Think Place: Geographies of National Identity in Oman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are You Doing Tomorrow?

WHAT ARE YOU DOING TOMORROW? SHURAMTOURISM.COM BOOK YOUR TRIP WITH US! WWW.SHURAMTOURISM.COM MUSCAT CITY TOUR STOPS HALF DAY FULL DAY STOPS Sultan Qaboos Sultan Qaboos We start off by visiting the exquisite The tour starts like the half day tour. Grand Mosque Grand Mosque Royal Opera House Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque. The tour Royal Opera House Al Alam Palace includes an insight into the different After visiting the Royal Opera House we National Museum Al Alam Palace DURATION Islamic schools and visitors can avail continue drive through Corniche and Muttrah Souq ca.4 hrs of related reading materials at the through old Muscat town to the National DURATION — Grand Mosque Mosque’s library. Afterwards we visit Museum, which offers a wealth of ca.8 hrs the Royal Opera House, Oman’s information about the country’s rich leading global arts and culture centre. — Muscat history, culture and tradition. Enjoy its architectural beauty in a house tour and stroll through the shops Afterwards, we walk a short distance and restaurants in the galleria. to view one of the Sultan’s grand palaces, the Al Alam Palace looking onto We drive through the Corniche and the magnificent 16th century Portu- Old Muscat town to view one of guese Jalali and Mirani Forts. We take the Sultan’s grand palaces, the Al Alam the car to drive to the back of the WWW.SHURAMTOURISM.COM Palace looking onto the magnificent palace for a closer view of the forts. 16th century Portuguese Jalali and Mirani Forts. We take the car to We end our day at Muttrah Souq, where drive to the back of the palace for a you can relish the nostalgic atmosphere closer view of the forts. -

Welcome to Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar Resort a Guide to Etiquette, Climate and Transportation

EXPERIENCE NEW HEIGHTS OF LUXURY WITH AUTHENTIC OMANI HOSPITALITY WELCOME TO ANANTARA AL JABAL AL AKHDAR RESORT A GUIDE TO ETIQUETTE, CLIMATE AND TRANSPORTATION ETIQUETTE As a general courtesy with respect to local customs, it is highly recommended to dress modestly whilst out and about in Oman. We suggest for guests to cover their shoulders and legs (from the knee up), and to avoid form fitting clothing. CLIMATE Al Jabal Al Akhdar is known for its Mediterranean climate. Temperatures drop during winter to below zero degrees Celsius with snow falling at times, and rise in the summer to 28 degrees Celsius. TRANSPORTATION Kindly be informed that you need a 4x4 vehicle to pass by the check point for Al Jabal Al Akhdar, along with your driving license and car registration papers. If you are not driving a 4x4 vehicle, you may park near the check point and request for us to arrange a luxury 4x4 transfer to the resort. Please contact us at tel +968 25218000 for more information. TOP 10 FUN THINGS TO DO IN AL JABAL AL AKHDAR 1. Kids Camping 2. Rock Climbing 3. Wadi of Waterfalls Hike 4. Via Ferrata Mountain Climbing 5. Stargazing 6. Cycling Tours 7. Three Village Adventure Treks 8. Sundown Journey Tour 9. Morning Yoga 10. Archery Lessons DIRECTIONS TO ANANTARA AL JABAL AL AKHDAR RESORT Seeb MUSCAT Muscat International Airport 15 15 Nizwa / Salalah Exit 15 Jabal Akhdar Hotel Samail 15 15 Jabal Akhdar Hotel FROM MUSCAT 172 KM / 2HR 15MIN Use the Northwest expressway out of Muscat heading towards Seeb, and turn off at the Nizwa/Salalah exit and continue following signs towards Izki / Nizwa. -

Al Alama Centre

ALAL AMANAALAMAALAMA CENTRECENTRECENTRE MUSCAT,MUSCAT, SULTANATESULTANATE OFOF OMANOMAN HH AA NN DD BB OO OO KK 0 OUR HISTORY – A UNIQUE LEGACY The name “Al Amana” is Arabic for “bearing trust,” which captures the spirit and legacy of over 115 years of service in Oman. The Centre is the child of the Gulf-wide mission of the Reformed Church in America that began in Oman in 1893. The mission‟s first efforts were in educational work by establishing a school in 1896 that eventually became a coeducational student body of 160 students. The school was closed in 1987 after ninety years of service to the community. The mission was active in many other endeavors, which included beginning a general hospital (the first in Oman), a maternity hospital, a unit for contagious diseases, and a bookshop. With the growth of these initiatives, by the 1950‟s the mission was the largest employer in the private sector in Oman. In the 1970‟s the hospitals were incorporated in the Ministry of Health, and the mission staff worked for the government to assist in the development of its healthcare infrastructure. The mission also established centers for Christian worship in Muscat and Muttrah. It is out of these centers that the contemporary church presence for the expatriate community Oman has grown, now occupying four campuses donated by His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said. After Oman discovered oil, having a newfound wealth with which to modernize, the mission's activities were either concluded or grew into independent initiatives. However, the desire to serve the people of Oman continued. -

Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and Northern Oman Mountains: from Ophiolite Obduction to Continental Collision

GeoArabia, 2014, v. 19, no. 2, p. 135-174 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and northern Oman Mountains: From ophiolite obduction to continental collision Michael P. Searle, Alan G. Cherry, Mohammed Y. Ali and David J.W. Cooper ABSTRACT The tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula in northern Oman shows a transition between the Late Cretaceous ophiolite emplacement related tectonics recorded along the Oman Mountains and Dibba Zone to the SE and the Late Cenozoic continent-continent collision tectonics along the Zagros Mountains in Iran to the northwest. Three stages in the continental collision process have been recognized. Stage one involves the emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite from NE to SW onto the Mid-Permian–Mesozoic passive continental margin of Arabia. The Semail Ophiolite shows a lower ocean ridge axis suite of gabbros, tonalites, trondhjemites and lavas (Geotimes V1 unit) dated by U-Pb zircon between 96.4–95.4 Ma overlain by a post-ridge suite including island-arc related volcanics including boninites formed between 95.4–94.7 Ma (Lasail, V2 unit). The ophiolite obduction process began at 96 Ma with subduction of Triassic–Jurassic oceanic crust to depths of > 40 km to form the amphibolite/granulite facies metamorphic sole along an ENE- dipping subduction zone. U-Pb ages of partial melts in the sole amphibolites (95.6– 94.5 Ma) overlap precisely in age with the ophiolite crustal sequence, implying that subduction was occurring at the same time as the ophiolite was forming. The ophiolite, together with the underlying Haybi and Hawasina thrust sheets, were thrust southwest on top of the Permian–Mesozoic shelf carbonate sequence during the Late Cenomanian–Campanian. -

Key Facts and Figures on Oman

KEY FACTS AND FIGURES ON OMAN 1. Membership in UNESCO: 10 February 1972 2. Membership on the Executive Board: yes (term expires in 2019) 3. Membership on Intergovernmental Committees or Commissions, etc…: Council of the UNESCO International Bureau of Education (Term expires in 2018). Intergovernmental Coordinating Council of the Programme on Man and the Biosphere (Term expires in 2018). Intergovernmental Council of the International Programme for the Development of Communication (Term expires in 2019). Intergovernmental Bioethics Committee (Term expires in 2019). Intergovernmental Council for the Information for Al Programme (Term expires in 2021). Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission 4. Your predecessor’s visits to Oman: 3 13 – 14 May 2014: Global Education for All 22 – 25 January 2011: Official visit 15 – 16 December 2012: Official visit 5. Permanent Delegation to UNESCO H. E. Dr Samira Mohamed Moosa Al Moosa, Ambassador, Permanent Delegate of the Sultanate of Oman to UNESCO (29 September 2011) Staff: Mr Nasser Hamed Salim Al Rawahi, Deputy Permanent Delegate and H. E. Ambassador Musa Bin Jaafar Bin Hassan (Adviser). 6. UNESCO Office in Doha Date of establishment: 1976, Doha (Qatar). Member States serviced: Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and Yemen. Name of Head: Ms. Anna Paolini (Italy), Director of the Doha Office. 7. National Commission for UNESCO . Established in September 1974 . Chairperson: Dr. Madiha bint Ahmed bin Nasser Al Shaibaniya; Minister of Education . Secretary General: Mr Mohammed Saleem Al Yaqoubi since September 2012. 8. Personalities having a relationship with UNESCO: none 9. UNITWIN/UNESCO Chairs: 1 UNESCO Chair in Seafood Biotechnology, established in 2001 at Sultan Qaboos University, Al-Khod. -

Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and Risk

original article Oman Medical Journal [2017], Vol. 32, No. 2 Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and Risk Factor Patterns among Omanis with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Cohort Study Abdul Hakeem Al Rawahi 1*, Patricia Lee2, Zaher A.M. Al Anqoudi3, Ahmed Al Busaidi4, Muna Al Rabaani5, Faisal Al Mahrouqi3 and Ahmed M. Al Busaidi3 1School of Medicine, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia 2School of Medicine, Griffith University, Menzies Health Institute, Queensland, Australia 3Department of Primary Health Care, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Al Dakhiliyah, Oman 4Director of Department of Non-Communicable Diseases, Ministry of Health, Oman 5Al Khoudh Health Centre, Directorate General of Health Services, , Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Objectives: Cardiovascular disease (CVD) represents the leading cause of morbidity Received: 6 November 2016 and mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Its incidence and Accepted: 27 December 2016 risk factor patterns vary widely across different diabetic populations. This study aims Online: to assess the incidence and risk factor patterns of CVD events among Omanis with DOI 10.5001/omj.2017.20 T2DM. Methods: A sample of 2 039 patients with T2DM from a primary care setting, who were free of CVD at beseline (2009−2010) were involved in a retrospective cohort Keywords: Incidence; Risk Factors; study. Socio-demographic data and traditional risk factor assessments at the baseline Cardiovascular Disease; were retrieved from medical records, after which the first CVD outcomes (coronary Coronary Heart Disease; heart disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease) were traced from the baseline to Stroke; Type 2 Diabetes; December 2015, with a median follow-up period of 5.6 years. -

SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT of the FISHERIES SECTOR in OMAN a VISION for SHARED PROSPERITY World Bank Advisory Assignment

Sustainable Management of Public Disclosure Authorized the Fisheries Sector in Oman A Vision for Shared Prosperity World Bank Advisory Assignment Public Disclosure Authorized December 2015 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized World Bank Group Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Wealth Washington D.C. Sultanate of Oman SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF THE FISHERIES SECTOR IN OMAN A VISION FOR SHARED PROSPERITY World Bank Advisory Assignment December 2015 World Bank Group Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Wealth Washington D.C. Sultanate of Oman Contents Acknowledgements . v Foreword . vii CHAPTER 1. Introduction . 1 CHAPTER 2. A Brief History of the Significance of Fisheries in Oman . 7 CHAPTER 3. Policy Support for an Ecologically Sustainable and Profitable Sector . 11 CHAPTER 4. Sustainable Management of Fisheries, Starting with Stakeholder Engagement . 15 CHAPTER 5. Vision 2040: A World-Class Profitable Fisheries Sector . 21 CHAPTER 6. The Next Generation: Employment, Training and Development to Manage and Utilize Fisheries . 27 CHAPTER 7. Charting the Waters: Looking Forward a Quarter Century . 31 iii Boxes Box 1: Five Big Steps towards Realizing Vision 2040 . 6 Box 2: Fifty Years of Fisheries Development Policy . 13 Box 3: Diving for Abalone . 23 Box 4: Replenishing the Fish . 25 Figures Figure 1: Vision 2040 Diagram . 3 Figure 2: Current Status of Key Fish Stocks in Oman . 12 Figure 3: New Fisheries Management Cycle . 29 Tables Table 1: Classification of Key Stakeholders in the Fisheries Sector . 16 Table 2: SWOT Analysis from Stakeholder Engagement (October 2014) . 18 iv Sustainable Management of the Fisheries Sector in Oman – A Vision for Shared Prosperity Acknowledgements he authors wish to thank H . -

Draft Provisonal Agenda and Time-Table

IT/GB-5/13/Inf. 2 June 2013 FIFTH SESSION OF THE GOVERNING BODY Muscat, Oman, 24-28 September 2013 NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Last Update: 15 July 2013 1. MEETING ARRANGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 DATE AND PLACE OF THE MEETING ........................................................................................................... 2 COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE SECRETARIAT ........................................................................................... 2 INVITATION LETTERS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ADMISSION OF PARTICIPANTS .................................................................................................................... 2 States that are Contracting Parties ......................................................................................................... 2 States that are not Contracting Parties................................................................................................... 3 Other international bodies or agencies .................................................................................................. 3 2. REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................................. 3 ONLINE PRE-REGISTRATION ..................................................................................................................... -

Driving Instructions

Driving Instructions Muscat – Alila Jabal Akhdar Use the northwest expressway out of Muscat heading towards Seeb, and turn off at the Nizwa/Salalah exit and continue following signs towards Izki / Nizwa 180 km/ 2 hr 30min 1. Take Route 15 towards Nizwa / Salalah and take the Nizwa / Salalah exit 120 km 2. Continue towards Izki and take the exit of Birkat Al Mouz / Al Jabal Al Akhdar 4.5 km 3. Turn left at the T-junction 1.5 km 4. Turn left at the next T-junction 1.3 km 5. At the roundabout, turn right 0.8 km 6. Continue driving until you reach Al Jabal Al Akhdar direction, turn left (there is a 17th century fortress – Bayt Al Ridaydah) 0.3 km 7. Drive along until you reach the Police Check Point 6.2 km *Please be informed that you need a 4x4 car to pass by showing driving license as well as car registration paper 8. After driving up the long and steep winding road you will pass the Jabal Akhdar Hotel and take the right turn. Please look at the small Alila sign on the corner 26.2 km 9. Continue driving towards village Al Roos, turn right at the sign for Al Roos 10.5 km 10. Keep driving and follow the road. You will see Alila gate ahead on the left side 9.2 km Safe travels and see you at the hotel! 2h 30 min Al Ain (UAE) – Alila Jabal Akhdar Driving Instructions 1. Starting from Al Ain highway, take the exit of Jabal Hafit border towards Sultanate of Oman and keep driving towards Dhank City approx. -

Sustainable Destination Management Strategies in the OIC Member Countries

Sustainable Destination Management Strategies in the OIC Member Countries COMCEC COORDINATION OFFICE February 2019 Standing Committee for Economic and Commercial Cooperation of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (COMCEC) Sustainable Destination Management Strategies in the OIC Member Countries COMCEC COORDINATION OFFICE February 2019 This report has been commissioned by the COMCEC Coordination Office to DinarStandard. Views and opinions expressed in the report are solely those of the authors and do not represent the official views of the COMCEC Coordination Office (CCO) or the Member Countries of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the COMCEC/CCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its political regime or frontiers or boundaries. Designations such as “developed,” “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the state reached by a particular country or area in the development process. The mention of firm names or commercial products does not imply endorsement by COMCEC and/or CCO. The final version of the report is available at the COMCEC website.* Excerpts from the report can be made as long as references are provided. All intellectual and industrial property rights for the report belong to the CCO. This report is for individual use and it shall not be used for commercial purposes. Except for purposes of individual use, this report shall not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying, CD recording, or by any physical or electronic reproduction system, or translated and provided to the access of any subscriber through electronic means for commercial purposes without the permission of the CCO. -

Ambassador Richard W. Boehm

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR RICHARD W. BOEHM Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 27, 1994 Copyright 199 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Queen New York 1926 (amaica High School Army armored division Germany 194,-1946 Adelphi .ollege graduated 19,0 0ngland France 1941-1949 2erits of G.I. Bill Prentice Hall Publishing .ompany 2utual Insurance .ompany Foreign Service 06amination process Appointed to the Foreign Service December 19,4 2otivations to enter the Foreign Service New Division 19,,-19,6 Henry Suydam head Role of Division News-tickers service 8iaison with the bureau of Near 0astern Affairs 9sort of assistant spokesman: Department of State;s relationship with the press .old war issues Foreign Service Institute 19,6 A <100 course .onsular course Schott 2c8eod & Frank Auerbach Naha Okinawa 19,6-19,1 (unior vice-consul Organization people in the consular unit 8iving in Okinawa Report on 9Revisionist sentiment among the Okinawans: Reaction of American military command to report 1 Hamburg West Germany 19,9 Assistant General Service Officer German language school Frankfurt West Berlin West Germany 19,9-1962 0conomic Section 19,9-1960 Driving on the autobahn to West Berlin Khrushchev;s ultimatum 0conomy population government of West Berlin Prohibited manufacture and sales of goods for military use Question of dual use items French position Access to 0ast Berlin No contact with 0ast German authorities A.S. policy on 0ast Germany 0conomic developments in 0ast Germany 9Inter-Bonal Trade: Disparity between 0ast and West German economic situations Possibility of Soviet attack on West Berlin fear of nuclear war Disparity of Soviet attack on West Berlin fear of nuclear war .oncerns about change in A.S. -

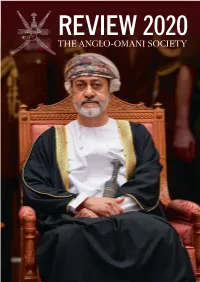

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families.