Hemorrhagic Vasculitis (Schönlein-Henoch Disease)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Science of ITP

CHAPTER 1 Basic sc*ience of ITP Editor: John W. Semple 1.1 Megakaryocyte differentiation and platelet produc*tion A.S. Weyrich 1.2 Autoimmune mechanisms and T regula*tory cell disturbances in ITP K. Yazdanbakhsh 1.3 Mouse models o*f ITP J.W. Semple 1.4 Peptide therapy for patients with* ITP S.J. Urbaniak * Basic science of ITP 1.1 Megakaryocyte differen*tiation and platelet production Andrew S. Weyrich CHAPTER 1.1 • Megakaryocyte differentiation and platelet production 1. Introduction Platelets are anucleate cells that circulate in the bloodstream for approximately 10 days. The average adult must produce roughly 1 x 10 11 platelets per day to maintain normal platelet counts, a level of production that increases dramatically in a variety of clinical scenarios (1). In 1906, Wright provided the first evidence that megakaryocytes give rise to blood platelets. Since then, our understanding of the molecular basis of thrombopoiesis has progressed substantially and is arguably in a logarithmic growth phase. This chapter will review our current understanding of thrombopoiesis and highlight how the field is evolving. The history of megakaryocytes and platelets is fairly young. In 1841, Addison first described platelets and in 1882, Bizzozero named and identified platelets in the circulation and determined that they could induce clotting. In 1890, Howell named megakaryocytes, and 16 years later, Wright discovered that these were actually the precursors of platelets. Thus, the late 1880’s and early 1900’s were a period of prolific activity in the elucidation of megakaryocytes. Several discoveries were made about platelets and also about erythropoietin, which implied that a humoral substance also regulated platelet production though its exact nature was not yet known. -

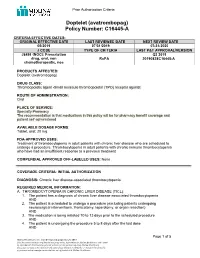

Doptelet (Avatrombopag) Policy Number: C16445-A

Prior Authorization Criteria Doptelet (avatrombopag) Policy Number: C16445-A CRITERIA EFFECTIVE DATES: ORIGINAL EFFECTIVE DATE LAST REVIEWED DATE NEXT REVIEW DATE 05/2019 07/31/2019 07/31/2020 J CODE TYPE OF CRITERIA LAST P&T APPROVAL/VERSION J8499 (NOC): Prescription Q3 2019 drug, oral, non RxPA 20190828C16445-A chemotherapeutic, nos PRODUCTS AFFECTED: Doptelet (avatrombopag) DRUG CLASS: Thrombopoietic agent -Small molecule thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonist ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION: Oral PLACE OF SERVICE: Specialty Pharmacy The recommendation is that medications in this policy will be for pharmacy benefit coverage and patient self-administered AVAILABLE DOSAGE FORMS: Tablet, oral: 20 mg FDA-APPROVED USES: Treatment of thrombocytopenia in adult patients with chronic liver disease who are scheduled to undergo a procedure. Thrombocytopenia in adult patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an insufficient response to a previous treatment COMPENDIAL APPROVED OFF-LABELED USES: None COVERAGE CRITERIA: INITIAL AUTHORIZATION DIAGNOSIS: Chronic liver disease-associated thrombocytopenia REQUIRED MEDICAL INFORMATION: A. THROMBOCYTOPENIA IN CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE (TICL): 1. The patient has a diagnosis of chronic liver disease-associated thrombocytopenia AND 2. The patient is scheduled to undergo a procedure (excluding patients undergoing neurosurgical interventions, thoracotomy, laparotomy, or organ resection) AND 3. The medication is being initiated 10 to 13 days prior to the scheduled procedure AND 4. The patient is undergoing the procedure 5 to 8 days after the last dose AND Page 1 of 5 Molina Healthcare, Inc. confidential and proprietary © 2018 This document contains confidential and proprietary information of Molina Healthcare and cannot be reproduced, distributed or printed without written permission from Molina Healthcare. -

Long Term in Vivo Study of Rapidly Degradable Synthetic Arterial Grafts R

Society for Biomaterials Annual Meeting and Exposition 2013 Biomaterials Revolution Transactions of the 37th Annual Meeting Volume XXXV Boston, Massachusetts, USA 10-13 April 2013 Volume 1 of 2 ISBN: 978-1-62748-128-1 ISSN: 1526-7547 Copyright and Disclaimer Society For Biomaterials Transactions of the 37th Annual Meeting Volume XXXV Published by: Society For Biomaterials 15000 Commerce Parkway, Suite C Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 (856)439-0826 Copyright © 2013 Society For Biomaterials, USA ISSN# 1526-7547 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by Photostat, microfilm, retrieval system, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. The materials published in this volume are not intended to be considered by the reader as statements of standards of care or definitions of the state of the art in patient care or applications of the scientific principles described in the contents. The statements of fact and opinions expressed are those of the respective authors who are identified in the abstracts. Publications of these materials by the Society For Biomaterials does not express or imply approval or agreement of the officers, staff, or agents of the Society with the items presented herein and should not be viewed by the reader as an endorsement thereof. Neither the Society For Biomaterials nor its agents are responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in this Publication. Every effort has been made to faithfully reproduce these Transactions as submitted. No responsibility is assumed by the Organizers for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of product liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein. -

Simposio 9 Terapia Celular

Simposio 9 Terapia celular Moderadora: Pilar Ortiz. Banc de Sang i Teixits, Barcelona S9-1 Desarrollo de la hemopoyesis en humanos: del embrión al adulto A. Bigas. S9-2 Cellular immunotherapy against infectious agents P. Comoli. S9-3 Optimización de sistemas de producción celular con calidad GMP JJ. Cairó, J. Garcia. Simposio S9-1 Desarrollo de la hemopoyesis en humanos: del embrión al adulto Desarrollo de la hemopoyesis en humanos: del S9-1 embrión al adulto A. Bigas. Grupo de investigación en Células Madre y Cáncer. Programa de investigación en Cancer. IMIM-Hospital del Mar. Parc de Recerca Biomédica de Barcelona (PRBB). Introducción Las células madre hematopoyéticas son las responsables de la formación de células sanguíneas especializadas durante toda la vida. Para ello, estas células deben tener la capaci- dad de auto-renovación, así como de diferenciación hacia los distintos tipos celulares. La capacidad de autorenova- ción indefinida es la que diferencia a estas células de los progenitores multipotentes. Históricamente se han desarro- llado diversas técnicas para caracterizar y distinguir las células madre de otros precursores hematológicos indife- renciados. Actualmente, se considera que una célula madre hematopoyética es aquella que es capaz de reconstitutir la hematopoyesis al ser transplantada a un organismo inmu- nodeprimido1. Estas células residen en la médula ósea de una persona adulta y se perpetúan mediante auto-replica- ción. Sin embargo, en algún momento debe existir un pre- cursor a partir del cual las células madre del -

COMPARISON of the WHO ATC CLASSIFICATION & Ephmra/Intellus Worldwide ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION

COMPARISON OF THE WHO ATC CLASSIFICATION & EphMRA/Intellus Worldwide ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION November 2020 Comparison of the WHO ATC Classification and EphMRA / Intellus Worldwide Anatomical Classification The following booklet is designed to improve the understanding of the two classification systems. The development of the two systems had previously taken place separately. EphMRA and WHO are now working together to ensure that there is a convergence of the 2 systems rather than a divergence. In order to better understand the two classification systems, we should pay attention to the way in which substances/products are classified. WHO mainly classifies substances according to the therapeutic or pharmaceutical aspects and in one class only (particular formulations or strengths can be given separate codes, e.g. clonidine in C02A as antihypertensive agent, N02C as anti-migraine product and S01E as ophthalmic product). EphMRA classifies products, mainly according to their indications and use. Therefore, it is possible to find the same compound in several classes, depending on the product, e.g., NAPROXEN tablets can be classified in M1A (antirheumatic), N2B (analgesic) and G2C if indicated for gynaecological conditions only. The purposes of classification are also different: The main purpose of the WHO classification is for international drug utilisation research and for adverse drug reaction monitoring. This classification is recommended by the WHO for use in international drug utilisation research. The EphMRA/Intellus Worldwide classification has a primary objective to satisfy the marketing needs of the pharmaceutical companies. Therefore, a direct comparison is sometimes difficult due to the different nature and purpose of the two systems. The aim of harmonisation is to reach a “full” agreement of all mono substances in a given class as listed in the WHO ATC Index, mainly at third level: whenever this is not possible, or harmonisation of third level is too difficult or makes no sense (e.g. -

COVID-19 Vaccine Astrazeneca (Other Viral Vaccines) EPITT No:19683

24 March 2021 EMA/PRAC/157045/2021 Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) Signal assessment report on embolic and thrombotic events (SMQ) with COVID-19 Vaccine (ChAdOx1-S [recombinant]) – COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca (Other viral vaccines) EPITT no:19683 Confirmation assessment report 12 March 2021 Preliminary assessment report on additional data 17 March 2021 Adoption of first PRAC recommendation 18 March 2021 1 Administrative information Active substance (invented name)Error! AZD1222 (COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca) Bookmark not defined. Marketing authorisation holder AstraZeneca Authorisation procedure Centralised Mutual recognition or decentralised National Adverse event/reaction: embolic and thrombotic events Signal validated by: BE Date of circulation of signal validation 11 March 2021 report: Signal confirmed by: Belgium Date of confirmation: 12 March 2021 PRAC Rapporteur appointed for the Jean-Michel Dogné (BE) assessment of the signal: Signal assessment report on embolic and thrombotic events (SMQ) with COVID-19 Vaccine (ChAdOx1-S [recombinant]) – COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca (Other viral vaccines) EMA/PRAC/157045/2021 Page 2/50 Table of contents Administrative information ........................................................................................... 2 1. Background ............................................................................................. 4 2. Initial evidence ........................................................................................ 4 2.1. Signal validation .................................................................................................. -

Doptelet (Avatrombopag) C16445-A

Drug and Biologic Coverage Criteria Effective Date: 05/2019 Last P&T Approval/Version: 07/28/2021 Next Review Due By: 07/2022 Policy Number: C16445-A Doptelet (avatrombopag) PRODUCTS AFFECTED Doptelet (avatrombopag) COVERAGE POLICY Coverage for services, procedures, medical devices and drugs are dependent upon benefit eligibility as outlined in the member's specific benefit plan. This Coverage Guideline must be read in its entirety to determine coverage eligibility, if any. This Coverage Guideline provides information related to coverage determinations only and does not imply that a service or treatment is clinically appropriate or inappropriate. The provider and the member are responsible for all decisions regarding the appropriateness of care. Providers should provide Molina Healthcare complete medical rationale when requesting any exceptions to these guidelines Documentation Requirements: Molina Healthcare reserves the right to require that additional documentation be made available as part of its coverage determination; quality improvement; and fraud; waste and abuse prevention processes. Documentation required may include, but is not limited to, patient records, test results and credentials of the provider ordering or performing a drug or service. Molina Healthcare may deny reimbursement or take additional appropriate action if the documentation provided does not support the initial determination that the drugs or services were medically necessary, not investigational, or experimental, and otherwise within the scope of benefits afforded to the member, and/or the documentation demonstrates a pattern of billing or other practice that is inappropriate or excessive DIAGNOSIS: Chronic liver disease-associated thrombocytopenia REQUIRED MEDICAL INFORMATION: FOR ALL INDICATIONS: 1. Prescriber attests that Doptelet (acatrombopag) is not prescribed for, or intended for, the following: Concurrent use with, another thrombopoietic agent or spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor [e.g., Promacta (eltrombopag), Nplate (romiplostim), or Tavalisse (fotamatinib)] AND 2. -

Perioperative Medication Management - Adult/Pediatric - Inpatient/Ambulatory Clinical Practice Guideline

Effective 6/11/2020. Contact [email protected] for previous versions. Perioperative Medication Management - Adult/Pediatric - Inpatient/Ambulatory Clinical Practice Guideline Note: Active Table of Contents – Click to follow link INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 3 SCOPE....................................................................................................................................... 3 DEFINITIONS .............................................................................................................................. 3 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................... 4 METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................................................28 COLLATERAL TOOLS & RESOURCES..................................................................................................31 APPENDIX A: PERIOPERATIVE MEDICATION MANAGEMENT .................................................................32 APPENDIX B: TREATMENT ALGORITHM FOR THE TIMING OF ELECTIVE NONCARDIAC SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH CORONARY STENTS .....................................................................................................................58 APPENDIX C: METHYLENE BLUE AND SEROTONIN SYNDROME ...............................................................59 APPENDIX D: AMINOLEVULINIC ACID AND PHOTOTOXICITY -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/01661 12 A1 Zhang (43) Pub

US 2011 01661 12A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/01661 12 A1 Zhang (43) Pub. Date: Jul. 7, 2011 (54) METHOD FOR STIMULATING PLATELET Publication Classification PRODUCTION (51) Int. Cl. A 6LX 3/573 (2006.01) (75) Inventor: Yanzhen Zhang, Sudbury, MA A63/496 (2006.01) (US) A6IP 7/02 (2006.01) A6IP35/00 (2006.01) (73) Assignee: Eisai, Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ A6IPL/I6 (2006.01) (US) A6IP3L/2 (2006.01) A6IP3L/04 (2006.01) (21) Appl. No.: 12/856,003 (52) U.S. Cl. ...................................... 514/171; 514/253.1 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Aug. 13, 2010 Provided are methods for increasing platelet response in a O O subject at risk for bleeding due at least in part to a low platelet Related U.S. Application Data count by administering to a subject with a low platelet count (60) Provisional application No. 61/234,153, filed on Aug. an effective amount of 1-(3-chloro-5-4-(4-chlorothiophen 14, 2009, provisional application No. 61/365,479, 2-yl)-5-(4-cyclohexylpiperazin-1-yl)thiazol-2-yl) filed on Jul.19, 2010. carbamoylpyridine-2-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid. Patent Application Publication Jul. 7, 2011 Sheet 1 of 5 US 2011/O1661 12 A1 -H PLACEBO 500 ---0--- E55O15 mg *-i- E550120 mg 450 ----- ------. E5501 2.5 mg -...-a-...-. E5501 10 mg 4OO 350 3OO Patent Application Publication Jul. 7, 2011 Sheet 4 of 5 US 2011/O1661 12 A1 WEEK 1 WEEK 2 WEEK 3 WEEK 4 TIME FROM DATE OF LAST DOSE Figure 4 Patent Application Publication Jul. -

Mulpleta (Lusutrombopag)

Drug and Biologic Coverage Criteria Effective Date: 05/01/2019 Last P&T Approval/Version: 07/28/2021 Next Review Due By: 08/2022 Policy Number: C16446-A Mulpleta (lusutrombopag) PRODUCTS AFFECTED Mulpleta (lusutrombopag) COVERAGE POLICY Coverage for services, procedures, medical devices and drugs are dependent upon benefit eligibility as outlined in the member's specific benefit plan. This Coverage Guideline must be read in its entirety to determine coverage eligibility, if any. This Coverage Guideline provides information related to coverage determinations only and does not imply that a service or treatment is clinically appropriate or inappropriate. The provider and the member are responsible for all decisions regarding the appropriateness of care. Providers should provide Molina Healthcare complete medical rationale when requesting any exceptions to these guidelines Documentation Requirements: Molina Healthcare reserves the right to require that additional documentation be made available as part of its coverage determination; quality improvement; and fraud; waste and abuse prevention processes. Documentation required may include, but is not limited to, patient records, test results and credentials of the provider ordering or performing a drug or service. Molina Healthcare may deny reimbursement or take additional appropriate action if the documentation provided does not support the initial determination that the drugs or services were medically necessary, not investigational or experimental, and otherwise within the scope of benefits afforded to the member, and/or the documentation demonstrates a pattern of billing or other practice that is inappropriate or excessive DIAGNOSIS: Chronic liver disease-associated thrombocytopenia REQUIRED MEDICAL INFORMATION: A. THROMBOCYTOPENIA (WITH CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE): 1. The member has a diagnosis of chronic liver disease-associated thrombocytopenia AND 2. -

Copyrighted Material

BLUKO82-Seeber March 13, 2007 17:50 Index Page numbers in bold represent tables; those in italics represent figures. 10/30 rule, 4 ε-aminocaproic acid (EACA), 81 1-deamino-8-D-argine vasopressin (DDAVP). -aminomethylbenzoic acid (PAMBA), 81 see desmopressin anabolic steroids androgen therapy, 30 A-ANA. see augmented acute normovolemic defined, 21 hemodilution anaphylactic transfusion reactions, 252 acetylstarch, 70 androgen therapy, 30 acute hypervolemic hemodilution (AHH) anemia advantages/disadvantages, 204 acute vs. chronic, 14 defined, 200 adaptive mechanisms technique, 203–04 cardiac output, 14 acute normovolemic hemodilution (ANH) macrocirculation, 14–15 advanced use, 207 microcirculation, 15–17 advantages/disadvantages, 206–07 oxygen extraction, 15 allogenic transfusion exposure, 207 oxygen uptake, 15, 16 and coronary artery stenosis, 204 tissue oxygenation, 16 defined, 200 vascular tone, 14 fractionation, 207 causes history, 200–201 copper deficiency, 40 indications/eligibility, 204 hematinic deficiencies, 45–47 technique of, 204–05 inactivity, 162–63 troubleshooting, 205–06 iron deficiency, 38–40 adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation, 13, 17 nutritional deficiencies, 46 AHH. see acute hypervolemic hemodilution pressure sores, 163 (AHH) riboflavin deficiency, 44 albumin clinical care pathway, 145 allergic reactions, 72 defined, 9 in AOCs, 115–16 pathophysiology of, 13–17 in coagulation impairment, 71 physiology of, 9–13 human, 271–72 preoperative treatment, 151 in recombinant blood products, 96–98, 103–04 primary prevention, 45–46 in volume -

China Regulatory and Market Access Pharmaceutical Report 2014

CHINA REGULATORY AND MARKET ACCESS PHARMACEUTICAL REPORT 2014 Pacific Bridge Medical 7315 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 609E Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: (301) 469-3400 Fax: (301) 469-3409 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2014 Pacific Bridge Medical. All rights reserved. This content is protected by US and International copyright laws and may not be copied, reprinted, published, translated, resold, hosted, or otherwise distributed by any means without explicit permission. Disclaimer: the information contained in this report is the opinion of Pacific Bridge Medical, a subsidiary of Pacific Bridge, Inc. It is provided for general information purposes only, and does not constitute professional advice. We believe the contents to be true and accurate at the date of writing but can give no assurances or warranties regarding the accuracy, currency, or applicability of any of the contents in relation to specific situations and particular circumstances. CHINA REGULATORY AND MARKET ACCESS PHARMACEUTICAL REPORT (2013) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. China Pharmaceutical Industry Overview .......................................................5 A. Overview B. China Pharmaceutical Market Trends C. China’s Pharmaceutical Distribution System D. Brief Overview of China’s Pharmaceutical Regulations E. China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) II. The China Healthcare System .........................................................................13 A. History of China’s Healthcare System B. Struggling Healthcare Services Sector C. 2009 Healthcare Reform D. Hospitals and Medical Resources 1. Hospitals in China 2. Current Problems in the Hospital Sector 3. Private Investment in the Hospital Sector 4. Hospital Reform E. Health Insurance in China III. Drug Registration Regulations ........................................................................21 A. Drug Registration Policy B. Classification of Drugs C. Drug Registration Applications D. Application Documents for New Drug Registration E.