 5— ADMINISTRATIVE 5. Effective as of the beginning of the CONTENTS first pay period following April 9, 1955, PERSONNEL paragraph (a) is amended by the addi Agricultural Marketing Service Pa&e tion of the following post: Chapter I— Civil Service Commission Rules and regulations: Artibonite Valley (including Bois Dehors), School lunch program, 1955__ 2185 H aiti. P art 6— E x c eptio n s P rom t h e Agriculture Department C o m petitiv e S ervice 6. Effective as of the beginning of the See Agricultural Marketing Serv C iv il. SERVICE COMMISSION first pay period following December 4, ice. 1954, paragraph (b) is amended by the Atomic Energy Commission Effective upon publication in the F ed addition of the following posts: Proposed rule making: eral R egister, paragraph (c) of § 6.145 Boudenib, Morocco. Procedure on applications for is revoked. Guercif, Morocco. determination of reasonable (R. S. 1753, sec. 2, 22 S tat. 403; 5 U. S. C. 631, Tiznit, Morocco. royalty fee, Just compensa 633; E. O. 10440, 18 P. R. 1823, 3 CFR, 1953 7. Effective as of the beginning of the tion, or grant of award for Supp.) first pay period following March 12,1955, patents, inventions or dis U n ited S tates C iv il S erv- paragraph (b) is amended by the addi coveries__________________ 2193 vice C o m m issio n , tion of the following posts: [seal] W m . C. H u l l , Civil Aeronautics Administra Executive Assistant. -

North Carolina Vs Clemson (11/3/1990)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1990 North Carolina vs Clemson (11/3/1990) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "North Carolina vs Clemson (11/3/1990)" (1990). Football Programs. 212. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/212 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Today's Features Clemson vs. North Carolina November 3, 1990 5 Jerome Henderson Although Clemson defensive back Jerome Henderson is not one of the largest players on the Tiger defense, there is no doubt in anyone's mind that when it comes to respect from his teammates, he is on top of the list, as Annabelle Vaughan explains. 7 Arlington Nunn On a squad that ranks number one in the country in total defense, there are many stars, but as Annabelle Vaughan explains. Academic AII-ACC selection Arlington Nunn has helped the Tigers with his consistent play on the field and his hard work off the field. -

Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) ) ) )

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC In the matter of: ) ) Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) MB Docket 13-249 ) ) COMMENTS OF REC NETWORKS One of the primary goals of REC Networks (“REC”)1 is to assure a citizen’s access to the airwaves. Over the years, we have supported various aspects of non-commercial micro- broadcast efforts including Low Power FM (LPFM), proposals for a Low Power AM radio service as well as other creative concepts to use spectrum for one way communications. REC feels that as many organizations as possible should be able to enjoy spreading their message to their local community. It is our desire to see a diverse selection of voices on the dial spanning race, culture, language, sexual orientation and gender identity. This includes a mix of faith-based and secular voices. While REC lacks the technical knowledge to form an opinion on various aspects of AM broadcast engineering such as the “ratchet rule”, daytime and nighttime coverage standards and antenna efficiency, we will comment on various issues which are in the realm of citizen’s access to the airwaves and in the interests of listeners to AM broadcast band stations. REC supports a limited offering of translators to certain AM stations REC feels that there is a segment of “stand-alone” AM broadcast owners. These owners normally fall under the category of minority, women or GLBT/T2. These owners are likely to own a single AM station or a small group of AM stations and are most likely to only own stations with inferior nighttime service, such as Class-D stations. -

2006 Report of Gifts (133 Pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons University South Caroliniana Society - Annual South Caroliniana Library Report of Gifts 4-29-2006 2006 Report of Gifts (133 pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scs_anpgm Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation University South Caroliniana Society. (2006). "2006 Report of Gifts." Columbia, SC: The ocS iety. This Newsletter is brought to you by the South Caroliniana Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University South Caroliniana Society - Annual Report of Gifts yb an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The The South Carolina South Caroliniana College Library Library 1840 1940 THE UNIVERSITY SOUTH CAROLINIANA SOCIETY SEVENTIETH ANNUAL MEETING UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA Saturday, April 29, 2006 Mr. Steve Griffith, President, Presiding Reception and Exhibit .............................. 11:00 a.m. South Caroliniana Library Luncheon .......................................... 1:00 p.m. Capstone Campus Room Business Meeting Welcome Reports of the Executive Council and Secretary-Treasurer Address .................................... Dr. A.V. Huff, Jr. 2006 Report of Gifts to the South Caroliniana Library by Members of the Society Announced at the 70th Meeting of the University South Caroliniana Society (the Friends of the Library) Annual Program 29 April 2006 A Life of Public Service: Interviews with John Carl West - 2005 Keynote Address by Gordon E. Harvey Gifts of Manuscript South Caroliniana Gifts of Printed South Caroliniana Gifts of Pictorial South Caroliniana South Caroliniana Library (Columbia, SC) A special collection documenting all periods of South Carolina history. -

ETV Annual Report 1977-1978.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT of the SOUTH CAROLINA EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION . COMMISSION For The Fiscal Year From July 1, 1977 to June 30, 1978 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. HISTORY ........................................... 5 II. UTILIZATION AND SERVICES PROVIDED .............. 14 A. Summary of ETV's Purposes and Services .......... 14 B. Public School Utilization .......................... 15 1. Instructional Television ........................ 15 2. Instructional Radio ............................ 15 3. lTV Course Enrollment Chart ................... 16 4. lTV Student Enrollment Chart .................. 17 C. Course Enrollment Summary ...................... 18 1. Instructional Television ........................ 18 2. Instructional Radio ............................ 18 D. Utilization of Individual Courses .................. 18 1. Instructional Television ........................ 18 2. Instructional Radio ............................ 22 E. Courses by Grade Level .......................... 23 1. Instructional Television ........................ 23 2. Instructional Radio ............................ 25 F. Staff Development Education for Teachers ......... 26 1. Certification Credit ........................... 27 2. Adult Education .............................. 27 3. Curriculum Areas ............................. 28 4. Custodial Training ............................ 29 5. Early Childhood Education .................... 29 6. Educational Products Center .................. 29 7. Guidance .................................... 29 8. Handicapped ................................ -

FY17 Cleanup Anderson Univ SC.Pdf

Anderson University – Former Pro Weave Property FY2017 US Environmental Protection Agency Cleanup Grant Application NARRATIVE PROPOSAL/RANKING CRITERIA 1. COMMUNITY NEED 1.a. Target Community and Brownfields 1.a.i. Community and Target Area Descriptions The City of Anderson is a small community with a population under 27,000 individuals (2014 ACS US Census) in the Upstate region of South Carolina along Interstate 85. The arrival to the region of the Pelzer Manufacturing Company and the railroad in the late 1880s resulted in significant economic growth and the development of many textile mills. Anderson was one of the first in the Southeastern United States to have electricity, which was provided by a hydroelectric plant on the Rocky River built in 1895. Anderson’s economy was historically based on the textile industry and a manufacturing sector connected to the region’s automotive industry cluster, including companies producing automotive products, metal parts, industrial machinery, plastics and textiles. Anderson is also the home of Anderson University, a private university of nearly 3,500 undergraduate and graduate students. Founded in 1911 as a four-year woman’s college, the University is now the second largest private college in South Carolina serving both men and women – offering a diverse curriculum of bachelor, masters and doctorate-level degree programs. The university has long history of giving back to the community. In keeping with this tradition, Anderson University has undertaken the revitalization of the wetlands property adjoining its campus in the targeted brownfields area. The Rocky River has a long history of abuse, including contamination from adjacent industries and the channelization of the river in the 1980’s, which separated it from the surrounding wetlands leading to degradation of these vital ecosystems. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

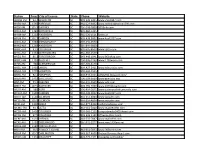

Complete Radio Roster

Station Freq City of License State Phone Website WAAW-FM 94.7 WILLISTON SC 803-649-6405 www.shout947.com WABV-AM 1590 ABBEVILLE SC 864-223-9402 www.radioinspiracion1590.com WOSF-FM 105.3 GAFFNEY SC 704-548-7800 1053rnb.com WAGS-AM 1380 BISHOPVILLE SC 803-484-5415 WAIM-AM 1230 ANDERSON SC 864-226-1511 waim.us WPUB-FM 102.7 CAMDEN SC 803-438-9002 www.kool1027.com WALD-AM 1080 JOHNSONVILLE SC 803-939-9530 WANS-AM 1280 ANDERSON SC 864-844-9009 WARQ-FM 93.5 COLUMBIA SC 803-695-8600 www.q935.com WASC-AM 1530 SPARTANBURG SC 864-585-1530 WKZQ-FM 96.1 FORESTBROOK SC 843-448-1041 www.961wkzq.com WAVO-AM 1150 ROCK HILL SC 704-596-1240 www.1150wavo.com WAZS-AM 980 SUMMERVILLE SC 704-405-3170 WBCU-AM 1460 UNION SC 864-427-2411 www.wbcuradio.com WHGS-AM 1270 HAMPTON SC 803-943-5555 WBHC-FM 92.1 HAMPTON SC 803-943-5555 allhits921.blogspot.com/ WBLR-AM 1430 BATESBURG SC 706-309-9609 www.gnnradio.org WBT-FM 99.3 CHESTER SC 704-374-3500 www.wbt.com WNKT-FM 107.5 EASTOVER SC 803-796-7600 www.1075thegame.com WULR-AM 980 YORK SC 336-434-5025 www.cadenaradialnuevavida.com WCAM-AM 1590 CAMDEN SC 803-438-9002 www.kool1027.com WAHT-AM 1560 CLEMSON SC 864-654-4004 www.wccpfm.com WCCP-FM 105.5 CLEMSON SC 864-654-4004 www.wccpfm.com WCKI-AM 1300 GREER SC 864-877-8458 catholicradioinsc.com WCMG-FM 94.3 LATTA SC 843-661-5000 www.magic943fm.com WCOS-AM 1400 COLUMBIA SC 803-343-1100 foxsportsradio1400.iheart.com WCOS-FM 97.5 COLUMBIA SC 803-343-1100 975wcos.iheart.com WCRE-AM 1420 CHERAW SC 843-537-7887 www.myfm939.com WCRS-AM 1450 GREENWOOD SC 864-941-9277 www.wcrs1450am.net -

Freq Call State Location U D N C Distance Bearing

AM BAND RADIO STATIONS COMPILED FROM FCC CDBS DATABASE AS OF FEB 6, 2012 POWER FREQ CALL STATE LOCATION UDNCDISTANCE BEARING NOTES 540 WASG AL DAPHNE 2500 18 1107 103 540 KRXA CA CARMEL VALLEY 10000 500 848 278 540 KVIP CA REDDING 2500 14 923 295 540 WFLF FL PINE HILLS 50000 46000 1523 102 540 WDAK GA COLUMBUS 4000 37 1241 94 540 KWMT IA FORT DODGE 5000 170 790 51 540 KMLB LA MONROE 5000 1000 838 101 540 WGOP MD POCOMOKE CITY 500 243 1694 75 540 WXYG MN SAUK RAPIDS 250 250 922 39 540 WETC NC WENDELL-ZEBULON 4000 500 1554 81 540 KNMX NM LAS VEGAS 5000 19 67 109 540 WLIE NY ISLIP 2500 219 1812 69 540 WWCS PA CANONSBURG 5000 500 1446 70 540 WYNN SC FLORENCE 250 165 1497 86 540 WKFN TN CLARKSVILLE 4000 54 1056 81 540 KDFT TX FERRIS 1000 248 602 110 540 KYAH UT DELTA 1000 13 415 306 540 WGTH VA RICHLANDS 1000 97 1360 79 540 WAUK WI JACKSON 400 400 1090 56 550 KTZN AK ANCHORAGE 3099 5000 2565 326 550 KFYI AZ PHOENIX 5000 1000 366 243 550 KUZZ CA BAKERSFIELD 5000 5000 709 270 550 KLLV CO BREEN 1799 132 312 550 KRAI CO CRAIG 5000 500 327 348 550 WAYR FL ORANGE PARK 5000 64 1471 98 550 WDUN GA GAINESVILLE 10000 2500 1273 88 550 KMVI HI WAILUKU 5000 3181 265 550 KFRM KS SALINA 5000 109 531 60 550 KTRS MO ST. LOUIS 5000 5000 907 73 550 KBOW MT BUTTE 5000 1000 767 336 550 WIOZ NC PINEHURST 1000 259 1504 84 550 WAME NC STATESVILLE 500 52 1420 82 550 KFYR ND BISMARCK 5000 5000 812 19 550 WGR NY BUFFALO 5000 5000 1533 63 550 WKRC OH CINCINNATI 5000 1000 1214 73 550 KOAC OR CORVALLIS 5000 5000 1071 309 550 WPAB PR PONCE 5000 5000 2712 106 550 WBZS RI -

Sryl: . Broar .T:R Ydor Ua:Al NG "%1J $T4 Cyrt,Io Suo=.Tsir¿

SEPTEMBER 26, 1955 35c PER COPY gg8 Ie d sryL:_. BROAr .t:r yDOr ua:aL NG "%1j $t4 cyrT,Io suo=.Tsir¿. .T,, !3-T6.In ` F IL,IQ,1 Tun .rTf..aycn T E 1.e44 vihifria..... Complete Index Page 10 W110 IS IOWA'S FAVORITE RADIO STATION Wants " ore V's, Forget the U's FOR Page 27 FARM PROGRAMS! Advice on Spot Radio BBDO's Anderson Page 30 n l n- -1 I . v Has Saturated WHO WMT Wgl'i NAX WOW KMA KICD KGLO KSCJ KXEL 0% of City Homes `,. 44.6% 18.8 %A ° 4.3 % x,4.1 3.9 1.5% 1.3 1.3% 1.1% Page 32 o rnu 4o More Film Firms' Drop Tv Boycott THE data i_n 4 tre otre crt Oi Dr. Forest L. Whañ s owa Radi. evision Audience Survey -the of this famed study. Farming is big business in Iowa, and Iowans' overwhelming preference for WHO farm program is FEATURE SECTiON far from a freak. It's the result of heads -up planning Begins on Page 37 -in programming, personnel and research . in Public Service and audience promotion. BUY ALL of IOWA - Write direct or ask Free & Peters for your copy of the 1954 I.R.T.A. Survey. It will tell you more about Plus `Iowa Plus" -with radio and television in Iowa than you could glean from weeks of personal travel and study. WHO Des Moines . 50,000 Waits & PETERS, INC., Col. )}. J. Palmer, President National Representatives THE NEWSWEEKLY P. A. Loyet, Resident Manager OF RADIO AND TV "The South's First Television Station" ELE ISION ICHMOND RICHMOND, VA. -

Broadcast Actions 11/30/2011

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 47623 Broadcast Actions 11/30/2011 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 11/25/2011 LOW POWER FM APPLICATIONS FOR MINOR CHANGE TO A LICENSED FACILITY DISMISSED CO BPL-20111117ALL KGJN-LP COLORADO, STATE OF, Low Power FM minor change in licensed facilities. 131667 TELECOM SERVS E 96.5 MHZ CO , GRAND JUNCTION AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MINOR CHANGE TO A LICENSED FACILITY GRANTED CA BP-20110809ABE KIGS 51122 PEREIRA BROADCASTING Minor change in licensed facilities. E 620 KHZ CA , HANFORD AZ BP-20110809ABT KBLU 62233 EDB YUMA LICENSE LLC Minor change in licensed facilities. E 560 KHZ AZ , YUMA OR BP-20110822ABX KBNH 62265 HARNEY COUNTY RADIO, LLC Minor change in licensed facilities. E 1230 KHZ OR , BURNS AR BP-20110822AEO KWAK 2774 ARKANSAS COUNTY Minor change in licensed facilities. BROADCASTERS, INC. E 1240 KHZ AR , STUTTGART Page 1 of 168 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 47623 Broadcast Actions 11/30/2011 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 11/25/2011 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MINOR CHANGE TO A LICENSED FACILITY GRANTED SC BP-20110829ABM WJMX 3112 QANTUM OF FLORENCE Minor change in licensed facilities.