Kelucharan Mohapatra and the Making <If Odissi Dance*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

List of Artistes Performed Under the “Monthly Baithak” and “Special Programme” Series of Pracheen Kala Kendra, Chandigarh Since 1996

List of artistes performed under the “Monthly Baithak” and “Special Programme” series of Pracheen Kala Kendra, Chandigarh since 1996. Baithak/Spl. Program & Art Form Date of Name of Artist Performance 1st Baithak Sitar Recital 1.6.1996 Ustad Shahid Parvez Kathak Dance Uma Dogra 2nd Baithak 3.8.1996 Students of the Kendra 3rd Baithak Vocal Recital 1.9.1996 Sarathi Chatterjee 4th Baithak Kathak Dance 1.9.1996 Bharati Gupta 5th Baithak Kathak Dance October 1996 Anuradha Arora 6th Baithak Vocal Recital 16.11.1996 Sumitra Guha 7th Baithak Sarod Recital 11.12.1996 Danish Aslam Khan 8th Baithak Odissi Dance 11.1.1997 Ranjana Guhar 9th Baithak Vocal Recital 11.2.1997 Subhagya Vardhan 10th Baithak Kathak Dance 11.3.1997 Geetanjali Lal 11th Baithak Odissi Dance 11.4.1997 Phalguni Sengupta 12th Baithak Violin Recital 11.5.1997 Ashghar Hussain 13th Baithak Vocal Recital 11.7.1997 Usha Parkhi 14th Baithak Vocal Recital 11.8.1997 Rattan Mohan Sharma 15th Baithak Sitar Recital 11.9.1997 Aparna Deodhar 16th Baithak Kathak Dance 11.10.1997 Anuradha Arora 17th Baithak Bhajan Sandhya 11.11.1997 Meera Gautam 18th Baithak Bharatnatyam 11.12.1997 Rani Shingal 19th Baithak Kathak Dance 11.1.1998 Anurekha Ghosh 20th Baithak Sitar Recital 11.2.1998 Manu Kumar Seen 21st Baithak Vocal Recital 11.3.1998 Mahendra Sharma 22nd Baithak Bharatnatyam 11.4.1998 A.R.Tejender 23rd Baithak Vocal Recital 11.5.1998 Suhasini Koratkar 24th Baithak Kathak Dance 11.6.1998 Gourie Verma 25th Baithak Kuchipudi Dance 11.7.1998 Meenu Thakur 26th Baithak Vocal Recital 11.8.1998 Shanti Sharma 27th Baithak Sitar Recital 11.9.1998 Harvinder Kr. -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

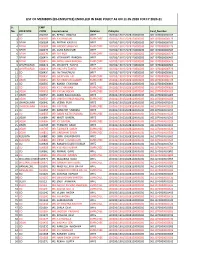

List of Members (Ex-Employee) Enrolled in Base Policy As on 11.05.2020 for Fy 2020-21

LIST OF MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEE) ENROLLED IN BASE POLICY AS ON 11.05.2020 FOR FY 2020-21 Sr. EMP No. LOCATION CODE Insured name Relation PolicyNo Card_Number 1 CO 00016G MS. REENA JHINGAN WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000103 2 CO 00016G MR. K K JHINGAN EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000126 3 DELHI 00030B MS. PRITPAL KAUR VIJ WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000203 4 DELHI 00030B MR. ANOOP SINGH VIJ EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000226 5 DELHI 00037K MS. ASHA RANI PURI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000303 6 DELHI 00037K MR. D D PURI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000326 7 DELHI 00041H MS. VIDYAWATI RANGRA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000403 8 DELHI 00041H MR. BIDHU RAM RANGRA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000426 9 AHMEDABAD 00042A MS. CHANDER TANEJA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000503 10 AHMEDABAD 00042A MR. VAS DEV TANEJA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000526 11 CO 00043D MS. LALTHANZAUVI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000603 12 CO 00043D MR. SAJEEVAN LAL EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000626 13 DELHI 00045L MR. SRI KRISHAN GANDHI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000726 14 CO 00050G MS. KANAK CHAUHAN WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000803 15 CO 00050G MR. K S CHAUHAN EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000826 16 DELHI 00051E MR. K K SACHDEVA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000926 17 DELHI 00055H MS. SAROJ BALA NAGPAL WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001003 18 DELHI 00055H MR. VINOD KUMAR NAGPAL EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001026 19 CHANDIGARH 00064G MS. VEENA PURI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001103 20 CHANDIGARH 00064G MR. V K PURI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001126 21 CO 00065E MS. KAMLESH SHARMA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001203 22 CO 00065E MR. BADRI NATH SHARMA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001226 23 DELHI 00069H MS. -

Palm Leaf Manuscripts Inheritance of Odisha: a Historical Survey

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2019; 5(4): 77-82 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2019; 5(4): 77-82 Palm leaf manuscripts inheritance of Odisha: A © 2019 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com historical survey Received: 16-05-2019 Accepted: 18-06-2019 Dr. Jharana Rani Tripathy Dr. Jharana Rani Tripathy PDF Scholar Dept.of Sanskrit Pondicherry University, Introduction Pondicherry, India Odisha was well-known as Kalinga, Kosala, Odra and Utkala during ancient days. Altogether these independent regions came under one administrative control which was known as Utkala and subsequently Orissa. The name of Utkala has been mentioned in Mahabharata, Ramayana and Puranas. The existence of Utkala as a kingdom is found in Kalidas's Raghuvamsa. It is stated that king Raghu after having crossed the river Kapisa reached the Utkala country and finally went to Kalinga. The earliest epigraphic evidence to Utakaladesa is found from the Midnapur plate of Somdatta which includes Dandabhukti within its jurisdiction1. The plates record that while Sasanka was ruling the earth, his feudatory Maharaja Somadatta was governing the province of Dandabhukti adjoining the Utkala-desa. The Kelga plate 8 indicate s that Udyotakesari's son and successors of Yayati ruled about the 3rd quarter of eleventh century, made over Kosala to prince named Abhimanyu and was himself ruling over Utkala After the down-fall of the Matharas in Kalinga, the Gangas held the reines of administration in or about 626-7 A, D. They ruled for a long period of about five hundred years, when, at last,they extended their power as far as the Gafiga by sujugating Utkala in or about 1112 A. -

Hectic Campaign Ends on a Bitter Note

follow us: friday, may 11, 2018 Delhi City Edition thehindu.com 36 pages ț ₹10.00 facebook.com/thehindu twitter.com/the_hindu Printed at . Chennai . Coimbatore . Bengaluru . Hyderabad . Madurai . Noida . Visakhapatnam . Thiruvananthapuram . Kochi . Vijayawada . Mangaluru . Tiruchirapalli . Kolkata . Hubballi . Mohali . Malappuram . Mumbai . Tirupati . lucknow . cuttack . patna NEARBY Hectic campaign Mahathir stages a surprise comeback Becomes the world’s oldest elected leader; sworn in as Malaysia’s Prime Minister Agence France-Presse won 121 seats, comfortably ends on a bitter note Reuters more than the 112 required to Kuala Lumpur rule. He said he had been as No decision yet on Raja Rajeshwari Nagar seat in Karnataka Ninetytwoyearold Mahath sured of support from a raft SC Collegium to ir Mohamad was on Thurs of parties that would give his meet today Special Correspondent day sworn in as the world’s government 135 members of NEW DELHI Bengaluru oldest elected leader after a parliament. The fivejudge Collegium led A month of highdecibel stunning election win that In a ceremony at the na by Chief Justice of India Dipak campaigning for the Karna swept Malaysia’s establish tional palace steeped in cen Misra is scheduled to meet on taka Assembly election — ment from power after more turiesold Muslim Malay tra Friday to decide on the which saw national and lo than six decades. dition, Mr. Mahathir was government’s objections to the elevation of Uttarakhand cal leaders participating in a In a huge upset, former sworn in as Prime Minister High Court Chief Justice K.M. series of political rallies strongman Mr. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Fashioning Readers: Canon, Criticism and Pedagogy in the Emergence of Modern Oriya Literature

1 Fashioning Readers: Canon, Criticism and Pedagogy in the Emergence of Modern Oriya Literature Pritipuspa Mishra University of Southampton Postal Address: University of Southampton Avenue Campus Highfield Southampton SO17 1BF UK Email- [email protected] This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Contemporary South Asia on 22nd March 2012, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2011.646080 Abstract Through a brief history of a widely published canon debate in nineteenth century Orissa, this paper describes how anxieties about the quality of “traditional” Oriya literature served as a site for imagining a cohesive Oriya public who would become the consumers and beneficiaries of a new, modernized Oriya-language canon. A public controversy about the status of Oriya literature was initiated in the 1890s with the publication of a serialized critique of the works of Upendra Bhanja, a very popular pre-colonial Oriya poet. The critic argued that Bhanja’s writing was not true poetry, that it did not speak to the contemporary era, and that it featured embarrassingly detailed discussions of obscene material. By unpacking the terms of this criticism and Oriya responses to it, I reveal how at the heart of these discussions were concerns about community building that presupposed a new kind of readership of literature in the Oriya language. Ultimately, this paper offers a longer, regional history to the emerging concern of post-colonial scholarship with relationships between publication histories, readerships, and broader ideas of community—local, Indian and global. Key words Literary Criticism, Oriya literature, Tradition, Public Word Count: 7344 including references 2 In the winter of 1891, in the capital of the princely state of Majurbhanj set deep in the hills of the Eastern Ghats, a series of articles critiquing the work of an early modern Oriya poet were published. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 8 MARCH - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Sri Krsna - Jagannath Consciousness : Vyasa - Jayadeva - Sarala Dasa Dr. Satyabrata Das ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty ... 4 Language and Language Policy in India Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Rise of the Odia Novel : 1897-1930 Jitendra Narayan Patnaik ... 18 Gangadhar Literature : A Bird’s Eye View Jagabandhu Panda ... 23 Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath ... 25 The Evolution of Odia Language : An Introspection Dr. Jyotirmati Samantaray ... 29 Biju - The Greatest Odia in Living Memory Rajkishore Mishra ... 31 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 34 Role of Maharaja Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo in the Odia Language Movement Harapriya Das Swain ... 38 Odissi Vocal : A Unique Classical School Kirtan Narayan Parhi .. -

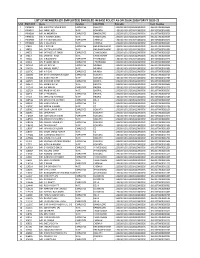

LIST of MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEES) ENROLLED in BASE POLICY AS on 20.04.2020 for FY 2020-21 S.NO EMPCODE Name Relation LOCATION Policyno Card Number 1 PRMB22 MR

LIST OF MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEES) ENROLLED IN BASE POLICY AS ON 20.04.2020 FOR FY 2020-21 S.NO EMPCODE Name Relation LOCATION PolicyNo Card_Number 1 PRMB22 MR. SWAPAN KUMAR ROY EMPLOYEE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283626 2 PRMB22 MS. DIPALI ROY WIFE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283603 3 PRMB19 MR. M AKBARSHA EMPLOYEE BANGALORE :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283526 4 PRMB19 MS. A HAMIDA BANU WIFE BANGALORE :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283503 5 PRMB09 MR. T S VIJAYAKUMAR EMPLOYEE CHENNAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283426 6 PRMB09 MS. V KALAIVANI WIFE CHENNAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283403 7 14819J MR. P N PATRI EMPLOYEE BHUBANESHWAR :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283326 8 14819J MS. GEETANJALI PATRI WIFE BHUBANESHWAR :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283303 9 14027J MR. JATINDERJIT SINGH EMPLOYEE CHANDIGARH :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283226 10 14027J MS. JASWANT KAUR WIFE CHANDIGARH :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283203 11 13346J MS. D RAMADEVI EMPLOYEE HYDERABAD :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283126 12 13314L MS. P SABIRUNNISA EMPLOYEE HYDERABAD :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283026 13 12435D MR. H C RAJPUT EMPLOYEE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282926 14 12435D MS. MANJU RAJPUT WIFE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282903 15 12363C MR. N R DAS EMPLOYEE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282826 16 12358G MR. BHIM CHANDRA HALDER EMPLOYEE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282726