Urushi Art Techniques in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fields Corporation Digital Annual Report 2017

FIELDS CORPORATION Annual Report 2017 April 1, 2016 – March 31, 2017 DIGITAL ANNUAL REPORT 2017 FIELDS CORPORATION CONTENTS Management Message The Greatest Leisure for All People 02 CEO Message 01 04 COO Message Review of Business Activities Toward the enhancing IP value and improving profitability 07 Consolidated Financial Highlights 06 08 Business Results Review 10 Business Overview 15 Market Data Financial Section Consolidated Financial Statement 19 Consolidated Financial Statement 18 47 Independent Auditor’s Report CSR / Corporate Governance / Company and Stock Information For the contributing to happiness of society 49 FIELDS’ CSR 48 50 Corporate Governance 52 About FIELDS (Company Information) 55 FIELDS’ Advances 61 Stock Information Management Message The Greatest Leisure for All People FIELDS CORPORATION aim to become a company able to continuously create the greatest leisure for all people throughout the world. CONTENTS CEO Message Chairman and CEO Hidetoshi Yamamoto 02 COO Message President and COO Tetsuya Shigematsu 04 FIELDS CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2017 01 Management Message >CEO Message MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN and CEO CEO Message Greetings I would like to express my sincere appreciation for concerning the Company’s results in the last fiscal year. the understanding and continued support of our We will not waste this experience, instead, we will use shareholders, investors and all our other it to spur ourselves on to ensure vitality in the future, stakeholders. and our management and employees will strive Moreover, I would like to convey our deepest diligently in unison. apologies for any distress caused to our stakeholders The Company’s Establishment and Innovation of PS Distribution Since the foundation of FIELDS, we have become of pachinko and pachislot machines installed in integrated in the lives of many people in every region pachinko halls, the services offered, through to the across Japan, discovering unrealized potential for very format of the pachinko hall space itself. -

Keeping Watch on Intangible Cultural Heritage: Live Transmission and Sustainable Development of Chinese Lacquer Art

sustainability Article Keeping Watch on Intangible Cultural Heritage: Live Transmission and Sustainable Development of Chinese Lacquer Art Xiaoting Song 1, Yongzhong Yang 1,*, Ruo Yang 1 and Mohsin Shafi 2 1 Business School, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, China 2 School of Economics and Management, Leshan Normal University, Leshan 614000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 May 2019; Accepted: 9 July 2019; Published: 16 July 2019 Abstract: Countries all over the world have been constantly exploring ways to rescue and protect intangible cultural heritage. While learning from other countries’ protection measures, the Chinese government is also constantly exploring ways that conform to China’s national conditions. As China’s first batch of intangible cultural heritage, lacquer art boasts a brilliant history, but many people are not familiar with it today. Moreover, in the process of modernization, the lacquer art transmission is declining day by day, and it is facing unprecedented major crises such as loss and division of history into periods. Hence, it is essential to verify and reveal the challenges and dilemmas in the lacquer art transmission, and come up with corresponding protection measures around these problems. First of all, this research, through literature review, “horizontally” explores the current research status and the universal problems of lacquer art transmission from the macro level. With a view to make up for the deficiencies of the existing research and further supplement the empirical evidence, the current research, with the transmission of “Chengdu lacquer art” as an example and through in-depth interviews, tracks and investigates the whole process of transmission of Chengdu Lacquer Art Training Institute, and “vertically” analyzes the survival situation of lacquer art transmission and the core problems affecting transmission behaviors from the micro level. -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

1 Bouilloire À Eau (Tetsubin) De Forme Cylindrique Décorée D’Un Dragon Et De Nuages En Relief

1 Bouilloire à eau (tetsubin) de forme cylindrique décorée d’un dragon et de nuages en relief. Période Meiji – Taisho. H. : 17 cm; l. : 14 cm. 150 - 180 € Round cylindrical iron water-kettle (tetsubin) decorated with a dragon with clouds relief. Meiji - Taisho Period. 2 Bouilloire à eau en métal de forme plate et arrondie (tetsubin). Avec une anse fixe et un motif en bas-relief figurant des chevaux. Le couvercle arbore une poignée en forme de pomme de pin. Période Meiji. H. : 22,5 cm; D. : 21 cm. 250 - 350 € Round flat iron water-kettle (tetsubin) with a fixed handle and decorated in low relief with horses. The lid has a pine-cone shaped knob. Meiji period. 3 Bouilloire à eau (tetsubin) de forme globulaire. Motifs en relief à picots (arare). Le couvercle de cuivre affiche sur l’intérieur la marque Ryûbundô. Période Meiji. l. : 17,5 cm; D. : 16,5 cm 280 - 320 € Globular iron water-kettle (tetsubin) decorated with hailstone (arare) motive. Copper lid marked at the inside Ryûbundô. Meiji Period. 4 Bouilloire à eau (tetsubin) en métal de forme ronde. Motifs en relief à picots (arare). Période Meiji – Taisho. l. : 20 cm; D. : 14 cm. 200 - 250 € Round iron water-kettle (tetsubin) decorated with hailstone (arare) motive. Meiji - Taisho Period. 5 Bouilloire à eau en métal (tetsubin). L’objet arbore un couvercle et des anses en laiton et des décors en relief figurant des phénix. Période Meiji – Taisho. l. : 19 cm; D. : 15 cm. 350 - 450 € Iron water-kettle (testubin) with brass lid and handle and decorated with a relief of phoenixes. -

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014 - August 2016 *To search for items, please press Ctrl + F and enter the title in the search box at the top right hand corner or at the bottom of the screen. LEGEND : BK - Book; AL - Adult Library; YPL - Children Library; AV - Audiobooks; FIC - Fiction; ANF - Adult Non-Fiction; Bio - Biography/Autobiography; ER - Early Reader; CFIC - Picture Books; CC - Chapter Books; TOD - Toddlers; COO - Cookbook; JFIC - Junior Fiction; JNF - Junior Non Fiction; POE -Children's Poetry; TRA - Travel Guide Type Location Collection Call No Title AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GIL Big magic : Creative living / Elizabeth Gilbert. AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GRA Originals : How non-conformists move the world / Adam Grant. Irrationally yours : On missing socks, pick up lines, and other existential puzzles / Dan AV AL ANF CD 153.4 ARI Ariely. Think like a freak : The authors of Freakonomics offer to retrain your brain /Steven D. AV AL ANF CD 153.43 LEV Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. AV AL ANF CD 153.8 DWE Mindset : The new psychology of success / Carol S. Dweck. The geography of genius : A search for the world's most creative places, from Ancient AV AL ANF CD 153.98 WEI Athens to Silicon Valley / Eric Weiner. AV AL ANF CD 158 BRO Rising strong / Brene Brown. AV AL ANF CD 158 DUH Smarter faster better : The secrets of prodctivity in life and business / Charles Duhigg. AV AL ANF CD 158.1 URY Getting to yes with yourself and other worthy opponents / William Ury. 10% happier : How I tamed the voice in my head, reduced stress without losing my edge, AV AL ANF CD 158.12 HAR and found self-help that actually works - a true story / Dan Harris. -

Inheritance, Protection and Innovative Development of China's Intangible Cultural Heritage—Carved Lacquerware

https://doi.org/10.37420/icaces.2020.031 Inheritance, Protection and Innovative Development of China's Intangible Cultural Heritage—Carved Lacquerware Desai Jiang, Yue Xu College of Arts, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin 541006, China Abstract: This paper studies the protection and inheritance of this precious China’s intangible cultural heritage from the aspects of carving lacquer technology, personnel training and innovation. Focusing on the protection of carving lacquer technology and the innovation in the design and production of carved lacquer handicrafts, it is proposed to protect the carving lacquer technology from three aspects which is intellectual property right, personnel training and raw material. In terms of technical innovation, the possibility of combining carved lacquer with various materials is studied and analyzed. Keywords: Carved lacquer; Arts and crafts; Lacquerware; Intangible cultural heritage 1 Introduction Carved lacquer is a unique category of arts and crafts in China. It can also be called Tihong, Tihuang,Tihei,Ticai and Tixi, because of its different colors. Among them, Beijing carved lacquerware is the most representative example, and has many quality products in the world. Carved lacquer has a long history. According to records, it can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty. The Yuan Dynasty carved lacquer gradually flourished, and the Ming and Qing Dynasties were its heyday of development. Carved lacquer handicrafts have won many awards in international expositions and earned a lot of foreign exchange for the country in special period. In 2006, carved lacquer was listed in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritage list in China. Unfortunately, since the 1990s, the carved lacquer industry has gradually shrunk, as the number of employees is extremely reduced and the trend is aging, cause the inheritance of skills has seriously broken down. -

Analysis of Artistic Characteristics of Chu Lacquerworks

2018 International Conference on Education, Management and Social Science (EMSS 2018) ISBN: 978-1-60595-554-4 Analysis of Artistic Characteristics of Chu Lacquerworks Han-Qing Ge Abstract: Chu lacquer has become the representative of lacquer art in the Warring States Period because of its variety and excellent production. This article elaborates its unique artistic features through the analysis of the selection, types and modeling arts, colors, decoration and other aspects of Chu lacquer ware. Keyword: Chu Lacquerware, Fetus, types and shapes, decorative techniques, patterns Chu State is a country with a long history and amazing color in Chinese history. During the Warring States period, only the Chu State could contend with the Qin State and there was a trend of being divided by the world with Qin. According to "Huainanzi • soldier slightly training" records, "South Juan Yuan Xiang, north around Ying Si, West Bao Ba Shu, East Huai Huai, Ying Ru thought , Jianghan that pool, Yuan to Deng Lin, cotton with Fangcheng, Chu's strong, the earth in public, in points world. "Thus, Chu territory was almost covered the entire southern region. At present, the construction of major provincial capital cities in central and southern China all have the credit of the Chu Kingdom. At the same time, the Chu culture has gradually infiltrated into various places. Most of the lacquer wares from the Warring States Period come from the Chu Tomb. During this period, the lacquer ware manufacturing industry entered an unprecedented prosperity stage. It is the first peak of the development of Chinese lacquer ware art. There are three reasons for this: First, Chu is located in a warm and humid subtropical region, 15 degrees Celsius temperature and 1100 mm rainfall, even if the production process of lacquer simplification, but also easy to form a high-quality film. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Secondary Fiber Recycling 01993 TAPPI PRESS Atlanta. Georgia iii Preface v List of Contributors vii Table of Contents ix List of Figures and Tables Chapter 1 Recovered Paper and the U.S. Solid Waste Dilemma I 1 by Rodney Young Introduction and Overview ............................................ 1 Paper Industry Response to the Solid Waste Issue ................................ 2 U.S. Recovered Paper Consumption ..................................... 2 U.S. Trade in Recovered Paper ........................................ 3 U.S. Recovered Paper Recovery ....................................... 3 Recovered Paper Supply and Cost ...................................... 3 Bibliography .................................................... 4 Resources ................................................... 4 Chapter 2 Recycled- Versus Virgin-Fiber Characteristics: A Comparison 1 7 by R. L. Ellls and K. M. Ssdlachsk Introduction ..................................................... 7 Literature Review ................................................. 8 General Effect of Recycling ......................................... 8 Effect of Furnish .............................................. 10 Effect of initial Beating of Virgin Pulp ................................... 10 Theory for Tensile Strength of Paper .................................... 10 First Assumption ............................................ 11 Second Assumption .......................................... 12 Theory Verification ............................................ -

Sailor 1911 KOP Ad Out

Superlatives BY BARRY GABAY Appropriate Here Writing instruments from AP Limited Editions are a blend of influences and techniques, reflecting our multicultural world. Top two rows—examples of AP Limited Editions urushi and maki-e writing instruments. Bottom two rows—the company’s work in Russian lacquer art. >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> 46 e must reserve the use of adjectives for them to have any meaning or substance. WWe hear “amazing” countless times—so often, in fact, that it has entirely lost its original meaning of “being overwhelmed by sudden surprise.” Today, the word merely signifies “very good.” I hesitate to make the claim that follows, but from a long lifetime of usage, I have encountered a fair number of fountain pens. So here goes: the pens offered for the eyes of all and the hands of a fortunate few by AP Limited Editions are among the most beautiful and functional pens in the world. Period. Approaching an AP Limited Editions pen is entirely different from grabbing a favorite daily writer; but these gallery-quality art pens are meant to be used. Anuj and Smita Poddar, founders and owners of AP, are serious pen users and collectors and want to share both those aspects of writing culture. Why should a luxury model intended for writing sit unused on a shelf? The fountain pens and rollerballs produced by AP Limited Editions are among the greatest in their category, a realm that merges fine art and utility. These pens are exquisite but are also meant for writing. The fountain pens are eyedropper or cartridge/converter fillers (with new bulk fillers recently released) fitted with 18 karat gold nibs in a wide range of grades from Bock, the famed German nib maker. -

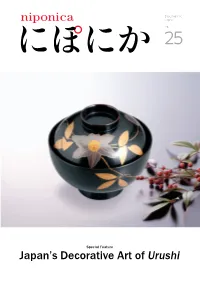

Urushi Selection of Shikki from Various Regions of Japan Clockwise, from Top Left: Set of Vessels for No

Discovering Japan no. 25 Special Feature Japan’s Decorative Art of Urushi Selection of shikki from various regions of Japan Clockwise, from top left: set of vessels for no. pouring and sipping toso (medicinal sake) during New Year celebrations, with Aizu-nuri; 25 stacked boxes for special occasion food items, with Wajima-nuri; tray with Yamanaka-nuri; set of five lidded bowls with Echizen-nuri. Photo: KATSUMI AOSHIMA contents niponica is published in Japanese and six other languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish) to introduce to the world the people and culture of Japan today. The title niponica is derived from “Nippon,” the Japanese word for Japan. 04 Special Feature Beauty Created From Strength and Delicacy Japan’s Decorative Art 10 Various Shikki From Different of Urushi Regions 12 Japanese Handicrafts- Craftsmen Who Create Shikki 16 The Japanese Spirit Has Been Inherited - Urushi Restorers 18 Tradition and Innovation- New Forms of the Decorative Art of Urushi Cover: Bowl with Echizen-nuri 20 Photo: KATSUMI AOSHIMA Incorporating Urushi-nuri Into Everyday Life 22 Tasty Japan:Time to Eat! Zoni Special Feature 24 Japan’s Decorative Art of Urushi Strolling Japan Hirosaki Shikki - representative of Japan’s decorative arts. no.25 H-310318 These decorative items of art full of Japanese charm are known as “japan” Published by: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 28 throughout the world. Full of nature's bounty they surpass the boundaries of 2-2-1 Kasumigaseki, Souvenirs of Japan Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8919, Japan time to encompass everyday life. https://www.mofa.go.jp/ Koshu Inden Beauty Created From Writing box - a box for writing implements. -

Program 1St Day June 25, 2016

Program 1st day June 25, 2016 9:30~ Open 10:25~10:35 Opening Address (◎ Principal investigator, Presenter ○ Presenter) Session Ⅰ The chairman: AKIYAMA Junko (Kyushu National Museum), WADA Hiroshi (Tokyo National Museum) 10:40~11:00 A gas-phase conservation process of acidic papers using ethanolamines ◎ OKAYAMA Takayuki (Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology), IWABUCHI Masayuki (Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology) 11:00~11:20 Research on Gaseous Ammonia in an Exhibition Room of Museum Measured by Gas Detector Tube ◎ SUGIZAKI Sahoe (Fukushima Museum), YAMAZAKI Masahiko (Komyo Rikagaku Kogyo K.K.), MATSUDA Takatsugu (Tohoku Gakuin University) 11:20~11:40 Deformation of packing foam under carbon dioxide treatment ◎ FUTAMATA Satoshi (NIPPON EKITAN Corporation), HIDAKA Shingo (National Museum of Ethnology), SUEMORI Kaoru (National Museum of Ethnology), WADAKA Tomomi (LLC Bunkasozokougei), KAWAMURA Yukako (Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property), HASHIMOTO Sachi (Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property), YOSHIMURA Kenji (NIPPON EKITAN Corporation) 11:40~12:00 Investigation of pest control for medical inheritance: The research of Koan Ogata's medicine chest ◎ TAKAURA-SHIMADA Kayoko (The Museum of Osaka University), TAKAHASHI Kyoko (The Museum of Osaka University), OGURI Kazuki (Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Osaka University), MURATA Michihito (Graduate School of Letters, Osaka University) 12:00~13:00 Lunch break 13:00~14:00 Poster session Session Ⅱ The chairman: ARAI Kei (Tokyo University -

Lacquerware Chemistry

Chemistry the key to our future Lacquerware Sake cup of Wajima-nuri Wajima-nuri 輪島塗Lacquerware The lacquerwares made in Wajima City, Ishikawa Japanese lacquerware is believed to have a history Prefecture are called wajima-nuri, or wajima of around 6800 years, and the oldest lacquerware lacquerware, which is prepared by repeatedly has been excavated in Ishikawa. Some of the covering wood or paper with lacquer. The lacquer reasons why lacquering has flourished around used for such craftworks is sap taken and processed Wajima area may have been that essential materials from Japanese lacquer trees. This natural resin for making lacquerware (tree that provides paint mainly consists of urushiol and may cause lacquer and wood for woodworks as well as good allergy. It also contains a catalyst called laccase, diatomite) were abundantly available, and that there and helps the lacquer to were also active markets thanks to the seaports be oxidized in the air and nearby. polymerize to make a real Here is how a lacquerware is made. Making of a hard coating. The climate wajima-nuri starts with obtaining a quality wooden in Japan, especially in basis. Any fragile parts are reinforced by putting Wajima, provides the desired fabric pieces using lacquer. As primer coating, humidity and temperature for mixture of lacquer and jinoko (powdered diatomite) Sap from urushi tree this polymerization reaction. is applied for more than twice, and raw lacquer is applied to further reinforce breakable points. Then middle and finish coatings of lacquer are applied before various decorative techniques, for example, makie (painting in colored lacquer) or chinkin (sunken gold).