This Is Smart Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Title: Suburban Verticalisation in London: Regeneration, Intra-Urban

Title: Suburban Verticalisation in London: regeneration, intra-urban inequality and social harm Abstract: With the rapid and large scaled expansion of new developments of high rise flats, London’s outer boroughs are seeing a suburban growth not seen since the 1930s. The objective of this mass verticalization are similar to the suburbanisation that occurred in the inter-war period in aiming to provide housing to a growing urban population. However behind the demographic imperative, other economic, socio-cultural and political processes come into play as they did in the past. Considering spatial, social and material transformations, the paper is concerned with a combination of factors, actors, structures and processes in this initial analysis of the new vertical suburbs of London. With this combined perspective, the analysis contributes to critical debates in criminology that are expanding to issues of social harm and social exclusion in the capitalist city. In this paper, I interrogate the fact that an increase of the housing stock only partially addresses the housing crisis in London as the problem of the provision of social housing is becoming increasingly limited under tight budget constraints and a financial structure that relies on and facilitates the involvement of the private sector in the delivery and management of housing. I also question the promises of regeneration solutions through new-build gentrification which have proved ineffective in other urban contexts and should be examined further in the context of London suburbs where the scale of construction is unprecedented and comes to exacerbate inequalities that have long been overlooked when the focus has been on inner boroughs and their gentrification. -

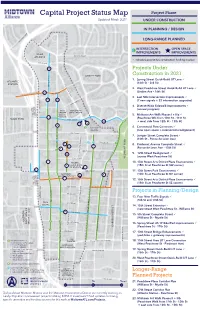

Capital Project Status Map Project Phase Updated March 2021 UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Capital Project Status Map Project Phase Updated March 2021 UNDER CONSTRUCTION IN PLANNING / DESIGN LONG-RANGE PLANNED Deering Road INTERSECTION OPEN SPACE IMPROVEMENTS IMPROVEMENTS SCAD Beverly Road ATLANTA indicates project has construction funding in place 19th Street 16 Projects Under ANSLEY PARK Construction in 2021 1. Spring Street Quick-Build LIT Lane ATLANTIC (16th St - 3rd St) STATION Peachtree Street Spring Street 2. West Peachtree Street Quick-Build LIT Lane (Linden Ave - 16th St) 22 17th Street 3. Last Mile Intersection Improvements 19 20 (7 new signals + 23 intersection upgrades) 16th Street 4. District-Wide Sidewalk Improvements ARTS WOODRUFF (annual program) Williams Street CENTER ARTS CENTER MARTA 5. Midtown Art Walk Phases I + IIIa 14 STATION HOME PARK (Peachtree Wlk from 10th St - 11th St 15th Street 3 18 + west side from 12th St - 13th St) 10 12 2 3 COLONY 6. Commercial Row Commons SQUARE (new open space + intersection realignment) 14th Street 7. Juniper Street Complete Street (14th St - Ponce de Leon Ave) 13 13 13 13th Street 3 5 8. Piedmont Avenue Complete Street West Peachtree Street Peachtree West 23 7 9 (Ponce de Leon Ave - 15th St) 12th Street Crescent Avenue 23 9. 12th Street Realignment (across West Peachtree St) 11th Street PIEDMONT PARK 1 FEDERAL 10. 15th Street Arts District Plaza Enancements 5 RESERVE BANK (15th St at Peachtree St SW corner) OF ATLANTA 11 17 10th Street 11. 10th Street Park Enancements MIDTOWN 8 (10th St at Peachtree St NE corner) MARTA STATION 6 3 21 Peachtree Place 12. 15th Street Arts District Plaza Enancements (15th St at Peachtree St SE corner) 8th Street Projects in Planning/Design 7th Street Williams Street 13. -

1 Can Public Procurement Aid The

Can public procurement aid the implementation of smart specialization strategies? Jon Mikel Zabala-Iturriagagoitiaa*, Edurne Magrob, Elvira Uyarrac, Kieron Flanaganc a.- Deusto Business School, University of Deusto, Donostia-San Sebastian (Spain) b.- Orkestra-Basque Institute of Competitiveness, University of Deusto, Donostia-San Sebastian (Spain) c.- Manchester Institute of Innovation Research, Alliance Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, Manchester (United Kingdom) * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract In recent decades sub-national regions have become ever more important as spaces for policy making. The current focus on research and innovation for smart specialisation strategies is the latest manifestation of this trend. By putting PPI processes at the core of regional and local development initiatives to support innovation, governments can go beyond priority setting to become active stakeholders engaged in entrepreneurial discovery processes. In this paper we offer a new conceptualization of how such smart specialisation strategies, as an example of a sub- national innovation policy, can help articulate demand for innovation. The paper presents an evolutionary framework that relates regional specialisation processes with the scale and scope of the demand associated to that specialisation. We identify four different roles for governments to be played, depending on the availability of local capabilities and the scale of the chosen priorities: government as a lead user, government as an innovation catalyst, -

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF of RETAIL AVAILABLE

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF OF RETAIL AVAILABLE LOCATED IN THE HEART OF 12TH AND MIDTOWN A premier apartment high rise building with a WELL POSITIONED RETAIL OPPORTUNITY Surrounded by Atlanta’s Highly affluent market, with Restaurant and retail vibrant commercial area median annual household opportunities available incomes over $74,801, and median net worth 330 Luxury apartment 596,000 SF Building $58 Million Project units. 476 parking spaces SITE PLAN - PHASE 4A / SUITE 3 / 1,861 SF* SITE PLAN 12th S TREET SUITERETAIL 1 RETAIL SUITERETAIL 3 RESIDENTIAL RETAIL RETAIL 1 2 3 LOBBY 4 5 2,423 SF 1,8611,861 SFSF SUITERETAIL 6A 3,6146 A SF Do Not Distrub Tenant E VENU RETAIL A 6 B SERVICE LOADING S C E N T DOCK SUITERETAIL 7 E 3,622 7 SF RETAIL PARKING CR COMPONENT N S I T E P L AN O F T H E RET AIL COMP ONENT ( P H ASE 4 A @ 77 12T H S TREE T ) COME JOIN THE AREA’S 1 2 TGREATH & MID OPERATORS:T O W N C 2013 THIS DRAWING IS THE PROPERTY OF RULE JOY TRAMMELL + RUBIO, LLC. ARCHITECTURE + INTERIOR DESIGN AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT WRITTEN CONSENT A TLANT A, GEOR G I A COMMISSI O N N O . 08-028.01 M A Y 28, 2 0 1 3 L:\06-040.01 12th & Midtown Master Plan\PRESENTATION\2011-03-08 Leasing Master Plan *All square footages are approximate until verified. THE MIDTOWN MARKET OVERVIEW A Mecca for INSPIRING THE CREATIVE CLASS and a Nexus for TECHNOLOGY + INNOVATION MORE THAN ONLY 3 BLOCKS AWAY FROM 3,000 EVENTS ANNUALLY PIEDMONT PARK • Atlanta Dogwood Festival, • Festival Peachtree Latino THAT BRING IN an arts and crafts fair • Music Midtown & • The finish line of the Peachtree Music Festival Peachtree Road Race • Atlanta Pride Festival & 6.5M VISITORS • Atlanta Arts Festival Out on Film 8 OF 10 ATLANTA’S “HEART OF THE ARTS”DISTRICT ATLANTA’S LARGEST LAW FIRMS • High Museum • ASO • Woodruff Arts Center • Atlanta Ballet 74% • MODA • Alliance Theater HOLD A BACHELORS DEGREE • SCAD Theater • Botanical Gardens SURROUNDED BY ATLANTA’S TOP EMPLOYERS R. -

Commercial Real Estate

COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE URBAN LAND INSTITUTE October 5-11, 2012 SPECIAL SECTION Page 25A Tapping resouces TAP teams wrestle development challenges By Martin Sinderman CONTRIBUTING WRITER roups dealing these communities come up with there are some projects done on a recommendations regarding development with real estate timely solutions.” pro bono basis. packages that identify the sites, program, development-related Potential TAP clients set things in motion The past year was a busy one for the expected goals, financing/ funding mecha- problems can tap by contacting the ULI Atlanta office. Once TAP program, Callahan reported, with a nisms, and other incentives to attract into an increasingly they are cleared for TAP treatment, they total of six TAPs undertaken. developers. popular source of receive the services of a ULI panel of These included one TAP where the The LCI study in Morrow dealt with assistance from subject-matter experts in fields such as Fulton Industrial Boulevard Community ideas regarding redevelopment of proper- the Urban Land development, urban design, city planning, Improvement District (CID) worked with ties that had been vacated by retailers over Institute. and/or other disciplines that deal with ULI Atlanta to obtain advice and the years, according to city of Morrow ULI’s Technical Assistance Program, commercial retail, office, industrial, recommendations on the revitalization Planning & Economic Development G or TAP, provides what it describes as residential and mixed land uses. and improved economic competitiveness -

Transit Planning Practice in the Age of Transit-Oriented Development by Ian Robinson Carlton a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Transit Planning Practice in the Age of Transit-Oriented Development By Ian Robinson Carlton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in City & Regional Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Chatman, Chair Professor Robert Cervero Professor Dwight Jaffee Fall 2013 © Copyright by Ian Robinson Carlton 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract Transit Planning Practice in the Age of Transit-Oriented Development by Ian Robinson Carlton Doctor of Philosophy in City & Regional Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Chatman, Chair Globally, urban development near transit stations has long been understood to be critical to transit’s success primarily because it can contribute to ridership and improve the efficiency of transit investments. In the United States in particular, fixed-guideway transit’s land use-shaping capability has been an important justification and goal for transit investment. In fact, today’s U.S. federal funding policies increasingly focus on achieving transit-oriented real estate development near new transit infrastructure. However, the widespread implementation of transit and land use coordination practices has been considered an uphill battle. The academic literature suggests the most effective practice may be for U.S. transit planners to locate transit stations where pre-existing conditions are advantageous for real estate development or transit investments can generate the political will to dramatically alter local conditions to make them amenable to real estate development. However, prior to this study, no research had investigated the influence of real estate development considerations on U.S. -

Why Smart Growth: a Primer

WHY SMART GROWTH: A PRIMER International City/County Management Association with Geoff Anderson ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to acknowledge the efforts of Geoffrey Anderson of the U.S. Environ mental Protection Agency (EPA). Without his assistance this primer would not exist. In addition, Mike Siegel, Gary Lawrence, Don Chen, Reid Ewing, Paul Alsenas, reviewers at the National Association of Counties and the International City/County Management Association (ICMA), and many others provided invaluable suggestions and expertise. A final thank you to Kendra Briechle for helping to pull it all together. About the Smart Growth Network The Smart Growth Network is a coalition of private sector, public sector, and non- governmental partner organizations seeking to create smart growth in neighborhoods, communities, and regions across the United States. Network Partners include the U.S. EPA's Urban and Economic Development Division, ICMA, Center for Neighborhood Technology, Congress for the New Urbanism, Joint Center for Sustainable Communi ties, Natural Resources Defense Council, The Northeast-Midwest Institute, State of Maryland, Surface Transportation Policy Project, Sustainable Communities Network, and Urban Land Institute. About the International City/County Management Association ICMA is the professional and educational association for appointed administrators and assistant administrators serving cities, towns, villages, boroughs, townships, coun ties, and regional councils. ICMA serves as the organizational home of the Smart Growth Network and runs the Network’s membership program. ICMA helps local governments create sustainable communities through smart growth activities and related programs. For more information on the Smart Growth Network, contact ICMA or visit the Smart Growth Website at http://www.smartgrowth.org. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Smart Growth and Economic Success: Benefits for Real Estate Developers, Investors, Businesses, and Local Governments

United States December 2012 Environmental Protection Agency www.epa.gov/smartgrowth SMART GROWTH AND ECONOMIC SUCCESS: BENEFITS FOR REAL ESTATE DEVELOPERS, INVESTORS, BUSINESSES, AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS Office of Sustainable Communities Smart Growth Program (Distributed at 1/14/13 Sustainable Thurston Task Force meeting) Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the EPA’s Office of Sustainable Communities with the assistance of Renaissance Planning Group under contract number EP-W-11-009/010/11. Principal Staff Contacts: Melissa Kramer and Lee Sobel Mention of trade names, products, or services does not convey official EPA approval, endorsement, or recommendation. Cover photos (left to right, top to bottom): Barracks Row in Washington, D.C., courtesy of Lee Sobel; TRAX light rail in Sandy, Utah, courtesy of Melissa Kramer; Mission Creek Senior Community in San Francisco, California, courtesy of Alan Karchmer and Mercy Housing Inc. (Distributed at 1/14/13 Sustainable Thurston Task Force meeting) Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ i I. Economic Advantages of Smart Growth Strategies .............................................................................. 1 II. Economic Advantages of Compact Development ................................................................................. 4 A. Higher Revenue Generation per Acre of Land ................................................................................. -

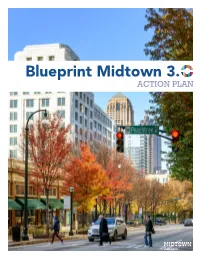

Blueprint Midtown 3. ACTION PLAN Introduction

Blueprint Midtown 3. ACTION PLAN Introduction This document identifies Midtown’s goals, implementation strategies and specific action items that will ensure a rich diversity of land uses, vibrant street-level activity, quality building design, multimodal transportation accessibility and mobility, and engaging public spaces. Blueprint Midtown 3.0 is the most recent evolution of Midtown Alliance’s community driven plan that builds on Midtown’s fundamental strengths and makes strategic improvements to move the District from great to exceptional. It identifies both high priority projects that will be advanced in the next 10 years, as well as longer-term projects and initiatives that may take decades to achieve but require exploration now. Since 1997, policies laid out in Blueprint Midtown have guided public and private investment to create a clean, safe, and vibrant urban environment. The original plan established a community vision for Midtown that largely remains the same: a livable, walkable district in the heart of Atlanta; a place where people, business and culture converge to create a live-work-play community with a distinctive personality and a premium quality of life. Blueprint Midtown 3.0 builds on recent successes, incorporates previously completed studies and corridor plans, draws inspiration from other places and refines site-specific recommendations to reflect the changes that have occurred in the community since the original unveiling of Blueprint Midtown. Extensive community input conducted in 2016 involving more than 6,000 Midtown employers, property owners, residents, workers, visitors, public-sector partners, and subject-matter experts validates the Blueprint Midtown vision for an authentic urban experience. The Action Plan lives with a family of Blueprint Midtown 3.0 documents which also includes: Overview: Moving Forward with Blueprint Midtown 3.0, Midtown Character Areas Concept Plans (coming soon), Appendices: Project Plans and 5-Year Work Plan (coming soon). -

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism 1 Cover photo: Lancaster Boulevard in Lancaster, California. Source: City of Lancaster. Photo by Tamara Leigh Photography. Street design by Moule & Polyzoides. 25 GREAT IDEAS OF NEW URBANISM Author: Robert Steuteville, CNU Senior Dyer, Victor Dover, Hank Dittmar, Brian Communications Advisor and Public Square Falk, Tom Low, Paul Crabtree, Dan Burden, editor Wesley Marshall, Dhiru Thadani, Howard Blackson, Elizabeth Moule, Emily Talen, CNU staff contributors: Benjamin Crowther, Andres Duany, Sandy Sorlien, Norman Program Fellow; Mallory Baches, Program Garrick, Marcy McInelly, Shelley Poticha, Coordinator; Moira Albanese, Program Christopher Coes, Jennifer Hurley, Bill Assistant; Luke Miller, Project Assistant; Lisa Lennertz, Susan Henderson, David Dixon, Schamess, Communications Manager Doug Farr, Jessica Millman, Daniel Solomon, Murphy Antoine, Peter Park, Patrick Kennedy The 25 great idea interviews were published as articles on Public Square: A CNU The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) Journal, and edited for this book. See www. helps create vibrant and walkable cities, towns, cnu.org/publicsquare/category/great-ideas and neighborhoods where people have diverse choices for how they live, work, shop, and get Interviewees: Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Jeff around. People want to live in well-designed Speck, Dan Parolek, Karen Parolek, Paddy places that are unique and authentic. CNU’s Steinschneider, Donald Shoup, Jeffrey Tumlin, mission is to help build those places. John Anderson, Eric Kronberg, Marianne Cusato, Bruce Tolar, Charles Marohn, Joe Public Square: A CNU Journal is a Minicozzi, Mike Lydon, Tony Garcia, Seth publication dedicated to illuminating and Harry, Robert Gibbs, Ellen Dunham-Jones, cultivating best practices in urbanism in the Galina Tachieva, Stefanos Polyzoides, John US and beyond. -

Smart Growth Guide

LOCAL GOVERNMENT CLIMATE AND ENERGY STRATEGY SERIES Smart Growth A Guide to Developing and Implementing Greenhouse Gas Reductions Programs Community Planning and Design U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY 2011 EPA’s Local Government Climate and Energy Strategy Series The Local Government Climate and Energy Strategy Series provides a comprehensive, straightforward overview of green- house gas (GHG) emissions reduction strategies for local governments. Topics include energy efficiency, transportation, community planning and design, solid waste and materials management, and renewable energy. City, county, territorial, tribal, and regional government staff, and elected officials can use these guides to plan, implement, and evaluate their climate change mitigation and energy projects. Each guide provides an overview of project benefits, policy mechanisms, investments, key stakeholders, and other imple- mentation considerations. Examples and case studies highlighting achievable results from programs implemented in communities across the United States are incorporated throughout the guides. While each guide stands on its own, the entire series contains many interrelated strategies that can be combined to create comprehensive, cost-effective programs that generate multiple benefits. For example, efforts to improve energy efficiency can be combined with transportation and community planning programs to reduce GHG emissions, decrease energy and transportation costs, improve air quality and public health, and enhance quality of life. LOCAL GOVERNMENT