Conceptual Art, Race, and Racial Issues in the Art Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth Anderson's Vita File:///C:/Users/Liz/Documents/Pub/Liz%20Webpages/Vita.Htm

Elizabeth Anderson's Vita file:///C:/Users/Liz/Documents/Pub/Liz%20Webpages/vita.htm ELIZABETH S. ANDERSON John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies Arthur F. Thurnau Professor University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Department of Philosophy Angell Hall 2239 / 435 South State St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1003 Office: 734-763-2118 Fax: 734-763-8071 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~eandersn/ EMPLOYMENT University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 2013-. John Rawls Collegiate Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 2005-. Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, 2004-. Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 1999-2005. Associate Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 1993-1999. Adjunct Professor of Law, 1995, 1999, 2000. Assistant Professor of Philosophy, 1987-1993. Swarthmore College, Visiting Instructor in Philosophy, 1985-6. Harvard University, Teaching Fellow, 1983-1985. EDUCATION Harvard University, Department of Philosophy, 1981-1987. A.M. Philosophy, 1984. Ph.D. 1987. Swarthmore College, 1977-1981. B.A. Philosophy with minor in Economics, High Honors, 1981. HONORS, GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS Nominee, Prospect’s World Thinkers 2014 Vice-President/President-Elect, Central Division, American Philosophical Association, 2013-15 Named John Dewey Distinguished University Professor, 2013 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, 2013 ACLS Fellowship, 2013 Michigan Humanities Award, 2013 (declined) Three -

Adrian Piper: a Catalyst for Social Change

1 Dwayne Hallager Professor Leah Peterson D-COM: Digital Media 19 April 2012 Adrian Piper: A Catalyst for Social Change Adrian Piper is more than meets the eye – literally. Piper can best be described as a conceptual artist with an ever-changing identity that reflects the struggles of black Americans and women in society. As a first-generation conceptual artist, her vast educational record attending and teaching at Harvard University, along with several other high scholastic institutions, allowed her to address issues of race, gender, and inequality as she transformed her body and physical presence to share her ideas. By incorporating her own identity in her work, and through the extensive practice of education and philosophy, Adrian Piper has exercised several mediums to produce art that has acted as a catalyst for social change. Similar to most artists, Adrian Piper has a compelling story for when she first recognized her inspiration to become an artist. In an interview with George Yancy, Piper describes her early childhood experiences growing up in a confusing and conflicting middle class neighborhood where her family was one of few black families in the area. It was here that Piper, a product of a German, Madagascan, and Nigerian lineage, first became aware of the situation that allowed her and several of her relatives to pass for white (Yancy 52). Piper claims that her parents and grandmother were responsible for her burning desire and passion to practice art and philosophy. The journey began first with her grandmother teaching her to draw and paint before age three; then following, the influence of her father’s being a lawyer and strong advocate for education, in addition to her mother’s analytical reasoning and logical 2 thinking, propelled Piper in her direction toward philosophy and an interest in artful expression (Yancy 55). -

Women of Color As Artists

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1996 Volume III: Race and Representation in American Cinema Women of Color as Artists Curriculum Unit 96.03.09 by Val-Jean Belton The New Haven public school system is a melting pot of many different cultures. The Fair Haven Middle school where I am one of two art teachers, is culturally very diverse. The student body is 65% Hispanic, 25% African American, and 10% White or other. I have observed that these students have little appreciation for visual arts. By offering lessons that center on various themes that are associated with their cultural heritage, I am able to gain and retain their attention. My lessons are taught in this particular manner in the hope that my students might better understand each others’ cultural heritage through hands-on experience in art. Despite my efforts to develop and teach art lessons that are not only culturally enriching but offer hands-on experience, I have had a tendency not to include information about the vast number of women artists. I have especially failed to include African American and Hispanic women artists who have contributed to our cultural experience. Although women artists have made major contributions to the art world, the extent of their accomplishments have been overshadowed by male artists such as Pablo Picasso, Jacob Lawrence, and Henri Matisse. There is little information available concerning women artists of African American and Hispanic descents available in our art curriculum, so they have not been included in the visual art classes that I teach. -

Curriculum Vitae Table of Contents

CURRICULUM VITAE Revised February 2015 ADRIAN MARGARET SMITH PIPER Born 20 September 1948, New York City TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Educational Record ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Languages...................................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Philosophy Dissertation Topic.................................................................................................................. 2 4. Areas of Special Competence in Philosophy ......................................................................................... 2 5. Other Areas of Research Interest in Philosophy ................................................................................... 2 6. Teaching Experience.................................................................................................................................... 2 7. Fellowships and Awards in Philosophy ................................................................................................. 4 8. Professional Philosophical Associations................................................................................................. 4 9. Service to the Profession of Philosophy .................................................................................................. 5 10. Invited Papers and Conferences in Philosophy ................................................................................. -

Adrian Piper: Concepts and Intuitions, 1965–2016 on View October 7, 2018 – January 6, 2019

Release: September 11, 2018 Contact: Nancy Lee, 310-443-7016, [email protected] Adrian Piper: Concepts and Intuitions, 1965–2016 On View October 7, 2018 – January 6, 2019 Organized by The Museum of Modern Art (Los Angeles, CA)— The Hammer Museum presents Adrian Piper: Concepts and Intuitions, 1965– 2016, the most comprehensive West Coast exhibition to date of the work of Adrian Piper (b. 1948, New York). Organized by The Museum of Modern Art, this expansive retrospective features more than 270 works gathered from public and private collections from around the world, and encompasses a wide range of mediums that Piper has explored for over 50 years: drawing, photography, works on paper, video, multimedia installations, performance, painting, sculpture, and sound. On view from October 7, 2018 through January 6, 2019, Adrian Piper: Concepts and Intuitions, 1965–2016 is the first West Coast museum presentation of Piper’s works in more than a decade, and her first since receiving the Golden Lion Award for Best Artist at the 56th Venice Biennale of 2015 and Germany’s Käthe Kollwitz Prize in 2018. Piper’s groundbreaking, transformative work has profoundly shaped the form and content of Conceptual art since the 1960s, exerting an incalculable influence on artists working today. Her investigations into the political, social, and spiritual potential of Conceptual art frequently address gender, race, and xenophobia through incisive humor and wit, and draw on her long-standing involvement with philosophy and yoga. “Adrian Piper’s fifty-year career -

Adrian Piper, Then and Again

Adrian Piper, Then and Again Isaiah Matthew Wooden hile ambling through the special exhibition gallery space on the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) sixth floor where nearly three Whundred works by the visual artist, philosopher, and self-avowed yoga enthusiast Adrian Piper were on view in Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016 (March 31–July 22, 2018), I found myself surprisingly overcome by an intense bout of emotions. Minutes after they had first piqued my curiosity, I decided to make my way over to a trio of what, from a distance, looked like family photos—one in black-and-white, and two in color—to read the passage on display alongside them. The text, I discovered upon scanning it attentively, told the story of a married couple that had once shared a deep passion for socializing, dancing, loving one another, and cigarette smoking. Although the wife had given up the latter habit in her fifties, contracting emphysema some time thereafter, the husband found it impossible to desist from puffing. Cancer would ultimately take over his pharynx, throat, and mouth, leaving her to watch him waste away into death. She, the passage explained, would press on for as long as she could, but when the struggle to breathe became too overwhelming, she took to praying to rejoin her love, smiling at the thought of their eventual reunion. I adjusted my stance after coming to the end of the passage to inspect the black- and-white photograph featuring a younger version of the couple, sharply dressed, holding each other intimately in front of a non-descript skyline. -

Adrian Piper

only purposes A SYNTHESISdistribution reviewwide OF INTUITIONSfor or released publication PDF for Not ADRIAN PIPER onlyA SYNTHESIS TO THE MEMORY OF SOL LEWITT purposes distributionOF INTUITIONS reviewwide for or 19652016 released publication PDF for Not CHRISTOPHE CHERIX CORNELIA BUTLER DAVID PLATZKER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK 6 FOREWORD GLENN D. LOWRY ANN PHILBIN OKWUI ENWEZOR 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 12 WHO CALLS THE TUNE? IN AND OUT OF THE HUMMING ROOM CHRISTOPHE CHERIX 30 only ADRIAN PIPER UNITIES DAVID PLATZKER purposes 50 distribution WAKE UP AND GET DOWN reviewwide ADRIAN PIPER’S DIRECT ADDRESS for or CORNELIA BUTLER 72 released THE REAL THING STRANGE Hyundai Card is proud to sponsor Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016 publication ADRIAN PIPER at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. PDF This far-reaching and ambitious exhibition for provides an unparalleled glimpse into the 95 artist’s pioneering oeuvre throughout her Not career of more than fifty years. PLATES Hyundai Card is committed to pursuing the kind of innovative philosophy that is 312 epitomized by Adrian’s artistic practice. As Korea’s foremost issuer of credit cards, PERSONAL CHRONOLOGY Hyundai Card seeks to identify important movements in our culture, society, and ADRIAN PIPER technology, and to engage with them as a way of enriching lives. Whether we’re hosting tomorrow’s cultural pioneers at our 326 stages and art spaces; building libraries of design, travel, music, and cooking for our SELECTED EXHIBITION HISTORY members; or designing credit cards and digital services that are as beautiful as they SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY are functional, Hyundai Card’s most inventive endeavors all draw from the creative well that COMPILED BY TESSA FERREYROS the arts provide. -

Philosophy En Route to Reality: a Bumpy Ride ______

Journal of World Philosophies Intellectual Journeys/106 Philosophy En Route to Reality: A Bumpy Ride ________________________________________ ADRIAN M. S. PIPER APRA Foundation Berlin ([email protected]) My intellectual journey in philosophy proceeded along two mountainous paths that coincided at their base, but forked less than halfway up the incline. The first is that of my philosophical development, a steep but steady and continuous ascent. It began in my family, and accelerated in high school, art school, college, and graduate school. Those foundations propelled my philosophical research into the nature of rationality and its relation to the structure of the self, a long-term project focused on the Kantian and Humean metaethical traditions in Anglo-American analytic philosophy. It would have been impossible to bring this project to completion without the anchor, compass, and conceptual mapping provided by my prior, longstanding involvement in the practice and theory of Vedic philosophy. The second path is that of my professional route through the field of academic philosophy, which branched onto a rocky detour in graduate school, followed by a short but steep ascent, followed next by a much steeper, sustained descent off that road, into the ravine, down in flames, and out of the profession. In order to reach the summit of the first path, I had to reach the nadir of the second. It was the right decision. My yoga practice cushioned my landing. Keywords: Yoga; Vedānta; Sāṁkhya; Vedic philosophy; Spinoza; LSD; art; Kant; Hume; behaviorism; Rawls; metaethics; decision theory; Humean; Kantian My love of analytic philosophy is an inherited trait. My father was a lawyer and lawyer’s son whose Jesuit college training found expression in metaphysical speculation and dialectical arguments with me. -

Perverse Fascination: Medium, Identity, and Performativity In

PERVERSE FASCINATION: MEDIUM, IDENTITY, AND PERFORMATIVITY IN THE ART OF KARA WALKER by JESSICA DITILLIO A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2012 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jessica DiTillio Title: Perverse Fascination: Medium, Identity, and Performativity in the Art of Kara Walker This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Andrew Schulz Chairperson Courtney Thorsson Member Sherwin Simmons Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2012 ii © 2012 Jessica DiTillio iii THESIS ABSTRACT Jessica DiTillio Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture December 2012 Title: Perverse Fascination: Medium, Identity, and Performativity in the Art of Kara Walker Kara Walker is one of the most successful and widely known contemporary African-American artists today—remarkable for her radical engagement with issues of race, gender, and sexuality. Walker is best known for her provocative installations, composed of cut-paper silhouettes depicting fantastic and grotesque scenes of the antebellum South. This thesis examines Walker’s work in silhouettes, text, and video in order to establish the unifying logic that unites her media. Walker’s use of racist stereotypes has incited vehement criticism, and the debate over the political meaning of her work has been worked and reworked in the voluminous literature on her artistic practice. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Adrian Margaret Smith Piper, Born 20

CURRICULUM VITAE Revised March 2011 Adrian Margaret Smith Piper, born 20 September 1948, New York City TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Educational Record ............................................................................................................................. 2 2. Languages ............................................................................................................................................. 2 3. Philosophy Dissertation Topic.......................................................................................................... 2 4. Areas of Special Competence in Philosophy ................................................................................. 2 5. Other Areas of Research Interest in Philosophy ........................................................................... 2 6. Teaching Experience ........................................................................................................................... 2 7. Fellowships and Awards in Philosophy......................................................................................... 3 8. Professional Philosophical Associations......................................................................................... 4 9. Service to the Profession of Philosophy.......................................................................................... 4 10. Invited Papers and Conferences in Philosophy.......................................................................... 4 11. Publications in Philosophy............................................................................................................. -

Adrian Piper's Catalysis (1970-1971)

Cail Lininger University of Toledo Art History Philosophical Examinations of Social Response through Artistic Analysis: Adrian Piper’s Catalysis (1970-1971) Gustav Caillebotte's Paris Street; Rainy Day is, one of the better-known examples of the flaneur; a concept initially thought of by French poet Charles Baudelaire and expanded upon by philosopher Walter Benjamin. The flaneur is the unseen observer, the one who blends in perfectly but through their eyes, the viewer sees truth. In Paris Street, the passersby do not glance over to the focal point that is our perspective, but merely continue on. The well-dressed male in the foreground looks to his right, detached from the scene but observing something beyond the viewer’s eyes. Caillebotte frames the scene perfectly around a modern lamp directly behind the couple in the foreground. The inclusion of the lamp alludes to the changing of the city towards modern time while still maintaining a foothold in the past. By placing the lamp directly in the center, Caillebotte hints at a division within Paris, a city struggling to find its identity. The forced perspective we see allows us as consumers of the scene to observe what is before us. Imagine this rainy day scene in midday Paris directly before us. We see the painting but it is more than a painting, it is a one-way mirror. The separation brought forth by our blending into the scene, the mask, disguise we've donned allows us to participate in the scene before us but also to make observations of the natural state of the bourgeois population before us. -

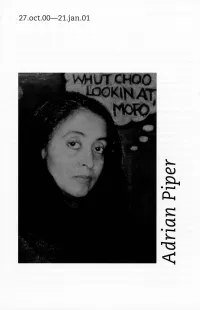

Adrian Piper

Adrian Piper Marking her first explorations in spontaneous and unannounced performance, in 1970, Piper embarked on her seminal Catalysis series in which she physically trans- formed herself into an odd or repulsive person and went out in public to experience The simultaneous presentation of two separately organized exhibitions, Adrian Piper: A the frequently disdainful responses of others. These explorations into xenophobia Retrospective, 1965-2000 and MEDI(t)Ations: Adriari Piper's Videos, Installations, Performances involved such activities as covering her clothing with sticky, wet paint while shop- and Soundworks 1968-1992, provides an in-depth consideration of Piper's artistic produc- ping at Macy's. Though photographs are all that remain of the Catalysis series, the tion during the past thirty-five years and confirms her central position in the trajectory work itself focused on the interaction between the artist and the public, and more of American art. Bringing together more than forty artworks, these exhibitions offer the specifically, on the reaction of the individual to Piper's presence. opportunity to experience Piper's adept use of several media and to consider the com- plex yet resonant concerns that have preoccupied the artist for many years, namely In addition to working as an artist, Piper is a highly respected philosopher and writer. bigotry, stereotyping, and xenophobia. Most important, this retrospective illuminates She was trained in analytic philosophy, and has a particular interest in the work of Piper's unflinching integrity and gives each of us pause to reflect on our personal beliefs Immanuel Kant, specifically his notions of the self and his explorations into what and behaviors.