Critical Issues in Justice and Politics ISSN 1940-3186

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

History of Quezon City Public Library

HISTORY OF QUEZON CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY The Quezon City Public Library started as a small unit, a joint venture of the National Library and Quezon City government during the incumbency of the late Mayor Ponciano Bernardo and the first City Superintendent of Libraries, Atty. Felicidad Peralta by virtue of Public Law No. 1935 which provided for the “consolidation of all libraries belonging to any branch of the Philippine Government for the creation of the Philippine Library”, and for the maintenance of the same. Mayor Ponciano Bernardo 1946-1949 June 19, 1949, Republic Act No. 411 otherwise known as the Municipal Libraries Law, authored by then Senator Geronimo T. Pecson, which is an act to “provide for the establishment, operation and Maintenance of Municipal Libraries throughout the Philippines” was approved. Mrs. Felicidad A. Peralta 1948-1978 First City Librarian Side by side with the physical and economic development of Quezon City officials particularly the late Mayor Bernardo envisioned the needs of the people. Realizing that the achievements of the goals of a democratic society depends greatly on enlightened and educated citizenry, the Quezon City Public Library, was formally organized and was inaugurated on August 16, 1948, with Aurora Quezon, as a guest of Honor and who cut the ceremonial ribbon. The Library started with 4, 000 volumes of books donated by the National Library, with only four employees to serve the public. The library was housed next to the Post Office in a one-storey building near of the old City Hall in Edsa. Even at the start, this unit depended on the civic spirited members of the community who donated books, bookshelves and other reading material. -

Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No

The Politics of Naming a Movement: Independent Cinema According to the Cinemalaya Congress (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, December 2011, pp. 76- 110 ISSN 0031-7802 © 2011 University of the Philippines 76 THE POLITICS OF NAMING A MOVEMENT: INDEPENDENT CINEMA ACCORDING TO THE CINEMALAYA CONGRESS (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Much has been said and written about contemporary “indie” cinema in the Philippines. But what/who is “indie”? The catchphrase has been so frequently used to mean many and sometimes disparate ideas that it has become a confusing and, arguably, useless term. The paper attempts to problematize how the term “indie” has been used and defined by critics and commentators in the context of the Cinemalaya Film Congress, which is one of the important venues for articulating and evaluating the notion of “independence” in Philippine cinema. The congress is one of the components of the Cinemalaya Independent Film Festival, whose founding coincides with and is partly responsible for the increase in production of full-length digital films since 2005. This paper examines the politics of naming the contemporary indie movement which I will discuss based on the transcripts of the congress proceedings and my firsthand experience as a rapporteur (2007- 2009) and panelist (2010) in the congress. Panel reports and final recommendations from 2005 to 2010 will be assessed vis-a-vis the indie films selected for the Cinemalaya competition and exhibition during the same period and the different critical frameworks which panelists have espoused and written about outside the congress proper. Ultimately, by following a number PHILIPPINE HUMANITIES REVIEW 77 of key and recurring ideas, the paper looks at the key conceptions of independent cinema proffered by panelists and participants. -

MDG Report 2010 WINNING the NUMBERS, LOSING the WAR the Other MDG Report 2010

Winning the Numbers, Losing the War: The Other MDG Report 2010 WINNING THE NUMBERS, LOSING THE WAR The Other MDG Report 2010 Copyright © 2010 SOCIAL WATCH PHILIPPINES and UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (UNDP) All rights reserved Social Watch Philippines and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) encourage the use, translation, adaptation and copying of this material for non-commercial use, with appropriate credit given to Social Watch and UNDP. Inquiries should be addressed to: Social Watch Philippines Room 140, Alumni Center, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1101 Telefax: +63 02 4366054 Email address: [email protected] Website: http://www.socialwatchphilippines.org The views expressed in this book are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily refl ect the views and policies of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Editorial Board: LEONOR MAGTOLIS BRIONES ISAGANI SERRANO JESSICA CANTOS MARIVIC RAQUIZA RENE RAYA Editorial Team: Editor : ISAGANI SERRANO Copy Editor : SHARON TAYLOR Coordinator : JANET CARANDANG Editorial Assistant : ROJA SALVADOR RESSURECCION BENOZA ERICSON MALONZO Book Design: Cover Design : LEONARD REYES Layout : NANIE GONZALES Photos contributed by: Isagani Serrano, Global Call To Action Against Poverty – Philippines, Medical Action Group, Kaakbay, Alain Pascua, Joe Galvez, Micheal John David, May-I Fabros ACKNOWLEDGEMENT any deserve our thanks for the production of this shadow report. Indeed there are so many of them that Mour attempt to make a list runs the risk of missing names. Social Watch Philippines is particularly grateful to the United Nations Millennium Campaign (UNMC), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund (MDG-F) and the HD2010 Platform for supporting this project with useful advice and funding. -

Free the the Department of Justice Has Already Submitted Its Health Workers Is Another Day Recommendations Regarding the Case of the 43 Health Workers

Another day in prison for the and their families tormented. FREE THE The Department of Justice has already submitted its health workers is another day recommendations regarding the case of the 43 health workers. The President himself has admitted that the that justice is denied. search warrant was defective and the alleged evidence President Benigno Aquino III should act now against the Morong 43 are the “fruit of the poisonous for the release of the Morong 43. tree.” Various local and international organizations Nine months ago in February, the 43 health workers have called for the health workers’ release. including 26 women – two of whom have already given When Malacañang granted amnesty to rebel birth while in prison – were illegally arrested, searched, soldiers, many asked why the Morong 43 remained 43! detained, and tortured. Their rights are still being violated in prison. We call on the Aquino government to withdraw the charges against the Morong 43 and release them unconditionally! Most Rev. Antonio Ledesma, Archbishop, Metropolitan Archdiocese of CDO • Atty. Roan Libarios, IBP • UN Ad Litem Judge Romeo Capulong • Former SolGen Atty. Frank Chavez • Farnoosh Hashemian, MPH, Nat’l Lawyers Guild • Rev. Nestor Gerente, UMC, CA • Danny Bernabe, Echo Atty. Socorro Eemac Cabreros, IBP Davao City Pres. (2009) • Atty. Federico Gapuz, UPLM • Atty. Beverly Park UMC • J. Luis Buktaw, UMC LA, CA • Sr. Corazon Demetillo, RGS • Maria Elizabeth Embry, Antioch Most Rev. Oscar Cruz, Archbishop Emeritus, Archdiocese of Lingayen • Most Selim-Musni • Atty. Edre Olalia, NUPL • Atty. Joven Laura, Atty. Julius Matibag, NUPL • Atty. Ephraim CA • Haniel Garibay, Nat’l Assoc. -

Duterte and Philippine Populism

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ASIA, 2017 VOL. 47, NO. 1, 142–153 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751 COMMENTARY Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism Nicole Curato Centre for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance, University of Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This commentary aims to take stock of the 2016 presidential Published online elections in the Philippines that led to the landslide victory of 18 October 2016 ’ the controversial Rodrigo Duterte. It argues that part of Duterte s KEYWORDS ff electoral success is hinged on his e ective deployment of the Populism; Philippines; populist style. Although populism is not new to the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte; elections; Duterte exhibits features of contemporary populism that are befit- democracy ting of an age of communicative abundance. This commentary contrasts Duterte’s political style with other presidential conten- ders, characterises his relationship with the electorate and con- cludes by mapping populism’s democratic and anti-democratic tendencies, which may define the quality of democratic practice in the Philippines in the next six years. The first six months of 2016 were critical moments for Philippine democracy. In February, the nation commemorated the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution – a series of peaceful mass demonstrations that ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III – the son of the president who replaced the dictator – led the commemoration. He asked Filipinos to remember the atrocities of the authoritarian regime and the gains of democracy restored by his mother. He reminded the country of the torture, murder and disappearance of scores of activists whose families still await compensation from the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board. -

A Dirty Affair Political Melodramas of Democratization

6 A Dirty Affair Political Melodramas of Democratization Ferdinand Marcos was ousted from the presidency and exiled to Hawaii in late February 1986,Confidential during a four-day Property event of Universitycalled the “peopleof California power” Press revolution. The event was not, as the name might suggest, an armed uprising. It was, instead, a peaceful assembly of thousands of civilians who sought to protect the leaders of an aborted military coup from reprisal by***** the autocratic state. Many of those who gathered also sought to pressure Marcos into stepping down for stealing the presi- dential election held in December,Not for Reproduction not to mention or Distribution other atrocities he had commit- ted in the previous two decades. Lino Brocka had every reason to be optimistic about the country’s future after the dictatorship. The filmmaker campaigned for the newly installed leader, Cora- zon “Cory” Aquino, the widow of slain opposition leader Ninoy Aquino. Despite Brocka’s reluctance to serve in government, President Aquino appointed him to the commission tasked with drafting a new constitution. Unfortunately, the expe- rience left him disillusioned with realpolitik and the new government. He later recounted that his fellow delegates “really diluted” the policies relating to agrarian reform. He also spoke bitterly of colleagues “connected with multinationals” who backed provisions inimical to what he called “economic democracy.”1 Brocka quit the commission within four months. His most significant achievement was intro- ducing the phrase “freedom of expression” into the constitution’s bill of rights and thereby extending free speech protections to the arts. Three years after the revolution and halfway into Mrs. -

Proceeding 2018

PROCEEDING 2018 CO OCTOBER 13, 2018 SAT 8:00AM – 5:30PM QUEZON CITY EXPERIENCE, QUEZON MEMORIAL, Q.C. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EDITOR Ernie M. Lopez, MBA Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa, AA MANAGING EDITOR EDITORIAL BOARD Jose F. Peralta, DBA, CPA PRESIDENT, CHIEF ACADEMIC OFFICER & DEAN Antonio M. Magtalas, MBA, CPA VICE PRESIDENT FOR FINANCE & TREASURER Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. ASSOCIATE DEAN Jose Teodorico V. Molina, LLM, DCI, CPA CHAIR, GSB AD HOC COMMITTEE EDITORIAL STAFF Ernie M. Lopez Susan S. Cruz Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa Philip Angelo Pandan The PSBA THIRD INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH COLLOQUIUM PROCEEDINGS is an official business publication of the Graduate School of Business of the Philippine School of Business Administration – Manila. It is intended to keep the graduate students well-informed about the latest concepts and trends in business, management and general information with the goal of attaining relevance and academic excellence. PSBA Manila 3IRC Proceedings Volume III October 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description Page Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. i Concept Note ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Program of Activities .......................................................................................................................... 6 Resource -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

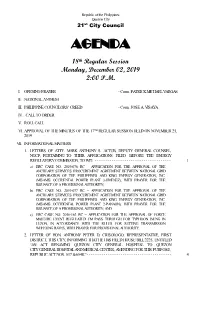

AGENDA (18Th Regular Session)

Republic of the Philippines Quezon City 21st City Council AGENDA 18th Regular Session Monday, December 02, 2019 2:00 P.M. I. OPENING PRAYER - Coun. PATRICK MICHAEL VARGAS II. NATIONAL ANTHEM III. PHILIPPINE COUNCILORS’ CREED - Coun. JOSE A. VISAYA IV. CALL TO ORDER V. ROLL CALL VI. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES OF THE 17TH REGULAR SESSION HELD ON NOVEMBER 25, 2019. VII. INFORMATIONAL MATTERS 1. LETTERS OF ATTY. MARK ANTHONY S. ACTUB, DEPUTY GENERAL COUNSEL, NGCP, PERTAINING TO THEIR APPLICATIONS FILED BEFORE THE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION, TO WIT: - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 a) ERC CASE NO. 2019-076 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF THE ANCILLARY SERVICES PROCUREMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN NATIONAL GRID CORPORATION OF THE PHILIPPINES AND KING ENERGY GENERATION, INC. (MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL POWER PLANT 3-JIMENEZ), WITH PRAYER FOR THE ISSUANCE OF A PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY; b) ERC CASE NO. 2019-077 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF THE ANCILLARY SERVICES PROCUREMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN NATIONAL GRID CORPORATION OF THE PHILIPPINES AND KING ENERGY GENERATION, INC. (MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL POWER PLANT 2-PANAON), WITH PRAYER FOR THE ISSUANCE OF A PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY; AND c) ERC CASE NO. 2016-163 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF FORCE MAJEURE EVENT REGULATED FM PASS THROUGH FOR TYPHOON INENG IN LUZON, IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE RULES FOR SETTING TRANSMISSION WHEELING RATES, WITH PRAYER FOR PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY. 2. LETTER OF HON. ANTHONY PETER D. CRISOLOGO, REPRESENTATIVE, FIRST DISTRICT, THIS CITY, INFORMING THAT HE HAS FILED HOUSE BILL 2225, ENTITLED “AN ACT RENAMING QUEZON CITY GENERAL HOSPITAL TO QUEZON CITY GENERAL HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL CENTER, AMENDING FOR THIS PURPOSE, REPUBLIC ACT NOS. -

NOSI BALASI? MNLF Lay Siege on Zamboanga City

September 2013 1 JOIN OUR GROWING NUMBER OF INTERNET READERS RECEIVE A FREE MONTHLY ONLINE SEPTEMBER 2013 COPY. Vol. 2 No.9 EMAIL US AT: wavesnews247 @gmail.com Double Trouble PNoy faces two big crisis: Pork Barrel “Scam-dal” MNLF Zambo attack NOSI BALASI? MNLF Lay Siege on Zamboanga City By wavesnews staff with files from Philippine Daily Inquirer By wavesnews staff with files from Philippine Daily Inquirer NOSI BALASI ? SINO BA SILA ? Who are the senators, congressmen, govern- ment officials and other individuals involved in the yet biggest corruption case ever to hit the Philippine government to the tune of billions and bil- lions of pesos as probers continue to unearth more anomalies on the pork barrel or Priority Development Assistance fund (PDAF)? Sept.16, Monday, the department of Justice formally filed plunder charges against senators Ramon “Bong Revilla jr., Jinggoy Estrada and Juan Ponce Combat police forces check their comrade (C) who was hit by Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) sniper fire in downtown Zamboanga City. Photo: AFP CHARGED! Muslim rebels under the Moro Na- standstill, classes suspended and tional Liberation Front (MNLF) of curfew enforced from 8:00pm to Nur Misuari “invaded” Zamboanga 5:00am to protect residents being city Sept.8 at dawn taking over sev- caught in the hostilities. eral barangays (villages), held hun- dreds of residents hostages and Already there are some 82,000 dis- (from left) Senate Minority Leader Juan Ponce-Enrile, and Senators Jose “Jinggoy” Es- placed residents of the city while at trada and Ramon “Bong” Revilla Jr. INQUIRER FILE PHOTOS engaged government soldiers in running gun battles that has so far least four barangays remained un- Enrile along with alleged mastermind Janet Lim Napoles and 37 others. -

Sharpening the Sword of State Building Executive Capacities in the Public Services of the Asia-Pacific

SHARPENING THE SWORD OF STATE BUILDING EXECUTIVE CAPACITIES IN THE PUBLIC SERVICES OF THE ASIA-PACIFIC SHARPENING THE SWORD OF STATE BUILDING EXECUTIVE CAPACITIES IN THE PUBLIC SERVICES OF THE ASIA-PACIFIC Edited by Andrew Podger and John Wanna Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Sharpening the sword of state : building executive capacities in the public services of the Asia-Pacific / editors: Andrew Podger, John Wanna. ISBN: 9781760460723 (paperback) 9781760460730 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series. Subjects: Public officers--Training of--Pacific Area. Civil service--Pacific Area--Personnel management. Public administration--Pacific Area. Pacific Area--Officials and employees. Pacific Area--Politics and government. Other Creators/Contributors: Podger, A. S. (Andrew Stuart), editor. Wanna, John, editor. Dewey Number: 352.669 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph adapted from: ‘staples’ by jar [], flic.kr/p/97PjUh. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents Figures . vii Tables . ix Abbreviations . xi Contributors . xvii 1 . Public sector executive development in the Asia‑Pacific: Different contexts but similar challenges . 1 Andrew Podger 2 . Developing leadership and building executive capacity in the Australian public services for better governance . 19 Peter Allen and John Wanna 3 . Civil service executive development in China: An overview .