60 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00224 Art and Language. Blurting, 1973

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martha Wilson Interview Part III the Franklin Furnace Programs

Martha Wilson Interview Part III The Franklin Furnace Programs SANT: When you first organized Franklin Furnace, your main activity was collecting artist books and showing them to the public. How did you start your performance program? WILSON: Our thought was that the same artists who were publishing these books could be invited to read their published stuff, the stuff that we had in the collection. SANT: Isn’t this similar to the many public book readings that happen at many mainstream bookstores Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/dram/article-pdf/49/1 (185)/80/1821483/1054204053327789.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 now? WILSON: But not at the time! No. SANT: Readings in bookstores have been around for quite sometime, haven’t they? I mean, if we go to a different place and time other than New York in the mid-s, such as San Francisco in the mid- s with the Beats, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, and Allen Ginsberg reading Howl ... WILSON: That’s absolutely right. OK. SANT: Were you building on anything like that? Were you aware of such things or were you reinvent- ing the wheel? WILSON: Reinventing the wheel, I would say. I was not focused on the performance program at all because my friend Jacki Apple was my coconspirator and curator. We had already collaborated on a per- formance work in . I was living in Canada at that time. SANT: What had you done together before Franklin Furnace? WILSON: We started corresponding because Lucy Lippard had come to Halifax and introduced us through the catalog to an exhibition that existed only on notecards, about ,. -

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

Elizabeth Anderson's Vita File:///C:/Users/Liz/Documents/Pub/Liz%20Webpages/Vita.Htm

Elizabeth Anderson's Vita file:///C:/Users/Liz/Documents/Pub/Liz%20Webpages/vita.htm ELIZABETH S. ANDERSON John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies Arthur F. Thurnau Professor University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Department of Philosophy Angell Hall 2239 / 435 South State St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1003 Office: 734-763-2118 Fax: 734-763-8071 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~eandersn/ EMPLOYMENT University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 2013-. John Rawls Collegiate Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 2005-. Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, 2004-. Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 1999-2005. Associate Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies, 1993-1999. Adjunct Professor of Law, 1995, 1999, 2000. Assistant Professor of Philosophy, 1987-1993. Swarthmore College, Visiting Instructor in Philosophy, 1985-6. Harvard University, Teaching Fellow, 1983-1985. EDUCATION Harvard University, Department of Philosophy, 1981-1987. A.M. Philosophy, 1984. Ph.D. 1987. Swarthmore College, 1977-1981. B.A. Philosophy with minor in Economics, High Honors, 1981. HONORS, GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS Nominee, Prospect’s World Thinkers 2014 Vice-President/President-Elect, Central Division, American Philosophical Association, 2013-15 Named John Dewey Distinguished University Professor, 2013 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, 2013 ACLS Fellowship, 2013 Michigan Humanities Award, 2013 (declined) Three -

Dissertatie Cvanwinkel

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism van Winkel, C.H. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Winkel, C. H. (2012). During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism. Valiz uitgeverij. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 7 Introduction: During the Exhibition the Gallery Will Be Closed • 1. RESEARCH PARAMETERS This thesis aims to be an original contribution to the critical evaluation of conceptual art (1965-75). It addresses the following questions: What -

Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street Into 'Theatre,' Circa 1964 Tokyo

Performance Paradigm 2 (March 2006) Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street into ‘Theatre,’ Circa 1964 Tokyo Midori Yoshimoto Performance art was an integral part of the urban fabric of Tokyo in the late 1960s. The so- called angura, the Japanese abbreviation for ‘underground’ culture or subculture, which mainly referred to film and theatre, was in full bloom. Most notably, Tenjô Sajiki Theatre, founded by the playwright and film director Terayama Shûji in 1967, and Red Tent, founded by Kara Jûrô also in 1967, ruled the underground world by presenting anti-authoritarian plays full of political commentaries and sexual perversions. The butoh dance, pioneered by Hijikata Tatsumi in the late 1950s, sometimes spilled out onto streets from dance halls. Students’ riots were ubiquitous as well, often inciting more physically violent responses from the state. Street performances, however, were introduced earlier in the 1960s by artists and groups, who are often categorised under Anti-Art, such as the collectives Neo Dada (originally known as Neo Dadaism Organizer; active 1960) and Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension; active 1962-1972). In the beginning of Anti-Art, performances were often by-products of artists’ non-conventional art-making processes in their rebellion against the artistic institutions. Gradually, performance art became an autonomous artistic expression. This emergence of performance art as the primary means of expression for vanguard artists occurred around 1964. A benchmark in this aesthetic turning point was a group exhibition and outdoor performances entitled Off Museum. The recently unearthed film, Aru wakamono-tachi (Some Young People), created by Nagano Chiaki for the Nippon Television Broadcasting in 1964, documents the performance portion of Off Museum, which had been long forgotten in Japanese art history. -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

Oral History Interview with Martha Wilson, 2017 May 17-18

Oral history interview with Martha Wilson, 2017 May 17-18 Funding for this interview was provided by the Lichtenberg Family Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Martha Wilson on May 17 and 18, 2017. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Brooklyn, NY, and was conducted by Liza Zapol for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Martha Wilson and Liza Zapol have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview LIZA ZAPOL: Okay, so this is Liza Zapol for the Archives of American Art, [Smithsonian Institution] oral history program. It's May 17, 2017. And if I can ask you to introduce yourself, please? MARTHA WILSON: My name is Martha Wilson, and I'm going to not hold anything back. LIZA ZAPOL: Thank you. And we're here at your home in Brooklyn. So, if I can just ask you to begin at the beginning— MARTHA WILSON: Okay. LIZA ZAPOL: —as I said. MARTHA WILSON: Okay. LIZA ZAPOL: Where and when were you born? And if you can tell me a little bit about your early memories. MARTHA WILSON: Okay. I was born in Philadelphia in Philadelphia General Hospital or something like that, and raised for the first six years of my life on a houseboat. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

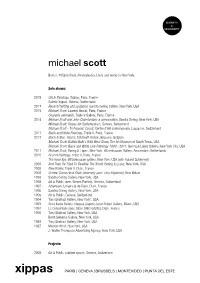

Michael Scott

BIOGRAPHY & BIBLIOGRAPHY michael scott Born in 1958 in Paoli, Pennsylvania. Lives and works in New York. Solo shows: 2018 Circle Paintings, Xippas, Paris, France Galerie Xippas, Geneva, Switzerland 2017 Recent Painting and sculpture, Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Michael Scott, Laurent Strouk, Paris, France Courants alternatifs, Triple V Gallery, Paris, France 2014 Michael Scott and John Chamberlain: a conversation, Sandra Gering, New York, USA Michael Scott, Xippas Art Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland Michael Scott - To Present, Circuit, Centre d’Art contemporain, Lausanne, Switzerland 2013 Black and White Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France 2012 Black & Blue, Galerie Odermatt-Vedovi, Brussels, Belgium Michael Scott: Buffalo Bulb’s Wild West Show, The Art Museum of South Texas, USA Michael Scott: Black and White Line Paintings 1989 - 2011, Gering & López Gallery, New York City, USA 2011 Michael Scott, Gering & López, New York, Witzenhausen Gallery, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2010 Recent Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France The Inner Eye, Witzenhausen gallery, New York, USA (with Roland Schimmel) 2009 And Then He Tried To Swallow The World, Gering & Lopez, New York, USA 2008 New Works, Triple V, Dijon, France 2002 Central Connecticut State University (avec Toby Kilpatrick), New Britain 1999 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1998 Art & Public (avec Steven Parrino), Geneva, Switzerland 1997 Atheneum, Université de Dijon, Dijon, France 1996 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1995 Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland 1994 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York*, USA 1993 Akira Ikeda Gallery, Nagoya (Japon) Jason Rubell Gallery, Miami, USA 1991 Le Consortium (avec Steve DiBenedetto), Dijon, France 1990 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA Brent Sikkema Gallery, New York, USA 1989 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA 1987 Mission West, New York, USA J. -

The Dialogical Imagination: the Conversational Aesthetic of Conceptual Art

THE DIALOGICAL IMAGINATION: THE CONVERSATIONAL AESTHETIC OF CONCEPTUAL ART MICHAEL CORRIS Within the history of avant-garde art there is a recurrent interest in process-based practices. A substantial claim made by proponents of this position argues that process-based practices offer far more scope for the revision of the conventional culture of art than any other type of practice. In the first place, process-based practices dispense with the idea of the production of a material object as the principle aim of art. While there is often a material ‘residue’ associated with process- based art, its status as an autonomous object of art is always questionable. Such objects are more properly understood as props or by-products, and are valued accordingly by the artist (but not, alas, by the critic, curator or collector). Process-based practices themselves raise difficult questions for connoisseurs; there is often no clear notion where to locate the boundary dividing process works from the environment at large. The process-based work of art may not result in an object at all; rather, it could be a performance (scripted or not), an environment or installation, an intervention in a public space, or some sort of social encounter, such as a conversation or an on-going project with a community. The point of all these practices is to radically alter the subject-position of both artist and beholder. By so doing, the very idea of the autonomy of art is placed in question. Once attention and purpose are shifted from the making of what amounts to medium- sized dry goods, so the argument goes, both artist and spectator are liberated. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Schor Moma Moma

12/12/2016 M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 H O M E A B O U T L I N K S Browse: Home / 2016 / December / 09 / M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking CONNE CT 3 Mira's Facebook Page DE CE MBE R 9 , 2 0 1 6 Subscribe in a Reader Subscribe by email M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 miraschor.com The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, TAGS Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and 2016 election Abstract politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and Expressionism ACTUAW poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to. Activism Ana Mendieta Andrea For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some longtime contributors Geyer Andrea Mantegna Anselm and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning Kiefer Barack Obama CalArts craft today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the Cubism DAvid Salle documentary concerns that have the most meaning to them right now. film drawing Edwin Denby Facebook feminism Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will Feminist art appear on A Year of Positive Thinking.