A Quick Tour of Nematode Diversity and the Backbone of Nematode Phylogeny* §

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastrointestinal Helminthic Parasites of Habituated Wild Chimpanzees

Aus dem Institut für Parasitologie und Tropenveterinärmedizin des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of habituated wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Taï NP, Côte d’Ivoire − including characterization of cultured helminth developmental stages using genetic markers Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Veterinärmedizin an der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Sonja Metzger Tierärztin aus München Berlin 2014 Journal-Nr.: 3727 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zentek Erster Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Zweiter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer Dritter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Achim Gruber Deskriptoren (nach CAB-Thesaurus): chimpanzees, helminths, host parasite relationships, fecal examination, characterization, developmental stages, ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial DNA Tag der Promotion: 10.06.2015 Contents I INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------- 1- 4 I.1 Background 1- 3 I.2 Study objectives 4 II LITERATURE OVERVIEW --------------------------------------- 5- 37 II.1 Taï National Park 5- 7 II.1.1 Location and climate 5- 6 II.1.2 Vegetation and fauna 6 II.1.3 Human pressure and impact on the park 7 II.2 Chimpanzees 7- 12 II.2.1 Status 7 II.2.2 Group sizes and composition 7- 9 II.2.3 Territories and ranging behavior 9 II.2.4 Diet and hunting behavior 9- 10 II.2.5 Contact with humans 10 II.2.6 -

From South Africa

First report of the isolation of entomopathogenic AUTHORS: nematode Steinernema australe (Rhabditida: Tiisetso E. Lephoto1 Vincent M. Gray1 Steinernematidae) from South Africa AFFILIATION: 1 Department of Microbiology and A survey was conducted in Walkerville, south of Johannesburg (Gauteng, South Africa) between 2012 Biotechnology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and 2016 to ascertain the diversity of entomopathogenic nematodes in the area. Entomopathogenic South Africa nematodes are soil-dwelling microscopic worms with the ability to infect and kill insects, and thus serve as eco-friendly control agents for problem insects in agriculture. Steinernematids were recovered in 1 out CORRESPONDENCE TO: Tiisetso Lephoto of 80 soil samples from uncultivated grassland; soil was characterised as loamy. The entomopathogenic nematodes were identified using molecular and morphological techniques. The isolate was identified as EMAIL: Steinernema australe. This report is the first of Steinernema australe in South Africa. S. australe was first [email protected] isolated worldwide from a soil sample obtained from the beach on Isla Magdalena – an island in the Pacific DATES: Ocean, 2 km from mainland Chile. Received: 31 Jan. 2019 Revised: 21 May 2019 Significance: Accepted: 26 Aug. 2019 • Entomopathogenic nematodes are only parasitic to insects and are therefore important in agriculture Published: 27 Nov. 2019 as they can serve as eco-friendly biopesticides to control problem insects without effects on the environment, humans and other animals, unlike chemical pesticides. HOW TO CITE: Lephoto TE, Gray VM. First report of the isolation of entomopathogenic Introduction nematode Steinernema australe (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) Entomopathogenic nematodes are one of the most studied microscopic species of nematodes because of their from South Africa. -

(Musa AAA) As Influenced by Agronomic Factors

Institut für Nutzpflanzenwissenschaften und Ressourcenschutz der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn The importance of the antagonistic potential in the management of populations of plant-parasitic nematodes in banana (Musa AAA) as influenced by agronomic factors Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften (Dr. agr.) der Hohen Landwirtschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich- Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt am 15. Juni 2010 von Anthony Barry Pattison South Johnstone Australia Referent: Prof. Dr. R.A. Sikora Korreferent: Prof. Dr. H. Goldbach Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 15 September 2011 Erscheinungsjahr: 2011 Dedication: This work is dedicated to the support given to me by family and friends. Especially to my wife Susan, daughters Katie and Emily for their patience while I completed this work. Also, to the friends I have made along the way, who have helped to make the world a little smaller. Summary Dr.agr. Thesis: A Pattison The importance of the antagonistic potential in the management of populations of plant-parasitic nematodes in banana ( Musa AAA) as influenced by agronomic factors Plant-parasitic nematodes are a major obstacle to sustainable banana production around the world. The use of organic amendments was investigated as one method to stimulate organisms that are antagonistic to plant-parasitic nematodes. Nine different amendments; mill mud, mill ash (by-products from processing sugarcane), biosolids, municipal waste (MW) compost, banana residue, grass hay, legume hay, molasses and calcium silicate (CaSi) were applied in a glasshouse experiment. Significant suppression of Radopholus similis occurred in soils amended with legume hay, grass hay, banana residue and mill mud relative to untreated soil, which increased the nematode community structure index, indicating greater potential for predation. -

Repertoire and Evolution of Mirna Genes in Four Divergent Nematode Species

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Resource Repertoire and evolution of miRNA genes in four divergent nematode species Elzo de Wit,1,3 Sam E.V. Linsen,1,3 Edwin Cuppen,1,2,4 and Eugene Berezikov1,2,4 1Hubrecht Institute-KNAW and University Medical Center Utrecht, Cancer Genomics Center, Utrecht 3584 CT, The Netherlands; 2InteRNA Genomics B.V., Bilthoven 3723 MB, The Netherlands miRNAs are ;22-nt RNA molecules that play important roles in post-transcriptional regulation. We have performed small RNA sequencing in the nematodes Caenorhabditis elegans, C. briggsae, C. remanei, and Pristionchus pacificus, which have diverged up to 400 million years ago, to establish the repertoire and evolutionary dynamics of miRNAs in these species. In addition to previously known miRNA genes from C. elegans and C. briggsae we demonstrate expression of many of their homologs in C. remanei and P. pacificus, and identified in total more than 100 novel expressed miRNA genes, the majority of which belong to P. pacificus. Interestingly, more than half of all identified miRNA genes are conserved at the seed level in all four nematode species, whereas only a few miRNAs appear to be species specific. In our compendium of miRNAs we observed evidence for known mechanisms of miRNA evolution including antisense transcription and arm switching, as well as miRNA family expansion through gene duplication. In addition, we identified a novel mode of miRNA evolution, termed ‘‘hairpin shifting,’’ in which an alternative hairpin is formed with up- or downstream sequences, leading to shifting of the hairpin and creation of novel miRNA* species. -

Biology Two DOL38 - 41

III. Phylum Platyhelminthes A. General characteristics All About Worms! 1. flat worms a. distinct head & tail ends 2. bilateral symmetry 3. habitat = free-living aquatic or parasitic *a. Parasite = heterotroph that gets its nutrients from the living organisms in/on which they live Ph. Platyhelminthes Ph. Nematoda Ph. Annelida 4. motile 5. carnivores or detritivores 6. reproduce sexually & asexually Biology Two DOL38 - 41 7/4/2016 B. Anatomy 3. Simple nervous system 1. have 3 body layers w/ true tissues a. brain-like ganglia in head & organs b. 2 longitudinal nerves with a. inner = endoderm transverse nerves across body b. middle = mesoderm 4. Lack respiratory, circulatory systems c. outer = ectoderm 5. Parasitic forms lack digestive & excretory systems 2. are acoelomates - lack a coelom around internal organs a. use diffusion to supply needs from host organisms a. digestive tract is formed of endoderm 6. Planaria anat. 7. Tapeworm anat. a. flat body w/ arrow-shaped head & a. head = scolex tapered tail 1) has hooks to help hold onto host b. light-sensitive eyespots on head 2) has suckers to ingest food c. body covered in cilia & mucus to aid b. body segments = proglottids movement 1) new ones form right behind head d. digestive tract only open at mouth 2) each segment produces gametes 1) in center of ventral surface 3) each houses excretory organs 2) used for feeding, excretion C. Physiology 1. Digestion (free-living) a. pharynx extends out of mouth b. sucks food into intestines for digestion c. excretory pores & mouth/pharynx remove wastes 2. Reproduction varies a. Sexual for free-living (& some parasites) 1) hermaphrodites a) cross-fertilize or self-fertilize internally b. -

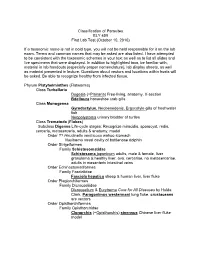

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

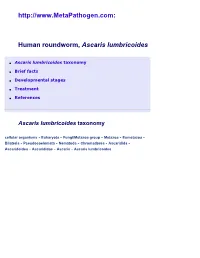

Ascaris Lumbricoides, Roundworm, Causative Agent Of

http://www.MetaPathogen.com: Human roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides ● Ascaris lumbricoides taxonomy ● Brief facts ● Developmental stages ● Treatment ● References Ascaris lumbricoides taxonomy cellular organisms - Eukaryota - Fungi/Metazoa group - Metazoa - Eumetazoa - Bilateria - Pseudocoelomata - Nematoda - Chromadorea - Ascaridida - Ascaridoidea - Ascarididae - Ascaris - Ascaris lumbricoides Brief facts ● Together with human hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus also described at MetaPathogen) and whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), Ascaris lumbricoides (human roundworms) belong to a group of so-called soil-transmitted helminths that represent one of the world's most important causes of physical and intellectual growth retardation. ● Today, ascariasis is among the most important tropical diseases in humans with more than billion infected people world-wide. Ascariasis is mostly seen in tropical and subtropical countries because of warm and humid conditions that facilitate development and survival of eggs. The majority of infections occur in Asia (up to 73%), followed by Africa (~12%) and Latin America (~8%). ● Ascaris lumbricoides is one of six worms listed and named by Linnaeus. Its name has remained unchanged up to date. ● Ascariasis is an ancient infection, and A. lumbricoides have been found in human remains from Peru dating as early as 2277 BC. There are records of A. lumbricoides in Egyptian mummy dating from 1938 to 1600 BC. Despite of long history of awareness and scientific observations, the parasite's life cycle in humans, including the migration of the larval stages around the body, was discovered only in 1922 by a Japanese pediatrician, Shimesu Koino. ● Unlike the hookworm, whose third-stage (L3) larvae actively penetrate skin, A. lumbricoides (as well as T. trichiura) is transmitted passively within the eggs after being swallowed by the host as a result of fecal contamination. -

Modeling the Ballistic-To-Diffusive Transition in Nematode Motility

Modeling the ballistic-to-diffusive transition in nematode motility reveals variation in exploratory behavior across species Stephen J. Helms∗1, W. Mathijs Rozemuller∗1, Antonio Carlos Costa∗2, Leon Avery3, Greg J. Stephens2,4, and Thomas S. Shimizu y1 1AMOLF Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2Dept. of Physics & Astronomy, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 3Dept. of Physiology and Biophysics, Virginia Commonwealth Univ., Richmond, VA, USA 4Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, Onna-son, Okinawa, Japan Abstract A quantitative understanding of organism-level behavior requires pre- dictive models that can capture the richness of behavioral phenotypes, yet are simple enough to connect with underlying mechanistic processes. Here we investigate the motile behavior of nematodes at the level of their trans- lational motion on surfaces driven by undulatory propulsion. We broadly sample the nematode behavioral repertoire by measuring motile trajecto- ries of the canonical lab strain C. elegans N2 as well as wild strains and distant species. We focus on trajectory dynamics over timescales span- ning the transition from ballistic (straight) to diffusive (random) move- ment and find that salient features of the motility statistics are captured by a random walk model with independent dynamics in the speed, bear- arXiv:1501.00481v3 [q-bio.NC] 24 Mar 2019 ing and reversal events. We show that the model parameters vary among species in a correlated, low-dimensional manner suggestive of a common mode of behavioral control and a trade-off between exploration and ex- ploitation. The distribution of phenotypes along this primary mode of variation reveals that not only the mean but also the variance varies con- siderably across strains, suggesting that these nematode lineages employ contrasting \bet-hedging" strategies for foraging. -

Monophyly of Clade III Nematodes Is Not Supported by Phylogenetic Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Monophyly of clade III nematodes is not supported by phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7509r5vp Journal BMC Genomics, 12(1) ISSN 1471-2164 Authors Park, Joong-Ki Sultana, Tahera Lee, Sang-Hwa et al. Publication Date 2011-08-03 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-392 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Park et al. BMC Genomics 2011, 12:392 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/12/392 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Monophyly of clade III nematodes is not supported by phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences Joong-Ki Park1*, Tahera Sultana2, Sang-Hwa Lee3, Seokha Kang4, Hyong Kyu Kim5, Gi-Sik Min2, Keeseon S Eom6 and Steven A Nadler7 Abstract Background: The orders Ascaridida, Oxyurida, and Spirurida represent major components of zooparasitic nematode diversity, including many species of veterinary and medical importance. Phylum-wide nematode phylogenetic hypotheses have mainly been based on nuclear rDNA sequences, but more recently complete mitochondrial (mtDNA) gene sequences have provided another source of molecular information to evaluate relationships. Although there is much agreement between nuclear rDNA and mtDNA phylogenies, relationships among certain major clades are different. In this study we report that mtDNA sequences do not support the monophyly of Ascaridida, Oxyurida and Spirurida (clade III) in contrast to results for nuclear rDNA. Results from mtDNA genomes show promise as an additional independently evolving genome for developing phylogenetic hypotheses for nematodes, although substantially increased taxon sampling is needed for enhanced comparative value with nuclear rDNA. -

Nematodes and Agriculture in Continental Argentina

Fundam. appl. NemalOl., 1997.20 (6), 521-539 Forum article NEMATODES AND AGRICULTURE IN CONTINENTAL ARGENTINA. AN OVERVIEW Marcelo E. DOUCET and Marîa M.A. DE DOUCET Laboratorio de Nematologia, Centra de Zoologia Aplicada, Fant/tad de Cien.cias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Cordoba, Casilla df Correo 122, 5000 C6rdoba, Argentina. Acceplecl for publication 5 November 1996. Summary - In Argentina, soil nematodes constitute a diverse group of invertebrates. This widely distributed group incJudes more than twO hundred currently valid species, among which the plant-parasitic and entomopathogenic nematodes are the most remarkable. The former includes species that cause damages to certain crops (mainly MeloicU:igyne spp, Nacobbus aberrans, Ditylenchus dipsaci, Tylenchulus semipenetrans, and Xiphinema index), the latter inc1udes various species of the Mermithidae family, and also the genera Steinernema and Helerorhabditis. There are few full-time nematologists in the country, and they work on taxonomy, distribution, host-parasite relationships, control, and different aspects of the biology of the major species. Due tO the importance of these organisms and the scarcity of information existing in Argentina about them, nematology can be considered a promising field for basic and applied research. Résumé - Les nématodes et l'agriculture en Argentine. Un aperçu général - Les nématodes du sol représentent en Argentine un groupe très diversifiè. Ayant une vaste répartition géographique, il comprend actuellement plus de deux cents espèces, celles parasitant les plantes et les insectes étant considèrées comme les plus importantes. Les espèces du genre Me/oi dogyne, ainsi que Nacobbus aberrans, Dùylenchus dipsaci, Tylenchulus semipenetrans et Xiphinema index représentent un réel danger pour certaines cultures. -

The Types of Supplements in the Family Tobrilidae (Nematoda, Enoplia) Alexander V

Russian Journal of Nematology, 2015, 23 (2), 81 – 90 The types of supplements in the family Tobrilidae (Nematoda, Enoplia) Alexander V. Shoshin1, Ekaterina A. Shoshina1 and Julia K. Zograf2, 3 1Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya Naberezhnaya 1, 199034, Saint Petersburg, Russia 2A.V. Zhirmunsky Institute of Marine Biology, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Paltchevsky Street 17, 690041, Vladivostok, Russia 3Far Eastern Federal University, Sukhanova Street 8, 690090, Vladivostok, Russia e-mail: [email protected] Accepted for publication 11 October 2015 Summary. The structure of supplementary organs and buccal cavity are the main diagnostic features for identification of Tobrilidae species. Four main supplement types can be distinguished among representatives of this family. Type I supplements are typical for Tobrilus, Lamuania and Semitobrilus and are characterised by their small size and slightly protruding external part. There are two variations of the type I supplement structure: amabilis and gracilis. Type II is typical for several Eutobrilus species (E. peregrinator, E. prodigiosus, E. strenuus, E. nothus). These supplements are very similar to the type I supplements but are characterised in having a highly protruding torus with numerous microthorns and a bulbulus situated at the base of the ampoule. Type III is typical for Eutobrilus species from the Tobrilini tribe, i.e., E. graciliformes, E. papilicaudatus and E. differtus, and Mesotobrilus spp. from the Paratrilobini tribe and is characterised by a well-defined cap and a bulbulus situated at the base of the ampoule. Type IV is observed in the majority of Eutobrilus, Paratrilobus, Brevitobrilus and Neotobrilus and is the most complex supplement type with a mobile cap and an apical bulbulus. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying