Convention on Migratory Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish Leather, Anyone?

Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Aquaculture Department SEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository http://repository.seafdec.org.ph Journals/Magazines Aqua Farm News 1995 Fish leather, anyone? Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center, Aquaculture Department (1995). Fish leather, anyone? Aqua Farm News, 13(1), 16-17, 18. http://hdl.handle.net/10862/2458 Downloaded from http://repository.seafdec.org.ph, SEAFDEC/AQD's Institutional Repository Fish leather, anyone? SHARK LEATHER a) the existing leather tannery infrastruc Previously regarded as a by-catch of lim ture is well-developed especially around Ma ited potential, shark is now targetted by small- dras; scale fishermen in the Bay of Bengal for leather b) operating costs are relatively low; and production. c) offshore resources of sharks are not Fish, let alone shark, does not conjure up sufficiently tapped at present. images of leather goods unlike cow, goat or An environmentally significant point is that crocodile. shark and fish leathers in general are essentially The method of obtaining the raw material food industry by-products which would otherwise and the specialized nature of the market hamper be wasted. Other exotic leathers produced from success in this field and general awareness of crocodile and snake, for example, have negative potential. connotations in this respect in spite of their Shark is a hunted resource often captured increased production through culture. by small-scale fishermen only as by-catch, and primarily landed for its meat. It may therefore be Offshore resources difficult to obtain a regular supply of raw material The offshore zone is the realm of the large for what is a totally different industry. -

Traceability Study in Shark Products

Traceability study in shark products Dr Heiner Lehr (Photo: © Francisco Blaha, 2015) Report commissioned by the CITES Secretariat This publication was funded by the European Union, through the CITES capacity-building project on aquatic species Contents 1 Summary.................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Structure of the remaining document ............................................................................. 9 1.2 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... 10 2 The market chain ................................................................................................................... 11 2.1 Shark Products ............................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Shark fins ............................................................................................................... 12 2.1.2 Shark meat ............................................................................................................. 12 2.1.3 Shark liver oil ......................................................................................................... 13 2.1.4 Shark cartilage ....................................................................................................... 13 2.1.5 Shark skin .............................................................................................................. -

Re-Examining the Shark Trade As a Tool for Conservation

Re-examining the shark trade as a tool for conservation Shelley Clarke1 Shark encounters of the comestible Therefore, while sharks have become conspicuous as entertainment since the 1970s, they have been impor- kind tant as commodities for centuries. Telling the tale of public fascination with sharks usually begins with the blockbuster release of the movie “Jaws” In September 2014, the implementation of multiple in the summer of 1975. This event more than any other new listings for sharks and rays by the Convention on is credited with sparking a demonization of sharks that International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of has continued for decades (Eilperin 2011). In recent Wild Fauna and Flora (Box 1), underscored the need to years, less deadly but equally adrenalin-charged shark re-kindle interest in using trade information to comple- interactions, including cage diving, hand-feeding and ment fisheries monitoring. These CITES listings are a even shark riding, have captured the public’s attention spur to integrate international trade information with through ecotourism, television and social media. These fishery management mechanisms in order to better reg- more positive encounters (at least for most humans), in ulate shark harvests and to anticipate future pressures combination with many high-profile shark conservation and threats. To highlight both the importance and com- campaigns, have turned large numbers from shark hat- plexity of this integration, this article will explore four ers to shark lovers, and mobilized political support for common suppositions about the relationship between shark protection around the world. shark fishing and trade and point to areas where further work is necessary. -

Mercury Info Sheet

Methyl Mercury The danger from the sea Report by SHARKPROJECT International • Aug. 31, 2008 Updated by Shark Safe Network Sept. 12, 2009 ! SHARK MEAT CONTAINS HIGH LEVELS OF METHYL MERCURY: A DANGEROUS NEUROTOXIN In the marine ecosystem sharks are on top of the food chain. Sharks eat other contaminated fish and accumulate all of the toxins that they’ve absorbed or ingested during their lifetimes. Since mercury is a persistent toxin, the levels keep building at every increasing concentrations on the way up the food chain. For this reason sharks can have levels of mercury in their bodies that are 10,000 times higher than their surrounding environment. Many predatory species seem to manage high doses of toxic substances quite well. This is not the case, however, with humans on whom heavy metal contamination takes a large toll. Sharks at the top end of the marine food chain are the final depots of all the poisons of the seas. And Methyl Mercury is one of the biologically most active and most dangerous poisons to humans. Numerous scientific publications have implicated methyl mercury as a highly dangerous poison. Warnings from health organizations to children and pregnant women to refrain from eating shark and other large predatory fish, however, have simply not been sufficient, since this “toxic food-information” is rarely provided at the point of purchase. Which Fish Have the Highest Levels of Methyl Mercury? Predatory fish with the highest levels of Methyl Mercury include Shark, King Mackerel, Tilefish and Swordfish. Be aware that shark is sold under various other names, such as Flake, Rock Salmon, Cream Horn, Smoked Fish Strips, Dried cod/stockfish, Pearl Fillets, Lemonfish, Verdesca (Blue Shark), Smeriglio (Porbeagle Shark), Palombo (Smoothound), Spinarolo (Spiny Dogfish), and as an ingredient of Fish & Chips or imitation crab meat. -

THE SHARK and RAY MEAT NETWORK a DEEP DIVE INTO a GLOBAL AFFAIR 2021 Editor Evan Jeffries (Swim2birds)

THE SHARK AND RAY MEAT NETWORK A DEEP DIVE INTO A GLOBAL AFFAIR 2021 Editor Evan Jeffries (Swim2birds) Communications Stefania Campogianni (WWF MMI), Magdalena Nieduzak (WWF-Int) Layout Bianco Tangerine Authors Simone Niedermüller (WWF MMI), Gill Ainsworth (University of Santiago de Compostela), Silvia de Juan (Institute of Marine Sciences ICM (CSIC)), Raul Garcia (WWF Spain), Andrés Ospina-Alvarez (Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies IMEDEA (UIB- CSIC)), Pablo Pita (University of Santiago de Compostela), Sebastián Villasante (University of Santiago de Compostela) Acknowledgements Serena Adam (WWF-Malaysia), Amierah Amer (WWF-Malaysia), Monica Barone, Andy Cornish (WWF-Int), Marco Costantini (WWF MMI), Chitra Devi (WWF-Malaysia), Giuseppe di Carlo (WWF MMI), Caio Faro (WWF Brazil), Chester Gan (WWF-Singapore), Ioannis Giovos (iSea), Pablo Guerrero (WWF-Ecuador), Théa Jacob (WWF-France), Shaleyla Kelez (WWF-Peru), Patrik Krstinić (WWF-Adria), Giulia Prato (WWF-Italy), Rita Sayoun (WWF-France), Umair Shahid (WWF-Pakistan), Vilisoni Tarabe (WWF-Pacific), Jose Luis Varas (WWF-Spain), Eduardo Videira (WWF-Mozambique), Ranny R. Yuneni (WWF-Indonesia), Heike Zidowitz (WWF-Germany). Special acknowledgments to contribution of Glenn Sant (TRAFFIC). Special acknowledgements go to WWF-Spain for funding the scientific part of this report. For contact details and further information, please visit our website at wwfmmi.org Cover photo: © Monica Barone / WWF Safesharks Back cover photo: © Matthieu Lapinski / Ailerons WWF 2021 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 SHARKS AND RAYS IN CRISIS 6 THE OVERALL TRADE VALUE 7 GLOBAL NETWORK ANALYSIS 8 SHARK MEAT TRADE 10 RAY MEAT TRADE 18 THE ROLE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION IN THE SHARK AND RAY TRADE 26 A GLOBAL SELECTION OF DISHES WITH SHARK AND RAY MEAT 28 RECOMMENDATIONS 30 © Nuno Queirós (APECE) / WWF 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SHARKS AND RAYS ARE IN CRISIS GLOBALLY Up to 100 million are killed each year, and some populations have declined by more than 95% as a result of overfishing. -

Caracterización Del Riesgo Por Exposición a Metilmercurio Por Consumo No Intencional De Carne De Tiburón En Mujeres De México

MONOGRÁFICO 167 Caracterización del riesgo por exposición a metilmercurio por consumo no intencional de carne de tiburón en mujeres de México Caracterização do risco de exposição à metilmercurio do consumo não intencional de carne de tubarão em mulheres do México Characterization of the Risk of Exposure to Methylmercury Due to the Non- intentional Consumption of Shark Meat by Mexican Women Laura Elizalde-Ramírez, Patricia Ramírez-Romero, Guadalupe Reyes-Victoria, Edson Missael Flores-García Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Iztapalapa, México. Cita: Elizalde-Ramírez L, Ramírez-Romero P, Reyes-Victoria G, Flores-García EM. Risk characterization of exposure to methylmercury due to non-intentional consumption of shark meat in females from Mexico. Rev. salud ambient. 2020; 20(2):167-178. Recibido: 27 de mayo de 2020. Aceptado: 10 de noviembre de 2020. Publicado: 15 de diciembre de 2020. Autor para correspondencia: Patricia Ramírez-Romero. Correo e: [email protected] Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, México. Financiación: Proyecto “Indicadores de integridad ecológica y salud ambiental”, de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana de México, programa de posgrado en Energía y Medio Ambiente (PEMA) y el Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT, México) a través del M. Sc. Beca No. 659582. Declaración de conflicto de intereses: Los autores declaran que no existen conflictos de intereses que hayan influido en la realización y la preparación de este trabajo. Declaraciones de autoría: Todos los autores contribuyeron al diseño del estudio y la redacción del artículo. Asimismo todos los autores aprobaron la versión final. Abstract Concern about the health risks due to the consumption of shark meat arose in two previous studies in which shark meat with high concentrations of methylmercury (MeHg) and fish meat with up to 60 % substitution with shark meat were documented. -

Part 4. on Histamine in Shark Meat

Title STUDIES ON SHARK MUSCLE:PART 4. ON HISTAMINE IN SHARK MEAT Author(s) OHOISHI, Keiichi Citation 北海道大學水産學部研究彙報, 4(2), 119-122 Issue Date 1953-08 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/22801 Type bulletin (article) File Information 4(2)_P119-122.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP STUDIES ON SHARK MUSCLE PART 4. ON HISTAMINE IN SHARK MEAT Keiichi OHOISHl (Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University) Introduction Cases of poisoning by fish meat have been frequently reported the cause of which may be considered to be ptomaine, especially some amines. Actually several amines have been separated from putrefactive meat'P. Histamine is or.e of those amines; it is seriously toxic. On.e cause of the saying "mackerel stinks alive" may be the rapid decomposition of the meat; in the decomposed mackerel, meat the formation of histamine is used to recognized. The mechanism of the histamine formation in mackerel meat may be explained as follows: (1) Fresh fish meat indicates acidic reaction. (2) The decomposition of amino acids by bacteria in acidic medium is dominant in de carboxylation, so the amines corresponding to those amino acids are obtained'!). (3) A large amount of histidine is contained in the extractive matter of mackerel meat in comparison with other fish having white meat'S) . In accordance with the above three items, the mackerel meat, looking rather quite fresh, may contain a large amount of histamine, of which the quantity is enough to cause poison ing. The other hand. it has been already said that shark meat having a large amount of ammonia shows several features of good freshness except for developing ammonia(4). -

Sharks Score Well in Texas Taste Surveys Texas Calls Black Drum

tember. The course of study will last 3 6·month agreement was signed on 1 On the attitude survey, individuals to 5 years. June 1976. were asked their reaction if they ate a Albania has extended its territorial The Scottish Highlands and Develop piece of good-tasting fish and were sea to 15 nautical miles from 12 miles, a ment Board is funding a $750,000 study then told it was shark meat. Out of 199 distance it has claimed since 1970. on the blue whiting stocks of the respondents, 144 , or 72 percent, said Iceland's general strike and the Western Isles to determine if stocks they would be pleasantly surprised and trawlermen's strike ended on 28 can support a fish meal industry. continue eating. Only 23 persons, 11 February. Meanwhile, there was pro Preliminary tests indicate that 500,000 percent, said they would be upset at gress in the fisheries dispute between . metric tons of blue whiting could be being told it was shark meat and stop Iceland and the United Kingdom and a caught each season. eating. "Our data thus far indicate shark is Fishery Notes not all that different in taste from other types of fish and what differences there Sharks Score Well in Texas Taste Surveys are are in the shark's favor. Its meat is Shark meat fared well when com highest, 4.5, while the small treated of firmer texture, and won't flake pared with accepted seafoods like piece was rated lowest at 3.5. apart, 65 percent of the animal is edible redfish, according to a shark meat For the third test, the shark meat and there are no bones in the flesh," taste test and attitude survey con was breaded and fried. -

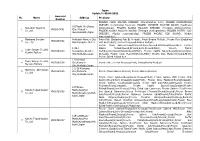

Japan Update to 05.04.2021 Approval No Name Address Products Number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus Keta)

Japan Update to 05.04.2021 Approval No Name Address Products Number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus keta). FROZEN DOLPHINFISH DRESSED (Coryphaena hippurus). FROZEN JAPANESE SARDINE ROUND (Sardinops 81,Misaki-Cho,Rausu- Kaneshin Tsuyama melanostictus). FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK DRESSED (Theragra chalcogramma). 1 VN01870001 Cho, Menashi- Co.,Ltd FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK ROUND (Theragra chalcogramma). FROZEN PACIFIC COD Gun,Hokkaido,Japan DRESSED. (Gadus macrocephalus). FROZEN PACIFIC COD ROUND. (Gadus macrocephalus) Maekawa Shouten Hokkaido Nemuro City Fresh Fish (Excluding Fish By-Product); Fresh Bivalve Mollusk.; Frozen Fish (Excluding 2 VN01860002 Co., Ltd Nishihamacho 10-177 Fish By-Product); Frozen Processed Bivalve Mollusk; Frozen Chum Salmon(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet,Head,Bone,Skin); Frozen 1-35-1 Alaska Pollack(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Pacific Taiyo Sangyo Co.,Ltd. 3 VN01840003 Showachuo,Kushiro- Cod(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Pacific Saury(Round,Dressed,Semi- Kushiro Factory City,Hokkaido,Japan Dressed); Frozen Chub Mackerel(Round,Fillet); Frozen Blue Mackerel(Round,Fillet); Frozen Salted Pollack Roe 3-9 Komaba- Taiyo Sangyo Co.,Ltd. 4 VN01860004 Cho,Nemuro- Frozen Fish ; Frozen Processed Fish; (Excluding By-Product) Nemuro Factory City,Hokkaido,Japan 3-2-20 Kitahama- Marutoku Abe Suisan 5 VN01920005 Cho,Monbetu- Frozen Chum Salmon Dressed; Frozen Salmon Dressed Co.,Ltd City,Hokkaido,Japan Frozen Chum Salmon(Round,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Salmon Milt; Frozen Pink Salmon(Round,Semi-Dressed,Dressed,Fillet); -

IDENTIFICATION of SHARK and RAY in LOCAL SEAFOOD RESTAURANTS in WEST JAVA, INDONESIA Rega Permana*, Aulia Andhikawati

GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 8, August 2021 ISSN 2320-9186 338 GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 8, August 2021, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com IDENTIFICATION OF SHARK AND RAY IN LOCAL SEAFOOD RESTAURANTS IN WEST JAVA, INDONESIA Rega Permana*, Aulia Andhikawati Fisheries Department, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia *Corresponding email: [email protected] KeyWords Grilled Shark, Extreme Seafood, Culinary Protected Species, Shark, Ray, Bandung, Indramayu ABSTRACT In various regions in Indonesia, especially Bandung and Indramayu, there are still several restaurants that sell dishes of several species that are classified as considered, vulnerable to almost threatened according to IUCN. Among these species are sharks, rays, and green sand lob- sters. With the ethnic homogeneity of Indonesia, there are many simple reasons for cultural beliefs to consume these species. The price offered is quite varied depending on how it is prepared and the type, for example shark dishes that are sold at the Pantura Seafood restau- rant for Rp. 11,000 / ounce. The high supply and demand in the country and abroad has led to rampant fishing of these species. thus posing a major threat to the preservation of these species in nature. There are several methods to overcome these problems including socialization and education to the public and culinary entrepreneurs so that they are aware that the condition of protected species must be maintained. INTRODUCTION Indonesia is an archipelagic country that is rich in ethnic and national diversity, where there are various types of diversity that ad- here to norms according to their respective regions. -

Part 3: Maritime World and Multi-Sited Ethnography Introduction

The Journal of Sophia Asian St udies No.33 (201 5) Part 3: Maritime World and Multi-sited Ethnography M ono-kenkyu and a Multi-sited Approach: Toward a Wise and Sustainable Use of Shark Resources at Kesennuma orthern Japan* AKAMI Jun** Introduction Traditional cioeconomic history focused mainly on major agriculLUral pr du t , . uch a. collon, indigo, tobacco . ugar rice and n, namely tho ·e utilized for trade in 1he i111emational commodity market. The late Profc sor Murai Yo hinori however i one of lhe f w socioeconomic hi torian. , ho was interested in marine product such as hrimps. hark fin ·. pearls. tonoi h lls. sea cucumber etc .. and b side·, h displayed keen imere t in things that may appear trivial with regard Lo the national economy. bul yet arc vital commoditie. for outh a t ian people. a. for example second hand clothe and charcoal made from mangrove trees. ome of the item that Murai had an intere l in have a long hi tory of trade. whether between i land or acros national boundarie . After th' nation state , ere e tabli hcd at the clo ·c of World War II. those trade were declared illegal. and were viewed a f rm. of muggling. Hence. there is no explicit data available in the national tati tic ·. on tho e animated undertaking ·. Thereafter Murai conductcc.l fieldwork within the eastern i. land!- of lndonc. ia in que. t of tho c trades . whereby he described the * Earlier ver ions of 1hi. anicle were presented on 1wo differcnl occasion,. -

) United States Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

United states Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Fishery Leaflet 30 C:~1oago 54, Ill. Revised April 1946 PR~AHATION OF THR~ Jt'IS"n--';;:S OF TIP. PACI~TIC COAST Shark, Shad, and Lingcod Prepared in the Division of COl'1mercial Fisheries Our Pacific coast ·Naters teem with a score of fishes regularly sought and sold for table use: white sea bass, sh8.d, halibut, sallnon, ~.mel t I sablefish, rockfish, sole, lingcod, an.d more recPIltly, shark. These and ma:'1V others are available fresh practico.lly the year-round in most coastal markets, and are pre pared in many ways. In this le8.flet recipes arA given for cooking three of th~s e speCies: shark, shad, and the so-called lingcod. ) SHARK Properly prepa.red for the tabl") , shark meat tastes very much like that of otller popular food fishes. Its cooked meat is fir.m, a'1d rattter Suef;ests that of t:iP. swordfish in texture. The soupfin shark, the one most important tc t118 consumer bec8usI? of thl') high vi ta."!lin A content of its Ii vel' oil as well as the food value. of its flesh, ranges up to 5 and 6 feet in length and from 25 to 40 pounds in ',;ei!;ht. [i'illets or transverse sections a re cut ~\1hich are later reduced to con.veni ent steaks or . cutlets. for market. ;'lhen cooked, the broad, darY~ band under th0 s::in along each side of the shark turns white. A popular way to serve the fillets is to bake them in S-pani,':;L saUCA.