The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: 12 Myths Debunked Adam N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presidential Administration Under Trump Daniel A

Presidential Administration Under Trump Daniel A. Farber1 Anne Joseph O’Connell2 I. Introduction [I would widen the Introduction: focusing on the problem of what kind of president Donald Trump is and what the implications are. The descriptive and normative angles do not seem to have easy answers. There is a considerable literature in political science and law on positive/descriptive theories of the president. Kagan provides just one, but an important one. And there is much ink spilled on the legal dimensions. I propose that after flagging the issue, the Introduction would provide some key aspects of Trump as president, maybe even through a few bullet points conveying examples, raise key normative questions, and then lay out a roadmap for the article. One thing to address is what ways we think Trump is unique for a study of the President and for the study of Administrative Law, if at all.] [We should draft this after we have other sections done.] Though the Presidency has been a perennial topic in the legal literature, Justice Elena Kagan, in her earlier career as an academic, penned an enormously influential 2001 article about the increasingly dominant role of the President in regulation, at the expense of the autonomy of administrative agencies.3 The article’s thesis, simply stated, was that “[w]e live in an era of presidential administration.”, by 1 Sho Sato Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. 2 George Johnson Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. 3 Elena Kagan, Presidential Administration, 114 HARV. L. REV. 2245 (2001). -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM 02/12/21 Friday This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. Lincoln Project Faces Exodus of Advisers Amid Sexual Harassment Coverup Scandal by Morgan Artvukhina Donald Trump was a political outsider in the 2016 US presidential election, and many Republicans refused to accept him as one of their own, dubbing themselves "never-Trump" Republicans. When he sought re-election in 2020, the group rallied in support of his Democratic challenger, now the US president, Joe Biden. An increasing number of senior figures in the never-Trump political action committee The Lincoln Project (TLP) have announced they are leaving, with three people saying Friday they were calling it quits in the wake of a sexual assault scandal involving co-founder John Weaver. "I've always been transparent about all my affiliations, as I am now: I told TLP leadership yesterday that I'm stepping down as an unpaid adviser as they sort this out and decide their future direction and organization," Tom Nichols, a “never-Trump” Republican who supported the group’s effort to rally conservative support for US President Joe Biden in the 2020 election, tweeted on Friday afternoon. Nichols was joined by another adviser, Kurt Bardella and by Navvera Hag, who hosted the PAC’s online show “The Lincoln Report.” Late on Friday, Lincoln Project co-founder Steve Schmidt reportedly announced his resignation following accusations from PAC employees that he handled the harassment scandal poorly, according to the Daily Beast. -

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View Document

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View document: The notion that my social media identifier should have anything to do with entering the country is a shockingly Nazi like rule. The only thing that this could facilitate anyway is trial by association - something that is known to ensnare innocent people, and not work. What is more this type of thing is repugnant to a free society. The fact that it is optional doesn't help - as we know that this "optional" thing will soon become not-optional. If your intent was to keep it optional - why even bother? Most importantly the rules that we adopt will tend to get adopted by other countries and frankly I don't trust China, India, Turkey or even France all countries that I regularly travel to from the US with this information. We instead should be a beacon for freedom - and we fail in our duty when we try this sort of thing. Asking for social media identifier should not be allowed here or anywhere. Comment Submitted by David Cain Comment View document: I am firmly OPPOSED to the inclusion of a request - even a voluntary one - for social media profiles on the I-94 form. The government should NOT be allowed to dip into users' social media activity, absent probable cause to suspect a crime has been committed. Bad actors are not likely to honor the request. Honest citizens are likely to fill it in out of inertia. This means that the pool of data that is built and retained will serve as a fishing pond for a government looking to control and exploit regular citizens. -

Celebrity Polling Firm Rates Spicer 13 out of 100

Celebrity polling firm rates Spicer 13 out of 100 During his time in the Trump administration, former White House press secretary Sean Spicer had a testy relationship with the news media that played out from the podium before the American public. | J. Scott Applewhite/AP A talent agency provided POLITICO with the data used by TV executives to assess audience appeal. The former Trump spokesman bombed. By TARA PALMERI 09/06/2017 After a beleaguered six-month run as White House press secretary, Sean Spicer has been shopping his brand for television, book and speaking deals in recent weeks. The latest findings of a celebrity-popularity poll, however, may show why he is a tough sell. Sixty-four percent of respondents in the survey from E-Score, a polling company used by major talent agencies and TV executives to assess celebrities, had a negative opinion about Spicer, compared with 36 percent who liked him. Spicer’s overall score — based on awareness, appeal and attributes — was 13. In contrast, Oprah Winfrey clocked in at an overall 96 while Megyn Kelly, the former Fox News journalist who now hosts the NBC newsmagazine “Sunday Night With Megyn Kelly,” rated a 52. The gap in those numbers isn’t totally surprising. During his time in the Trump administration, Spicer had a testy relationship with the news media that played out from the podium before the American public. Also, political figures typically score lower in celebrity market research, and the survey was conducted in April, two months before Spicer resigned his White House post. “That’s a very high negative score,” Randy Parker, E-Score’s director of marketing, said of Spicer’s appeal. -

Polish Duda Rises Over Brussels the Election of a Euroskeptical President Raises Pressing Questions About Warsaw’S Sway in the EU

VOL. 1 NO. 6 THURSDAY, MAY 28, 2015 POLITICO.EU Polish Duda rises over Brussels The election of a Euroskeptical president raises pressing questions about Warsaw’s sway in the EU By JAN CIENSKI factored in a second term for in- of a more socially conservative — into parliamentary elections Warsaw as the leading EU power cumbent Bronisław Komorows- and Euroskeptical strand of Pol- in autumn. Komorowski’s loss east of Germany. The surprise victory of Andrzej ki. Dismissed as an unknown and ish politics. reflected voter fatigue with his “Duda is a representative of Duda in Poland’s presidential long-shot, Duda triumphed in The 43-year-old lawyer comes centrist Civic Platform (PO), the Kaczyński movement, which runo was greeted with shock Sunday’s elections by three per- from the Law and Justice (PiS) which has ruled Poland since was very critical of the common in Brussels, and raised pressing centage points, bloc of Jarosław Kaczyński, a 2007 and comes into the election European approach and has a questions about the future of heralding former prime minister who campaign on a weaker foot. This very nationalistic background,” Warsaw’s policies toward as well the re- will lead the party — now unexpected political shift is also said Manfred Weber, president as influence in the EU. sur- brimming with momen- forcing a rethink of Poland by its The European capital had long gence tum and confidence main EU partners, which view POLAND: PAGE 21 The reign The Queen in Spain is does CREDIT no longer Cameron’s on the wane bidding King Felipe and By BEN JUDAH Queen Letizia, LONDON — Queen Elizabeth II made clear Wednesday that the a power parliament will be dominated by Prime Minister David Cameron’s couple for a quest for a new, long-term consti- tutional settlement for Britain. -

Ashika Singh ([email protected]) DEBEVOISE & PLIMPTON LLP 919 Third Avenue New York, NY 10022 Tel.: (212) 909-6000 Attorneys for Open Society Justice Initiative

Case 1:19-cv-01329-PAE Document 1 Filed 02/12/19 Page 1 of 17 Catherine Amirfar ([email protected]) Ashika Singh ([email protected]) DEBEVOISE & PLIMPTON LLP 919 Third Avenue New York, NY 10022 Tel.: (212) 909-6000 Attorneys for Open Society Justice Initiative UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK OPEN SOCIETY JUSTICE INITIATIVE, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. _____________ DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE and DEPARTMENT OF STATE, Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE RELIEF INTRODUCTION 1. This is an action under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. § 552. In this lawsuit, Plaintiff seeks injunctive relief to compel Defendants U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”), including its component the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”), and U.S. Department of State (“DOS”) to immediately release records related to the killing of U.S. resident Jamal Khashoggi in response to Plaintiff’s properly filed FOIA requests. 2. Plaintiff is bringing this action because, to date, Defendants have not issued determinations on Plaintiff’s requests within the statutorily-prescribed time limit nor disclosed any responsive records. Case 1:19-cv-01329-PAE Document 1 Filed 02/12/19 Page 2 of 17 JURISDICTION AND VENUE 3. This Court has both subject matter jurisdiction over this action and personal jurisdiction over the parties pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B). This Court also has jurisdiction over this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1331. Venue lies in this district under 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B) because Plaintiff’s principal place of business is in this district. -

We're Pleased to Announce the New Playbook Team, Which

Hi all -- We’re pleased to announce the new Playbook team, which takes the reins on Jan. 19 — just as one administration leaves power and a new one enters office. Before we get to the juicier parts, a brief note on the mission. Since its inception, Playbook is what Washington wakes up with. It sets the agenda for the political day and days ahead and breaks news and makes sense of it. It dishes a steady dose of insider nuggets and intrigue for and about power players here. But as the town has changed in the years since Playbook launched as a one-writer operation, so too has the ambition of this, our flagship product. Playbook 3.0 has to take its community of readers inside the backrooms of decision-making for all the important power centers — from the West Wing and congressional leaders’ offices to deep inside key agencies and the K Street conversation, and ultimately to the campaign trail. It has to bring them to the front lines of the big legislative battles dominating the headlines, and how they might play out. It has to focus on the people driving the action here— their egos, insecurities and peccadillos. It has to understand the establishment as well as the next generation of power players in a changing, more diverse capital. And oh, Playbook isn’t just the anchor morning newsletter; it engages with the DC community in many other ways, some that exist (such as events, afternoon newsletters, the audio brief) and others that we’ll roll out in the coming weeks. -

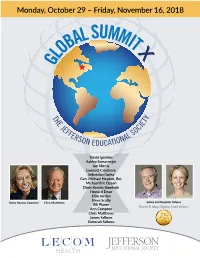

Globalsummit X

Event Sponsors Monday, October 29 – Friday, November 16, 2018 Thank You LSUMM Platinum BA IT LO X G Gold Silver Bronze Copper T H Y E T IE JE C GOHRS F O p: (814) 455-0629 · f: (814) 454-2718 FE S RS AL Patron Sponsors ON EDUCATION David Ignatius Personal Patrons Ashley Swearengin Ian Morris Maureen Plunkett and Family Anonymous Jefferson Trustee Leonard Calabrese Sebastian Gorka Gen. Michael Hayden, Ret. Michael Eric Dyson Thomas Jefferson believed a citizenry that was educated on issues and shared its ideas through public discourse had the power to make a difference in the world. Doris Kearns Goodwin Howard Dean The Jefferson Educational Society of Erie is a strong proponent of that belief, offering courses, seminars,and lectures that explain the ideas that formed the past, assist in exploring the present,and offer guidance in creating the future of the Erie region. Elise Jordan Steve Scully Doris Kearns Goodwin Chris Matthews James and Deborah Fallows Bill Plante Thomas B. Hagen Dignitas Award Winners 3207 State Street Ann Compton Erie, Pennsylvania Chris Matthews 16508-2821 James Fallows XXDeborah Fallows Dear Friends: Welcome to the Jefferson Educational Society’s Global Summit X! This important lecture series could not come at a more opportune time, as we address some of the key issues facing the Erie community, our country, and the world. As this event enters its 10th year, we can reflect proudly on last year’s summit, which marked the first time the Global Summit stretched into a third week! We heard nine great presentations from 13 of the most respected scholars, writers, and leaders in their respective fields. -

Technology Companies As Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees in 17-2231 (L), 17-2232, 17-2233 and Appellants in 17-2240 ______

Appeal: 17-2231 Doc: 112-1 Filed: 11/17/2017 Pg: 1 of 56 Nos. 17-2231 (L), 17-2232, 17-2233, 17-2240 (Consolidated) In the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ______________________________ INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE ASSISTANCE PROJECT, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, and ALLAN HAKKY and SAMANEH TAKALOO, Plaintiffs, – v. – DONALD J. TRUMP, et al., Defendants-Appellants. ______________________________ No. 17-2231 (L) On Cross-Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Maryland, Southern Division [Caption continued on inside cover] ______________________________ BRIEF OF TECHNOLOGY COMPANIES AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES IN 17-2231 (L), 17-2232, 17-2233 AND APPELLANTS IN 17-2240 ______________________________ Andrew J. Pincus Paul W. Hughes John T. Lewis MAYER BROWN LLP 1999 K Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 (202) 263-3000 Counsel for Amici Curiae Appeal: 17-2231 Doc: 112-1 Filed: 11/17/2017 Pg: 2 of 56 ______________________________ No. 17-2232 ______________________________ IRANIAN ALLIANCES ACROSS BORDERS, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, – v. – DONALD J. TRUMP, et al., Defendants-Appellants. ______________________________ No. 17-2233 ______________________________ EBLAL ZAKZOK, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, – v. – DONALD J. TRUMP, et al., Defendants-Appellants. ______________________________ No. 17-2240 ______________________________ INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE ASSISTANCE PROJECT, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants and PAUL HARRISON, et al., Plaintiffs, – v. – DONALD J. TRUMP, et al., Defendants-Appellees. ii Appeal: 17-2231 Doc: 112-1 Filed: 11/17/2017 Pg: 3 of 56 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS Amici curiae submit their corporate disclosure statements, as re- quired by Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 and 29(c), in Appendix B. -

Trump's Corporate Con

July 19, 2017 www.citizen.org Trump’s Corporate Con Job Six Months Into Term, Trump Has Fully Abandoned Populism In Favor of Giveaways to Industry Acknowledgments This report was written by, David Arkush, Rick Claypool, Taylor Lincoln, Bartlett Naylor, Tyson Slocum, Mike Tanglis and Alan Zibel, all of whom are researchers and policy experts with Public Citizen. It was edited by Zibel, Lincoln and Public Citizen President Robert Weissman. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national non-profit organization with more than 400,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government accountability. Public Citizen’s Congress Watch 215 Pennsylvania Ave. S.E Washington, D.C. 20003 P: 202-546-4996 F: 202-547-7392 http://www.citizen.org © 2017 Public Citizen. Public Citizen Corporate Con Job Contents AUTOS: BACKSLIDING ON FUEL ECONOMY ............................................................................................................ 7 Higher Fuel-Efficiency Standards on Hold ............................................................................................................. 7 Scuttling Fuel Economy Standards Would Cost Consumers Money and Harm the Environment......................... -

State of Hawaii V. Trump

Nos. 16-1436 & 16-1540 In the Supreme Court of the United States DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, et al., Petitioners, v. INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE ASSISTANCE PROJECT, et al., Respondents. DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES et al., Petitioners, v. STATE OF HAWAII, et al., Respondents. On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Courts of Appeals for the Fourth and Ninth Circuits BRIEF OF 161 TECHNOLOGY COMPANIES AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ANDREW J. PINCUS Counsel of Record PAUL W. HUGHES JOHN T. LEWIS Mayer Brown LLP 1999 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 (202) 263-3000 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Authorities.................................................... ii Interest of the Amici Curiae .......................................1 Introduction and Summary of Argument...................2 Argument.....................................................................6 I. Immigration Drives American Innovation And Economic Growth. ..........................................6 II. The Order Harms The Competitiveness Of American Companies...........................................11 III.The Order Is Unlawful.........................................16 A. Section 1182 does not empower the President to engage in wholesale, unilateral revision of the Nation’s immigration laws............................................16 1. The Order does not contain a finding sufficient to justify exercise of the President’s authority under Section 1182(f). .......................................................17 -

The Koch Government

THE KOCH GOVERNMENT HOW THE KOCH BROTHERS’ AGENDA HAS INFILTRATED THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION November 30, 2017 Acknowledgments This report was written Alan Zibel, Research Director for Public Citizen’s Corporate Presidency Project, with contributions from Mary Bottari of the Center for Media and Democracy, Scott Peterson of the Checks and Balances Project, Rick Claypool, research director for Public Citizen’s president’s office and Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen’s energy program. It was edited by Claypool and Public Citizen President Robert Weissman. Photo illustration by Zach Stone using caricatures by DonkeyHotey. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national non-profit organization with more than 400,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government accountability. www.citizen.org 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 P: 202-588-1000 http://www.citizen.org © 2017 Public Citizen. Public Citizen The Koch Government November 30, 2017 3 Public Citizen The Koch Government EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Donald Trump and the Koch brothers had a rocky relationship during the 2016 presidential campaign, despite the Kochs’ status as Republican mega-donors and kingmakers. Now, as the one- year anniversary of Trump’s inauguration approaches, political operatives and policy experts who have worked at numerous Koch-funded organizations have fanned out through the Trump Administration, taking jobs influencing education, energy, the environment, health care and taxes — all in service of a hard-right anti-government agenda.