Conceptualizing Party Financing Legislation in Malaysia ~ 35 ~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Program Progressive Alliance Conference: Social Justice and Sustainability for a Fair and Prosperous World 25 – 26 May 2017, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Draft Program Progressive Alliance Conference: Social Justice and Sustainability for a Fair and Prosperous World 25 – 26 May 2017, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia 25 May 2017 Venue: Shangri-La Hotel, Ulaanbaatar 19 Olympic Street, Sukhbaatar-1 Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia 14241 (+976) 7702 9999 88023167 www.shangri-la.com From 08:00 hrs Registration 09:00 hrs Steering Committee (Room 1 with interpretation Mongolian and English) All parties and associated organisations of the Progressive Alliance are entitled to send delegates to the Steering Committee. The Steering Committee prepares the convention, discusses resolutions and the upcoming activities of the Progressive Alliance. Chaired by Konstantin Woinoff, Coordinator, Progressive Alliance Welcome by the Mongolian People's Party (MPP) . Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai , Member of Parliament, Mongolian People's Party (MPP), Mongolia, Member of the Board of the Progressive Alliance Introduction into the program . Marie Chris Cabreros, Coordinator, Network of Social Democracy in Asia (SocDem Asia) Introduction into the input paper . Conny Reuter, Secretary General, Solidar Introduction into the SocDem Asia - GPF Paper on Building Open and Safe Societies for All . Doriano Dragoni, Secretary General, Global Progressive Forum (GPF) Report on the recent developments in Palestine and Israel . Faraj Zayoud, Fatah, Palestine . Einat Ovadia, Meretz Party, Israel 10:00 hrs Coffee Break 10:30 hrs Parallel Breakout Sessions Breakout Session 1: Developing situation in Asian countries (Room 1 with interpretation Mongolian and English) Chaired by Marie Chris Cabreros, Coordinator, Network of Social Democracy in Asia (SocDem Asia), Member of the Board of the Progressive Alliance . Zandanshatar Gombojav, Member of Parliament, Mongolian People's Party (MPP), Mongolia 2 . Dusmanta Kumar Giri, Secretary General, Association for Democratic Socialism (ADS), India . -

Socio-Cultural Effects and Meanings of Small-Scale Festivals: Pesta Pinji

SOCIO-CULTURAL EFFECTS AND MEANINGS OF SMALL- SCALE FESTIVALS: PESTA PINJI Master Thesis Estefanya Gordillo SOCIO-CULTURAL EFFECTS AND MEANINGS OF SMALL- SCALE FESTIVALS: PESTA PINJI MASTER THESIS Msc. Leisure Tourism and Environment Estefanya Gordillo Loyola Reg. Number 870918270040 Thesis Supervisor Dr. Meghann Ormond (Cultural Geography Group) Examiner Dr. Rene van der Duim (Cultural Geography Group) Wageningen University Research center Master of Leisure Tourism and Environment st 31 of August, 2015 SUMMARY The participation of communities in a festival is more and more common bringing economic, political, social, cultural and environmental effect on the community. While some communities are looking forward getting economic resources from an event, some others are looking for political and cultural recognition from the rest of their society. Different studies have shown the socio-cultural effects of events, as festivals, related to enhancing cultural pride, community participation and communication, awareness of the culture, new knowledge for the community, between many others. In general, the aim of community festivals is to celebrate the culture of the community; thus social and cultural benefits are achieved in the process of staging the event. One cultural element of a community is food, between many others. Food is understood as belonging to foodways which means the integration of culinary smells, ingredients, sights, and landscapes, sounds, eating practices, and farming traditions of people or a region (Timonthy & Ron, 2013; van Westering, 1999). For that reason by acknowledging food, tradition and living traditions are recognized the symbolism and social differences between cultures. This cultural element is applicable to events, and it has been used in forms of food festivals. -

PERAK P = Parlimen / Parliament N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) / State Constituencies

PERAK P = Parlimen / Parliament N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) / State Constituencies KAWASAN / STATE PENYANDANG / INCUMBENT PARTI / PARTY P054 GERIK HASBULLAH BIN OSMAN BN N05401 - PENGKALAN HULU AZNEL BIN IBRAHIM BN N05402 – TEMENGGOR SALBIAH BINTI MOHAMED BN P055 LENGGONG SHAMSUL ANUAR BIN NASARAH BN N05503 – KENERING MOHD TARMIZI BIN IDRIS BN N05504 - KOTA TAMPAN SAARANI BIN MOHAMAD BN P056 LARUT HAMZAH BIN ZAINUDIN BN N05605 – SELAMA MOHAMAD DAUD BIN MOHD YUSOFF BN N05606 - KUBU GAJAH AHMAD HASBULLAH BIN ALIAS BN N05607 - BATU KURAU MUHAMMAD AMIN BIN ZAKARIA BN P057 PARIT BUNTAR MUJAHID BIN YUSOF PAS N05708 - TITI SERONG ABU BAKAR BIN HAJI HUSSIAN PAS N05709 - KUALA KURAU ABDUL YUNUS B JAMAHRI PAS P058 BAGAN SERAI NOOR AZMI BIN GHAZALI BN N05810 - ALOR PONGSU SHAM BIN MAT SAHAT BN N05811 - GUNONG MOHD ZAWAWI BIN ABU HASSAN PAS SEMANGGOL N05812 - SELINSING HUSIN BIN DIN PAS P059 BUKIT GANTANG IDRIS BIN AHMAD PAS N05913 - KUALA SAPETANG CHUA YEE LING PKR N05914 - CHANGKAT JERING MOHAMMAD NIZAR BIN JAMALUDDIN PAS N05915 - TRONG ZABRI BIN ABD. WAHID BN P060 TAIPING NGA KOR MING DAP N06016 – KAMUNTING MOHAMMAD ZAHIR BIN ABDUL KHALID BN N06017 - POKOK ASSAM TEH KOK LIM DAP N06018 – AULONG LEOW THYE YIH DAP P061 PADANG RENGAS MOHAMED NAZRI BIN ABDUL AZIZ BN N06119 – CHENDEROH ZAINUN BIN MAT NOOR BN N06120 - LUBOK MERBAU SITI SALMAH BINTI MAT JUSAK BN P062 SUNGAI SIPUT MICHAEL JEYAKUMAR DEVARAJ PKR N06221 – LINTANG MOHD ZOLKAFLY BIN HARUN BN N06222 - JALONG LOH SZE YEE DAP P063 TAMBUN AHMAD HUSNI BIN MOHAMAD HANADZLAH BN N06323 – MANJOI MOHAMAD ZIAD BIN MOHAMED ZAINAL ABIDIN BN N06324 - HULU KINTA AMINUDDIN BIN MD HANAFIAH BN P064 IPOH TIMOR SU KEONG SIONG DAP N06425 – CANNING WONG KAH WOH (DAP) DAP N06426 - TEBING TINGGI ONG BOON PIOW (DAP) DAP N06427 - PASIR PINJI LEE CHUAN HOW (DAP) DAP P065 IPOH BARAT M. -

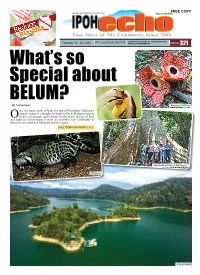

Ipoh Echo Issue

FREE COPY PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – February 16 - 29, 2020 ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR ISSUE 321 What’s so Special about BELUM? By Vivien Lian Blooming Rafflesia nly two hours north of Ipoh lies one of Peninsular Malaysia’s natural treasures, a hotspot for biodiversity in Malaysia hosting Odiverse ecosystems and habitats for the many species of flora and fauna of which many of them are endemic, rare, vulnerable or otherwise threatened in Malaysia and the region. FULL STORY ON PAGES 2 & 6 Enormous old tree in Temenggor Wild civet Khong Island YOUR VOICE IN THE COMMUNITY 2 IE321 February 16 - 29, 2020 www.ipohecho.com.my Ipoh Echo Foodie Guide Ipoh Echo Something for everyone, from the intrepid to the laid back 2 Pillbox Jahai tribe of Orang Asli oyal Belum is famous for its state park which was With a variety of waterfalls, indigenous villages, gazetted as a protected area on May 3, 2007, under salt-licks, interesting plants, animals and insects, there Rthe Perak State Parks Corporation Enactment is much to do and it is this rich biodiversity that attracts 2001. The 130-million-year-old rainforest covering local and foreign visitors who flock to Royal Belum. 117,500 hectares is amongst the oldest in the world, vying Salt licks are natural salt deposits which animals for seniority with the forests of the Amazon, Congo, and regularly lick to get their much-needed mineral others. sustenance. Wild animals often leave their faeces around Consisting mainly of primary forests, it boasts the place to mark their territory. -

IS IPOH PEDESTRIAN-FRIENDLY? by Nabilah Hamudin Eceiving Accolades and Attention Internationally Is No Reason for Ipoh to Stop Recognising Its Flaws and Shortcomings

FREE COPY August 1 - 15, 2018 PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR ISSUE 286 100,000 print readers Bimonthly 937,211 online hits (Jun) – verifiable IS IPOH PEDESTRIAN-FRIENDLY? By Nabilah Hamudin eceiving accolades and attention internationally is no reason for Ipoh to stop recognising its flaws and shortcomings. Plenty more can be done by Rthe authorities and Ipohites alike to improve living conditions of the city’s citizens. In this issue of Ipoh Echo we shall focus on pedestrian-friendly facilities and amenities available for all and sundry. Continued on page 2 Students endanger themselves crossing the road Pedestrians reluctant to use overhead bridge 3D pedestrian crossing near Medan Kidd MASCOT DESIGN CONTEST n conjunction with Visit Malaysia Year 2020, Tourism Perak is organising a IWOW PERAK mascot design contest beginning July 15 till August 15 this year. Tan Kar Hing, Executive Councillor for Tourism, Arts and Culture believes that Perakeans are not only talented but also creative and are able to produce ideas for contests like this. “We welcome everyone to take part in the competition because we believe Perakeans are an innovative lot capable of creating a unique and pretty mascot for Perak. The selected design would become the state tourism icon and be used in official programmes of the state government. The new mascot is hoped to create a new image and as a breath of fresh air for the Perak tourism industry,” he explained. “The co-sponsors for the competition are Movie Animation Park Studios (MAPS), Menteri Besar Incorporated (MB Inc), Syeun Hotel, Kellie’s Castle and Bukit Merah Resort,” he added. -

SEP 2019 Message from the VC

UTPQuarterly ISSUE 71ISSN 1675 - 2023 I JUL - SEP 2019 Message From The VC Hello again everyone. It is with great pleasure that I greet you once again in our third edition of our Quarterly newsletter, for 2019. This newsletter is pivotal in keeping us all up-to- date with the many happenings at UTP each day, while bringing us satisfaction that our labours are producing fruit. This time round, one of the exciting highlights was the visit from our alumni, YB Yeo Bee Yin. She has indeed done us proud with her accomplishments and her contributions as Malaysia’s Minister of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change. YB Yeo’s visit to UTP was indeed a great morale booster and we are proud to call her an alumni of UTP, a role model for present and future students of UTP. We also celebrate many inaugural wins, prestigious awards, medals in research and science as well as sports, and various tie-ups with strategic partners which will help to propel us further towards our goal. We have excelled in debate, leadership, innovation and games - all of which bear testament to UTP’s focus on nurturing well-rounded graduates who not only do well in academics, but also demonstrate well- honed soft skills and other must-have attributes for success. These recognitions and awards not only become the icing on the cake for us, more importantly they are success stories which show us that we are on the right track. Moving forward, we continue to excel and we continue to strive for betterment. -

PUTUS SUDAH KASIH SAYANG? Etika Umat Islam Sedang Meng- Besarnya Adalah Gelandangan

www.roketkini.com DITUBUHKAN PADA 1966 DI KUALA LUMPUR EDISI BM JULAI/OGOS 2014 facebook.com/roketkini twitter.com/roketkini [email protected] www.dapmalaysia.org PERCUMA KDN PP11723/1212012 (032229) Dapur Jalanan sedia DAP kecam larangan puasa EKSKLUSIF: Merdeka dari hadapi saman > 3 kerajaan China > 12 mata orang muda > 8,9 Menteri BN halang sedekah PUTUS SUDAH KASIH SAYANG? etika umat Islam sedang meng- besarnya adalah gelandangan. langkah yang bakal diambil ber- Kegagalan melibatkan organisasi Khayati bulan Ramadan penuh ke- Pengumuman Tengku Adnan tujuan membantu gelandangan bukan-kerajaan bukan saja menye- berkatan, Menteri Wilayah Per- pada 1 Julai lalu itu dikecam banyak secara lebih tersusun. Namun, babkan penyelesaian menyeluruh sekutuan Datuk Seri Tengku Adnan pihak sebagai tidak berperikema- kritikan timbul kerana, seperti bi- mungkin tidak terhasil, malah ia Tengku Mansor mengumumkan nusiaan dan membelakangi hak asa, kerajaan gagal melibatkan akan lebih memburukkan keadaan kerajaan akan mengenakan huku- politik golongan kurang bernasib kelompok aktivis sosial yang telah kerana tindakan yang dirancang man terhadap pemberi dan pe- baik di ibu kota. lama beroperasi di lapangan untuk bakal mencabul hak dan kebeba- nerima sedekah yang sebahagian Pihak berkuasa menjelaskan membantu golongan terbabit. san gelandangan. 2 EDISI BAHASA MALAYSIA JULAI/OGOS 2014 MENGIMBAS TRAGEDI 13 MEI Muhyiddin layak jadi idola Biarpun tragedi 13 Mei 1969 telah 45 tahun berlalu, namun sehingga kini pimpinan Umno- BN masih tetap mengapi-api perkara -

Negeri Sembilan, Melaka, Johor, Pahang, Sabah and Sarawak

business IN action @ FMM JAN – MAR 2019 VOL 1/2019 www.fmm.org.my KDN NO.PP 16730/08/2012 (030376) Challenging Times A heavy toll placed on global manufacturing as slower growth and contraction sets in "e Communicator Tech Talk Using Instagram for Establishing an business purposes ecosystem for IoT to + PG 17 thrive in Malaysia PG 23 Malaysian economy Brand Builder projected to grow Simple and e"ective FMM MIER Business anything from 4.5% tips to build your Conditions Survey to 4.9% in 2019 company branding PG 28 PG 12 PG 20 &RYHULQGG 30 Contents JANUARY - MARCH 2019 VOLUME 1/2019 PRESIDENT’S 3 MESSAGE COVER STORY: 4 CHALLENGING TIMES The US-China trade war is putting a toll on manufacturing countries as slower growth and contraction sets in BUSINESS 12 FEATURE: STILL UPBEAT ABOUT THE ECONOMY Malaysia is forecast to grow anything from 4.5% to 4.9% in 2019 THE 17 COMMUNICATOR: USING INSTAGRAM FOR BUSINESS Posted visuals remain a strong messaging PAGE method for companies to use to boost customer engagement, customer 4 search and sales BRAND BUILDER: DATA INFORMER: 20 EFFECTIVE 25 ECONOMIC BRAND BUILDING PROSPECTS FOR 2019 Simple guidelines to build The Organisation for your company and its Economic Co-operation products and Development (OECD) maps future scenarios for TECH TALK: ASEAN-5 countries 23 ESTABLISHING AN ECOSYSTEM FOR FMM-MIER IOT TO THRIVE 28 BUSINESS Stakeholders in the ICT CONDITIONS SURVEY: PAGE industry are working MANUFACTURING together to create an ideal PICKS UP IN 2018, platform for the technology EXPECTS TO SLOW 12 -

THE FUTURE of WORK in the NEW NORMAL 12-16 October 2020 (Monday-Friday) 15.00 - 17.30 (Kuala Lumpur, GMT+8)

Web Conference Regional Conference #EconomyOfTomorrow THE FUTURE OF WORK IN THE NEW NORMAL 12-16 October 2020 (Monday-Friday) 15.00 - 17.30 (Kuala Lumpur, GMT+8) 09:00 - Berlin, Brussels, Switzerland (GMT + 2) 12:00 - Pakistan (GMT + 5) 12:30 - India (GMT + 5:30) 14:00 - Indonesia (Jakarta), Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand (GMT + 7) 15:00 - Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, Phillipines (GMT + 8) 16:00 - Japan, South Korea (GMT + 9) Regional Conference THE FUTURE OF WORK IN THE NEW NORMAL #EconomyOfTomorrow Content / Background & Priorities 2 / Priorities 4 / Programme 5 / Role Players 15 / Organizers 30 / Notes 33 Regional Conference THE FUTURE OF WORK IN THE NEW NORMAL #EconomyOfTomorrow Background & Priorities Originated as a public health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic has also developed into a global economic crisis, with severe and potentially lasting impacts on economic activity, trade, employment, and the world of work. Beyond the tragic loss of human life, the multidimensional crisis will likely inflict a tremendous human cost in many other ways, like increasing poverty, long-term debt and inequality as well as unemployment, and affecting even more those who are already vulnerable. Recent estimates by the Asian Development Bank suggest that job losses in Asia could go up to 68 Million. Initially, both white-collar, but especially blue-collar workers, have been affected by the pandemic to an unimaginable degree. They have had to cope with a lack of protection at work, concerns inadequate childcare or worries about their immigration status. But the divide between white collars workers, who could work from home and blue-collar workers, who still are exposed to health risks outside, became obvious in recent months. -

Senarai Calon Pakatan Pembangkang Di Perak Bernama 18 April, 2013

Senarai Calon Pakatan Pembangkang Di Perak Bernama 18 April, 2013 IPOH, 18 April (Bernama) -- Berikut ialah senarai penuh calon pakatan pembangkang DAP, Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) dan PAS bagi 24 kerusi Parlimen dan 59 Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) di Perak untuk pilihan raya umum ke-13 yang diumumkan Khamis malam. PARLIMEN Gerik: Norhayati Kassim (PAS) Lenggong: Razman Zakaria (PAS) Larut: Mohd Fauzi Shaari (PAS) Parit Buntar: Mujahid Yusof Rawa (PAS) Bagan Serai: Muhammad Nur Manuty (PKR) Bukit Gantang: Idris Ahmad (PAS) Taiping: Nga Kor Ming (DAP) Padang Rengas: Meor Ahmad Isharra Ishak (PKR) Sungai Siput: (belum disahkan) Tambun: Siti Aishah Shaik Ismail (PKR) Ipoh Timor: Su Keong Siong (DAP) Ipoh Barat: M Kula Segaran (DAP) Batu Gajah: Sivakumar Varatharaju (DAP) Kuala Kangsar: Khalil Idham Lim (PAS) Beruas : Ngeh Koo Ham (DAP) Parit: Mohamad Ismi Muhamad Taib (PAS) Kampar: Ko Chung Sen (DAP) Gopeng: Lee Boon Chye (PKR) Tapah: Vasantha Kumar Krishan (PKR) Pasir Salak: Mustafa Kamil Ayyub (PKR) Lumut: Laksamana Pertama (B) Mohamad Imran Abdul Hamid (PKR) Bagan Datoh: Madzi Hassan (PKR) Teluk Intan: Seah Leong Peng (DAP) Tanjung Malim: Tan Yee Kew (PKR) NEGERI Pengkalan Hulu: Mejar (B) Abdullah Masnan (PKR) Temengor: Mohd Supian Nordin (PKR) Kenering: Mohd Tarmizi Abdul Hamid (PKR) Kota Tampan: Zahrul Nizam Abdul Majid (PKR) Selama: Mohd Akmal Kamaruddin (PAS) Kubu Gajah: Mohd Nazri bin Din (PAS) Batu Kurau: Mohd Fadzil Alias (PKR) Titi Serong: Abu Bakar Hussain (PAS) Kuala Kurau: Abdul Yunus Jamhari (PKR) Alor Pongsu: Rosli Ibrahim (PKR) Gunung Semanggol: Mohd Zawawi Abu Hassan (PAS) Selinsing: Husin Din (PAS) Kuala Sepetang: Chua Yee Ling (PKR) Changkat Jering: Datuk Seri Mohamad Nizar Jamaluddin (PAS) Trong: Norazli Musa (PAS) Kamunting: Mohamad Fakhrudin Abdul Aziz (PAS) Pokok Assam: Teh Kok Lim (DAP) Aulong: Leow Thye Yih (DAP) Chenderoh: Mohamad Azalan Mohamad Radzi (PAS) Lubuk Merbau: Mohd Zainudin Mohd Yusof (PAS) Lintang: Mej (B) Ir. -

Download Ipoh Echo Issue

www.ipohecho.com.my Foodie’s Guide FREE COPY to Ipoh’s Best Eats Get your copy from Ipoh Echo’s office or Meru Valley Golf Club IPOH members’ desk. (See page 5 for other echoechoYour Voice In The Community places available.) September 16-30, 2013 PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – ISSUE RPP RM29 ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR 174 Page 3 Page 4 Page 9 Page 12 Happy Is This Merdeka First Sitting of Malaysia Possible? Round-Up Perak’s 13th State Day? Assembly Session By Emily Lowe OpportunitiesJOB uring the ‘60s and ‘70s when tin and rubber were the mainin contributors Perak to Malaysia’s commodity-based economy, Perak was considered the second most prosperous state in the country, after Selangor, in terms of per capita income. Besides Ipoh, towns like Kampar, Bidor and Taiping were vibrant, often associated Dwith millionaires and Mercedes Benzes. With the collapse of the world tin industry in the early 1980s, Perak saw a turn of fortune. The closure of tin mines affected livelihood and this forced many to migrate overseas to seek greener pastures. The trend has since continued, with most choosing to remain where they pursued tertiary education. Continued on page 2 Fundraiser Operetta by Australian Troupe poh theatre lovers will be in for a treat at the end of this month when the Johann Strauss operetta, Die Fledermaus or ‘The Revenge of The Bat’ will be performed here by Australia’s Touring Opera Company, Co-Opera. I The operetta is being brought in by the Perak Association for the Intellectually Disabled (PAFID) as part of its annual fund raising project in collaboration with Co-Opera. -

Sektor Pelancongan Anggar Rugi RM105 Juta, Sektor Perniagaan

E-dagang bantu peniaga kecil Selangor terjejas ketika Covid-19 SelangorKini.my 15 Mei 2020 by Norrasyidah Arshad SHAH ALAM, 15 MEI: Peniaga kecil tidak mengharapkan bantuan modal semata- mata sebaliknya mereka turut memerlukan platform berniaga untuk terus maju ketika penularan Covid-19, kata Dato’ Menteri Besar. Dato’ Seri Amirudin Shari berkata susulan itu Kerajaan Selangor akan terus menyediakan peluang perniagaan e-dagang dengan lebih meluas selain bantuan modal dan ilmu perniagaan ketika musim Covid-19 dan selepas wabak. “Saya percaya peniaga bukan hanya berdepan masalah wang untuk menampung mereka namun paling penting adalah bagaimana mahu sediakan ruangan baharu untuk mereka,” kata beliau ketika menjadi panel Wacana Post Covid-19 menerusi siaran langsung Facebook malam tadi. Turut sama dalam program kendalian Ahli Dewan Undangan Negeri Pasir Pinji di Perak iaitu Howard Lee Chuan How ialah Ketua Menteri Pulau Pinang Chow Kon Yeow dan Menteri Besar Kedah Datuk Seri Mukhriz Mahathir. Amirudin berkata, keperluan aspek itu dapat dilihat menerusi pelaksanaan program e- Bazar Raya Selangor dengan kerjasama pengendali e-dagang terkemuka, Shopee apabila sasaran 2,000 peserta tercapai hanya dalam beberapa hari. “Jadi sekarang bukan hanya isu modal tetapi bagaimana untuk ubah peniaga daripada mengendalikan jualan langsung ke dalam talian. E-dagang platform yang besar dan akan bantu ekonomi Kerajaan Negeri,” katanya. Bulan lalu Kerajaan Negeri dengan kerjasama Shopee mengumumkan program e- Bazar Raya Selangor dengan menawarkan peluang perniagaan kepada usahawan perusahaan kecil dan sederhana (PKS) serta perniagaan mikro memasarkan produk secara dalam talian. Usaha itu bagi membantu mereka menjana pendapatan ketika musim perayaan ekoran terjejas akibat Covid-19. © Copyright 2019 - Developed for the People of Selangor Source: https://selangorkini.my/2020/05/e-dagang-bantu-peniaga-kecil-selangor- terjejas-ketika-covid-19/ .