Arctic Tern (Sterna Paradisaea) Stephen Kress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time and Tides in the Gulf of Maine a Dockside Dialogue Between Two Old Friends

1 Time and Tides in the Gulf of Maine A dockside dialogue between two old friends by David A. Brooks It's impossible to visit Maine's coast and not notice the tides. The twice-daily rise and fall of sea level never fails to impress, especially downeast, toward the Canadian border, where the tidal range can exceed twenty feet. Proceeding northeastward into the Bay of Fundy, the range grows steadily larger, until at the head of the bay, "moon" tides of greater than fifty feet can leave ships wallowing in the mud, awaiting the water's return. My dockside companion, nodding impatiently, interrupts: Yes, yes, but why is this so? Why are the tides so large along the Maine coast, and why does the tidal range increase so dramatically northeastward? Well, my friend, before we address these important questions, we should review some basic facts about the tides. Here, let me sketch a few things that will remind you about our place in the sky. A quiet rumble, as if a dark cloud had suddenly passed overhead. Didn’t expect a physics lesson on this beautiful day. 2 The only physics needed, my friend, you learned as a child, so not to worry. The sketch is a top view, looking down on the earth’s north pole. You see the moon in its monthly orbit, moving in the same direction as the earth’s rotation. And while this is going on, the earth and moon together orbit the distant sun once a year, in about twelve months, right? Got it skippah. -

Promoting Change in Common Tern (Sterna Hirundo) Nest Site Selection to Minimize Construction Related Disturbance

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Fish & Wildlife Publications US Fish & Wildlife Service 9-2019 Promoting Change in Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) Nest Site Selection to Minimize Construction Related Disturbance. Peter C. McGowan Jeffery D. Sullivan Carl R. Callahan William Schultz Jennifer L. Wall See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usfwspubs This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Fish & Wildlife Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Fish & Wildlife Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Peter C. McGowan, Jeffery D. Sullivan, Carl R. Callahan, William Schultz, Jennifer L. Wall, and Diann J. Prosser Table 2. The caloric values of seeds from selected Bowler, P.A. and M.E. Elvin. 2003. The vascular plant checklist for the wetland and upland vascular plant species in adjacent University of California Natural Reserve System’s San Joaquin habitats. Freshwater Marsh Reserve. Crossosoma 29:45−66. Clarke, C.B. 1977. Edible and Useful Plants of California. Berkeley, Calories in CA: University of California Press. Calories per Gram of seed 100 Grams Earle, F.R. and Q. Jones. 1962. Analyses of seed samples from 113 Wetland Vascular Plant Species plant families. Economic Botanist 16:221−231. Ambrosia psilolstachya (4.24 calories/g) 424 calories Ensminger, A.H., M.E. Ensminger, J.E. Konlande and J.R.K. Robson. Artemisia douglasiana (3.55 calories/g) 355 calories 1995. The Concise Encyclopedia of Foods and Nutrition. -

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula Antillarum Lesson Other

Common Name: LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula antillarum Lesson Other Commonly Used Names: Little tern, silver turnlet, sea swallow, minute tern, little striker, and killing peter Previously Used Names: Sterna antillarum Family: Laridae Rarity Ranks: G4/S3 State Legal Status: Rare Federal Legal Status: Interior population listed as endangered. Other populations are not federally listed. Federal Wetland Status: N/A Description: Georgia's smallest tern at about 23 cm (9 in) in length with a 50 cm (20 in) wingspread, the least tern is white with pale gray feathers on the back and upper surfaces of the wings, except for a narrow black stripe along the leading edge of the upper wing feathers. The least tern has a black cap with a small patch of white on the forehead. In summer, the adult has a yellow bill with a black tip and yellow to orange feet and legs. Its tail is deeply forked. In winter, the bill, legs and feet are black. The juvenile has a black bill and yellow legs, and the feathers of the back have dark margins, giving the bird a distinctly "scaled" appearance. The least tern's small size, white forehead, and yellow bill serve to distinguish it from other terns. Similar Species: The adult sandwich tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis) is the most similar species to the adult least tern, but is much larger at about 38 cm (15 in) in length and has a black bill with a pale (usually yellow) tip and black legs. Juvenile least terns and sandwich terns look very similar in appearance. -

Forage Fish Management Plan

Oregon Forage Fish Management Plan November 19, 2016 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Resources Program 2040 SE Marine Science Drive Newport, OR 97365 (541) 867-4741 http://www.dfw.state.or.us/MRP/ Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Need ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Federal action to protect Forage Fish (2016)............................................................................................ 7 The Oregon Marine Fisheries Management Plan Framework .................................................................. 7 Relationship to Other State Policies ......................................................................................................... 7 Public Process Developing this Plan .......................................................................................................... 8 How this Document is Organized .............................................................................................................. 8 A. Resource Analysis .................................................................................................................................... -

Sterna Hirundo Linnaeus, 1758

Sterna hirundo Linnaeus, 1758 AphiaID: 137162 COMMON TERN Gnathostomata (Infrafilo) > Tetrapoda (Superclasse) > Laridae (Familia) Jorge Araújo da Silva / Nov. 09 2011 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Mai. 02 2013 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Mai. 04 2013 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Nov. 09 2011 1 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Nov. 09 2011 Facilmente confundível com: Sternula albifrons Chlidonias niger Andorinha-do-mar-anã Gaivina-preta Sterna sandvicensis Garajau-comum Estatuto de Conservação Principais ameaças 2 Sinónimos Gaivina, Garajau (Madeira e Açores) Sterna fluviatilis Naumann, 1839 Referências Sepe, K. 2002. “Sterna hirundo” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed November 30, 2018 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sterna_hirundo/ BirdLife International. 2018. Sterna hirundo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22694623A132562687. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018 2.RLTS.T22694623A132562687.en original description Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decima, reformata. Laurentius Salvius: Holmiae. ii, 824 pp., available online athttps://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.542 [details] additional source Cattrijsse, A.; Vincx, M. (2001). Biodiversity of the benthos and the avifauna of the Belgian coastal waters: summary of data collected between 1970 and 1998. Sustainable Management of the North Sea. Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs: Brussel, Belgium. 48 pp. [details] basis of record van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. -

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

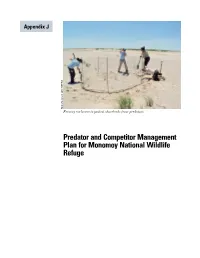

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Dwergstern3.Pdf

99 PRIMARY MOULT, BODY MASS AND MOULT MIGRATION OF LITTLE TERN STERNAALBIFRONS IN NE ITALY GIUSEPPE CHERUBINI, LORENZO SERRA & NICOLA BACCETTI Cherubini G., L. Serra & N. Baccetti 1996. Primary moult, body mass and moult migration of Little Tern Sterna albifrons in NE Italy. Ardea 84: 99 114. Large post-breeding gatherings of Little Terns Sterna albifrons are regu larly observed in the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Here, during five consecutive \ 1/ trapping seasons, 2956 birds were examined and ringed. Their breeding area, as indicated by 163 direct recoveries (mainly juveniles, ringed as chicks), spans over a broad sector of the Adriatic coasts, with colonies lo cated up to 133 km far. During their stay at the study area, adults undergo an almost complete moult. Two partial primary moult cycles can be ob \ served, the first of them being suspended when 2-4 outermost long primar ies have not yet been shed. Pre-migratory body mass build-up, enough for a ~/ flight longer than 1000 km, takes place during the very last days before de parture to the winter quarters, in most cases when the moult has reached a I suspended stage. Active primary moult and body mass increase do overlap in late moulting birds (after 27 August), indicating that the two processes are compatible, in case of time shortage. Post-breeding movements to the Lagoon of Venice seem to fit most requisites of moult migration. Key words: Sterna albifrons - Italy - biometrics - moult migration - ringing - fattening Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca' Fornacetta 9,1-40064 Oz zano Emilia BO, Italy. -

A Changing Nutrient Regime in the Gulf of Maine

ARTICLE IN PRESS Continental Shelf Research 30 (2010) 820–832 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Continental Shelf Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/csr A changing nutrient regime in the Gulf of Maine David W. Townsend Ã, Nathan D. Rebuck, Maura A. Thomas, Lee Karp-Boss, Rachel M. Gettings University of Maine, School of Marine Sciences, 5706 Aubert Hall, Orono, ME 04469-5741, United States article info abstract Article history: Recent oceanographic observations and a retrospective analysis of nutrients and hydrography over the Received 13 July 2009 past five decades have revealed that the principal source of nutrients to the Gulf of Maine, the deep, Received in revised form nutrient-rich continental slope waters that enter at depth through the Northeast Channel, may have 4 January 2010 become less important to the Gulf’s nutrient load. Since the 1970s, the deeper waters in the interior Accepted 27 January 2010 Gulf of Maine (4100 m) have become fresher and cooler, with lower nitrate (NO ) but higher silicate Available online 16 February 2010 3 (Si(OH)4) concentrations. Prior to this decade, nitrate concentrations in the Gulf normally exceeded Keywords: silicate by 4–5 mM, but now silicate and nitrate are nearly equal. These changes only partially Nutrients correspond with that expected from deep slope water fluxes correlated with the North Atlantic Gulf of Maine Oscillation, and are opposite to patterns in freshwater discharges from the major rivers in the region. Decadal changes We suggest that accelerated melting in the Arctic and concomitant freshening of the Labrador Sea in Arctic melting Slope waters recent decades have likely increased the equatorward baroclinic transport of the inner limb of the Labrador Current that flows over the broad continental shelf from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland to the Gulf of Maine. -

Fastest Migration Highest

GO!” Everyone knows birds can fly. ET’S But not everyone knows that “L certain birds are really, really good at it. Meet a few of these champions of the skies. Flying Acby Ellen eLambeth; art sby Dave Clegg! Highest You don’t have to be a lightweight to fly high. Just look at a Ruppell’s griffon vulture (left). One was recorded flying at an altitude of 36,000 feet. That’s as high as passenger planes fly! In fact, it’s so high that you would pass out from lack of oxygen if you weren’t inside a plane. How does the vulture manage? It has Fastest (on the level) Swifts are birds that have that name for good special blood cells that make a small amount reason: They’re speedy! The swiftest bird using its own of oxygen go a long way. flapping-wing power is the common swift of Europe, Asia, and Africa (below). It’s been clocked at nearly 70 miles per hour. That’s the speed limit for cars on some highways. Vroom-vroom! Fastest (in a dive) Fastest Migration With gravity helping out, a bird can pick up extra speed. Imagine taking a trip of about 4,200 And no bird can go faster than a peregrine falcon in a dive miles. Sure, you could easily do it in an airplane. after prey (right). In fact, no other animal on Earth can go as But a great snipe (right) did it on the wing in just fast as a peregrine: more than 200 miles per hour! three and a half days! That means it averaged about 60 miles The prey, by the way, is usually another bird, per hour during its migration between northern which the peregrine strikes in mid-air with its balled-up Europe and central Africa. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour.