Gezi Movement: an Analysis in the Context of Place/Space, the Discursive Practices and the Society a Thesis Submitted to the Gr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Production and Urban Locality in the Fields of Jazz and Fashion Design: the Case of Kuledibi, Istanbul

CULTURAL PRODUCTION AND URBAN LOCALITY IN THE FIELDS OF JAZZ AND FASHION DESIGN: THE CASE OF KULEDİBİ, İSTANBUL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF THE MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ALTAN İLKUÇAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2013 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof.Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Ayşe Saktanber Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Helga Rittersberger-Tılıç Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Eminegül Karababa (METU-MAN) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Helga Rittersberger-Tılıç (METU-SOC) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tahire Erman (BİLKENT-POLS) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sibel Kalaycıoğlu (METU-SOC) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Erdoğan Yıldırım (METU-SOC) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Altan İlkuçan Signature : iii ABSTRACT CULTURAL PRODUCTION AND URBAN LOCALITY IN THE FIELDS OF JAZZ AND FASHION DESIGN: THE CASE OF KULEDİBİ, İSTANBUL İlkuçan, Altan Ph.D., Department of Sociology Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Helga Rittersberger-Tılıç September 2013, 230 pages This study aims to analyze the relationship between cultural producers in Istanbul and the wider processes of neoliberal urban restructuring that takes in their surroundings. -

Case Study on Holistic Assessment of the Relationship Between City and Square

Journal of Architecture and Urbanism ISSN 2029-7955 / eISSN 2029-7947 2020 Volume 44 Issue 2: 152–165 https://doi.org/10.3846/jau.2020.11331 CASE STUDY ON HOLISTIC ASSESSMENT OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CITY AND SQUARE * Duygu TURGUT Department of Architecture, Erciyes University, Kayseri, Turkey Received 11 October 2019; accepted 13 July 2020 Abstract. While the squares have been in the network of relations with the political, social and religious structure of the soci- ety since the early days of history, today, they have been associated with the cars, speed and technology in the process formed with the modernization movement. In some squares, there are tramways, public transportation routes and stops, and there are also motor vehicles. The squares have turned into places where there is a continuous flow with fast traffic except for waiting at the bus stops and railway station. With this change, our needs also changed, and with the introduction of motor vehicles in our lives, the squares remained as neglected urban spaces in an effort to create a transportation network. The use of the squares belongs to the period in which people have habit of being together, but now squares use belongs to a period in which we are not together even if we are side by side. Within the scope of this study, nowadays, approaches and practices for the squares that is an urban space in the world have been investigated. According to the results of sections, the criteria for evaluat- ing the completeness of the city-square relationship in today’s conditions are set out in a table. -

Galata and Pera 1 a Short History, Urban Development Architecture and Today

ARI The Bulletin of the İstanbul Technical University VOLUME 55, NUMBER 1 Galata and Pera 1 A Short History, Urban Development Architecture and Today Afife Batur Faculty of Architecture, Istanbul Technical University, Taşkışla, 34437, Taksim, Istanbul, Turkey Keywords: Galata, Pera, Urban development, Architectural development The coastal band stretching from the to be more prominent starting from 10th northern shores of the Golden Horn until century onwards. The conditions that had Tophane and the slopes behing it have been created the Medieval Galata were being known as Galata since the 8th century. formed in these trading colonies. At first Formerly this area was known as Sycae Amalfi, then the Venetians and later the (Sykai), or as peran en Sykais, which Pisans had obtained special privileges from essentially means ‘on opposite shore’. the Byzantines. The Genovese, who had It is thought that Galata’s foundation established themselves on the southern preceded that of Constantinopolis. The shores of the Golden Horn as a result of archaeological finds here indicate that it their rights recognized by Emperor Manuel was an important settlement area in Comnenos I (1143-1186), were forced to Antiquity. Although its borders can not be move over to Pera on the opposite shore determined precisely, it is known that when the Venetians seized their territory during the reign of Emperor Constantin during the Latin invasion of 1204. (324 –337), it was a fortified settlement When the Latins departed from consisting of a forum, a theatre, a church, a Constantinople in 1261, the city was in harbor and bath buildings, as well as 431 complete ruins. -

Advocacy Planning in Urban Renewal: Sulukule Platform As the First Advocacy Planning Experience of Turkey

Advocacy Planning in Urban Renewal: Sulukule Platform As the First Advocacy Planning Experience of Turkey A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Community Planning of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning by Albeniz Tugce Ezme Bachelor of City and Regional Planning Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul, Turkey January 2009 Committee Chair: Dr. David Varady Submitted February 19, 2014 Abstract Sulukule was one of the most famous neighborhoods in Istanbul because of the Romani culture and historic identity. In 2006, the Fatih Municipality knocked on the residents’ doors with an urban renovation project. The community really did not know how they could retain their residence in the neighborhood; unfortunately everybody knew that they would not prosper in another place without their community connections. They were poor and had many issues impeding their livelihoods, but there should have been another solution that did not involve eviction. People, associations, different volunteer groups, universities in Istanbul, and also some trade associations were supporting the people of Sulukule. The Sulukule Platform was founded as this predicament began and fought against government eviction for years. In 2009, the area was totally destroyed, although the community did everything possible to save their neighborhood through the support of the Sulukule Platform. I cannot say that they lost everything in this process, but I also cannot say that anything was won. I can only say that the Fatih Municipality soiled its hands. No one will forget Sulukule, but everybody will remember the Fatih Municipality with this unsuccessful project. -

Turkey | Freedom House Page 1 of 8

Turkey | Freedom House Page 1 of 8 Turkey freedomhouse.org Turkey received a downward trend arrow due to more pronounced political interference in anticorruption mechanisms and judicial processes, and greater tensions between majority Sunni Muslims and minority Alevis. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) secured two electoral victories in 2014. In March, it prevailed in local elections with more than 40 percent of the vote, and in August the party’s leader, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, was elected president in the first direct elections for that post in Turkey’s history. The AKP won despite a corruption scandal implicating government ministers as well as Erdoğan and his family, which emerged in December 2013 and cast a shadow over Turkish politics throughout 2014. Erdoğan dismissed the evidence of corruption, including audio recordings, as fabrications by elements of a “parallel state” composed of followers of Fethullah Gülen, an Islamic scholar who had backed the AKP but was now accused of plotting to bring down the government. More than 45,000 police officers and 2,500 judges and prosecutors were reassigned to new jobs, a move the government said was necessary to punish and weaken rogue officials; critics claimed it was designed to stop anticorruption investigations and undermine judicial independence. Erdoğan and AKP officials spoke out against other so-called traitors, including critical journalists and business leaders as well as members of the Alevi religious minority. Media outlets bearing unfavorable coverage of the government have been closed or placed under investigation. In December, more than 30 people linked to Gülen, including newspaper editors and television scriptwriters, were arrested on charges of establishing a terrorist group; this sparked widespread protests. -

Dergi Mim 1 Deneme Yeşil

IJAUS VOLUME :1, NUMBER: 1 THE POWER AND NATURE: THE RESISTANT SUBVERSIONS SERDAR ERİŞEN Serdar Erişen, The Power and Nature: The Resistant Subversions, Middle East Technical University, ABSTRACT This is a study of the dominant power of governmental implementa=ons in spa=al prac=ces and their disregard for nature and its representa=onal values in the public sphere. It begins by making a brief men=on of the struggle for Gezi Park in Taksim Square and the reasons behind its rapid development into a social phenomenon. The ini=al emergence of the ac=vist movements in Taksim Gezi Park seem to have been a reac=on to the government-based deconstruc=on and construc=on processes and ac=ons for Taksim, as a place in the heart of the city that is well-known for social events, demonstra=ons and social ac=vi=es. The square was closed by the government, preven=ng the holding of such social ac=vi=es as the May 1 celebra=ons in 2013, despite Taksim Square being a symbol of May 1 for the demonstrators; and s=ll under re-construc=on processes, changing the spa=al organiza=on of the square. The destruc=ve nature of the government-based construc=on processes became a s=mula=ng phenomenon for the public when aoempts were made to remove the trees from Taksim Gezi Park, which was considered at the =me an act of violence of the governmental processes against the natural environment through its means and apparatuses. The government’s ac=ons spurred into ac=on not only ac=vists, but also many of the inhabitants of İstanbul and people all across Turkey, who saw Taksim Gezi Park as a unique social space for İstanbul, as a green area at the heart of the city. -

“Everywhere Is Taksim”: the Politics of Public Space from Nation-Building

JUHXXX10.1177/0096144214566966Journal of Urban HistoryBatuman 566966research-article2015 Original Research Article Journal of Urban History 1 –27 “Everywhere Is Taksim”: The © 2015 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Politics of Public Space from sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0096144214566966 Nation-Building to Neoliberal juh.sagepub.com Islamism and Beyond Bülent Batuman1 Abstract This article discusses the politics of public space through the particular example of Taksim Square in Istanbul. Tracing Taksim’s history since the early twentieth century, the article analyzes the instrumentalization of public space in nation-building, the socialization of politics within the context of postwar rapid urbanization, and the (re)politicization of public space under neoliberal Islamism. Finally it arrives at an assessment of the nation-wide antigovernment protests that centered on Taksim Square in May–June 2013. Throughout this historical examination, the politics of public space is discussed with reference to the work of Henri Lefebvre, in order to scrutinize the spatial aspects of the relation between state and society. Accordingly, the rise of democratic public space is defined as a result of the mutual interaction between two bottom-up impetuses; the immanent politics of the social (the political character of everyday life) and the socialization of the political (civil political action). Keywords public space, right to the city, banal politicization, Taksim Sqaure, Gezi Park The last days of May 2013 witnessed an unprecedented event in Istanbul. What began as a simple environmentalist protest grew rapidly and spread across the country as a result of police brutality faced by the small group of activists. It all began with the appearance of dozers in Gezi Parkı (literally “esplanade”), the seventy-year-old park adjacent to Taksim Square, the major public space in Istanbul. -

Gezi Assemblages: Emergence As Embodiment in the Gezi Movement

Gezi Assemblages: Emergence as Embodiment in the Gezi Movement INFORMATION AND KNOWLEDGE SOCIETY DOCTORAL PROGRAM UNIVERSITAT OBERTA DE CATALUNYA (UOC) Autor: Öznur Karakaş Research Group: CareNET Supervisor: Israel Rodriguez-Giralt (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya) BARCELONA December 21, 2017 1 TABLE OF MATTERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ....................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 1 ....................................................................................................................... 25 The Gezi Movement: Emerging contentious communities in-the-making ...................... 25 1.1. How were Gezi communities made? Accounting for embodied emergence of new dissident communities ............................................................................................................ 30 1.2. Some methodological concerns: how to dwell on community-making..................... 42 1.3. Conceptualizing the communities-in-the-making: From network to assemblage ... 56 CHAPTER 2 ....................................................................................................................... 70 Action in Translation: The Action Repertoire of the Gezi Movement .............................. 70 2.1. Occupation -

The Case Study of Taksim Square

Sustainable Development and Planning VII 239 The impact of information technology on open urban space: the case study of Taksim square B. Souici Ecole polytechnique d’architecture et d’urbanisme, EPAU, Algieria Abstract For centuries, city centres have provided liveability for much of urban life: shopping, civic activities, leisure, or simply for meeting and mixing. Today, city centers face real challenges; they must respond to the changing needs and demands of modern-day living; squares need to prosper in order to survive. They must compete effectively with the advances in the means of technological communication. They have always faced a degree of competition throughout their historical past, but in the last ten years the competition has increased markedly. Each square has a distinctive shape and personality. That is what makes them so rewarding to experience and so difficult to create. Vintage squares remind us of an era when good design was instinctive, and cities had a rich street life. People have always enjoyed coming together; even though this task can be accomplished by means of virtual space, the need for verbal and physical contact remains primordial and necessary. Networks, deliver information whenever and wherever people desire and allow to perform many activities without moving in the space; banking, bill-paying, shopping. Gathering places are no longer attractive; public life seems to be slipping away along with public open spaces. Dematerialization, decentralization and demobilization are factors which result from information technology use. A new urban strategy has to be implemented, and new directions have to be designed for the vitality of future urban open spaces. -

Download All Beautiful Sites

1,800 Beautiful Places This booklet contains all the Principle Features and Honorable Mentions of 25 Cities at CitiesBeautiful.org. The beautiful places are organized alphabetically by city. Copyright © 2016 Gilbert H. Castle, III – Page 1 of 26 BEAUTIFUL MAP PRINCIPLE FEATURES HONORABLE MENTIONS FACET ICON Oude Kerk (Old Church); St. Nicholas (Sint- Portugese Synagoge, Nieuwe Kerk, Westerkerk, Bible Epiphany Nicolaaskerk); Our Lord in the Attic (Ons' Lieve Heer op Museum (Bijbels Museum) Solder) Rijksmuseum, Stedelijk Museum, Maritime Museum Hermitage Amsterdam; Central Library (Openbare Mentoring (Scheepvaartmuseum) Bibliotheek), Cobra Museum Royal Palace (Koninklijk Paleis), Concertgebouw, Music Self-Fulfillment Building on the IJ (Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ) Including Hôtel de Ville aka Stopera Bimhuis Especially Noteworthy Canals/Streets -- Herengracht, Elegance Brouwersgracht, Keizersgracht, Oude Schans, etc.; Municipal Theatre (Stadsschouwburg) Magna Plaza (Postkantoor); Blue Bridge (Blauwbrug) Red Light District (De Wallen), Skinny Bridge (Magere De Gooyer Windmill (Molen De Gooyer), Chess Originality Brug), Cinema Museum (Filmmuseum) aka Eye Film Square (Max Euweplein) Institute Musée des Tropiques aka Tropenmuseum; Van Gogh Museum, Museum Het Rembrandthuis, NEMO Revelation Photography Museums -- Photography Museum Science Center Amsterdam, Museum Huis voor Fotografie Marseille Principal Squares --Dam, Rembrandtplein, Leidseplein, Grandeur etc.; Central Station (Centraal Station); Maison de la Berlage's Stock Exchange (Beurs van -

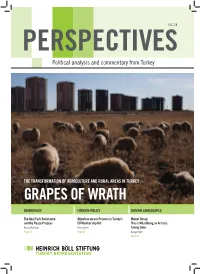

Grapes of Wrath

#6.13 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey THE TRANSFORMATION OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL AREAS IN TURKEY GRAPES OF WRATH DEMOCRACY FOREIGN POLICY HUMAN LANDSCAPES The Gezi Park Resistance Objective versus Process in Turkey’s Memet Aksoy: and the Peace Process EU Membership Bid This is What Being an Artist is: Nazan Üstündağ Erhan İçener Taking Sides Page 54 Page 62 Ayşegül Oğuz Page 66 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Contents From the editor 3 ■ Cover story: The transformation of agriculture and rural areas in Turkey The dynamics of agricultural and rural transformation in post-1980 Turkey Murat Öztürk 4 Europe’s rural policies a la carte: The right choice for Turkey? Gökhan Günaydın 11 The liberalization of Turkish agriculture and the dissolution of small peasantry Abdullah Aysu 14 Agriculture: Strategic documents and reality Ali Ekber Yıldırım 22 Land grabbing Sibel Çaşkurlu 26 A real life “Grapes of Wrath” Metin Özuğurlu 31 ■ Ecology Save the spirit of Belgrade Forest! Ünal Akkemik 35 Child poverty in Turkey: Access to education among children of seasonal workers Ayşe Gündüz Hoşgör 38 Urban contexts of the june days Şerafettin Can Atalay 42 ■ Democracy Is the Ergenekon case a step towards democracy? Orhan Gazi Ertekin 44 Participative democracy and active citizenship Ayhan Bilgen 48 Forcing the doors of perception open Melda Onur 51 The Gezi Park Resistance and the peace process Nazan Üstündağ 54 Marching like Zapatistas Sebahat Tuncel 58 ■ Foreign Policy Objective versus process: Dichotomy in Turkey’s EU membership bid Erhan İcener 62 ■ Culture Rural life in Turkish cinema: A location for innocence Ferit Karahan 64 ■ Human Landscapes from Turkey This is what being an artist is: Taking Sides Memet Aksoy 66 ■ News from HBSD 69 Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Turkey Represantation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. -

Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey

A Freedom House Special Report Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey Susan Corke Andrew Finkel David J. Kramer Carla Anne Robbins Nate Schenkkan Executive Summary 1 Cover: Mustafa Ozer AFP / GettyImages Introduction 3 The Media Sector in Turkey 5 Historical Development 5 The Media in Crisis 8 How a History Magazine Fell Victim 10 to Self-Censorship Media Ownership and Dependency 12 Imprisonment and Detention 14 Prognosis 15 Recommendations 16 Turkey 16 European Union 17 United States 17 About the Authors Susan Corke is Andrew Finkel David J. Kramer Carla Anne Robbins Nate Schenkkan director for Eurasia is a journalist based is president of Freedom is clinical professor is a program officer programs at Freedom in Turkey since 1989, House. Prior to joining of national security at Freedom House, House. Ms. Corke contributing regularly Freedom House in studies at Baruch covering Central spent seven years at to The Daily Telegraph, 2010, he was a Senior College/CUNY’s School Asia and Turkey. the State Department, The Times, The Transatlantic Fellow at of Public Affairs and He previously worked including as Deputy Economist, TIME, the German Marshall an adjunct senior as a journalist Director for European and CNN. He has also Fund of the United States. fellow at the Council in Kazakhstan and Affairs in the Bureau written for Sabah, Mr. Kramer served as on Foreign Relations. Kyrgyzstan and of Democracy, Human Milliyet, and Taraf and Assistant Secretary of She was deputy editorial studied at Ankara Rights, and Labor. appears frequently on State for Democracy, page editor at University as a Critical Turkish television.